- Culture

- 05 Aug 22

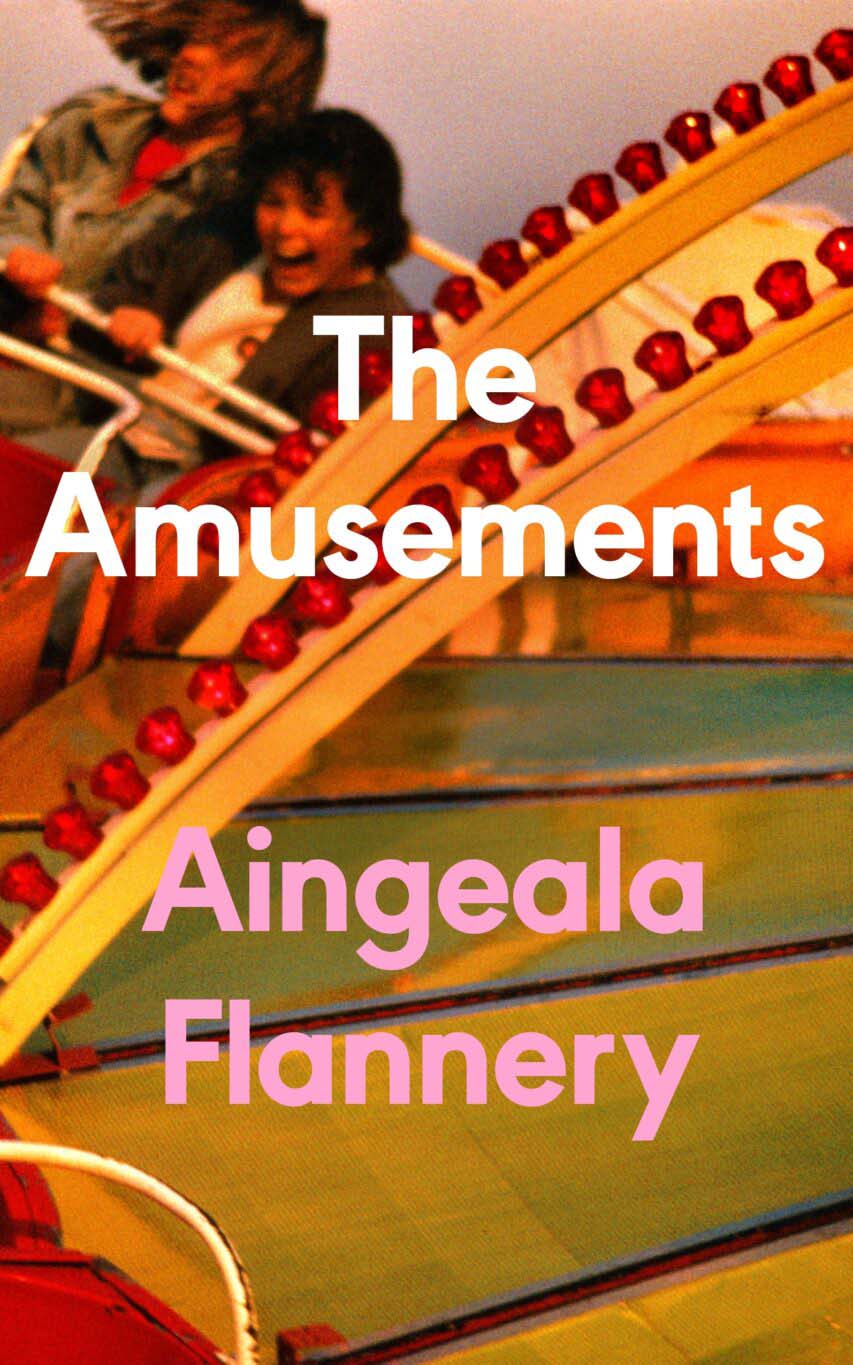

Aingeala Flannery: "Maybe that’s why The Amusements took three years to write - I just didn’t want to leave them"

Award-winning journalist and short story writer Aingeala Flannery adds ‘novelist’ to her repertoire with her debut book, The Amusements. She talks about treating her characters with tenderness, and drawing inspiration from the seaside town of Tramore.

There’s something mystical about all the places we aren’t from. Dublin-based author Aingeala Flannery revels in being an outsider, bringing vivid life to a forgotten coastal community in her debut novel, The Amusements.

What local teen and aspiring artist Helen Grant knows of the world comes from Tramore and the axis it seems to spin on. To Helen, Stella Swain, her reckless, manic-pixie-dream-girl of a best friend, is everything. Which is to say – Helen doesn’t know much.

Through an unconventional structure, each chapter holds an observational looking glass to the lives of various locals and a few temporary visitors, returning over the course of decades to Helen and Stella, their families and the transparent ties between the people of Tramore.

“Maybe that’s why it took three years to write,” ponders Flannery. “Because I just didn’t want to leave them. I grew so attached to all of them.”

Born in Waterford but raised in Dublin, Flannery eventually graduated from University College Dublin with an MFA in Creative Writing. It was upon her father’s death when her mother decided to return to her Waterford roots.

“The place that made her happiest,” Flannery says, “was Tramore. I’m an outsider, I’m not from there, but I do have a bit of insider knowledge.”

Aingeala Flannery. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Aingeala Flannery. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Setting aside the unfinished novel she had been working on at the time, Flannery recalls, “I thought I would try and write a short story about Tramore.” Along came ‘The Court Order,’ which went on to be published in the Bath Anthology. Then came the short story ‘Visiting Hours’, which depicts Helen Grant as a young girl visiting her alcoholic father in hospital.

“I loved writing that, but when I went back to the novel I couldn’t get Helen out of my head,” says Flannery. “I was constantly thinking about what happened to her. That family were under my skin. I don’t think I’m alone in loving seaside towns. They offer you so much and they’re so full of raw material for writers. During the ‘70s and ‘80s when Ireland was in a terrible economic depression, Tramore did go downhill.”

Knowing what the town once was provided context to some of Flannery’s more grim descriptions: litter is often streamed along the coastline; dilapidated hotels barely manage to stand; and there’s a sense of neglect from local authorities.

“Economic depression and unemployment are not character defects,” Flannery makes clear. “That’s somebody’s responsibility and it’s not that of the people in the town, but of the authorities in charge.”

Still, that’s not a weight Flannery feels the need to carry.

“I wouldn’t say that I feel a responsibility toward the town,” she explains, as it isn’t her job. She’s not a travel writer, after all. “I wouldn’t want people to read the book and think, ‘Oh god, Tramore is an awful kip.’ Because it isn’t. It has a huge history.”

For every patch of love in The Amusements, there is equal hate.

“I wanted to keep going with the characters who are flawed, whom I love,” says Flannery, “who are given chances to redeem themselves and who don’t always take it. I wanted the reader to find out where that took them. I needed a catharsis.”

The process of release is something each character faces in one way or another. For Helen and Stella, it looks like deciding what – and who – to leave in Tramore, when departure becomes a choice.

“When you go back to where you’re from, you go back to childhood,” says Aingeala. “People go back to those roles they had when they were children, and it brings up parts of themselves that they’ve left behind in their adult lives and don’t want to necessarily revisit.”

As for the affection Helen feels for Stella as a teenager, Flannery says, “I think that most teenage girls fall in love with their best friends at some point. That’s a very intense kind of relationship. Helen’s not really exploring her sexuality, she just loves this person, and she loves life and the idea of a better future, and that’s what Stella represents. When you’re a teenager, you just want out. You want to break away and it is natural.”

The knot that keeps the people of Tramore tied together is a cause of strangulation at times. At others, it’s the one thing keeping them from falling apart.

“I think that’s true of any small town, the people who come from small towns have a love-hate relationship with it,” Flannery explains. “There’s so much that’s attractive and there’s that sense of community, of family and your personal history tied up with it. But that can also be suffocating. It’s that constant conflict between what nurtures and what suffocates.”

The cast of characters Flannery has come up with is a compelling one.

“They’re just like imaginary friends,” she elaborates. “You’re walking around and instead of obsessing over your own family and friends, you’ve got this fictional family down in Tramore. They became people in my mind. I was going up and down to Tramore… I was going to visit these characters that didn’t exist outside of my head!”

Flannery shares the people in her mind with us, handling them with a sympathetic kind of care. She gives us a caravan park manager, the owner of a bed and breakfast. a callous mother, and a cheating husband on vacation with his family. Through the people who leave and the people who stay, Tramore itself becomes a dynamic character.

And, like anything compelling, you’re left to wonder if you hate it or if it might just be the most magical place in the world.

• The Amusements is out now, published by Sandycove.

Read more interviews and music news in our brand new issue, out now.

RELATED

- Culture

- 01 Jul 22

Book Review: Aingeala Flannery - The Amusements

- Culture

- 28 Dec 25

My 2025: Lou Robbie - Hero of 2025? "Most definitely Catherine Connolly"

- Culture

- 26 Dec 25