- Culture

- 23 Apr 24

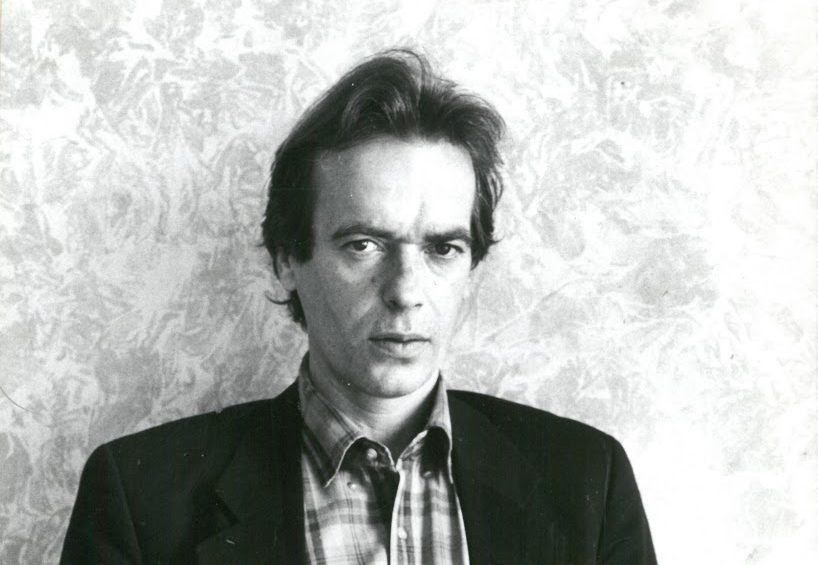

The latest novel from Scottish author Andrew O’Hagan, Caledonian Road, explores the culture wars against the panoramic backdrop of modern London. He talks class, Martin Amis, Joyce, Julian Assange, Irvine Welsh and more.

Caledonian Road, the latest novel from 55-year-old Scottish author Andrew O’Hagan, is an epic affair which has at its centre the affluent, middle-aged London academic Campbell Flynn. There is a growing sense in cultural circles that Flynn and his type are yesterday’s men, and indeed when we meet him, he has just published, anonymously, an essay about the crisis in contemporary masculinity.

Simultaneously, Flynn – also an author who writes books about the great Dutch painters – befriends one of his students, Milo Mangasha, who’s also a computer hacker and radical post-colonial theorist. While Flynn thinks the friendship is on solid footing, Milo sees in the older lecturer the opportunity for a show-trial.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg in a novel that looks at modern London with Dickensian scope, with the narrative variously encompassing bankers, Russian oligarchs, Saudi property magnates, drill artists, bitcoin investors, drug dealers and more. Still, in its study of Campbell Flynn, Caledonian Road – like Todd Field’s Oscar-nominated Tar from last year – fascinatingly explores how the culture wars are playing out in academia.

Like Lydia Tar, Flynn is an archetypal Gen X-er who believes anything goes in art, which brings him into conflict with a younger generation.

“I think that’s the problem for him actually, you’ve put your finger on it,” says the friendly O’Hagan, speaking from his London home. “He’s a Gen X man who takes those liberties for granted. He’s a working class guy from Glasgow who’s become this kind of cultural force in a bigger place. He feels he’s a natural in that world of knowing things, and that’s where he comes a cropper, because this book shows how a generational clash is possible nowadays.

Advertisement

“No matter how on the left he is, or how many marches he went on, or how much he believes in his queer daughter, to a younger generation, he might be part of the problem. That for me is drama – it’s what a big novel can do. I don’t have an editorial position on these issues, because I don’t believe I have to. I resist this idea that novelists must be editorialists – that novelists these days have to be activists.

“I like novelists when they live in the centre of an ambivalence. They don’t sell certainty to their readers; they offer up a whole set of contradictions, and the readers will decide what is and isn’t for them.”

Certainly, the conflict over art is one of the major themes in the culture right now.

“That’s why I did it,” nods O’Hagan. “It’s probably the most contemporary book I’ve ever written in that way. It’s positioned right at the centre of a huge, almost Dickensian-sized problem about, ‘How do we live? Are we any good?’ Even if we think we’re on the right side of history, and supported all the right causes, are we part of the problem? And is there a generation that’s too ready to tell us we are?

“On both sides, there’s the potential for failure. I wanted this novel to be an entertaining stress test about what we’re like with each other now. The novels I grew up with were like that.”

From a working class Glasgow background, O’Hagan started his career at the London Review Of Books – where he is now editor-at-large – before going on to become an author, whilst occasionally lecturing at King’s College in London. Class has become a major factor in cultural disputes, with people from a working class background often in conflict with those who’ve been privately educated or attended elite universities.

Advertisement

“It is a madness at a moment,” acknowledges Andrew. “Someone once brilliantly referred to ‘the narcissism of small differences’. We’re living through a period that’s really invested in that. It’s almost a resistance to facing the biggest problem politically, which is class – it’s about engrained prejudices. Because even when you enter into the area of race, there are many upper class people who went to public school who, whether they’re white or non-white, I would still have an argument with on the basis of class.

“It’s about the deployment of public schools and private education as a way of separating people. That isn’t fundamentally a question that’s being addressed, because we’re so caught up in the narcissism of small differences, as if we didn’t breath the same air, take the same public transport, or have red blood inside us. We’re so taken up with what’s almost the fashion of small differences, a kind of overeagerness to find ourselves slave-drivers, or call ourselves out for the behaviour of our ancestors.

“All of which I think can be quite a healthy thing in any society, but which often misses the bigger issue – and the pandemic showed us the biggest issue in our society is the ongoing unfairnesses attached to class. If you were working class in Ireland or the UK during the pandemic, the likelihood of you going into an ICU was dramatically higher. And that was exacerbated if you were a person of colour. To be working class and a person of colour was to be vulnerable in a way that upper class people were not.”

In the panoramic view it offers of the English capital, Caledonian Road reminded me of Martin Amis’s 1989 masterpiece, London Fields.

Martin Amis

Martin Amis“It’s funny you should have brought that novel up today,” says Andrew. “Martin Amis’s widow, his estate and Vintage Books just called me yesterday, and asked me if I’d write the introduction to their new Classics edition of Money. I said yes right away. He was a wonderful, deeply satirical writer – I think Martin gave us all a deeper laugh. We laughed deeper because of the things he observed and the sentences he wrote. You saying that – I mean, London Fields is a classic. I really wanted that kind of energy in Caledonian Road.”

Advertisement

A further parallel with London Fields is that Caledonian Road seems to some extent to draw on Ulysses, thanks to its Joycean exploration of consciousness and urban life.

“I think anybody who takes on a city, Joyce is in the back of their mind somewhere,” says O’Hagan. “It’s a ludicrous thing to have in your mind if you hope to progress, but nevertheless, there it is. Joyce’s famous comment was that if Dublin was to be destroyed, his hope was that it could be rebuilt from the pages of his novel. That lives with you, because it gives you a snapshot of his ambition, but also of his sense of the power of literature to record, and make permanent, things which melt into air.

“Cities melt into air – buildings, people, trees, trams. But at their best, literature and art don’t. There’s something deathless in Ulysses that will be there reminding us of Swenys Chemist, next to Trinity College, where Bloom buys that lemon soap. To this day, when I walk up that road next to Trinity, I think of the pages of that book. Ulysses has us in its grip now, in such a permanent way, that we sort of map ourselves onto the city via the book. I find that to be such a huge inspiration.”

Away from fiction, O’Hagan has had an equally fascinating career, with one of his most notable roles being that of ghost-writer of Julian Assange’s autobiography.

“I think where Julian is now is a very different place from where we expected him to be when I first met him,” says O’Hagan. “I admired the project to try and speak truth to power, and to try and hold governments – and especially militaries – to account. He’s travelled into another world now. But I still believe it would be an absolute mistake to punish him for doing the work of telling the truth.

“It’s an amazing situation to contemplate that he’s there facing extradition to America, for doing the work of a journalist, telling the truth. Not for libelling somebody, corruption or getting things wrong, but for the opposite – for getting things right. Given that we do believe in press freedom, and freedom of information, I think they’ll only be making a martyr of Julian Assange if they drag him off to America and imprison him, for doing the work that all of us as writers and journalists would consider to be in the public interest.”

Finally given that I’m a big fan of Irvine Welsh, Iain Banks and Ian Rankin – all peers of O’Hagan’s – I wonder what he makes of that generation of Scottish writers?

Advertisement

“The lovely thing about the generation that you’re talking about and part of, is that we’re quite close,” he says. “Irvine’s been a friend of mine for 25 years, and then you have people like Alan Warner and Janice Galloway. There’s just a great group of us who’ve grown up together as writers. There may be differences in style, approach or subject matter, but there’s an absolute – almost old-fashioned, trade union – faith in the value of the enterprise, and in sticking up for each other.

“That might sound like a no-brainer, but there are loads of literary cultures where that is not true – the opposite is true. There’s rivalry, dislike, mistrust. That’s not the case at all with us. I’ve spent a lot of time socially and professionally with Irvine Welsh and friends like John Niven. There’s actually a really broad group coming about now, where we kind of look out for each other.”

O’Hagan notes their stylistic similarities.

“We’re trying very often to bring onto the page parts of life which haven’t been on the page before,” he says. “Before I wrote Mayflies, there’d been books about female friendships, and some books about rock music, but there had never been that book about a group of working class boys, who were absolutely cemented together by their love of New Order, The Fall and the right bands from that period – the right bands as they saw it!

“Getting that between covers felt like a huge challenge, and a new thing for writing, because it hadn’t been there before. I would love to have read that book, because I was that kid.”

- Caledonian Road is out now.