- Opinion

- 08 May 20

Across the globe, poverty, persecution, violence and war too often form the harsh reality of daily life. As a human rights activist working amongst refugee communities and those surviving oppression, Caoimhe Butterly has seen the devastation caused by wars first hand. As the Covid-19 pandemic continues, she reflects on life, grief and being present in a moment of change.

Breathe in, hold, release.

Seven years ago, less than a quarter mile from land, a ship sank off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa. Amongst the women, men and children on board was a young, pregnant Eritrean student. She, along with 300 other refuge-seekers from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan drowned as the ship went down.

In the days that followed, search and recovery divers found her body amongst those trapped in the hold of the vessel. As they surfaced, her body tied by rope to others recovered, they discovered that she had given birth as the ship went down – her full-term infant, still attached to her, beneath her clothes.

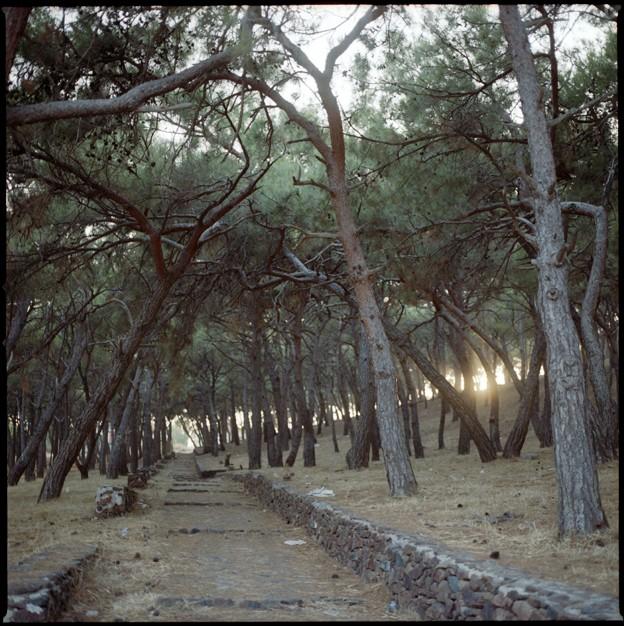

Last August we sat at the port of the same island with survivors of another journey. Those with us had just disembarked an NGO Search and Rescue ship, after weeks at sea, during which they were prevented from disembarkation by mainland authorities. The picturesque bay in front of us, cerulean sea surrounded by sun-bleached cliffs, was shadowed by visceral descriptions of their suffering.

Hawa, an Eritrean seamstress raised in Sudanese refugee camps, spoke of her time in Libyan detention centres, of sexual violence, torture, hunger and daily humiliations.

Advertisement

As we listened, an islander who had passed us, stopped and walked back down the otherwise deserted slip-way towards the group. As he approached, Hawa paused, apprehensively.

The man, a fisherman, knelt down beside us and took off his baseball cap, passing it from one hand to another as he spoke. He had been one of those who had responded to the 2013 ship sinking, alerted by the muffled cries of those on board. He had managed to lift seven survivors into his boat, performing CPR on some of them, alone, on the floor of his small fishing vessel.

He described trying to breathe his breath into them, his panic constricting his throat at times, as he watched those still in the water disappear from view, others floating beyond his boat.

He wanted, he said, to tell the group that he had tried his best, that the memory of those who remained in the sea, of those he couldn’t save, visited him regularly in his dreams. He had lobbied the local municipality to build a monument in the main street of the island, with the names of the dead. He wanted people to pause, to remember, to understand that the sea gave the island life, but that, in these years, it had brought it so much death, too.

He apologised that he hadn’t succeeded in making the monument happen and got up to leave.

Hawa, who had been silent throughout, watching his weathered face and hands, turned to me and asked me to translate. “Tell him,” she said “we see his suffering. We understand his pain”.

Advertisement

A LIFE GRIEVED

Ten years earlier in the back of an ambulance hurtling through the streets of Gaza, it’s siren redundant in an empty city under siege, another type of pain. On the stretcher between us – two paramedics and a volunteer First Responder – a young man with terrible head wounds, sustained when the building his and other families were sheltering in was bombed.

The paramedic opposite, Jamaal, holding a defibrillator whose batteries were dead, made eye contact with me, his face expressing a defeat rarely glimpsed in him, or amongst his colleagues: a cohort of health-workers under-resourced and often targeted, but consistently, often incomprehensibly resilient.

We murmured words of life and care to the unconscious teenager, tried to ease his pain, and then became momentarily silent, as manual chest compressions were begun – each of us processing the horror witnessed minutes before in the debris of the crushed building, the lifeless bodies of children and their parents left there until more ambulances arrived, the living evacuated first.

Jamaal then spoke aloud, to the young man, to us, to himself – “breathe”. He repeated the word, over and over. Breathe. We breathed together, stillness within the chaos of the world outside, pause within the presence of the ebbing life in front of us. Held together in what little we had left to offer, a hand held in ours, a life acknowledged and grieved.

A LIFE SURVIVED

Advertisement

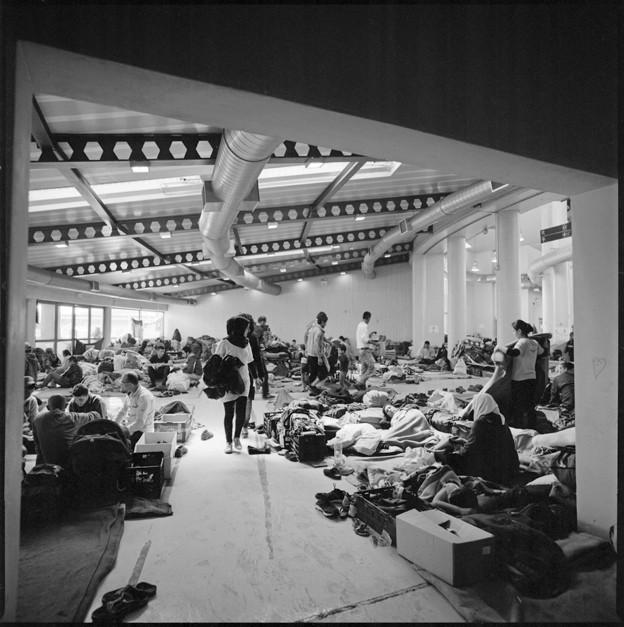

Six months ago, the presence of another kind of mourning. In a refugee camp in Lesvos, Greece, Nadia – woman, parent, survivor – stands at the door of her prefabricated shelter, a makeshift home in exile. Nadia is Yazidi, from Sinjar in Iraq. In 2014, ISIS launched a genocidal attack on her community. Twenty-three members of her family were killed. Her three older brothers were executed, one by one, in front of her.

Nadia was gang-raped in the presence of her eldest child, who was three years old at the time. Her younger sister, a student and wheelchair-user, was abducted during the attack and never found. Her name, Leila, is now tattooed on Nadia’s forearm, which she touches frequently as she speaks of her.

Nadia has PTSD symptomology, but trauma is no longer considered among vulnerability criteria in asylum claims, here. We sit as we pore over her documents, tattered fragments of a life lived, pre-war. Birth certificates, though none for her youngest two children, that need to be translated and notarised; medical records from the various refugee camps where they have sought safety; psychological assessments that speak to her pain, shame, disassociation and recurrent despair.

She hands me photos of her family, salvaged by a relative, of her before the violence visited on her life, of identity past fragmented flight. Nadia speaks of her exhaustion, when she allows herself to feel it – and of how she searches for reminders of hope, for a future different to the limbo she now navigates, and endures.

We sit for hours, over days, trying to resource her and bolster her case, amassing the endless documentation that might allow her family to continue their journey.

When we part, I press into her hand, discretely, funds gathered by friends, women in Dublin, for women in the camp. Embarrassed, she initially refuses, and I grasp for phrases in Arabic to lessen her shame. I speak of the women back home as sisters, as women who know of her suffering, strength and courage, telling her that the funds are the humblest expression of that solidarity and respect.

Nadia collapses into my arms when I mention the word sister, sobbing for the one absent – for Leila. We hold each other for what feels like hours, her grief like waves over us both. Remembering Jamaal, I say, in Arabic, breathe. We breathe together until she is back, stabilised in a present that threatens to overwhelm, a present she continues to survive.

Advertisement

BREATH HELD

Now a different kind of pause, catalysed by a pandemic that has brought the proximity of mortality, the vulnerability of life, home to so many. A global shared trauma, though one still acutely mediated by poverty and privilege. The personal dissonance of having witnessed so much violence and grief through years spent in war no longer as present – as conversations in my country of birth, my now home, suddenly take on a new gravitas, more meaning.

Our family Zoom calls momentarily bring the five countries we inhabit, all under lock-down, closer. We hold presence, reminiscence and moments of worry – some voiced, some silent – around those more at risk. We listen to the descriptions of my mother, a trauma therapist, about the frontline health-care workers she is supporting, of their strength and struggles.

We unearth and share photos of our lives together- mapped by movement and so much love. Glimpses of childhoods lived in a myriad of countries before we began our own trajectories of migration.

My phone is full of messages – friends and colleagues from the past decades reach out and re-connect across borders. Social care workers in New York and Haiti, paramedics in Barcelona, human rights defenders in Mexico, educators in Palermo, psycho-social teams in Lebanon, friends in camps and undocumented limbo all over.

Amidst them all, a voice message from Dunya, an Iraqi single mother in another refugee camp, with her two children, in the mountains. She speaks of waves of anxiety, of remembering to breathe and of tenuously held hope.

Advertisement

Maybe now, she says, something will change.

To donate to refugee Search and Rescue work in the Central Mediterranean sea:

https://www.openarms.es/en/donate

• All pix by Marcelo Biglia

*Some names have been changed...