- Culture

- 13 Feb 24

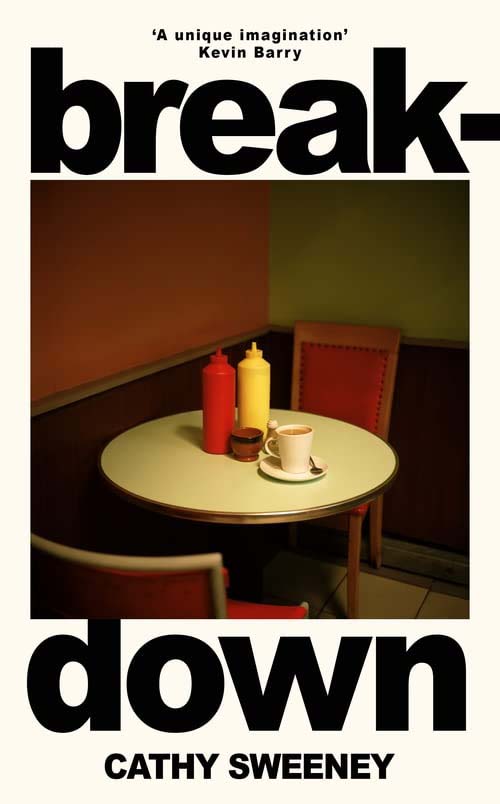

Cathy Sweeney discusses her stellar debut novel Breakdown, the compelling story of a woman who walks out on her cosy suburban life, intent on never returning.

I start my conversation with writer Cathy Sweeney by asking if she’s a fan of Bruce Springsteen. She laughs. She knows the famous opening line from his hit ‘Hungry Heart’: “Got a wife and kids in Baltimore Jack/ I went out for a ride and never came back.”

Such apparent caprice is at the heart of Sweeney’s debut novel, Breakdown, which follows Modern Times, her critically acclaimed 2020 short story collection.

Breakdown is the story of a middle-class woman waking up one winter morning, next to her husband, in their cosy suburban home, and without conscious purpose, walking out the front door, to never return. She simply drives away, then takes a train to Rosslare and boards a ferry to Fishguard in Wales.

The shadow world that lurks on the edge of motorways, service stations and terminals – their emptiness, pseudo-futuristic aesthetic and ominous quality – is expertly captured by Sweeney’s acute antenna and piercing eagle eye. The novel zips along, in a minimalist style that makes the reader want to drive on to the next scene – the definition of a page-turner. When Cathy tells me her screensaver is an Edward Hopper print, it makes perfect sense.

Does she listen to music when she works? “I love a washing machine!” she laughs.

Advertisement

“But no, I’d be too distracted by music. I like white noise. Also, I wrote sections on bus journeys between Cork and Dublin to see my daughter [writer Lucy Sweeney Byrne] and in coffee shops. I like the feeling, and have done since childhood, of the world going on around me.”

Breakdown is driven almost solely by the narrator, who remains nameless, detailing her road trip, something which “mothers are not supposed to go on”. She hoovers up detail, like the fonts, peskiness and mistaken grammar of road signs, and the hilarious vacuousness of cardboard neighbours. “She told me once,” the narrative rus, “when we were all a bit drunk that if there was fire in her house, the first thing she would save would be her Dyson hairdryer.”

The narrator also has the sharpness to tell apart the stories we live by, versus the truth of who we are. It is evident that Cathy treaded the actual route of the road trip.

“It was to try and get the tone,” she clarifies. “I suppose for me, it’s all about voice. I started writing the book in autumn 2019. And then, of course, we couldn’t go anywhere for the next two years. But that was actually a good thing, because I probably would have stayed on the road a bit too long. Because it got cut, you have to magnify what you’ve seen.”

And the fascinating character who remains nameless? “I feel that we all carry around the lives we might have led inside of us,” she asserts.

“You could call her an alter ego of some sort, but also an amalgam of many women I met at a particular time, heading into middle age. I had to dig deep to find her voice and her; it came out of experiences, listening to women, watching them. I drove around South Dublin, kind of stalking people’s houses. I’d park up and watch the morning happen.”

Advertisement

The descriptions of mental breakdown, meanwhile, have the ring of authenticity. “What I liked about it was that she very much didn’t know herself at all,” Cathy explains. “And maybe she still doesn’t, but she now knows she doesn’t. And I suppose that was the truth she was after. It’s a bit like you’re driving along the motorway and you get scooped into a lane – she just got sucked into a story. She was spending a vast proportion of her life propping it up.

“And so, when she does something that is so rare, which is going into drift, what she finds, ultimately, is not answers but questions. I didn’t want to minimise the pain and suffering, because there’s real loss, but there’s also the gaining of aliveness. I felt she had gained a sense of being alive on the planet.

“There is a trope in literature of the middle-class woman who goes rogue and they get terribly punished – Madame Bovary, Anna Karenina – but I thought, ‘What if she doesn’t get punished? What if she just lived?’”

No Compromise Allowed:

In the novel, the narrator explains that in Japan, so many people disappear from their established lives, that they have a word for them – Johatsu: the evaporated people. What in our culture makes this common?

“I think myth and reality are quite enmeshed in Ireland, but I don’t want to get into any grand statements, because I don’t have any,” replies Sweeney. “But there is a little bit of performing the country. There’s quite a lot of dissonance between where we want it to be and what it is, because they’re such lovely pictures, why would we want to get rid of them? I think that people find it very hard to tell some of their real stories, because the narrative is a culture of positivity and that culture can be quite insistent.”

How’s the reaction to the character been? “I only know a few people who have read it,” she replies. “I suppose I’ll find out. It’s kind of a strange little rule in my head. I don’t really ever believe anyone’s gonna read it, so it’s always slightly surprising to me that it turns into a book. But I’d be terrified to censor myself. Because why write them?

Advertisement

“I started writing, I think, as a way to stay breathing. I was primarily writing out of a need to express what was in my head – thoughts, ideas, imagination. I would never compromise on it; I’ve had enough life experience to know how easy it is to compromise on things.”

Cathy studied English at Trinity College and then taught at secondary level for many years before turning to writing. So, what’s next?

“I’m working on a new novel that’s completely different,” she replies. “It’s historical fiction, based on a very particular period in the life of Oscar Wilde. When he came out of prison, and within months of writing De Profundis, he set up home in Naples with Lord Alfred Douglas. And they were there from September 1877, until Douglas left in early December and Wilde left in January.

“And we’ve excised it. I mean, largely, it’s kind of, ‘He went to jail, came out, died in Paris’. But Naples is this period when they actually tried to live as two gay men setting up a home together. It was doomed, but I love doomed scenarios. The thing with Breakdown was I knew I wouldn’t be able to write anything else until I wrote it. I had to write that novel, I had no choice. And now I’m finished, I can do what I like. And now I’m really doing what I like.”

• Breakdown is out now.