- Culture

- 02 Apr 24

Colum McCann on Diane Foley: "She's a genius of compassion"

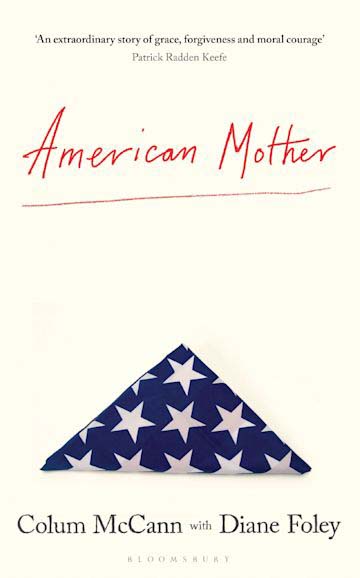

Colum McCann discusses his new book American Mother, which tells the story of Diane Foley, mother of journalist James Foley, who was murdered by Isis.

Award-winning Irish author Colum McCann’s latest book, American Mother, tells the fascinating and often harrowing story of Diane Foley, the mother of James Foley, the US journalist abducted by Isis in 2012 and beheaded two years later. Whilst held in captivity in Syria, James was regularly beaten by a group the media dubbed ‘The Beatles’, four Isis members with English accents.

American Mother opens with an extraordinary 2021 meeting in Washington between Diane Foley and one of those Isis members, Alexanda Kotey, who’s serving a life sentence for his crimes. Reading the account – minutely detailed, with McCann having accompanied Diane as a family friend – it’s remarkable that a complex geopolitical moment is distilled down to an encounter between a prisoner and the mother of a man he murdered.

“I just think Diane is such an extraordinary person,” reflects McCann from New York, where he has lived for the past 30 years. “She’s such a genius of compassion, and I thought if I can do anything, I can help her articulate her story. She really wanted her story to get out in the world – not for herself, because she’s not that kind of person – but in order to talk about her son. That was important for her.”

McCann first reached out to Diane after seeing a photo of James reading Let The Great World Spin, the author’s acclaimed novel about Philippe Petit’s 1974 tightrope walk across the Twin Towers. It was the meeting with Kotey that convinced him he had to write something about Diane’s story, with McCann joining the trip after family members were understandably hesitant to go. During the meeting, Kotey holds forth on different aspects of Islam, but did he strike McCann as a genuine intellectual, or was he – to be blunt – something of a bullshitter?

“A bit of both,” the author considers. “Everything I had read beforehand pointed to him being a standard thug. There was all this stuff about him in the British press being a football hooligan – apparently he was a QPR fan. He’d been put in this box with the ‘Beatles’ thing. It was easy to compartmentalise him as a young, radicalised, working class kid. But from the moment I went in, even just looking at him, I knew there was something more about him.

“First off, right in front him, he had Patrick Radden Keefe’s book about Northern Ireland, Say Nothing. The curious thing was that I’d blurbed that book! He had no idea that my name was literally sitting there in front of him as we sat down. I ended up asking him about his interest in Northern Ireland, and it became obvious to me that I was dealing with someone with a lot more smarts than he was given credit for. When he talked about Islam, he talked about it in a fairly profound way.”

However, there was another side to the story.

“Both parts of your question are correct, because he also was a bullshitter too,” Colum notes. “He also thought he was the smartest man in the room, and that he was pulling the wool over Diane’s eyes. Diane is not immediately incredibly articulate, but emotionally she’s incredibly astute. It was very interesting, it was like a game of chess. We started at nine in the morning and had our first coffee break around 11. Diane and I looked at each other and went, ‘He’s a lot different to what we thought.’ And we both kind of liked him.

“Or maybe not so much liked as understood him. I in particular understood him because he’s a Brit, but he’s a working class Brit who doesn’t align himself with British politics at all. So, he was thinking much more along the lines of Ireland. He was researching the IRA because of the cell structure and things like that, and its similarities if any to Isis. Of course, he realised I was Irish, so he was asking me questions.”

While many important resistance movements have utilised violence, Isis’ indiscriminate slaughtering of civilians is more difficult for many of us to understand.

“He was talking about doing things in the fog of war,” says Colum. “That he did it because he was a soldier of Islam, and that he didn’t think about the ramifications for non-combatants, and the morality of it. There are all sorts of issues, because Jim Foley had become a Muslim. Kotey knew this, and there was an edict against torturing Muslims. He was justifying all these things and it was interesting to watch his mind turn.

“It was also fascinating because he talks in a Cockney accent, and you realise he was born in east London, and his mum was from Greece and his dad from Ghana. He could have been any number of things. But he got radicalised as a teenager, went down to the mosque and then became a convert – he had that energy of the convert. So I was watching this stuff unfold in front of me and it was a great human story.

“But even more than that, you have this woman in her seventies, and she was calmly listening to him with her hands folded. She was interested in looking at him in a compassionate way. It was a profoundly human moment that had a lot of contradictory things going on all at once.”

A major part of Diane’s motivation in meeting Kotey was to say: you can’t take away my memory of my son, and I’m now imposing that on you. There was defiance in her approach.

“That’s perfectly put,” says Colum. “It’s like One Thousand And One Nights – you tell the story to keep your son alive. She was also saying, ‘By the way, you did not kill my son, because I am here to tell you who he was and what he believed in.’ So there was an element of her being slightly combative. But she also went there with the notion that she wanted him to know what was going on, and wanted to see if she could find out certain things, like where the body was buried. Which we never found out, of course.”

Having started his writing career as a journalist, McCann still considers himself one, and the idea of him writing about a reporter is another intriguing aspect of a multi-layered book. Also fascinating is Diane Foley’s anger toward the Obama administration, whom she felt did not do nearly enough to secure her son’s release. For those of us who admire Obama, it makes for surprising and uncomfortable reading.

“I align myself with you on this one, because I like Obama,” acknowledges McCann. “I like what he said and how he said it. And then, I have to tell Diane’s story. She was angrier at Obama and his administration than she was at Alexanda Kotey, seriously. It was hard for me to sit down and write those words. She goes into the Oval Office and sits with him, and he sips tea, and he doesn’t offer her a cup of tea. I was like, ‘This can’t be the Obama that I know.’

“He did turn it around and eventually listen to her. But it was hard for me to write. And then Trump turned around and did some stuff about returning hostages. That was hard to write as well, but I had to be true to her story. It’s not my story, it’s hers. That was the other thing as well – I kept myself out of the story, I didn’t want to be a character in it. I’m a reporter, a fly on the wall, and I wanted to try and capture her life, and his life. I really admire Diane. We were in Ireland and England last week, and travelling with her, my admiration doubled, if not tripled.”

Colum MCann.

Colum MCann.Away from American Mother, McCann continues to be one of Ireland’s most admired authors, with his work having been cited and quoted by the likes of Obama himself, as well as Bono and the Pope. Talk about the trifecta.

“Yeah, Obama used that quote at the G8 in Northern Ireland, which was a nice thing,” says Colum. “Given all those characters, I’d still rather have Diane quote me than anything!”

As it happens, after our interview, McCann is shooting off to a meeting with the aforementioned Philippe Petit, who has become a friend.

“He’s doing the 50th anniversary walk in August,” he says. “He’s going to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York, and he will walk a tightrope back and forth. Sting, who’s a pal of his, will sing the song ‘Fragile’, and he’s also now written a song called ‘Let The Great World Spin’, believe it or not. He’s gonna play it that night too. So Philippe and I are just going to talk about the texture of the evening. Also, I’ll get a chance to give him this book.

“Because I haven’t even explained to him that he really is part and parcel of this whole story. It’s bizarre to think about – this story has so many moving elements. But part of the reason I got involved in it was because he did his tightrope walk all the way back in 1974.”

- American Mother is out now.

RELATED

- Culture

- 19 Dec 25

Government announces €987,498 to go towards artist workspaces

- Culture

- 19 Dec 25

Guinness returns to 3Arena after more than 15 years

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 18 Dec 25

RTÉ to celebrate 100 years of broadcasting in 2026

- Opinion

- 17 Dec 25