- Culture

- 26 Aug 22

A series of nine works by David Rooney, based in Famine Ireland, were given a permanent home at the Irish Workhouse Centre last night, in a special launch ceremony attended by the renowned Hot Press artist and illustrator himself. The highlight of the evening was a speech by the singer, songwriter and author Declan O’Rourke – whose debut novel The Pawnbroker’s Reward is set in the early years of the famine.

A launch party took place last night at the Irish Workhouse Centre in Portumna, to celebrate the installation of nine works of art there, based on the Famine and created by David Rooney. David, who has for many years been a regular contributor of powerful illustrations to Hot Press, grew up just ten miles from the Workhouse Centre, in the village of Eyrecourt, Co. Galway..

The ‘Famine Artworks’ were originally created as part of a collection of 100 engravings commissioned for the BBC/ RTE documentary series The Story of Ireland, broadcast in February 2011. The five-part series, produced by Mike Connolly and narrated by Fergal Keane, explored Irish history and its impact on the wider world.

“I've been working as an artist for well over thirty years,” David Rooney said, "documenting the tumultuous changes in Irish society in newspapers, and Hot Press magazine in particular, more recently creating work for a museums both here and abroad. I feel these nine portraits of the famine represent my finest work.

"I am delighted and honoured that these specially printed panels featuring the Famine Artwork have found a permanent home in The Irish Workhouse Centre in Portumna, ten miles from where my formative teenage years were spent, in the village of Eyrecourt, where my Dad served as the local Garda Sergeant.”

Declan O’Rourke spoke eloquently of Rooney’s particular genius.

Advertisement

"David Rooney,” he said, "is a master of his craft, a living master. I do not say that lightly. Anyone who encounters his work the world over will easily agree.

"As someone who has studied and worked on the subject of the famine for a long time, trying hard to find and see, and bring the pieces back to life too — I find these artworks astonishing in their detail. It’s abundantly clear that David researched his subjects intimately.

“What I can say, is that without doubt, something extraordinary did happen when David executed the nine scenes in question here today.”

Declan O’Rourke’s speech was greeted with a rapturous response.

“It was more a performance than a mere speech,” David Rooney said afterwards. "Moving and lyrical it reflected his current work as a novelist. I was honoured to be a part subject of this oration."

Declan O’Rourke's speech in full:

Hello everyone, and good evening. I’m delighted to be back here at the Irish Workhouse Centre in Portumna, on the occasion of the launch, and commitment, of nine incredible works by the prolific and gifted artist that is David Rooney, to their new permanent, and fitting home here at the centre. The last time I was here was to visit the Dark Shadows exhibition by another gifted artist and friend, Kieron Tuohy, so you’ll be in fine company indeed David.

Advertisement

You know it’s so easy, to stand in a place like this, among lovely people, and to forget the tragic enormity of what happened here, and in many workhouses across the country…

The walls still stand. The floors still thump when you walk upon them. The corridors still ring with our speech. The general shape of the institution is still apparent. But the faces are gone. The signs of suffering humanity and horror, are gone... hidden under layers of time.

We have texts and documents, fragments of evidence, sometimes even eye-witness accounts to help us piece it back together. And they do. They are invaluable.

The role of the artist is something we could debate at length. Is it to bring things into the light and inform us? To shake things up and challenge our views on topics? To be provocative? To reproduce great beauty? It is, perhaps, all of these things – but maybe most immediately, and especially today, the job of the artist, is to help us to see, and to bring something to life, when we cannot ourselves.

I recall when my wife and I went inter-railing some years ago. We made a stop in Krakow, where we visited the camps at Auschwitz and Birkenau. The tour we took was filled with facts and figures. Tens, even hundreds of thousands. Incomprehensible numbers. They seemed to wash over our heads. I remember having trouble equating this clean, quiet, empty building with the colossal events we know unfolded there. Even the piles of shoes, hair and glasses, while certainly impressive, were too much for my mind to process – until we saw the photographs of single faces. Human faces, like you and me, and members of our families. Then it was real.

The role of the artist is to gift us sight.

David Rooney, the artist, is so gifted, and technically capable – and brilliant – that I would use the word fluent. Fluent – because I suspect he reached the point long ago of being able to just think of an object and simultaneously it is brought to life by his hand.

Advertisement

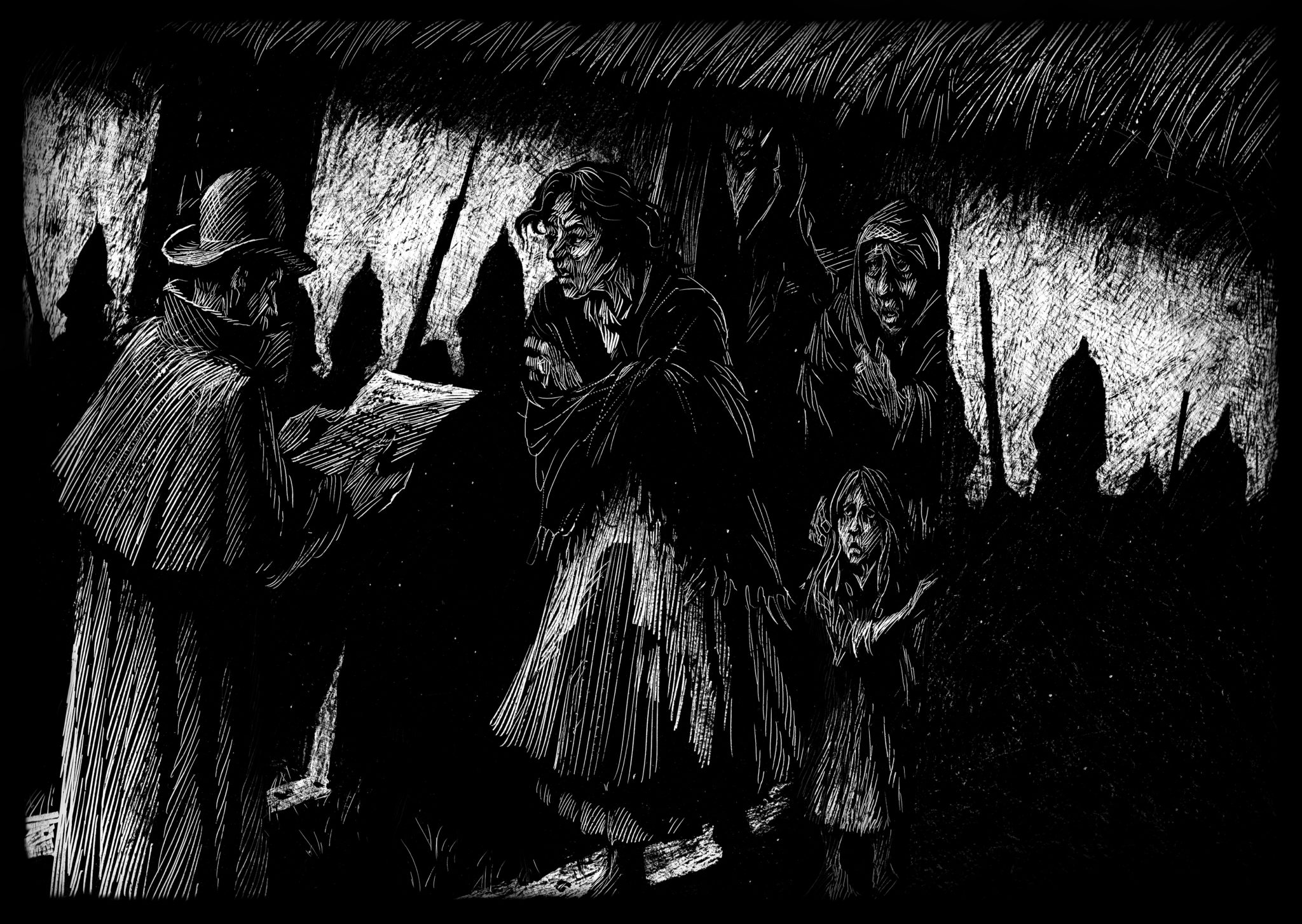

- The sadness expressed in the shoulder of the woman carrying her dead child,

- The invisible spectre of the wind, driving back the hair over the forehead of a man who, forlorn, stares into his empty future.

- Golden light kissing the brim of a hat

- A bayonet silhouetted against the whitewashed wall of a cottage about to be tumbled.

This gift, of course, belies the application to his craft across thousand upon thousands of hours, and decades perfecting, niggling, obsessing over and clearly enjoying every nuance and detail of what he creates – because, make no mistake, every detail whether in light or in shadow – is considered, and created intentionally, even if by now, it feels automatic to David himself.

But it takes more than skill to be an artist. Perhaps the most important ingredient is what you might call, a listening eye.

One that pays attention, and that studies nature, and human nature, from the way a person stands, to the motion of the sky and everything in between. Interest. Attention to detail.

An artist develops a fascination not only with a subject – such as the Famine – but with any tiny element he encounters in his travels. When he hones in on one, he drinks it up, interprets it, mimics it, toys with it, becomes it, and eventually reproduces it, infused with some of his own magic and style.

Age and experience only add to the palate.

Vision, which is different to sight, comes after sight — and when one has become good enough to play with multiple elements and put them together at will, he will approach a project by first deciding what might be the most evocative angle to view a scene from, who will fill it, how he will draw the viewers eye to a particular part of the piece, and there unveil the reality of what’s happening within – then we have composition.

Advertisement

This is something David does incredibly well.

But deeper still, an artist does not merely draw, write, sing or dance to something they do not feel a resonance with. Feelings – which he has also spent a lifetime studying – drive the ambition to create, to honour something, be it an object, a person, or an event. To recognise these and to work from them, is the true capstone of an artists gift, because they infuse his work with a humanity that we, as an audience, can relate to – and therein find our own feelings of empathy, of brotherhood and humanity.

The pieces an artist creates that do not thrive on this connection, while still brilliant, may at times feel like stepping stones, practice pieces, and studies to the working artist. But something different happens when a connection IS established. It is then that every other element comes together in harmony, in symphony, and in force.

While he was creating ‘The History Of Ireland’ a series of one hundred such engravings that he executed at a staggering rate of one a day, of which the nine we see here were merely one section – David says that when he reached the period relating to the famine, something happened... he knew these people:

- The woman in the eviction scenes strong and determined against all odds, her partner in life falling apart (see below).

- The man searching for something that can be saved from the doomed crop;

- The mother who, watching a ship knows her only option is to leave.

I can’t speak for the other ninety-one scenes, which I can only imagine are truly brilliant too. It just makes me jealous really.

Advertisement

But what I can say, is that without doubt, something extraordinary did happen when David executed the nine scenes in question here today. All of his gifts and skills came together to forge what one can only call a mastery of his craft.

As someone who has studied and worked on the subject of the famine for a long time, trying hard to find and see, and bring the pieces back to life too — I find these artworks astonishing in their detail. It’s abundantly clear that David researched his subjects intimately. If I didn’t know better I’d imagine he spent time in a workhouse himself, or was on an eviction squad. He clearly immersed himself in the period anyway, and has, to my mind, brought honour to the subject, and done it incredible justice.

I, myself, have known David for some time, and have even had the honour of working with him. On a number of occasions, his work has complemented, enhanced and taken my own work to another level.

David Rooney is a master of his craft, a living master. I do not say that lightly. Anyone who encounters his work the world over will easily agree. He has had a suitably illustrious career to date, but in my opinion is yet to be fully recognised. Anyway, I don’t want to give him too much of a big head ...

As both an admirer of his work and as a friend, it’s my honour to have been asked to speak on his behalf here today. It’s also great to see that his work has come full circle on this occasion, and reached this wonderful, deserving facility, so near to home.

In conclusion, it’s a truly wonderful and happy occasion to see David Rooney’s nine outstanding works find their place here at the Irish Workhouse Centre in Portumna, where they can be appreciated by those who most need to see them; where they will remind us of what happened here and help us to see with our own eyes, what we ourselves, between the walls, the floors and the sky, cannot.

So — if you’ll care to join me now in raising your glasses, it is with great, great pleasure that, just ten miles from where he spent his formative teenage years in the village of Eyrecourt, I now declare David Rooney’s nine artworks on the subject of the Great Famine, officially launched.

Advertisement

David Rooney explains the background to the Famine Artworks:

The Famine Artworks were originally created as part of a collection of 100 engravings commissioned for the BBC/ RTE documentary series The Story of Ireland.

The five-part series, produced by Mike Connolly and narrated by Fergal Keane, explored Irish history and its impact on the wider world. The series was first broadcast in February 2011.

The technique used in The Famine Artworks is scraper-board, an engraving medium where black ink is scratched away with a surgical scalpel revealing a white chalk-covered board beneath. It is a process of constant revelation and always contains surprises, very apt and suitable for the depiction of history.

By and large, the events I was called upon to illustrate during the course of the project were tragic, including a series of foreign invasions and a litany of broken promises – with all efforts at self determination or rebellion thwarted or crushed. However, it wasn’t until I came to the Famine period that the the subject-matter began to really resonate with me. I felt utterly connected to the people I was conjuring into existence, and of course I truly was. My mother’s family came from Tuam and my grandfather was born in New York to post famine emigre parents, who both died when he was still a young boy. Those great-grandparents were children of the famine era.

I have been working as an artist for well over thirty years, documenting the tumultuous changes in Irish society in newspapers, and Hot Press magazine in particular, more recently creating work for a museums both here and abroad. I feel these nine portraits of the famine represent my finest work. The characters came to me unbidden, I had little consciously to do with their appearance, so credit goes to the forces that channel such energy. There’s no greater reward or feeling as an artist when all you have to do is get out of the way and let it happen.

I am delighted and honoured that these specially printed panels featuring the Famine Artwork have found a permanent home in The Irish Workhouse Centre in Portumna, ten miles from where my formative teenage years were spent, in the village of Eyrecourt, where my Dad served as the local Garda Sergeant.

Advertisement

• ‘The Story of Ireland – Famine Artworks’ by David Rooney can be viewed at The Irish Workhouse Centre, Portumna, Co. Galway.