- Culture

- 25 Oct 23

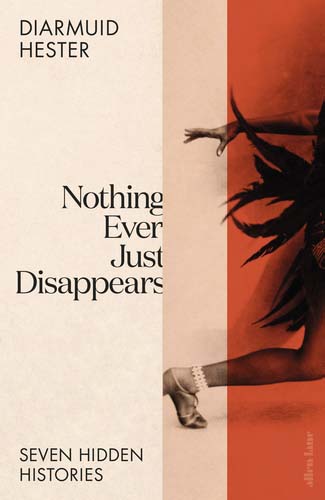

Cambridge academic Diarmuid Hester on his compelling new book, Nothing Ever Just Disappears, which examines the central role of queer spaces in 20th century life, cult artistic heroes Derek Jarman and Dennis Cooper, and the creeping censoriousness in modern culture.

In his new book, Nothing Ever Just Disappears, Irish Cambridge academic Dr Diarmuid Hester fascinatingly considers the role of queer spaces in 20th century society, and the incalculable cultural capital lost when those spaces are forgotten, via an examination of seven figures, including EM Forster, Josephine Baker, James Baldwin and Claude Cahun.

The jumping off point for Hester’s project was his visit to the Dungeness, Kent cottage of the great Derek Jarman. As well as an exceptional filmography as a feature director, Jarman’s phenomenal career included overseeing one of the greatest ever cinematic production designs for Ken Russell’s cult classic The Devils, as well as collaborations with a remarkable range of musicians, including the Sex Pistols, Marianne Faithfull, Throbbing Gristle, The Smiths, Suede and Pet Shop Boys.

“There’s also Modern Nature, this journal he wrote of his time after being diagnosed with Aids, when he spent a lot of time in Prospect Cottage,” says Hester. “As you say, it’s a fantastic body of work, and he’s having another moment now. I don’t know if you know The Last Of England, which was soundtracked by Genesis P-Orridge of Throbbing Gristle – it’s a really industrial soundscape. Ultimately, it’s a succession of quite striking, generally violent, but beautifully saturated images of Tilda Swinton in a bridal gown, getting married to her paramour.

“Subsequently, the groom is taken away and shot. The ending is this tragic twirling of Tilda Swinton beside a bonfire. It’s such an explicit commentary on England in the ‘80s. There was a long time where Jarman kind of made me cringe! Cos he’s so earnest. I grew up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, where you couldn’t say anything earnest, because you’d be shot - everything had to be ironic.

Advertisement

“The Last Of England is basically, ‘Thatcher is a fascist and will shoot your husband.’ It is categorical, and I think what people are responding to in Jarman’s work now is that earnestness, and that willingness to be categorical about things, when we find so much prevarication in politics, social media and activism even, where people are saying one thing and doing the next. Somebody like Jarman is a saint! His willingness to demarcate the ethically good from the bad, is something people are in dire need of, and that’s why he’s resurfacing as somebody of interest.”

Following Jarman’s untimely 1994 death, Prospect Cottage became something of a shrine for fans. When it was in danger of falling into falling into private hands, a crowdfunding effort involving Swinton among others raised £3.5 million, ensuring the building could be maintained as a heritage site. Other figures Hester looks at in the book include Cambridge’s own EM Forster, author of classics like A Room With A View and Howards End, whose dual character the author suggests was mirrored in his physical surroundings.

”He’s very interested in spaces, for one thing,” says Diarmuid. “Also, social structures and how they connect with one another, and how in many ways, they house human feeling. And how human feeling can’t be contained by either social or physical structures. That’s certainly something I found was a characteristic of being in Cambridge in the early 1900s. Forster was learning all about ancient Greece and its freedom for homosexual men of class. But he was living in this educational hub that was very conservative and repressed, so that dichotomy is so much a part of Forster’s life.”

Nothing Ever Just Disappears also explores how London’s Suffragette movement subverted traditional spaces like the street and home.

“The French scholar Michel de Certeau has this idea of place and space,” says Hester. “Place constitutes the buildings and so on that you’re surrounded by, which are preordained and prescribed in some way. But space is how those spaces are used and practised. He talks about the idea of spatiality, and that idea of subversion you’re talking about with regard to the Suffragettes, is an example of an alternative approach. It’s a kind of détournement, opening up new possibilities that were unanticipated by the creators of the places. I love the idea that you can recode places.”

Advertisement

Derek Jarman Home in Dungeness

Derek Jarman Home in Dungeness

I first become aware of Hester a few years ago, when he authored Wrong, a critical biography of cult US author Dennis Cooper, whose five-book George Miles cycle became an all-time classic of transgressive fiction in the ‘90s. Heralded by Bret Easton Ellis as ‘the last literary outlaw of mainstream American fiction’, Cooper’s work fitted alongside other ‘90s radicals like Irvine Welsh and Chuck Palahniuk.

His work was also strongly tied up in rock: a fan of bands like Blur, Husker Du and Sebadoh, Cooper also wrote liner notes for Sonic Youth. How did Diarmuid first become a fan of his?

“I was doing a Masters in Brighton and he was part of a seminar I did,” he recalls. “But he was kind of presented as ‘the bad gay’! Like, here’s how to do gay literature the bad way. Because he didn’t present a palatable image of happy, domestic gay relationships. Especially at the time of Aids, when there were a lot of activists calling for positive imagery, which would counteract the negative appraisal in mainstream American culture and politics.

Advertisement

“I was obviously very interested! You can’t be a tattooed Irishman in Cambridge and not be in some way drawn to Dennis Cooper (laughs). Then I logged onto his blog, which around 2005 was this amazing hub. First of all, I was going, ‘Holy shit, I’m talking to Dennis Cooper.’ You’d leave a comment and he’d reply. I think that’s really important to him in terms of supporting new writers and nurturing young people, particularly those doing similar work to him and so on.

“So I got friendly with him through the blog, and then I got friendly with lots of people on the blog who introduced me to a lot of the marginal queer work that has really defined the way I look at art. There was a 10-year period where I was on the blog and reading his work, and I did a PhD on him as well.”

What was the first Cooper book he read?

“It was Frisk,” Diarmuid responds. “People ask me, ‘What Cooper book should I read? - and I never suggest Frisk! Because it’s such a hardcore introduction to some of the themes he deals with. The Sluts is similar.”

Bret Easton Ellis reckons The Sluts could be Cooper’s masterpiece.

“It is an absolutely fantastic book,” nods Hester. “Weirdly enough, it won this massive gay fiction award called the Lambda Prize. That shows the shift that was going on between when he was first published and when he published The Sluts. He was received by a large gay public at that point.

Advertisement

”After that, I read the rest of the George Miles cycle. The concluding part, Period, is for me the pinnacle of literary experimentation, but also feeling and the closeness of grief. There’s also a weird rural gothic quality to it as well.”

Of course, much like American Psycho author Ellis, the intense sex and ultraviolence of Cooper’s work begs the question of where he fits in today’s increasingly sanitised cultural landscape.

”People still want to explore those feelings,” suggests Diarmuid. “They still want to be challenged and people continue to come to his work. Closer is being reprinted later this year and that interest is absolutely still there. We’re operating more and more now in a culture of censoriousness and self-censorship, and concern about thinking the wrong thing, even. One of the lines in The Sluts that I always remember, is where one of the commenters on this forum is trying to get the other guys to be more ethical in their desires.

“And one of them says, ‘Our fantasy lives are not a police state’. It feels like the self-censorship has the possibility of moving into our minds at the moment. We’re going, ‘Am I suppose to think that? Am I suppose to fantasise that?’ There’s a lack of freedom there, and Dennis offers a kind of capaciousness around what your fantasy life, or your imaginative life, is going to be, for good or for ill. This is all human imagining and part of the human experience.

“People are still very interested in that, and it’s more important than ever that there should be an outlet for it.”

I couldn’t agree more, although it’s increasingly hard to find modern literature with transgressive sensibilities. Does Hester feel the censoriousness is being imported from US academia?

“I might have take the fifth!” he quips. “No, I’m joking. Let’s say with queer studies in particular, which is the area I work in, I was trained by Alan Sinfield at Sussex. Alan was a working class British scholar, a queer professor of Shakespeare, but he was very attached to real life. He set up this Masters in order to have queer political activism be part of the academy, and for it feed into what was going in scholarship at the time.

Advertisement

”But he set it up in the late ‘80s, and I think what happened between that point and now, is that an American academic model of queer studies took over, which was initially shored up in Ivy League colleges. Those academics had some contact with political activism, but very quickly removed themselves from the real life of politics and individual experience.”

James Baldwins French Village St Paul de Vence

James Baldwins French Village St Paul de VenceIt seemed to develop from there.

”They started talking in a very theoretical, deconstructionist language that proliferated,” Diarmuid continues. “Because it wasn’t really concerned with that tangible connection to communities, it could be sold in the market like every other American product. I think a lot of places, including England and Ireland, have bought that wholesale.

“There is a disconnect between the theorisation of reality, and the use of a rarefied vernacular in that establishment mode, and real life. I feel that’s a very good example of the disconnect that’s infiltrated modern life. It’s nuanced, academia is not wholly responsible, but there’s a lot in that drift to the abstract.”

I think class is a huge amount to do with it. Coming from a working/lower middle class background, to me, the likes of Cooper and Ellis - as with controversial authors before them, like Anthony Burgess and Hubert Selby Jr - simply took an unflinching look at the intensity and grittiness of real life experience.

Advertisement

”But it’s also popular culture,” adds Diarmuid. “Because he was part of a group of writers, like Kevin Killian, who I talk about in the book; Dodie Bellamy, who was Kevin’s wife; and Lynne Tillman. They were all writing about pop culture, but in a way that valourised it as an emotional, psychological and even spiritual experience.

”It’s no surprise to me that Try was the Cooper book that hooked you, because it’s just so much about music, zines and all of that. Dennis is a filmmaker now. In his archive, he’s also got loads of unfilmed screenplays for porno.”

So do I!

”Who doesn’t?!” laughs Diarmuid. “So I think he’s gone from writing screenplays of his own stuff, to cutting out the middleman, as it were.”