- Opinion

- 05 Jul 22

Crisis in the Horn of Africa: Revisiting Michael D. Higgins' account of his 1992 trip to Somalia and Kenya

President Michael D. Higgins recently shared a powerful video, speaking out about the crisis in the Horn of Africa. In the speech, he references his 1992 trip to Somalia and Kenya – which he wrote about at the time in his column for Hot Press, describing his experiences there, and the suffering he witnessed. Read his original 1992 column below:

A chronicle of war, famine and the struggle for human dignity in Somalia.

There is no experience I have had, in any refugee camp, in any war zone, that could have prepared me for the scale of horror that is Somalia. I find it difficult to describe even now, at a distance of over a week, as I work through the notebooks I wrote each day.

On a Wednesday afternoon I decided to go to Somalia. In Nairobi on Friday I was briefed at a number of meetings on the work of the Aid organisation and in particular by the Irishman Geoff Loane who is in charge of the International Committee of the Red Cross’ impressive work in the field, in this devastated region.

Flying North to the camp of Mandera in North East Kenya along the way you can see the shattering effect of the drought. The first sight of the camp is like a city of beehives, alongside which lie hundreds of little ridges, the graves of children, women and men. People die here every day.

There are 50,000 people in the camp, more than double the number in Mandera itself, it gives an idea of the scale of the refugee problem Kenya is carrying when one remembers that there are 400,000 Somalian refugees in drought-stricken Kenya.

In Mandera food is beginning to be distributed on the scale that is needed but there is no defence for the bureaucratic delays and the sporadic distribution nonetheless. Seeing this devastation first-hand, I understand the rage, the anger, and the emotion of President Robinson when she gave her press conference immediately after leaving Mandera.

In the eight days I spent in Somalia I could not get away from the obscenity of the country being flooded with weapons at the same time as walking skeletons moved slowly, staring out impassively ahead, waiting to die.

How can one not rage at the immorality of the actions of one superpower, then another, filling a country with weapons and then walking away? The reality of Somalia's terrible vulnerability was known before the despot Siad Barre fled in January 1991.

Again, every day, I thought of the weapons-producing and selling countries, of those who are still selling instruments of death into Africa and the South of the planet in general. I thought too, of the absence of the international media. There was just one North American and one British crew working in Somalia, where 1.5 million people are starving and 2.5 million affected by the famine out of a population of 7.6 million.

How different it was to the Gulf War when camera crews competed to bring us pictures of every single rocket as it was launched. How true indeed that Somalia's plight would be different if it was an oil rich country.

From its station in Mandera, Trocaire is establishing a project in Gedo Province. Gedo is located in Somalia near the North-Eastern border of Kenya, across from the refugee camp at Mandera.

I stayed in the house Trocaire is renting, where I meet field officers Joe Feeney and Kathleen Fahy, and field staffers Zebbe, an agronomist and Stephen. It is basic. It has a pit latrine and in a cubicle a bucket hangs, if you have the patience to let the water you have drawn from the well trickle on to you. The rural training suggests you use a more direct method.

I watched as the Elders, who almost certainly offer the only basis from which the Civil Society can be reconstructed, handed over lists to Trocaire workers of those who were ready to plant seeds when the short rains came.

If the seeds were eaten they would kill, so Trocaire gives out food with them. They have also been examining the wells which are dotted everywhere, dry and abandoned, a danger to life. Some of the repairs to the infrastructure are simple. The aim is to have a secure, safe well in every village.

Trocaire also have a programme in the five districts of Gedo, training health workers to carry out nutrition surveys and bringing basic health care to mothers and children.

While all this is happening, there is a new dialogue being constructed between, and within, the clans that make up the Somalian Nation.

I met the Chief of Chiefs and the Elders, who gave a moving speech and was very grateful for Ireland's interest. On the night before an old man had said to me: “Welcome. It is a holocaust. We have been committing suicide. Thank you for coming." That feeling was everywhere.

Again and again I thought of the possibility that Ireland might pioneer an imaginative foreign policy in the developing world. Whatever latter-day revisionists may write, there is in the Irish psyche a memory of famine, of the consequence of colonialism and a humanistic impulse born of a decent sense of interdependency.

Travelling into the province of Gedo we reached the City of Luuq, which is controlled by the Islamic Fundamentalists. Once a city of maybe 200,000 people, It now accommodates just 50,000 who have made their way back. A laboratory technician and a male nurse run the makeshift hospital. Saudi Arabia is willing to fund the rebuilding of the Mosque but has not offered to help with the hospital.

The camera crew from E.M.G. are with us, including Gerry McColgan, Ken O'Mahony and Karl Mirren. Ken and Karl, camera and sound respectively, are regular readers, and are anxious for me to point out that they had only one night off in Nairobi which they spent attending a revivalist meeting and drinking tea with a lay preacher.

Journeying through Somalia, relationships are tested and I felt that the long silences which prevailed at times as we tried in vain to make sense of what we saw were drawing us together in a way which helped us to support each other. I valued that and will always remember it.

In the hospital at Luuq a woman is looking straight ahead. Malnourished, she has a baby at her breast and she is trying to care for her sick child of about three years. I can still see her face. I wondered about the act of filming such a person. Her sense of privacy is important — yet she too will say, through the interpreter, that the world should help and come to know the pain of Somalia and its people.

Travelling to Luuq in daylight took nearly five hours. Coming home through desert tracks in the half light was more difficult. The journey was broken for the inevitable repair of a puncture, as well as for the prayers of the drivers who took their mat on to a space nearby, positioned themselves, bowed and prayed.

I thought then of the question I had been asked in Luuq; Who is your prophet? Luuq struck me as an extraordinary place; medieval in its defensive structure, it is surrounded by the Juba river and entrance is gained through a gateway beyond a protected bridge. Even in the midst of great want and death, women were making and selling tea; thus as ever do they carry the burden of famine and war.

Michael D. with Omar and Trocaire's Sally O'Neill in the pharmacy at the Red Cross' hospital in Northern Mogadishu

It is utterly wrong to construct the present conflict between Mahdi and General Aideed as an indicator of a violence prone people. When, in the 19th century, Richard Burton wrote of Somalia he spoke among other things, of their rich oral poetic tradition.

The Somali language was not given written codification until the 1970s. It was 1976 before the first novel was published here. In the last century a person with a new word would travel hundreds of miles for a poetic contest in a village, hoping that a new word, as one man said, would defeat his opponent who might have defeated him earlier with alliteration.

There was something eerie about travelling the roads, and repeatedly encountering abandoned villages. Everywhere there are burned out vehicles, skeletons of cattle, huts that are roofless. The destruction is of a scale that is simply unimaginable.

Beyond the immediate food aid, there is a mammoth task of reconstruction to be undertaken. Nobody has been at school for two years. Every family has at least one rifle.

In refugee camps you meet those who have fled from urban areas, such as Mogadishu. They are gathering together along the Clan lines. From the five basic units subdivisions are made and people have gone in search of their own group.

Those who have not finished their schooling introduce themselves as "the young intellectuals". There are older professors too and it is from a group of these I received a request that the National University of Ireland help in the task of reconstructing the National University of Somalia.

What I read now in the notebooks makes reference, again and again, to the children. In this country where few live beyond 50 years the children are everywhere and they are in such great need.

In Garissa, 120 miles inside the Kenyan border, the local bishop Paul Darmanin is assisted by an Indian nun and a few others in running a feeding centre. Here 500 children a day are fed. He is helped by funding from Trocaire.

In the camps at Mandera and Ifo, the short rains will increase the threat of cholera. If the rains bring hope for the seed plantation, they will also bring even more death to the camps. Hardest of all to witness are the bodies, often covered in sores, their bones bare and brittle. Above all the beautiful eyes staring out, hopeless.

Many of these starving people will need up to three weeks preparation with vitamin enriched liquid foods before they are able to digest solid food.

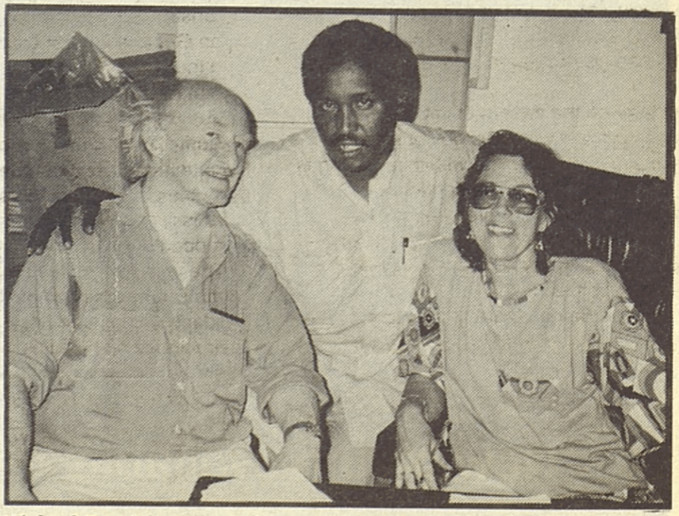

Meeting orphans with two Somali aid workers at Garissa Camp in Northern Mogadishu

Baidoa has the highest reported daily death rate, 250 per day. The journey there will be a long and tortuous one. On the day I meet Goal volunteers — Dr. Tim Gleeson and nurses Mary Scully and Helen Fitzgerald. Later I hear of their work in Mogadishu and Afgooye. Indeed, it is worth saying that no words are really sufficient to describe the contribution the Irish aid workers are making in the midst of all the horror.

In Mogadishu North, the Red Cross and the Red Crescent work together in a former prison. Here a man holds lights over a horrifically wounded arm. A little boy is waiting for an operation on his leg. He makes signs to me that indicate he knows it is to be amputated. They are waiting for his mother to come and give permission for the amputation. His father is dead.

I still see that little boy, Ali, making his signs. Neither can I forget the haunting face of a dying child in Garissa. We made an attempt to rush him to the clinic. His mother had her dress stuffed in her mouth to stifle a scream. His father was weeping. Two other children were crying as they were led away. We didn't make it in time to save his life. The children of Somalia — I find it hard even now to write about them.

Something could be learned from all this. As we learned from Dachau and Auschwitz and fumbled towards a version of Human Rights; could we not take from Somalia an impulse to build food security in Africa, to prohibit the sale of armaments?

John Roche heads up the Red Cross operation in Northern Mogadishu. We attempt to visit the United Nations office together. We are invited in by a Norwegian Officer and an Egyptian Colonel. They are unarmed and a young teenager with a gun barely allows them to return to their own building. They are not allowed to bring us in. The sense of hopelessness deepens.

The youngsters with the guns are chewing quat [khat]; it is a narcotic which is chewed in the mouth and retained in a ball inside the cheek. When it secretes it gives a high and at about five in the afternoon its effects are obvious. By evening, however, as the young toters of kalashnikovs, bazookas, and rocket launchers on the backs of trucks, are coming down, the tension is palpable.

Crossing over to Mogadishu South, where Concern have their offices, the timing has to be exact and two separate teams of "technicals” from the Red Cross are involved. We get a puncture but we make it and visit Concern, who will bring us to Baidoa.

Passing through the dozens of improvised barriers on the road it becomes obvious that one is in a war zone. Yet, side by side with this, trading is going on. I remember again the scene near Mandera on the bank of the river that divides Somalia and Kenya, women and children carrying large boxes filled with sachets, curry powder, rexona — 'for a soft skin'.

As we arrive in Baidoa there is shooting. The International Red Cross warehouse is being looted. Everything is taken.

By the time I reach the town, the Irish media have begun arriving in preparation for President Mary Robinson’s visit. In the Concern house, I share a room with Vincent Browne, who will later deliver a fine piece on Africa in the Sunday Tribune. He has the better bed, protected by a mosquito net. The lumps that came up on my hands and legs tell me how practical such protection is!

It is in Baidoa that I see the hardest scene — the collection and burial of the dead in mass graves. At about 8am a single decker bus begins making its way around the collecting points. Occasionally, a body will be wrapped in a blanket. More usually, tied with several rags, they look like bundles of sticks. In a vast mountain of earth the gravediggers make the space. Several bodies, maybe 20, are placed in a single grave.

The relatives will not know where in this mountain of the dead their loved ones are buried. In Somalia in the past when a person was dying the neighbours stopped everything, dressed in white and through three days, called Tazia, they grieved. On the seventh day they ate camel or goat meat in celebration of the person's life.

Now the man laying the dead next to each other has sacking over each hand...

Talking to the UN's special representative to Somalia, Ambassador Mohamed Sahnoun from Algeria

In the airport in Mogadishu North, Ambassador Sahnoun is waiting for President Robinson. We talk for a while. Then news comes that the plane will be a little late.

Ambassador Sahnoun leaves. The plane comes in on time. David Andrews emerges to stretch his legs and suggests I have a word with the President. I have only time to wish her well, to thank her for her courage in deciding to come. Anything that can be done to draw international attention to the scale of the horror here is worth doing.

In the Horn of Africa there are 10 million “displaced" people, who will never be able to return home again. Poverty is increasing. Services are disintegrating. Aid is falling. And as Jack Finucane of Concern put it to me "the continent is awash with arms” .

There is hope that, through a Congress of the Elders, Somalian society can begin to be reconstructed. In such an assembly a legitimacy supported by tradition, however fragile, can be reconstructed. Such a Congress might prevail upon General Aideed and Mahdi to stand down, and thus to create a space in which peace might be established.

The UN will have to get a new, and far stronger Security Council resolution, and some armed force to protect its food operations — however risky the strategy — seems inevitable. “Every day here is like a year" said one Somali to me. There has been too much, culpable, immoral delay...

The Irish people, and the aid workers in particular, have shown outstanding generosity and solidarity with a stricken people. It is important that their interest be sustained. Our attitude to Africa over the next few years is one of the greatest moral challenges of Contemporary history.

Lasting peace will not come easily, however. As I finish writing, the news is bad. Concern are being forced to evacuate their staff from Baidoa, as General Morgan son-in-law of the ousted Siad Barre is approaching...

The Somalian people will have to suffer even more, if that were possible...

Watch President Michael D. Higgins' recent speech on the famine in the Horn of Africa below:

RELATED

- Opinion

- 17 Dec 25

The Year in Culture: That's Entertainment (And Politics)

- Opinion

- 16 Dec 25

The Irish language's rising profile: More than the cúpla focal?

- Opinion

- 13 Dec 25