- Opinion

- 11 Nov 20

The former State Pathologist talks Beyond The Tape, working on some of Ireland's most high profile cases, her UN experiences in Zagreb and Sierra Leone - and her love of Simple Minds, Adele and Madonna.

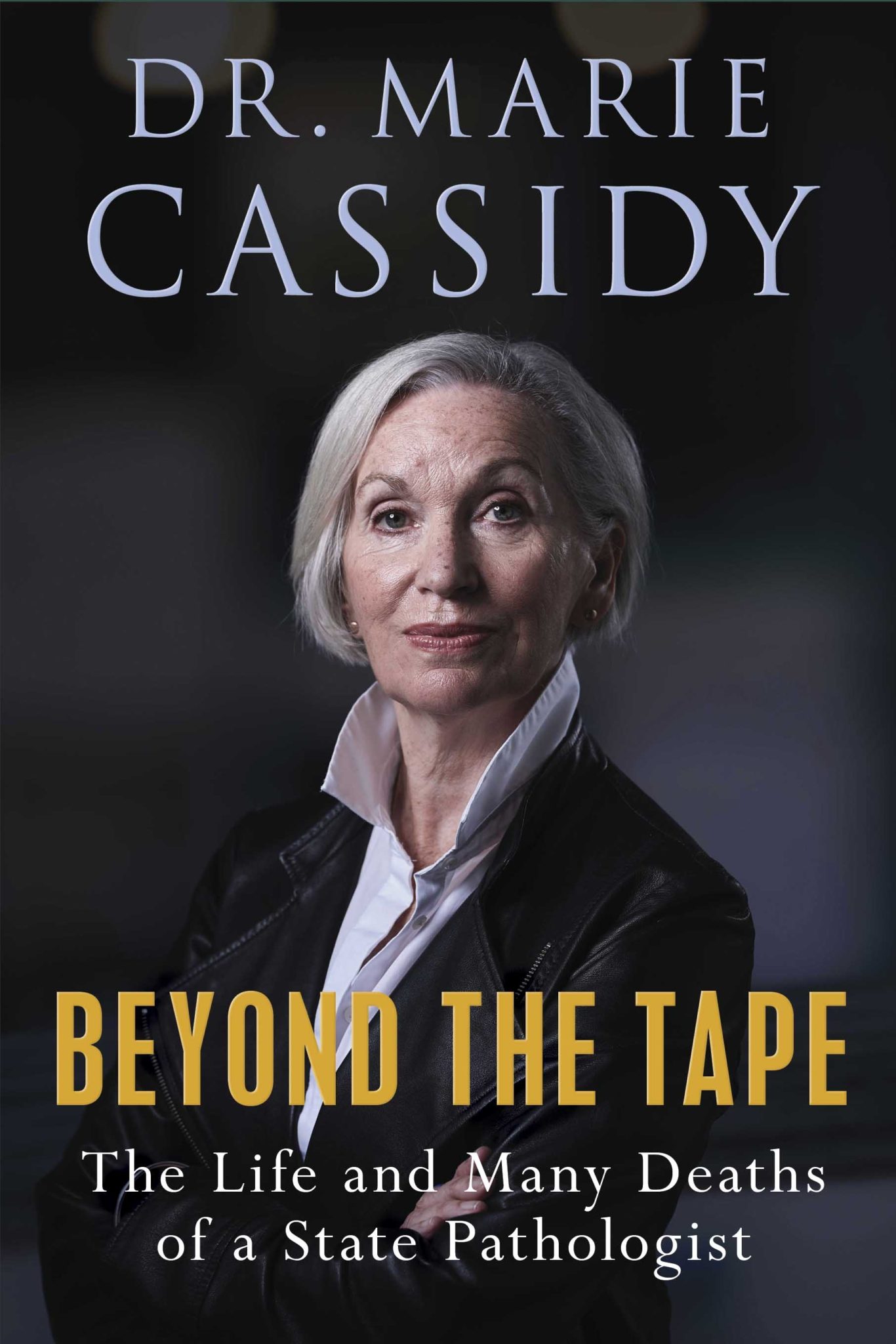

As Ireland's State Pathologist from 2004 to 2018, Dr Marie Cassidy worked on some of the country's most high profile cases, including the tragic deaths of Rachel O'Reilly, Robert Holohan and Siobhan Kearney. Cassidy's experiences are recounted in her brilliant and compelling new memoir, Beyond The Tape, which also reflects on her working class Glaswegian origins, her early medical career, and her time working with the UN in war zones in Zagreb and Sierra Leone.

Cassidy's sharp intelligence, as well as her warmth and sense of humour - she boasts a notably infectious laugh - were very much in evidence during her recent in-depth chat with Hot Press, which covered many aspects of a truly fascinating career.

PAUL NOLAN: What are you up to these days?

MARIE CASSIDY: Well, I had retired at the end of 2018, so I took a gap year, and it was during that time I wrote the book. After that, I was thinking, ‘What do I do? Where does my life go?’ And then we had this bloody pandemic, so I’m doing what everybody else is doing - which is nothing! (laughs)

You say in the book that you fell into the profession of forensic pathology. Looking back, are you surprised where you ended up?

I certainly didn’t start off thinking I’d be doing anything like that, but one door closes and then you manage to push your way through another one. That’s where things led me, and thank god they did, because I’ve had 30 fantastic years in forensic pathology. I’m sure I would have enjoyed myself in the hospitals, but you know sometimes you just discover something and you think, ‘This is what I was meant to do’? I think you’ll find all forensic pathologists are the same - forensic pathology finds you, you don’t find it.

What do you think you got out of forensic pathology that you mightn’t have got in other areas?

I just thought it was fascinating. It was one of those things - I don’t know if I’d have been as fulfilled in any other branch of medicine. I actually felt I was doing some good. It might not seem that way in that line of business, but I always felt whatever I was doing, I was a voice for the person who died. But more importantly, I was a person who might be able to get some information for the families and be able to allow them to come to terms with what had happened to their nearest and dearest.

Advertisement

I felt useful in that way rather than sitting looking at a microscope and going, ‘Yeah, they had appendicitis, I’m glad you took that appendix out.’ I just don’t think I would ever have had the same zest and get-up-and-go otherwise. Every morning I was bounding out of bed, because I just didn’t know what the day was going to bring.

What is the atmosphere like when you’re doing the job?

It’s the same as you walking into your office. You say to everybody ‘Morning, how’s everybody? How’s the wife? Did your kid get over the toothache? What did you watch on TV last night?’ It’s a place of work. Like yourself when you go into work, you’re professional in what you do. But that can’t define you - you can’t all be solemn all the time, and you don’t have to be solemn to be serious. We have to do it in a manner that means we can cope with it. And remember, we don’t know the person we’re going in to see, we’ve got no attachment to them. It’s very different to dealing with a death in your family.

I mean, I’m as bad as everybody else when it’s a death in my family. But I don’t know these people and I don’t know their background. And I don’t even know their family at that point - I don’t get to see their family until after everything’s done. I don’t see the effect that death would have had on them, so I’m not as emotionally attached as people who know them.

Do you think you need a particular temperament to do the job?

I think so. We all have to be a bit detached - the divorce rates in forensic pathology would tell you something about lack of attachment! (laughs). It’s all-consuming and your family does play second-fiddle, and they’ve got to be able to cope with knowing that somebody is disappearing off to see awful things. They’ll be back, but you never know when. You have to be able to cope with the things you see and deal with, and most of the people in forensic pathology are of that type.

Another fascinating aspect to your career is your work with UN agencies, identifying bodies and investigating possible war crimes in Zagreb in the mid-'90s. Your description of the trip is very stark - was that one of those experiences that does leave you shaken?

It was the scale of it. The difficulty with those kind of cases is that you’re not dealing with one at a time, you’re literally dealing with hundreds. The forensic pathologists who came out were a bit of a mixed bunch, they were coming from all over. I was working with Americans, Italians, Germans and people from all different countries. Some of them had English and some didn’t. The main language was going to be English and some of them had difficulties with that.

Because we were used to dealing with these kind of traumas, even if it was only one at a time, we could all kind of get on with it. But I did see the effect it had on other people had volunteered to be there. We had a lot of American students who’d come over, people in their twenties with humanitarian interests and all the rest. They weren’t prepared to be thrown into something like this, and you could see that it was taking its toll on them. A lot of the time we had to say to them, ‘You need to just go. You can’t do this, you have to leave here - this is bad for you.’

There’s also an amazing scene early in the book, where you talk about standing outside a makeshift mortuary in Sierra Leone, and seeing two vultures perched on the tree opposite you.

We were all on Lariam - as I say, we were happy as Lariam (laughs). I think the anti-malarials made us all psychotic! We were in this little bubble, the few of us who’d gone out there. But it was one of those surreal things. You were used to all the horrors that we deal with, but I’d never really thought about in any great philosophical way. When I was stood out there and seen these vultures, I thought, ‘Dear god - maybe this is grim! Maybe everyone else is right and I’m wrong.’

Advertisement

You would have been regularly mentioned in news reports on some of the biggest stories in Ireland over the past 15 years. Were you aware of being a public figure in that way?

You just ignore that. At first, I felt it was a bit intrusive and voyeuristic - the press appearing at everything and being so inveigled in it all. But then after a while, I got to realise, ‘Well, it’s part of the scene here, so just get used to it.’ And I’ve always been one of those people who thought, ‘The press have got a job to do as well. There’s a hunger to get information and they’re doing that.’ I never took any umbrage with somebody being there. I just thought, ‘They’ve got their thing to do and I’ve got mine - and they’re completely different.’

You discussed the Rachel O’Reilly case during your recent appearance on The Late Late Show. You mentioned seeing Joe O’Reilly appear on the Late Late in the middle of the investigation and thinking how suspicious he was.

Yeah! That side of the investigation has got nothing to do with me. I’ve got a very specific role, which is to determine the cause of death and give the Gardaí any information I can that will help them determine the circumstances of that death. But it’s not for me to say who did it and why they did it - clever people will be dealing with that.

But as someone who’s been in the business a long, long time, I’ve seen how people and families react to death in certain circumstances. And that to me was just the most bizarre reaction. And as I say, I must have been like everybody else in Ireland at the time, looking at him and going, ‘Jesus, I think he might have done it!’

You also discuss the very tragic case of Robert Holohan in the book. What are your recollections of working on it?

That was just a tragic case of literally a little boy - he was a tiny little thing. It was just one of those cases that captured everybody’s imagination. From my point of view, it was a difficult case, because everything was so subtle and there wasn’t any huge horror about it. That in itself is quite awful in a way - that a child could die without showing very much. People expect it to be, ‘Oh there was 20 stab wounds’, so they can go, ‘Oh that must have been awful, terrible’.

But when everything’s so subtle, you think, ‘My god, we really are quite fragile.’ We’re tough, but we’re fragile as well - something so fleeting can cause a death. All of us there were going, ‘Jesus, what happened to this wee soul?’ It was an extremely sad case, and it just got worse because of the length of time it took to find the body. The whole thing was horrendous, with the family having to deal with that. I was saying to somebody else, the people who you know and are closest to you are the ones who are more likely to hurt you in every sense.

You also discuss the Siobhan Kearney case in the book - which presented as a very difficult scenario for you to figure out.

Most of the stuff I do is pretty straightforward, it’s not rocket science by any stretch of the imagination, except no one else wants to do it, which is fine. Though it is causing a problem right now in Ireland, because they can’t find anybody else to do it - there aren’t too many mad people out there like me. But sometimes you come across a case which could go any way - it could be a suicide, or a tragic accident.

It amazes me, though, how often the people who work in my industry - from the guards all the way through to the scientists - there’s something in the back of our minds that goes, 'There’s something not quite right here'. You walk into something and go, ‘Oh, this wasn’t what I expected from what you said this should be.’ And sometimes we get to the end of it and we go, ‘Well, it is what it is, it probably is okay.’

Advertisement

And other times, like Siobhan, we go, ‘No, no, no - this isn’t right at all. We need to throw everything we can at it.’ That’s where the team work comes in, because everybody then pitches in and gives their sixpence worth. Hopefully you get some kind of answer at the end of it.

How did you unwind from the job? Were you a big reader or TV watcher?

Oh yeah, I’m an avid reader - I read all the crime novelists. Everyone looks at me and goes, “You’re really reading that?’ And I go, ‘Yeah, I think they’re good fun. I sometimes get ideas out of them - you never know!’ I just watch nonsense on the TV, because sometimes I’d get back at 2 or 3 in the morning and everyone would be in bed. I’d have the TV down low and I’d be watching any nonsense I could find, just to clear the head.

You mention in the book working as a consultant on Taggart. What do you think are the best crime films?

Do you know, I’m very squeamish! I can’t watch any violent films at all. I can do my job because I’m presented with something when it’s all over. There’s no pain, no suffering - there’s somebody dead and I need to find out what happened to them. But to watch things... I’m the one that’s going, ‘Oh dear god!’ Although I read a lot of crime fiction, I don’t actually watch a lot. The graphic scenes are just too much for me.

Funnily enough, my recent reading matter has been your book and Thomas Harris’s Hannibal Lecter omnibus!

Well, everybody has to have seen The Silence Of The Lambs! (Laughs) I thought it was a good film and that was about it. Thankfully I’ve never come across him or anybody like him!

Are you a music fan?

I listen to anything and everything. I go through phases - I mean I come from the pop era, I’m of that age. And I love a female diva. It’s only in the last five years that I haven’t really kept up with new artists. Up until then, my kids were at home, and I used to just give my son my iPod and say, ‘Just download anything.’ He’s got quite an eclectic taste and I used to be quite happy with that. Now that I don’t have that link with them, I’m not up to date with a lot of the modern stuff.

When you say female divas - are we talking Madonna?

Oh yeah, Madonna, Adele, you name it. All these strong women singers, I’m there. Whitney, Mariah Carey - I love a good diva.

Did you ever go to gigs?

Yeah, but it was always the old-fashioned ones. I think the last one I went to was Simple Minds.

Advertisement

Did you have an affinity with them, being Scottish?

In a way, yes. I was kind of brought up on them, and I think they’ve weathered quite well. I think it was only two years ago I went to see them. That was in the Olympia and it was absolutely fabulous.

I’d say you were a New Gold Dream era Simple Minds fan.

Yeah - that was me!

- Beyond The Tape is out now, published by Hachette.