- Culture

- 21 Oct 22

Graham Coxon: "I didn’t quite know how big we were gonna get. I didn’t really know if I wanted to be big"

With his cracking new memoir Verse, Chorus, Monster! on bookshelves, legendary Blur guitarist Graham Coxon talks iconic songs, Britpop adventures, drinking, anxiety, ’90s feuds and Damien Hirst. Oh – and the possibility of a one-off Blur-Nirvana supergroup!

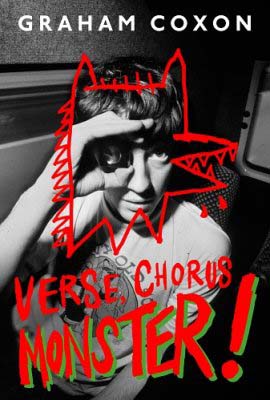

Verse, Chorus, Monster!, the new memoir from Blur guitarist Graham Coxon, compellingly documents his fascinating life story, from his upbringing in England and Germany where his father was stationed with the British Army; to meeting future bandmate Damon Albarn in secondary school in Colchester, Essex; forming Blur at Goldsmiths art college, where he befriended bassist Alex James and hung out with the likes of Damien Hirst; fame and fortune during the Britpop era; and his departure from Blur in 2002, before their eventual reconciliation for a triumphant comeback tour seven years later.

Though the book contains plenty of funny moments thanks to Coxon’s absurdist sense of humour, as with any life story, there are some tumultuous periods too, which the 53-year-old bravely dives into. His split from Blur in ’02 was preceded by a period of heavy drinking that ended with a stint in rehab. Eventually going teetotal, Coxon – prone to anxiety throughout his life – reveals in the book that he secretively began drinking again during the band’s ’09’s reunion tour, once more forcing him to confront the problem.

In a scenario many will recognise, stresses brought on by lockdown in 2020 led to Coxon splitting from his partner and young child in Los Angeles, and returning to London. He describes the painful experience of quarantining on his own in LA, before boarding the plane to England, unsure of where he’s going to live upon returning to London (eventually, his management secure him somewhere to stay).

Following Blur’s well received 2015 album The Magic Whip, the tour for which included a headlining performance at Electric Picnic, Coxon has mainly focused on soundtrack work, including cult Netflix hit The End Of The F*****g World. This was the starting point of our discussion, when I recently caught up with the guitarist over Zoom at his London home.

PAUL NOLAN: The last time I spoke to you was in 2018, when the End Of The F*****g World soundtrack was released. Could you have imagined that four years later, you’d have written your autobiography?

GRAHAM COXON: The last four years have been totally insane, especially the last two. I wouldn’t have imagined how much things have changed since 2018, no. I mean, things changed so much for me that it seems barely possible.

Was Verse, Chorus, Monster! born out of lockdown?

Not really, I’d been working up to it for quite a while with Faber. I thought maybe I’d do a book with art in it, etchings and all the rest. Then it kind of went to sleep for a bit, before we renewed the concept. We made it more like a memoir, but an art-heavy one. Alex had already done a book where he talked a lot about what Blur got up to.

I went through Essex for the first time last year, on the way to the Latitude festival in Suffolk, where Damon was actually playing. How do you think growing up there influenced Blur?

I really wasn’t brought up in Essex – I was brought up in Germany, Derby and then Essex. But what did I have in Derby that I wouldn’t have had in Essex? Maybe more countryside. In Essex, I was in a town, and there was a lot of wandering around the old Roman roads and that kind of thing. But apart from that, it’s normal kid’s stuff. Wherever I found myself externally, my internal world was always going to be very far removed.

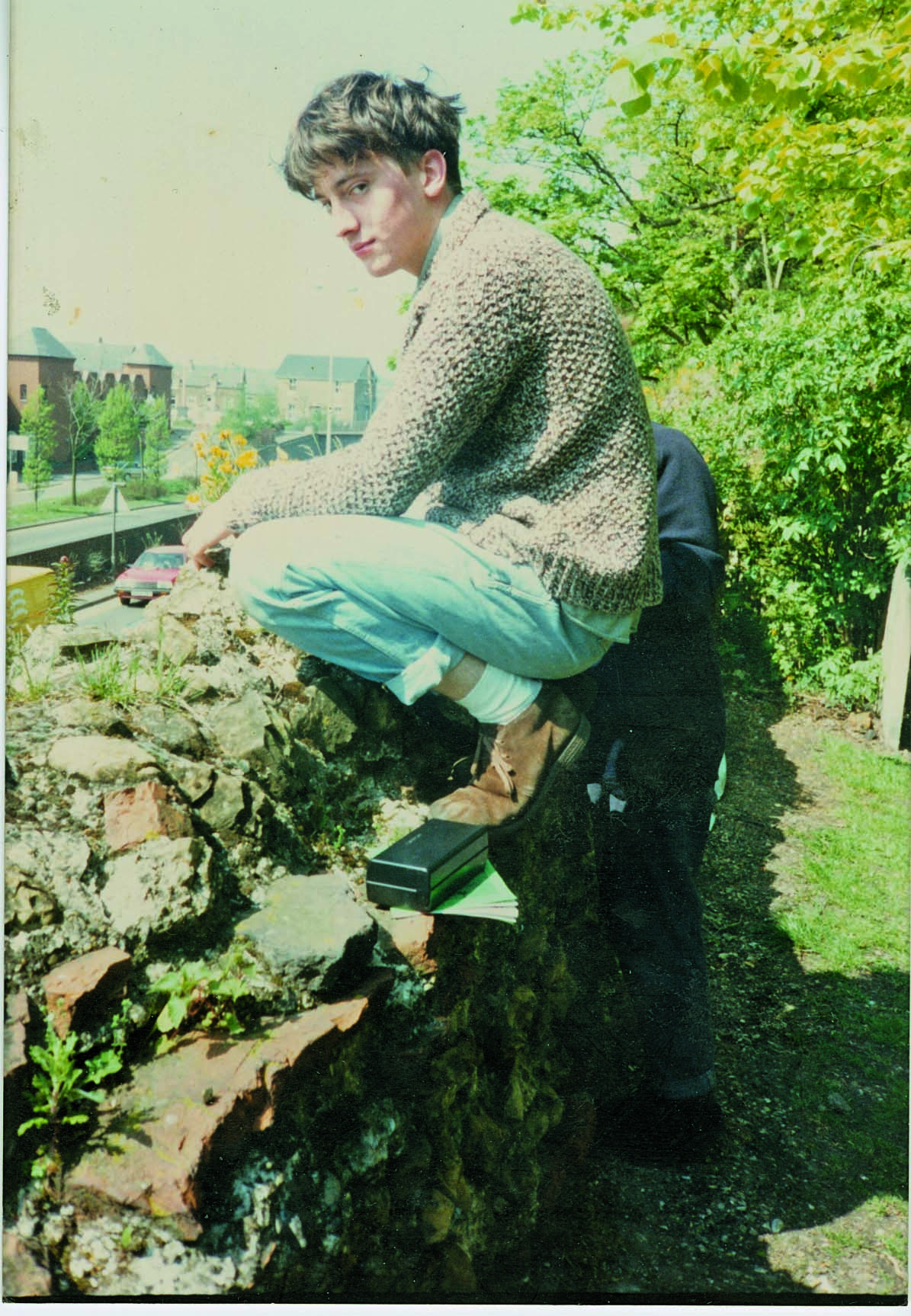

Courtesy of the author. Photo by Sue Harper

You probably would have ended up doing music and art wherever you were brought up.

I think so. When my dad came out of the army, there was a big chance we could have settled in Derby – they looked at a house there. So, I could very easily have grown up there and not met Damon. Maybe I could have been in a band like Cable! It was pretty close. So I could have not met Damon, or not gone to Goldsmiths and met Alex. It’s ridiculous how life works.

Where you thinking about an art career when you went to Goldsmiths?

I wasn’t really intent on a career in anything. I was useless! I lived for whatever was gonna happen in that day, and as long as there was a couple of drinks at some point, I was alright. Goldsmiths was hard, it was suddenly serious. It was like, ‘Oh flip, I’m amongst people who are really serious about what they do.’ I came from an art school in Colchester where I was one of the most serious about art, to somewhere people were actually churning out stuff. With the conceptual artwork and so on, I felt slightly out of my depth.

But you persevered.

I knew I had to go to London, because that’s where Damon was. We wanted to carry on doing musical stuff together. I picked Goldsmiths and my tutors at the Colchester art school were like, ‘Really? Well good luck! If you don’t get in, you’re going to Scunthorpe.’ But luckily I got in and that was a relief. There’s been a lot of strokes of luck.

From the book, it seems like you weren’t the biggest fan of the more conceptual art being made by your Goldsmiths contemporaries, such as Damien Hirst.

No, I liked it. It just didn’t seem like I was very capable of it. I thought it was cool. But it was far removed from what I was doing. I was a bit childlike and figurative and I had to learn about what things mean; what I wanted red to mean, and what I wanted some shapes to mean. Eventually, I did go more into abstract and conceptual stuff – I did some sculpture and paintings that were a little more in the realm of the New York school. Abstract art is a different thing, it really is about shapes, colour, composition and balance. But I get a huge kick when I see a decent piece of work like that.

How did this all feed into your music?

It’s a confusing thing for me. It was never like I saw myself in an art career, it was almost like I liked too much of it. It would have been much better if I just liked Barnett Newman and hated everything else. But as it was, I liked Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell and Willem de Kooning just as much as I liked Picasso and Modigliani. I thought all that stuff was great, but I didn’t quite know what to do with it all.

Did you have a clearer vision with music?

With guitar, it’s different. You can love a bit of The Beatles, King Crimson, Sly and the Family Stone, Nick Drake, Joni Mitchell and Kate Bush. You can get the guitar in amongst that stuff. Although when I listen to jazz, I really switch into saxophone mode a lot more. But I felt I had a lot more agency within music. At the time, I still couldn’t play that well, but I could get parts that were right for the songs.

In the world of music, I felt I could gather everything together, because really it’s about harmonics, chords and structures. Art is different; you can’t do something that’s Franz Kline and then have an Edvard Munch-type figure in the middle of it. You can’t mix it up as much, there’s no wit in doing that particularly. Do you know what I mean?

Absolutely.

There’s a wit in the personality I have within music, where I can convert, say, ’50s ideas into a different context. A bit like The Beatles did – they were kind of punk rock Roy Orbison at the start.

Ten years ago, I saw the gig Blur did in Hyde Park to mark the end of the Olympics. The following day, I went to see a Damien Hirst retrospective at the Tate, which I thought was brilliant. How well did you know him in college?

I saw him a lot. And also Abigail Lane and Michael Landy – they were the people I was hanging out with. My friend Adam Peacock had gone to Goldsmiths a couple of years before. When I got there, he was in the third year and they were all his friends. So I was hanging out with them before I made friends in my year.

I got involved with doing performance-art videos with Adam and his creative partner. I saw all of those people getting their shit together. I remember seeing Damien’s degree show. I think it was the medicine cabinets that were named after Sex Pistols songs, ‘Bodies’, ‘No Feelings’ and so on. Blur played at that degree show. I was aware of them, definitely. When I got there, Sam Taylor-Wood was in the year above me.

You talked about not really having a plan when you got to college, but Damon was always very driven. Even still, were you surprised at how huge Blur became?

I was quite shocked. I think I knew what good music was and I liked what we were doing. They were good songs, but I liked that they had some lunacy in there. With the early stuff, a middle eight would suddenly go twice the speed, and be all abstract and daft. It was a little artier and a bit more like Stutter, the first James album, which is a crazy little LP. There was some interesting stuff on that.

What did you think of the musical landscape at the time?

It was very different right at the end of the ’80s, bands weren’t all being baggy and Madchester; there was a lot more interesting stuff going on. But I didn’t quite know how big we were gonna get. I didn’t really know if I wanted to be big. What I liked at that time was Dinosaur Jr and My Bloody Valentine. It wasn’t like I envisioned getting bigger than that, but Damon definitely did! And that’s a good thing – he had total belief and agency, as a person and as a leader of the band. He was very serious about it.

Did you feel there was good chemistry between the four of you from the start?

Yeah, definitely. There’d been a few line-ups. Damon had been working with some other people, who I think he knew from his acting school, East 15. They were making music and I’d occasionally travel up to London to play in it. Damon and I had a couple of late nights at this studio where he was working, really just simplifying things with a drum machine, until we were doing almost Velvet Underground-type stuff. That made the guitar and rhythm more prominent, and simplified the chord sequences.

Then Alex and Dave entered the equation.

Dave was always the drummer in that band. I think what happened was, the two guys Damon was working with didn’t really like the new musical direction. They decided to go off and do their own thing, so we hadn’t a bass player. I said, ‘Well, Alex lives below me at college, why don’t we get him in?’ It was very easy. Probably the first time we got together, we wrote ‘She’s So High’. It came out of a jam session I have the cassette recording of, which I think came out on a boxset at some point. It was pretty instant.

Blur

BlurIn the ’90s, bands slagged each off in the music press and there were a lot of rivalries.

It was strange, people did slag each other off within the British groups. I always thought, ‘Fuck, we’re all striving to do the same thing. We all probably like the same bands and yet we’re all slagging each other off!’ But it was a matter of life and death for our careers at that point. And we were competitive young men, mostly, I suppose. So that’s how it was. But I find the constant encouragement these days a little bit sickening. Maybe that’s cos I had it so hard in the ’90s. Now everyone’s so nice to each other I want to puke.

Last year, I interviewed James Dean Bradfield from the Manic Street Preachers, who were kings of the withering putdown in the ’90s. I think it’s a very Gen X perspective – we like things a bit tougher.

We didn’t know about anything. All we had in those days was someone telling you, ‘Don’t be a fucking idiot’ and giving you a kick up the arse. Now, you get support and everybody knows about anxiety and mental health issues. You didn’t have that then. It was like, ‘Oh come on, buck the fuck up. Are you gonna do this or not?’ It was pretty tough love.

You talk very honestly in the book about your drinking, and how you’d quietly started again when Blur reformed in 2009. Was that a very private thing you were doing at the time?

I fell for the oldest trick in the book with alcoholism – it was people, places and things. And also being kind of anxious and scared. It was such a massive trigger when I went back to rehearse with Blur again in 2009. I was not in control, almost. I went home after one of the first rehearsals, and walked straight past my road to the pub.

It was almost like I didn’t have any way of controlling it. It was a beautiful day, the rehearsal was great, everyone was cool. And I thought, ‘Well, that calls for a glass of wine and a cigarette.’ That was it, I didn’t really think much about it. But I didn’t really go over the top. I might sneak a bottle of Becks from the dressing room (laughs).

When everyone was going to the bathroom before the show, I’d go in the portaloo and have a beer, then go onstage. It was like it always was, it just knocked the edges off my anxiety. Because they were kind of scary shows.

Hot Press Vol 33 No 13 July 15 2009

I went to a number of those shows, and any unease you might have been feeling definitely didn’t come through in the gigs. The performances were always immaculate.

I suppose we don’t rely on a lot of technology. We rely on a lot of muscle memory and we rehearse a lot. The songs aren’t massively complicated. I mean, I do have a tough job, granted. I’ve got a lot of noises to make, a lot of foot-tapping to do on pedals, as well as backing vocals. And then trying to jump up and down a bit.

It’s tricky, but I am obsessed with it. That has been my job: the transitions between sounds and my backing vocals, it has to be very smooth. Unnoticeable, almost. That’s what I work on. But after a bit, that becomes like driving a car. After a few weeks of rehearsal, your foot just does it. They’re our songs, we’re good at playing them.

It’s a comfortable space. But I like fucking up. I used to mess up a lot more when I did acoustic shows, which were far more frightening because it was just me and an acoustic guitar. The thing is, I would have some kind of a disclaimer, which you can’t do at those huge Blur shows. At those tiny solo gigs, it was like, ‘I’m not gonna look at this as a professional show. I might mess up, let’s keep it casual, let’s have a chat.’ That gets rid of the pressure. And if I mess up, the audience kind of like it and we have a laugh about it, and we start again. It’s not the end of the world, really.

Whenever I’ve talked you before, I always meant to ask about the look of Blur. Was that something Damon decided on before each album?

I don’t know what the changes of look were. I suppose it went from baggy, to mod, then back to baggy again, didn’t it?! (laughs). The thing is, we were scruffy fuckers, really. I’ve been realising that recently, when I go to see groups now, and they’re wearing really nicwe suits and looking chic. We were just wearing some work clothes that we were comfortable in. A pair of Vans or desert boots, some jeans and a t-shirt. Damon would go to the box of Fred Perry t-shirts in the corner of the dressing room, and pick one out and put it on. I don’t know if we changed our look that much, did we?

Well, definitely there was a transition from a mod aesthetic during Britpop, to more of an American slacker look in the late ’90s, inspired by the likes of Beck, Pavement and Sonic Youth.

I suppose that was just because of what was around clothes-wise. I think Damon was wearing Maharishi trousers a lot, and I was starting to wear Stussy stuff cos I was skateboarding around. But I don’t think Alex and Dave changed an awful lot. I mean, Alex never really gave much of a shit about clothes. Dave would wear a Fred Perry, jeans and a pair of DMs. I suppose Damon and I shifted around a bit, but I’ve always been jeans and a stripy t-shirt. I guess I would wear Grand Royal and Stussy t-shirts a little bit, and skate shoes. Not very chic. It wasn’t really reinvention, I suppose we automatically adjusted when we saw what Damon was wearing.

Blur and Nirvana are my favourite bands. I actually interviewed Dave Grohl earlier in the year as well – so I was wondering, what are the chances of you forming a one-off supergroup to play my birthday?!

I’d be well into playing with Dave, a fantastic drummer and guitar player. It’d be interesting to hear what ‘Song 2’ sounds like in that set-up.

It’d blow people’s heads off.

(Laughs) It would, yeah!

Is there going to be another Blur album?

Oh, probably. I don’t know when, though. I imagine there will be – it might be in five years’ time or something!

• Verse, Chorus, Monster! is published by Faber & Faber.

RELATED

- Culture

- 14 Jul 23

Damon Albarn starts work on new opera project

- Culture

- 11 Jul 23

New BBC podcast explores rise and fall of Britpop

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 06 Jul 23

In the new issue: Blur, Christy Dignam and the Irish Women's World Cup squad star in our Triple Cover Special

RELATED

- Culture

- 18 May 23