- Culture

- 24 Sep 19

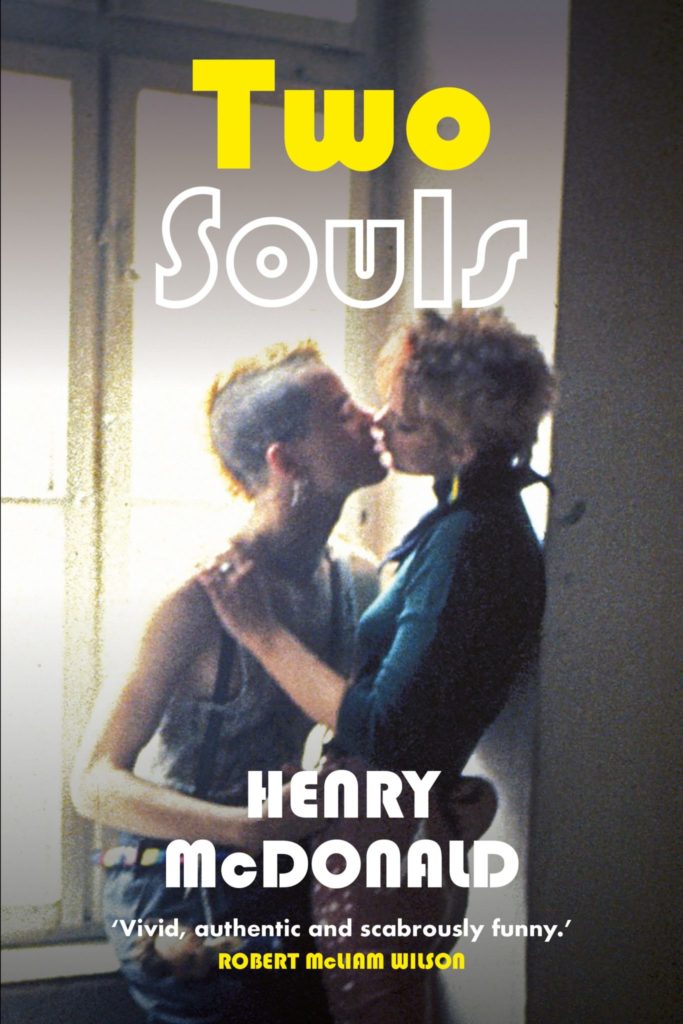

Author of the Troubles-themed Two Souls, Henry McDonald talks punk rock, football hooliganism, paramilitaries, being kidnapped by the New IRA, Brexit and more. Photography by Bobbie Hanvey.

Two Souls was rattling around in Henry McDonald’s head, ever since the ceasefires were called all the way back in 1994. Like much of the turmoil over the course of 25 years which led up to that moment, his novel is about dividing lines.

There’s the obvious ones. The opposing sides in the 1979 Irish Cup Final, where most of the novel’s action takes place. The two groups of supporters who face-off against each other in the stands – the largely Catholic fanbase of Cliftonville and the Protestant-aligned Portadown-ers. The two sides of David Bowie’s Low album, which soundtracks the protagonist Robbie McManus’ doomed love affair with the mysterious, radiant Sabine.

Then there’s the less obvious dividing lines, characterised as the ‘two souls’ which fight for control over an individual: the side which chooses patience, pacifism, love; and the one which gives-in to hatred. As Henry’s novel explores, for those growing up in a theatre of war, giving-in to hatred could often involve life-changing decisions.

“Anyone could’ve been sucked in,” says Henry, who grew up in Belfast in the midst of the Troubles. “The violence was very seductive. For a lot of people – it was a juncture. Every person faces these junctures in their lives, but the difference is that where we came from, the direction you chose could be a matter of life or death.”

The ceasefires were a turning point in Ireland politically, but for those who had been on the ground throughout the violence and turmoil, it led to moments of intense self-reflection.

Advertisement

“It made me think back to the ’70s and ’80s and what it was all about,” Henry explains. “The story started whirring in my brain. The thing that I always wanted was for this book to be more universal than just about Belfast and the Troubles. I’m fascinated by how sexual jealousy and sexual frustration can lead people towards violence. There’s a solidarity in violence for a lot of people, a comfort in it. Seriously, it was like the certainty of violence could become a comfort blanket.”

Two Souls is told in flashes. It follows several key moments across 16 years, as a group of teenagers in Belfast shift their sense of identity from diehard punks with lofty ideas about love, to raucous football hooligans dabbling in drugs, vice and revenge, to – eventually – their roles as high-ranking paramilitaries. There’s no simplistic political propaganda here. Rather, Henry spills complicated, flawed characters onto the page. He calls writing the book an “exorcism”.

“It isn’t autobiographical,” he attests, “but it’s based on the experiences I went through in the ’70s and the ’80s, and the people who I grew up with. In school and where I lived, a lot of people either went to Milltown cemetery or the Maze prison because of choices they made. So this was based on raw experience – but distilled and worked on.” “Raw” is the key word for Two Souls. The novel strips back any rose-tinted notions about ‘the struggle’ and gets into the gritty, conflicting reasons why people embraced hatred.

“I’m fascinated by the idea of two selves,” he says. “I had this epiphany about 40 years ago. On school days, I used to get the bus to St. Malachy’s when it was too cold to walk, and I’d talk to this guy called Gaudy, who went to Boys Royal Academy. We’d talk about bands and who we liked, who we didn’t. I used to see him in town at the record shops as well.

“Then I remember being at a Cliftonville game and there was a load of young Glentoran fans howling sectarian abuse at us through the segregated fence – and there was Gaudy leading them, screaming ‘You dirty Fenians’! I remember he looked at me, clocked who I was, and turned away like he was embarrassed. Truth be told I was probably screaming the same shite at him. But that moment of recognition always stuck with me. We were all living double-lives. That was one of the origins of this book.”

In recent years, there’s been a wave of revisionism on the part of political parties and commentators about the Troubles. Literature has arguably been far better at getting to the complexity of the conflict. Interestingly, Henry sees the same thing going on with Brexit, dissidents, and the border. He believes that fears of a return to the conflict are greatly exaggerated.

Advertisement

“Some of the shite being said at the minute about Brexit and the border is ridiculous, mainly by ‘singing for their supper’ journalists in Dublin, who tour London newsrooms with their messages of doom and gloom. They’re the new rewriters of history.

“The historian Ed Moloney – someone who I highly respect – said that up to 30% of the IRA were infiltrated by the various branches of the British security forces during the Troubles. So you ask yourself – what’s it going to be like for the dissidents? Given not only the money spent on defeating them, but the technological innovations in the last 25 years. Who are the only people they killed this year? Lyra McKee – who was a friend of mine. But the point is, the dissidents can go on and on about Brexit and how it’s giving them a boost, but they’re not a threat like the PIRA were. People are dishonestly ramping up the Brexit effect, saying ‘We’re going back to war’. No, we’re fucking not. It’s insulting. I find some journalists the worst offenders.”

In the past you might have had crime writers coming to Northern Ireland to pen their bestselling thrillers. Now, you have foreign media coming over to get their stories from the ‘frontlines’ of the border. Is there a fetishisation of the division in the North?

“I don’t even mind the fetishisation of it,” he says. “What really gets me is the hyperbole, often for a cause that has nothing to do with Northern Ireland. And I do think that it’s mainly people who are anti-Brexit who are deliberately hyping up the efficacy of these groups like the New IRA, to make political, partisan points. It’s always a self-fulfilling prophecy – the more they say it, the more the eejits in the dissidents will think, ‘Let’s do it.’ But I do find it nauseating, some of the people who were great critics of Brussels, beating the drums of doom over Brexit.”

Henry was the first person to be given a statement by the ‘New IRA’, when they kidnapped him in Derry…

“I was told to turn up at a hotel by the Bogside,” he begins. “I was heading towards it and this very fancy car screeched up. I was driven for ages, I assume west across the border. Then the car came to a halt on this country road. I kept thinking of all the people over the last 25/30 years who’d been driven out like this with binbags over their head, who’d then been shot.

“Then another car pulls up, and this guy gets out with a written statement and he tells me to take it down. I take out my notebook and write the statement down. It’s basically the New IRA announcing their existence. As soon as I’d written it, the guy burns his statement and drives off again. Then half an hour later, another car arrives and drives me back to the Bogside. Very strange, very bizarre, almost comedic.” Having quite literally gone through the wars to come out the other end with this book, you can be absolutely assured that Two Souls is the real thing…

Advertisement

• Two Souls is out now, published by Merrion Press.