- Culture

- 02 May 22

Interview: Colm Tóibín - The Master And The Magician

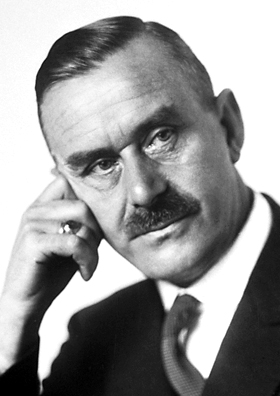

Revered as one of Ireland’s greatest writers, Colm Tóibín’s latest novel – The Magician – examines the life of German literary superstar, Thomas Mann. Here, the recently appointed Laureate for Irish Fiction discusses growing up as a gay man in pre-Same Sex Marriage Ireland, how the contemporary world would view the sexual obsession with an adolescent male that’s at the heart of Mann’s 1912 Death In Venice classic, the best way of reading Ulysses – and his own battle with cancer.

The latest work of Colm Tóibín, the man who gave us Brooklyn, filtered and filled out Aeschylus with House Of Names, and took us into the minds of Henry James and the Virgin Mary, reimagines the life story of the renowned German Nobel-prize winning author, Thomas Mann.

The Magician is among eight books that have been shortlisted for the Rathbones Folio Prize for Literature – alongside The Promise by Damon Galgut, My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley and Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, among other outstanding works of contemporary fiction.

Colm is sitting in a sunlit room in Los Angeles as we speak. I enquire after the mood in America, given the storms over Europe.

“There are funny myths, almost foundation myths, built deep into the psyche here,” Colm reflects. “One is fear of the Russians since the end of the Second World War. The other big issues are the price of gas and inflation. The price of gas here is extraordinarily low – and everything depends on that. In LA, everyone can drive around all day without worrying, because it’s cheap. Cheap gas is an essential element in how this country works. If that started to slip, it would be a very serious matter.”

A Guest At The Feast

Colm Tóibín’s successes are manifold. His debut novel The South (1990) was well received, but the follow-up, The Heather Blazing (1992) set the bar higher again, winning him the Encore Award. In case anyone thought that was a fluke, The Blackwater Ship (1999) was shortlisted for both the Booker Prize and the International Dublin Literary Award, and The Master (2004), in addition to being shortlisted for the Booker Prize, was the Los Angeles Times Novel of the Year, and won the Stonewall Book of the Year and the Lambada Literary Award.

We could be here all day listing awards and nominations – his 2009 novel Brooklyn, for example, took home a few gongs before being turned into a very successful, award-winning movie starring Saoirse Ronan – but he increasingly finds himself receiving what might be called Lifetime Achievement Awards, the most recent being The David Cohen Prize for Literature in 2021. He was also recently named as the Laureate for Irish Fiction, 2022-2024.

“As Anne Enright said, as the first laureate, it’s both an honour and a job,” he smiles. “You take both of those things seriously. I’ll be sixty-seven in May and I’ve published twelve works of fiction, so it’s nice to get some sort of recognition in your own country. It’s certainly better than being banned or censored or ignored."

“It isn’t just a lecture each year,” he adds. “I’m doing a blog every month for the Arts Council website, and over the three years, we’ll probably end up with thirty-five books we’ll choose in partnership with libraries. People, especially coming out of the pandemic, spend a lot of time reading. We want to offer a platform where reading can be filtered and shared.”

Have you some criteria for selecting the books for The Art Of Reading, the monthly book club?

"I do and I suppose it's personal. The second one was Esther Waters by George Moore, a novel that should be better known. A lot of people were really surprised by how good it is. Clare Keegan's book, Small Things Like These, had a special place in society over Christmas, so I thought, let's start with that. There’s no committee involved, just things I'm reading and thinking about. I was made laureate so it's my taste and interests, which are pretty broad. There isn’t a certain sort of writer I really like, I'm not going for a single style or anything like that. It's to give readers a forum. No one really wants to read alone."

We're still a nation of readers then?

"Books take up a lot of space in people's minds in Ireland, and there's a funny way that a new book can create an excitement. We’re going through a particularly rich time at the moment, a lot of new stuff coming out, a lot of first novels."

Do you make it your business to stay abreast of what's going on in Irish writing?

“I’ve just come off doing a zoom thing for Faber with Audrey Magee, whose new novel The Colony has just come out,” he says. “And next month, I think, we’re doing Colin Barrett’s new book of stories, Homesick. I’m a reader. Like a lot of people I bought Colin Barrett’s first book Young Skins because people were talking about it. I read Kevin Barry in the same way. These books were in the air.”

The Use Of Reason

A recent post on his Arts Council blog concerned the list of attendees at Robert Emmet’s execution, as listed in the Cyclops episode of Joyce’s Ulysses. Specific mention was made of one Borus Hupinkoff, who Joyce tried to add when the book was at the printers, but to no avail. Borus finally got in when Hans Walter Gabler constructed a new edition in the 1980s.

“It’s a marvellous story, isn’t it? I was signing books and a friend of his said, ‘This is for Hans Walter Gabler’, so I signed it Borus Hupinkoff. I’ve been in touch with him a few times in the last few months, and I always ask after Borus. It is one of the most extraordinary little details, poor Borus wandering from 1922 to 1986.”

In Ulysses: A Reader’s Odyssey Daniel Mulhall offers a roadmap for those who might be a tad daunted by the big book; you can skip over the difficult bits and then come back to them.

“I am implacably opposed to that,” Colm says. “I think that is a horrible mistake. My idea is that you read the book as eighteen episodes. Stop worrying, just finish the episode. The problem is when you come to episode three, it is a roadblock, but if you don’t read it, you missed the whole business of what Stephen is doing, his mind finding poetic images for everything, he won’t leave a word alone. He knows too much, he’s read too many books – but you have to follow him to get to the wonderful opening of episode four with the very precise, exact description of a man having breakfast while his wife is in bed, and no books are mentioned."

“In order to savour four you have to have read three, it’s counterpoint. You exaggerate and exhaust a style and the next chapter starts something entirely new. It’s almost like saying if you have problems with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, just listen to the end. I don’t think so. I can see what Daniel Mulhall means, but I think what he’s saying is fundamentally flawed. He’s a diplomat, and I’m not!”

It’s at the start of episode three that a lot of people might put it back on the shelf and think ‘I’ll have another go later’.

“Go to something like Terrence Killeen’s book [Ulysses Unbound],” he advises, “which will give you the when, where, how and why, and then move slowly. There’s no reason to read this book quickly. Take your time. There’s a later episode called Oxen of the Sun, which you really need to work on, but if you go into the next episode, without having read it, you’ve missed the point. That’s my argument. No, no, no!”

He adds a final, loud ‘NO’ for emphasis.

Declan Kiberd's Ulysses And Us: The Art Of Everyday Living is another useful one.

"His book is one of the helpful ones. While it’s filled with ideas, it does actually take you through episode by episode. Read as much commentary as possible, because some of the commentary is tremendously good. And it isn't as though they're all these critics who killed James Joyce, they will really help you to see. But there's still things that no scholar has found. About three years ago, I'm not making this up, I was reading the Cyclops episode, and it's in the Robert Emmet execution parody. He names the executioner Tomkin-Maxwell ffrenchmullan Tomlinson. We don't know who Tomlin was, and everyone says we don't know who Maxwell was, but by God, I thought, I do! Maxwell was Sir John Maxwell who ordered the executions of 1916."

Which hadn't happened yet.

Yes, Cyclops was written after the 1916 Rebellion but set in 1904. And this is a little clue. I actually called a friend of mine who's a big figure in the Joyce world and it seemed that no one had noticed it. I think the main thing about Ulysses is it gives infinite pleasure. I came to it late and it's brightened up my days."

Men Without Women

There’s a story about Colm, as a young man, working in a bar in Tramore at night, and lying on the beach, reading The Essential Hemingway, by day. What was it that hit him so hard; the content, the style?

“I wasn’t aware of either content or style – I wouldn’t have had those words at my disposal – but whatever it was, took me over. It was interesting that I had nothing in common with it – it wasn’t as if I was reading A Portrait of the Artist or Frank O’Connor, about Irish childhood and Catholicism. There was nothing recognisable to me, and yet I was completely engaged. It was really exciting.”

Why write a book about Thomas Mann – or Henry James – rather than Hemingway?

“The question of disentangling Hemingway’s secret erotic life would be very difficult. He may have written about heterosexuality but what really interested him was the ambiguous spaces in sexuality. And there’s no great mystery about other things around Hemingway. There was a pettiness in the way he dealt with publishers, writers, and women. I have no interest in all of that. Therefore, there’s nothing I can add to his story or our sense of him. I feel the same about Lorca or Joyce, their sexuality is so clear. I’m interested in things that are not clear and certainly Mann is not clear.”

Were Mann and Henry James important to you growing up because homosexuality was unmentionable.

“It’s more that I read those big books aged between about eighteen and twenty-two – most of James and most of Thomas Mann. And I thought then that books were written by people out of certainty, ambition, entitlement, a sort of natural ascent to power. Graham Greene became Graham Greene because he was confident, ready, and certain. In the case of both James and Mann, you learned a lot later on, as more and more biographers and diaries and letters appeared. In the case of Mann, the diaries showed what a shivering, strange, uneasy figure he was, and how the books came out of uncertainty and unresolved experience. This was a big revelation for me: you realise that it’s unresolved experience that nourishes fiction, not the resolution. It’s the powerlessness in the self that makes its way into fiction.”

“I became fascinated with the distance between the man who presented himself to the world – scholarly, buttoned-up, distant, serious – and the figure in the diaries who was not like that. There’s the secret erotic life in the diaries, and in the novels, but he himself was a father of six and behaved accordingly. It wasn’t as though he set about embarrassing his family. He didn’t go out into Munich at night, cruising the parks – at least, we’re pretty sure he didn’t. I thought these things were dramatic and worthy of representation.”

There's a quote about your collection of essays Love In A Dark Time where you say you had pure admiration for figures, unlike yourself, who weren't afraid, where you’re talking about Wilde, Bacon, and Almodóvar. Was Mann’s secret life something that spoke to you as a young gay man?

“There are elements for someone like me who was bought up, in certain ways, in the nineteenth century. So many things were open to debate in Ireland in the early seventies. I was in St. Peter's boarding school in Wexford, but everything could be debated. The priests spent summers in America, so there was a lot of openness, but homosexuality was never mentioned. It wasn't as though it was forbidden to be mentioned, it wasn't mentioned enough to be mentioned. And you lived in that state of strange invisibility. That changed when I went to UCD."

“There are scenes where Mann attempts to explore a teenage sexuality, when he’s staying in a boarding house in Lübeck and when he's walking the streets of Munich, he's unclear himself what he’s actually looking for. I think the reader might know, but he doesn't. These were things that were almost unresolved for me and it wasn't as a literary exercise. I wanted to explore not just the idea of an uneasy sexuality, but an unmentioned and unmentionable sexuality.”

The Story Of The Night

Was being a gay man in seventies Dublin difficult?

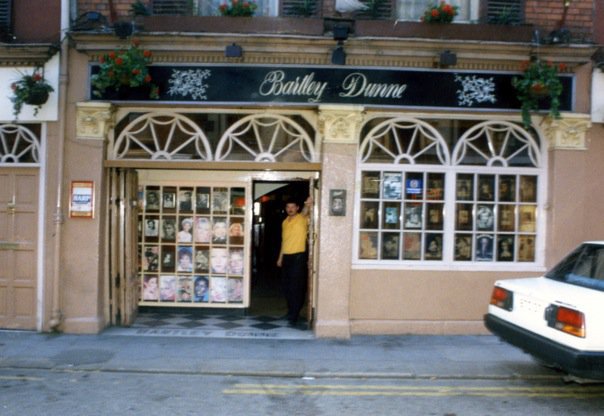

“I have a book of poetry coming out [Vinegar Hill] and there’s a long poem in it about two men. They decide to go into Dublin Castle on the day of the Same Sex Marriage Referendum, but they’re in their sixties and they don’t know anyone. They go for a walk by the places, the shadow places, the dead places where gay men went in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, because that’s their world. It’s sort of a map of an old gay Dublin."

“They go up to Bartley Dunne’s, which is not there anymore, of course, but was fashionable, and then Rice’s, which was at the entrance to the Stephen’s Green Centre. The front room was gay, the backroom was not, but they were the two pubs. As time moved on, Dublin really was one big sauna, and straight people didn’t see. There were, I think, four or five gay saunas in Dublin, and the public toilets, the toilet on Burgh Quay, were all cruising grounds – so if you were a gay man, you had your own map of the city. We all had secret lives, and the city was a secret place.”

Change happened slowly…

“People were working on changing the law, but it didn’t look likely. The Supreme Court judgment in the Norris case, delivered in 1983, was by any standards an absolute disgrace. The Chief Justice decided to take evidence that had not been presented to him in the court, and had not been tested in any way – some of it was hearsay – and put it into his judgment as fact. So ‘83 looked awful, but it didn’t matter in a way because the cops had more or less given up, there was no one being arrested. They didn’t bother with the law, and they let people know."

“People were out to their friends not their family; out to some of their friends, out to their family, but not their granny; out to their friends and their family, but not out at work. So many people had compartmentalised various elements of themselves, their relationships and their sexual identity. That was part of the deal in Ireland.”

Is there anything about the clandestine nature of it then that you miss?

“People certainly talked about that. I think I have a joke in the poem that orgasms were longer before decriminalisation. You were sneaking through a city to an assignation you’re not sure of, it was happening, both in plain sight and also fully invisible. People do talk about that. I think it’s nonsense, actually."

“I think the big change is that if you’re fourteen now, and you think you’re gay, there’s information. You don’t go through the idea, ‘Is it just me? How will I ever live?’ I think that part has certainly been improved upon, so I don’t think people should complain. It used to be a wonderful complaint, ‘God, I haven’t had any decent sex at all since that bloody decriminalisation!’”

Was there a frisson of excitement because it was a “criminal act”?

“The excitement was not knowing how it would end. In other words, going into a place with no group of friends, you’re not socialised, therefore you’re fully sexualised in that space. The outcome could be amazing because you could meet someone entirely new. You’re talking about a world in which no one seemed to be looking for a relationship. We’re not settling down in the suburbs, and the bank wouldn’t give you the loan with your gay partner."

“It’s not danger you’re interested in as much as the excitement. It could be him over there. Look who’s just come up the stairs! That was exciting. In the straight world that would have been about groups of friends, about the need we have to socialise a relationship before you sexualise it. With the gay thing, you didn’t have to bother!”

Is it a ridiculous notion to think some straight men might be jealous of that?

“Ah yeah, you used to hear all that. 'You guys have all the fun!' You just sort of run things, you know? When was the last time you saw an ad for a car with someone gay?”

Death And Venice

Thomas Mann doesn’t come out of The Magician very well. His son Klaus dies by suicide and Mann stays on a book tour rather than attend the funeral. He's not a decent fellow.

“Part of the interest was a protagonist in a novel not heroic to himself or his family. This man is not kind, he’s not good, yet we watch him doing his best in some circumstances, and not in others. I was interested in that sort of moral cloud. People expect people in novels to be good, but if people in fiction are only good, surely we’re missing half of life?”

In America, the newspaperman Meyer tells Thomas Mann to stop publicly calling for America to enter World War II – and that, if he keeps quiet, he might end up as the next German head of state. Did that really happen?

“It was talked about in Washington, that in a defeated Germany, somebody would need to bring it all together, who would be above everything and would have not been involved in any of the war effort from the German side. Thomas Mann was certainly mentioned in this way.”

Like a historian, Colm adopts the present tense to elaborate.

“Roosevelt trusts him but he doesn’t want some very powerful German figure ranting about American entering the war. He’s having enough trouble with Congress and his own party. He also doesn’t want Mann as an opponent on the whole issue of refugees, because America has really closed its doors. What they want to do is sort of edge into the war. Of course, Pearl Harbour is a gift, because they’re actually forced into it.”

Did Mann redeem himself by recording the anti-Nazi messages that were broadcast by the BBC?

“I don’t think redemption is on the cards. People who hadn’t been in Germany during the war, really have no place in the new Germany, so Klaus had nowhere to go after 1945. It’s not as though the suicide was caused directly by his father, but Thomas Mann was obsessed with his own work and routines, and having these really unruly children didn’t interest him very much. There are fathers like that everywhere, and their sons don’t commit suicide. You have to be careful not to blame him for things that he didn’t really cause directly. But you’re right when you say he didn’t want to go to the funeral. He didn’t want to fly down and walk through this French town behind the coffin of his son.”

Did you visit the locations in the novel?

“I was in the house his mother was born in, in Brazil, and the houses in California, Princeton, and Munich.”

And take notes?

“No notes. If you can’t remember, it’s not worth it. And you lose notes or forget what they mean. Go in with no pen, no pad, no paper, and just watch and soak it all in. Notes would be unhelpful.”

When you're writing about real people, can you take liberties?

“In a novel like this, your responsibility is to create an illusion so your reader isn’t asking all the time if this is true or not. My responsibility is to create an illusion. There are obviously passages of dialogue that I could not have known, but if I say he was in Munich that year, he must have been. I can’t make that up. But all the stuff in the middle, I have to imagine.”

It is a novel, after all.

“You can say it's a novel, and therefore, there are no rules and It's imagination, but if you're calling him Thomas Mann, and you're saying he was born in this year, then you can do any postmodern tricks you want with that but, in my view, you have a duty to follow the facts, to a large extent. As for the matter of his sexuality, as to how much of that you can put in and how much you can leave out? He put it into his diaries. I didn't make it up. He wrote Death In Venice. I didn't write it. But nonetheless, when I went with the book to Germany, they were uneasy about that.”

The diaries don't leave us in much doubt. He admits he was in love with his own son.

“In the diaries he finds the fifteen or sixteen year old Klaus naked in a room and he thought this was incredibly beautiful. He felt sexual desire for him. Yes, he wrote that down. That happened.”

Death In Venice is problematic. The story of Gustav’s obsession with this young boy Tadzio could hardly be published today.

"I don't know if you've seen the documentary called The Most Beautiful Boy In The World? [about Björn Andrésen, who played Tadzio in Luchino Visconti’s 1971 movie version]"

I have.

"I think it’s clear from that documentary that it wasn't just problematic when Mann wrote the story in 1911/1912, it was problematic when Visconti made the film. The footage of the boy in the audition, with Visconti getting him to take off his shirt, whatever is going on there is wrong. Mann attempted to make the boy in the story symbolic, in some way representing beauty, but when we read it now we know very well what it is, it's an older man looking at a teenager with lust. I don't think you could write or publish it now when we're much more alert to what those images result in, which is basically abuse and ruining people's lives. Even publishing that book has a way of making these things sort of almost normal, almost acceptable. The book and the movie belong to a time before now."

Gustav spruces himself up and contemplates the Platonic ideal.

"He’s working his way around areas of his own desire and trying to find metaphors and context for them, and he's doing it with the Greek ideal. He's also bringing in notions of decay, with cholera coming to Venice, a Europe of sickly beauty, so he's working in a lot of ideas. It's not a simple thing, in the same way as Lolita is so playful with its language. It's not as though these are simple pieces of pornography, they're emphatically not that."

If it were to be published now, Mann would be cancelled.

“Just now, a book like that, would, I think, not be written and published.”

What’s your opinion on cancel culture?

“I think a lot of people feel that the law has broken down. I think that’s particularly the case with rape. There’s always been an interest in people taking the law into their own hands. With cancel culture, you can get people at night on their own in rooms, stirred up by images and words, and you get this extraordinary outpouring of rage."

“I don’t have the stomach for it,” he continues. “I don’t believe in it. I believe that the systems of justice that have been evolving for two-thousand years or more, the idea of trial by jury, are imperfect – and perhaps should be improved – but if we give up on them to think there’s another way of declaring people guilty, then I think we can only lose in that.”

Is it a climate that might make artists second guess themselves?

“I don’t have a problem with woke. I teach in university, and there are a lot of young people from different races. There’s the question of gender and the question of people who are transitioning, and it seems to me that woke is being mannerly. The main thing to do is to try not to hurt people’s feelings and that might seem a small thing but sometimes you have to make an effort not to hurt someone’s feelings, whether in a remark or an attitude, or in some prejudice you may have. I think there’s a distance between the cancel thing, which actually happened very little, and the woke thing, which is a big phenomenon and it seems to me to be, in general, a good thing.”

It doesn’t take much effort to respect people’s pronoun choices.

“Yes, and a lot of people who are sixteen and seventeen have a duty, I think, not to listen to adults too much. You should actually respect people of that age and find out what it is they want, what it is they’re thinking about. There are many new things happening, new rules surrounding what you can or can’t say, I’m not sure all of them are equal, but I think the woke thing has a lot to be said for it.”

Tóibín with a fan at The Irish premiere screening of Brooklyn at The Savoy Cinema Dublin,

Tóibín with a fan at The Irish premiere screening of Brooklyn at The Savoy Cinema Dublin,Pic Brian McEvoy

Endgame

In the middle of writing The Magician, cancer, as you so succinctly put it, “started in my balls.”

“I had written four chapters. It wasn’t that I was postponing thinking about the cancer killing me, the worry was that the chemo was really heavy. But it works, because it kills the tumour. The first round took more or less six months and if you had to do a second round, it would put writing off the agenda for a very, very long time. I was worried about it."

That's what you were worried about?

"I’d four chapters – and the book would never get written.”

But surely that’s the last thing to worry about?

“No, no, no. It’s an unfinished thing. You’ve imagined it all. You’ve started the book. It’s been on your mind all the time. It was one of the things I was really worried about. I wouldn’t be alone in that. I think other writers would nod and say, ‘Oh my God! Halfway through a book!’ The crisis of mortality, of your immortal soul and all these things matter – but I was just stuck with my book, my book, my book! You can think about twenty things at the same time, so I was thinking about loved ones. Of course, I was. But actually, what I was really thinking about... It’s not on. It’s shameful what I’m telling you. It’s shameful! I should be ashamed!”

You've mentioned the book of poetry. There's also Brooklyn, Part II?

“I was never going to do it. I promised I wouldn’t – I hate sequels – and then I got an idea. Walking down the street something occurred to me, and the minute it did, I was off. It’s not a sequel to the plot; it’s the same characters and something new happens. And that causes a lot of drama.”

Which you’re now going to tell me all about?

“No.”

People who’ve had brush with mortality sometimes talk of a sense of renewal. Have you learned anything?

“No, no, no. That’s all rubbish. I’ve learned nothing.”

__________

The Magician is published by Penguin/Viking