- Culture

- 14 Aug 19

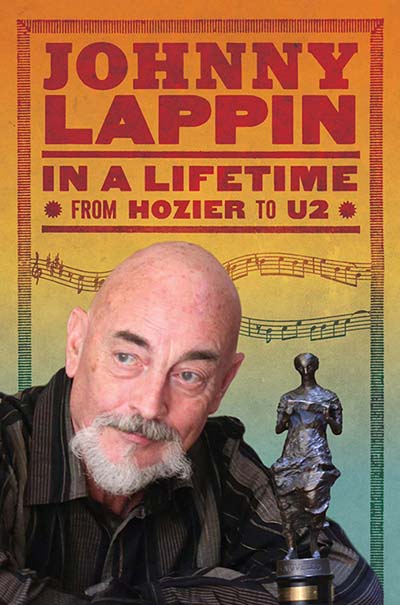

Interview: Johnny Lappin on Hozier, Clannad, U2, and Picture This

One of Ireland's pioneering music publishers, Johnny Lappin looks back on "a good life" and some good characters in his memoir In A Lifetime: From Hozier To U2.

A career in painting and decorating – “it bored the shite out of me” - isn’t for everyone and the music bug had bitten into young Johnny Lappin good and early. “Blame The Beatles, I was twelve when ‘Love Me Do’ came out. I started off trying to be a singer. We were supporting The Dubliners and Luke Kelly. That’s when I realised I couldn't sing. I tried to be a drummer too but I had a bit of a problem in that I couldn't keep time.”

Setting sticks aside, the next rock n’ roll hat our hero tried on was management. “I’d go see Stepaside in The Merrion Inn around 1975, I loved their good time rock n’ roll sound. I was looking for a way to put my business knowledge to use in music. I started off managing them. That's how I got in, but I found managing people a difficult thing to do.”

It’s at this point that the narrative in Lappin’s book really gets going. In fact, it’s in the back of a car on the way to the Macroom Festival in 1978, when a mate bemoans a lack of knowledge about music publishing. A light bulb materialised above Lappin’s head. The idea of “managing songs” had more appeal to him than managing people. To quote the book, “Songs wouldn’t argue with me, or turn up late for meetings, or piss me off.” “That’s how I started the search,” Lappin remembers today, “to find out what a music publisher did.”

A good question that. “Essentially their job is to maximise the earnings from songs, for themselves and the songwriter,” Lappin smiles at an inquiry he must have heard countless times before. “Everywhere that has music - hairdressers, shops, bars, whatever - has to have a licence for public performance. That money is sent to IMRO and then paid out to the publisher and the writer. The job is to exploit the song in any way possible, to earn as much money as you can.”

Hustle’s the name of the game, as Glen Campbell once sang, and Lappin was an enthusiastic player, setting up Scoff Records, one of Ireland’s first real rock labels, with Deke O’Brien (Stepaside’s singer) and its sister publishing arm, Dark Fox Music, and schmoozing with DJs from the nascent RTE Radio 2 – “they all drank in Madigan’s in Donnybrook, we’d refer to it as RTE3”. Lappin even won the coveted Hot Press Ligger Of The Year in 1977, but slightly more substantial and financially rewarding success was just ahead.

Old pal, the late Dave Kavanagh, took over managing Clannad in 1980, and played Johnny the ‘Harry’s Game’ single. “I said to Dave, and I think it's in the book, ‘That'll either be huge or it'll die a death’ and, as we know, it was two minutes and thirty seconds of music that changed our lives.” Lappin gave Kavanagh the three magic words to use when dealing with RCA, “retain the copyright”, after which Kavanagh invited him to form Clannad Music Ltd.

“He was always a bit of a visionary,” says Lappin, remembering his friend. “He saw Clannad’s potential as an international band and he was right because within two years they were number one.” Lappin worked, very successfully, with Clannad and Kavanagh until 1990. “Dave did the deals, threw the paper over his shoulder, I’d grab it, smooth it out, and put it in the filing cabinet. That's why the relationship worked, but the operation got too expensive. I said to him ‘the biggest expenses are you and me, one of us has to go, and I guess it isn't going to be you!’”

Many more adventures in the business of show were to follow. As well as working again with Kavanagh and the Celtic Woman ensemble, “when it crossed over on PBS in America, that’s when we knew we were onto something”, Lappin was a crucial cog in the establishment of IMRO, offering Irish songwriters and musicians greater protection than they’d enjoyed under the London based Performing Rights Society. “The PRS had a guy in an office and two reps covering the whole country.” He butted heads with RTE over their handling of the Eurovision Song Contest. “They went from a live orchestra to backing tracks, and that fundamentally changed everything, along with the move from expert opinion to public vote. It’s not a ‘song’ contest anymore.” The man has little time for tv talent shows either. “I don’t like them at all. It’s cheap television, taking advantage of young kids, and it affects the losers in a big way.” He’s currently contesting the pittance artists receive from the streaming giants. “That's occupying a lot of my time. We’re trying to get those rates up. Think about it this way, who are the major shareholders in Spotify? The big record labels.”

On the subject of songs, what is it that Johnny is listening for when someone approaches him? "What I as a publisher am listening for is different to what a record company are after. I need to know if the writer is writing for themselves, to be a singer-songwriter, or if they're writing with a view to being a writer for somebody else. If that's the case I ask who they think the songs are suitable for? I need to get a feel for where their head is. I'm listening for the commercial viability of the song. Has it got a great hook? Will it get played on the radio?"

That being said, he freely admits he can miss the mark too. "The first time I heard Extreme's 'More Than Words', I hated it. There's a lot of strange chords in there but it went on to be a huge hit. I would have thrown that demo out. Music is subjective, everybody hears it in different ways. Remember, the guy from Decca told The Beatles there was no future in guitar bands!"

Once introduced as “the man who was in the right place at the right time, twice.”, Lappin’s second big score was the rise of Hozier. He was working with Denis Desmond and Caroline Downey’s Evolving Music who had secured Hozier’s publishing early. After Stephen Fry retweeted the video of ‘Take Me To Church’ to his 19 million odd followers, Lappin faced a deluge of requests. “I instinctively knew this was huge and the cat and mouse game of negotiations began in London in November 2013” The chapter that details these haggles is fascinating.

“When everybody’s chasing you, that's when experience comes in. They're trying to use their leverage - we are Sony, or whoever - but I knew how important it was, and I was confident, and in fairness to Denis Desmond, he let me negotiate that publishing deal.” The song took home an Ivor Novello award in 2015, Lappin still beaming at the memory. “One of the best moments of my career at the Oscars of the music industry!”

A career that seems far from over, Lappin having recently worked with pop juggernaut Picture This. "Their manager Brian Whitehead rang and sent me their first couple of songs, which I thought were really, really good" he explains. "They took me on as a consultant and I advised them on their deal, although they had a lawyer doing the negotiating. I advised on the lawyer's comments, which was fun." That's not the end of it either, Lappin still has the eye and ear out. "I'm just about to sign a couple of Wexford Acts. Wolff is a very smart guy I met at Music Cork. He came up and showed me his stuff on YouTube and I liked the cut of his jib. I'm also looking at a young band from Enniscorthy called Ten Ounce Mouse. I gave them advise and they listened."

The Irish music industry may have changed beyond all recognition since that trip to Macroom, but good advice is still worth its weight in whatever's going. "I got an email recently with a link to thirty demos and two words - 'any advice?'" he laughs. "When I started in the business, I went into Eason's and bought every provincial newspaper I could find and I spent a few weeks compiling what would now loosely be know as 'The Hot Press Yearbook', but the industry has changed. Kids today don't understand that back in the day there was no internet, it was all trial and error. There's so much information out there now, there's really no excuse not to know how this business works. I've always tried to give as much as I can back because I've had a great life. I've never made any fortunes but I've had a good life."

There was one big fish that did kinda sorta get away though. “I was walking round by Trinity, this young fella stopped me and asked ‘Are you Johnny Lappin? The manager of Time Machine? You're playing the Baggot Inn?’ I said ‘Yeah, what is it?’ He said his name was Bono and his band U2 wanted the support gig. ‘Just send the tape into my office’ I said dismissively, but they never did. I saw them in the Dandelion Market and I knew Paul McGuinness. The likes of McGuinness, Dave Kavanagh, Pat Egan, and myself were the pioneers of the Irish rock n' roll business, and I'm very proud of that. I feel privileged to have been there at the start, and privileged to still be here now.”

RELATED

- Culture

- 27 May 25

Bono: Stories Of Surrender - Father, Son, And Holy Ghost

- Film And TV

- 01 May 25