- Opinion

- 14 Feb 23

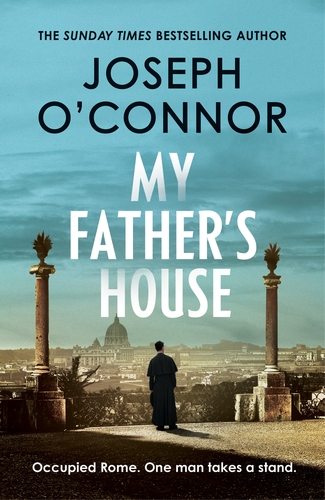

Interview: Joseph O'Connor on My Father's House - "It's a great story because Hugh O’Flaherty was a person of extraordinary physical courage"

Joseph O’Connor’s new novel tells the thrilling tale of an Irish Priest’s resistance during the Nazi occupation of Rome. “It’s a great story of extraordinary courage,” he tells Pat Carty.

In his long and varied career, Joseph O’Connor has written plays, lyrics, non-fiction and short stories but the novels are the reason why his mantlepiece is overcrowded. Star Of The Sea, his marvellous 2002 famine story, has sold over a million copies and been translated into forty languages, and his more recent Shadowplay, which reimagined Bram Stoker’s London, took the Novel Of The Year gong at the Irish Book Awards. The readers of this magazine once saw fit to vote him Irish Novelist Of The Decade.

His latest triumph is My Father’s House, a brilliant recounting of Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty’s adventures in the Vatican during World War II where the Kerry-born cleric provided, with the help of his choir of associates, an escape line for prisoners and the persecuted from Nazi clutches. It’s the kind of hold-all-my-calls story that armchairs were invented for.

“I went through the usual process, which is to try and get the music of it in my head,” O’Connor explained during a visit to the HP office. “I have the start, I have the characters, I usually have the end, and then I try and get what it's going to sound like. Not just the characters or the situations but the effect the sound of the words are going to have. I think Star Of The Sea has a sound and Shadowplay has a sound.”

O’Flaherty’s friends, the “choir” that he assembles to aid in his endeavours, some of whom will feature again in two further novels that are promised from O’Connor, are English, Irish and Italian, which gives the author further resources to work with.

“The challenge is to make the eight characters sound different, but the opportunity is to celebrate the fact that we all speak in a different way. Listening to people speak is musical. If you're walking through the streets of any great city, it becomes part of your soundtrack. It certainly does in Italy where people talk with such physical flare. It's also about atmosphere. I suppose I was thinking of Noir, those classic black and white movies. There’s also the religious music and you can't write about Italy without having some reference to the opera. I thought about it in terms of organising a set of sounds as much as organising a story.”

Coming across a tale as thrilling as O’Flaherty’s would be cause for celebration for any writer. O’Connor first heard tell of him in Kerry.

“I’ve been going to Listowel Writers’ Week since before I was published,” he recalls, with obvious affection. “And late one night in the bar of the Listowel Arms somebody told me the story of as Hugh O’Flaherty from Kerry who had been a priest in the Vatican and the risks that he took to save all of these people.”

The Monsignor joined O’Connor’s list of potential subjects.

“I'm always carrying around a set of characters in my head that I might write a novel about. I don't sit there and wait for the muse. I'd love to write a novel about Joe Strummer, or Grace Gifford, or Micheál Mac Liammóir or Parnell. My last novel Shadowplay came out, I started thinking about the next one, and Hugh started knocking on the door a bit. I wrote a few thousand words, it seemed to be going well. We went to Italy, fell in love with Rome, and it just wanted to come out.”

The character of O’Flaherty seems purpose built for novelisation. An admirably learned man of faith who risked his life to do the right thing.

“I always thought it would make a great story because he was a person of extraordinary physical courage,” O’Connor agrees. “I was thinking of a Marlon Brando doesn't take any shit kind of tough guy. I've read all of his papers, his family gave me his letters. He loved sport, boxing in particular, and his turn a phrase is, here and there, quite macho. My conception of him is that he was that kind of strong and silent type.”

“What made him interesting to me is that he spoke seven languages but in the letters back to Kerry, he's interested in gossip and music and what's going on in the small town. I thought that could feed into how he talks to people in the book. I didn't really want him to be, as one of the characters says, an Irish priest in a film as played by Bing Crosby. I wanted him to be more Russell Crowe!”

There is a rather good tv movie called The Scarlet And The Black starring Gregory Peck with a wavering accent. O’ Connor has seen bits of it but refers me instead to a TG4 documentary made by O’Flaherty’s grandniece Catherine called Pimpernel Sa Vatican.

“She unearthed really great stuff including an audio recording of a This Is Your Life programme, a fictional version of which concludes the book.”

The Monstrous Evil

The villain of the piece is Obersturmbannführer Paul Hauptmann who I would have thought was based directly on the real-life Nazi monster Herbert Kappler, the man responsible for the Ardeatine massacre amongst other crimes but O’Connor is keen to distance his creation from such a supposition.

“He isn’t,” O’Connor insists. “My character strays so far from the real person that I thought he better have another name. I also didn't want his name in the book, I didn’t want to equate O’Flaherty and him in any way, even accidentally. I didn't want to be thinking about him as I was writing. I created a fictional character but it's morally ambiguous stuff when you're talking about real people, you have to make sure that you're not using other people's sufferings to provide the page-turningness of a thriller.”

Was the addition of Hauptmann’s family an attempt to humanise him?

“It's very uncomfortable for us that the Nazis were human. The first impulse is they're monsters because it's hard to process that they're not. That’s the real obscenity of the Second World War, and the obscenity of what continues to happen when there's violent racial discrimination. We’re doing this to each other. It was an attempt to portray him as a man and the unfortunate thing about him is that he is a man, married with kids he cares about, who kills people as part of his job. He's persuaded himself that it's morally necessary.”

“The monstrous evil and vicious racism for which that decade is so infamous was all perpetrated by human beings. It's a terrible thought but at the same time, the book proposes that we also put ourselves into extraordinary danger to help people we didn't even know. The human race has done this evil but there’s also the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. There’s also Aretha Franklin. There’s also Bach. It's not all bad.”

The Papal Edict

One of the novel’s memorable scenes finds the Pope himself berating O’Flaherty for going against Vatican policy. To be fair to the real Pope Pius XII – not a sentence I ever expected to type - he had, as Pius XI’s Secretary Of State, protested against Nazi actions and helped draft the Mit brennender Sorge encyclical which challenged Nazi ideology in no uncertain terms. For his 2012 book, The Pope’s Jews: The Vatican’s Secret Plan To Save Jews From The Nazis, British author Gordon Thomas spoke with O’Flaherty’s family who informed him that O’Flaherty claimed everything he did was done with the Pope’s co-operation.

“I think there's probably an ambivalence about it,” says O’Connor. “It probably changed from day to day, and if there's one thing that senior Catholic Church figures are very good at, it's thinking two things at the same time. I think that he absolutely felt that the public message should be ‘I didn't condone this’ but he might have said something totally different.”

Would the policy of neutrality have been adopted to physically protect the Vatican’s treasures?

“That’s a big part of it. In the history books you see that the Vatican are really concerned that there may be tanks rolling into St. Peter's Square, and the Vatican museum may be burned to the ground. The physical, cultural, artistic heritage of the place is at risk. The Nazis are at the end of the street. If you've been to Rome there is the painted line on the ground, the boundary past which you had the whole Nazi army. They're looking for a reason to break the Lateran Treaty [which recognised the Vatican as an independent state] which only existed since 1929 and the Pope is trying to keep that from happening.”

“Hugh is a Catholic priest who's taken vows of obedience. The Pope has personally told him not to do this but he decides ‘I'm going to do it’ and that's a story. I love and respect the Pope but I have to do this. I don't have any choice. I can't live with myself. He's a really intriguing character because he has to do what he thinks is right.”

The current Pope cried during a public prayer as he spoke of the suffering in Ukraine, which is all well and good, but could the church be doing more and could they have done more during this period?

“Of course, but you and I can meet another day and talk about the things we think the church could have done. My job is to create a story where all the characters are credible, so nobody has to be a complete hero or a complete villain. The Pope tearing shreds off O’Flaherty has to be real enough to read. Rather than the Pope being a bollocks or very shallow, I made him kind of stylish. He's talking about Shakespeare and he's ironic and sarcastic. ‘I’ll genuflect before you, O’Flaherty.’ I think that's my job rather than to take sides.”

“I'm not a practicing catholic and I’m not here to propagandise on behalf of the Popes. What I would like to talk about is the book. We went to a mass said by the Pope in the Vatican on Christmas Eve and the theatre of it was splendid. It's probably the first time I've been to a mass that wasn't a funeral since I was seventeen. The Catholic Church is not part of my life. At the same time, if you're writing about a priest where it's not Father Ted, you have to reconcile yourself to the fact that he's strongly motivated by and believes in the central tenets of his faith. I'm not going to take the piss, I'm going to portray him with the respect that I feel for the real Hugh O'Flaherty and take my views out of it.”

Was Ireland’s policy of neutrality the right stance to take during this period?

“In short, because I know we don't have a whole lot of time to discuss this, I do. I understand why Ireland was neutral when the country had decades of extraordinary violence, and won a bloodily contested version of its freedom. We finally, out of this horrible, bloody mess, create a country that has courts, and a parliament, and is beginning to put together all of the things that a country needs, with the terrible inequities and all of the caveats that we would have about the past. But it's only been doing this for twenty years, and now we're going to get involved in a world war? As the father of young men, my vote would have been no. I would not have wanted my sons to be sent into war. To have the choice of doing it is another thing, but I wouldn't have wanted what happened to so many people around the world to have happened here, and I understand why it didn't.”

Is it not morally wrong to be neutral in the face of such evil?

“The reason why you and I are talking about it is that it's morally ambiguous. It’s not like being in favour of ‘She Loves You’ by The Beatles. Who isn’t? It’s a moral and ethical and political minefield. It should always be debated with great care. I would add that, as you know, thousands of Irish people did fight in World War II, a number of my own relatives among them. Irish people have fought very courageously on the side of right or on the side of peacekeeping, as they still do. I think it's one thing to have the choice to do that, but it's another thing to have the government telling you to.”

What about neutrality now, in the time of Putin’s aggression?

“Well, I don't think we're neutral. I mean, we’re politically neutral, but there's no doubt at all of the Irish government's stance and the Irish people's stance in general. We're not neutral when it comes to Ukraine.”

Faith & Doubt

Returning to the character of O’Flaherty, I asked O’Connor about the kind of faith that drove him, something that I find admirable despite not possessing it myself.

“I had a religious phase when I was in my middle teens and then I was an atheist for decades. Now, I’m a doubting believer or a believing doubter. I have a religious impulse, but I am not part of any church. It must be great to be completely clear in your mind one way or the other. I envied people who were completely happily atheist too. I feel okay about having doubt. I think it's human to doubt.”

What do you mean by doubt?

“There are days when I am sure and then I hear Aretha Franklin singing ‘Amazing Grace’ and I'm not sure at all. When I hear gospel music or Bach or Palestrina, I do believe and I can't make the leap that atheism would be.”

The inexplicable magic of music?

“It is inexplicable and it is, to use an overused word, spiritual. There really isn't a way to explain how if you play the blues, there will be a set of feelings and, if you speed it up, it becomes rock and roll with a completely different set of feelings. I don't even understand why a minor chord is sadder than a major chord. Cole Porter’s lyric, “how strange the change from major to minor” is just so beautiful. I think Yeats would have chewed his fucking leg off to have written that. Nobody's able to explain the way Aaron Neville makes you feel. Nobody can explain how when you listen to Séamus Begley, no matter what part of Ireland you're from, there is something of you going on in that music.”

“Something is being expressed that writing doesn't do, that painting doesn't do. They do beautiful things, but nothing else really does that, which, for me, is proof there is mystery in our daily experience. Music is probably the most universally loved art form yet it’s so abstract. When you think about it, music doesn't sound like anything but itself and yet we have this need and reverence for it. What more proof do you need that there is stuff about life we don't yet understand? When I hear music, I believe and I know that there's something going on in life that has not yet been quantified.”

“Maybe it will be one day, after every civilisation has called it ‘God’ for thousands of years, because we haven't got another word yet. There is a world we can't see and anyone who thinks there isn't, I admire their certitude, but I can’t make that leap. If you had told me in school that one day they'd be able to tell a drop of your blood as different from my blood, ‘there’s this funny DNA thing that's unique to every human being’ people would have laughed. That's only just been discovered, there's a lot about our existence that we do not understand.”

“There is something of spirit in music, it's the most powerful of the art forms, and it comes from some world that we don't even yet have the vocabulary to fully talk about. You're a music critic, a music fan, I'm a music fan, I listen to music every day, but I'm not able to explain it.”

It’s the universal language. I can hear something from Mali and be deeply moved. I don't need to know what they're singing about. To read your book I must first learn how to read, but I don’t need to be taught how to listen.

“It seems, as far as we know, to be innate. Most children sing before they can talk and as they begin to speak, one of the ways that they do is through music, because our earliest experience of language is the nursery rhyme, the language of the lullaby. That's why I'm saying prose for me has to have music, because if it does, you're going right back to the reader’s first experiences of language. Look at Joyce, perhaps the greatest novelist of the twentieth century, the man who wrote Ulysses and was capable of the explosive fireworks of Finnegans Wake. Portrait Of The Artist begins, ‘Once upon a time, there was a nice little boy called Steven and he was walking down the road and he met a moo cow.’ Joyce understood that language is actually pre-verbal, it's music before it becomes language. I think that's what we're responding to when we hear singing from Mali or music from other countries.”

“It might be that we are not quite able to say what we mean. That's why we have music. Language can do so many wonderful things but as T.S. Eliot says, in The Love Song Of J. Alfred Prufrock, “That is not what I meant, at all.” We fail every day with language, with our friends, our spouses, our kids. If you get it to eighty percent, that's really good. The work of the novelist is to try and get to one-hundred percent in every sentence, which no one's ever going to do. It’s a beautiful but brittle medium, but it's hard to be precise. The first thing we do is cry, the first thing we do is use our vocal cords.”

The first thing we hear is a heartbeat.

“Yes. You've got rhythm and melody, almost before you are born. That speaks to me of spirituality or the mystery or the ‘Godness’ of life.”

__________

My Father’s House is published by Harvill Secker