- Opinion

- 07 Jan 20

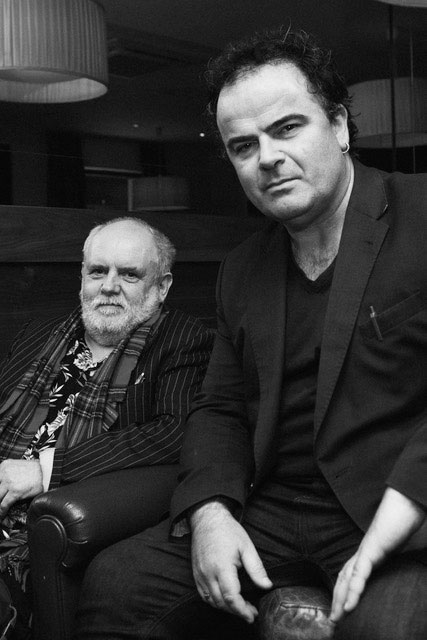

Out Where The Buses Don’t Run: Patrick McCabe resurrects his most infamous character, Francie Brady, for his new novel The Big Yaroo. “There’s an anarcho-hillbilly thing I’ve always felt a kinship with”, he tells Pat Carty.

The success of The Butcher Boy in 1992 – The Irish Times Irish Literature prize, the Booker Shortlist, and, later, Neil Jordan’s celebrated movie adaptation – bestowed an unlikely status on Clones man Patrick McCabe. “It still astounds me, having written a book where a woman is brutally chopped up, to be introduced on the radio as a national treasure, you think is there something wrong with the psychology of this country? I'm not saying that I won't accept it, but it's pretty damn strange.”

McCabe returns to his most famous character, Francie Brady, in his latest novel, The Big Yaroo. The obvious question is why? “In a way Francie is an alter-ego, to be honest.” McCabe admits. “People might have a different relationship with the idea than I do, I don't think in terms of books or careers or anything like that. The voice either fits a period in your life or it doesn't so I would never feel ‘Oh, I'll write a sequel.’ I wanted to do justice to whatever feelings or philosophies I might have at this age and, to write about those things, it had to be authentic."

The reader's first thought - certainly my first thought - when I heard a sequel was in the works was the worry that it just mightn't be as good, I was putting off reading it. McCabe is, of course aware of this.

"I'd say that will be a general reaction because people bonded so much with the first one. 'He's getting old now, he's running out of ideas he's going back to warm over beans', that's what they might think.

Francie is an older man, now about the same age as the author, so is there a bit of looking back and putting things in order?

Advertisement

"Totally and unashamedly," McCabe allows. "It wasn't easy, but that's what it is."

McCabe isn't one to hang around, waiting for inspiration, he sits at a desk and puts the work in.

"I do, yeah, always have. You wouldn't be much or a writer if you only wrote when the muse came. I kind of figured that out early on, that most of the time it wouldn't be much good."

The first draft of anything is shit?

"It stands to reason, you'd want to see the first draft of this! Dreadful."

Through hard graft, McCabe eventually got to the good place.

"There's a certain kind of purity that I was looking for and it didn't come until very, very late. It's like musicians tuning up except you're spending two years tuning up until you get into the key, is it e-major, no that's wrong, is it fucking a-minor? No it's not. There might be a diminished in there that just gives you the conjunction, and you get into the key then, and that's what it was like. That came very late on, and all the stuff about the Q bikes and the magazine, all that stuff came in a rush. It wasn't a question of showing it to agents, I'm not interested in that, it was 'could I stand up and read this to an audience and believe every word of it and convince them of it?' and I could."

Advertisement

Daydream Believer

Francie is a resident of the ‘Fizzbag’ psychiatric Hospital in South Dublin, a literary device that McCabe explains. “The hospital only fulfils the function of the island in Robinson Crusoe or the prison in The Borstal Boy in that it reflects the personality at different times and different social changes, but I would never say The Butcher Boy defines anything about psychosis. People described Francie as a psychopath but he feels very strongly for one. I always understood that psychopaths mimic feeling and didn't really feel anything, so I think you'd need to come up with a different term. Hyperesthesia maybe, where he feels too much, but again that's not my business because the making of someone like that, you have to really say like Flaubert said ‘L'état, C'est moi’ or who ever said it. (It was, apparently, Louis XIV, but Flaubert did say ‘Madame Bovary, c’est moi’ so you get the idea.) He kind of is a version of myself, although obviously I don't go around chopping people up.”

One would certainly hope not. The first book referenced the threat of atomic war and Trump gets a mention in the new novel. These factors, it turns out, are merely grist to Francie’s mill. “He's sixty years of age so he has to take some cognisance of the world around him and that happens to be on the TV. He's a kind of a magpie so, anything that's going on, he turns the world into a kind of a cartoon or a comic book with the colour turned up. What he really feels deeply about is love, and for it to have been taken away from him, it was short circuited at a very young age.”

Everything that goes wrong for Francie can be traced back to this event, his mother’s suicide in the first book. In The Big Yaroo, one the fantasy sequences has Googleboy going back to change the past, and Francie’s proposed cycle back home could be read as a longing to go back to this idealised state. “It's a very profound thing I'm attempting there,” McCabe explains. “The relationship between mother and son. For all the talk about sexual politics and everything, there's nothing I've ever encountered that’s as powerful as the female in those small towns and the mother more than anything. So, in so far as if there's a core theme, it's that his heart is broken that his mother is not there. Regret is a very powerful emotion, there's very few people that haven't got something, and I don't mean big transgressions but little hurts that you've inflicted or little wounds that you've incurred yourself. It would be nice to go back and solve them.”

This longing for a halcyon past is signposted by Sandy Denny’s marvellous ‘Who Knows Where The Time Goes’ in the text. When I mention this, McCabe produces a picture of the front cover of the Unhalfbricking, the 1969 Fairport Convention album that first featured the song. "I brought this just in case we might mention that, do you know who they are?" he asks, pointing at the distinctly middle-aged couple in the foreground. "They're Sandy Denny's parents. I was looking at that while I was writing the book, with all the freaks in there, the band, at the back. I was around the same age as her then, a bit younger, I didn't know they were her parents. The kind of regret they'd have. Sandy went off, and then died at 31, and those parents were totally fucking perplexed about the world she went into."

Like Nick Drake's mother?

Advertisement

"Molly, yeah. That's very much in there, that kind of regret."

The song could be the novel’s theme tune, a wistfulness for a past that was never really there.

“That's interesting that you say that because I wasn’t going to mention it but that's exactly right. That's curious now. It's a masterpiece and she wrote it when she was nineteen.”

McCabe returns to this song when I ask him about the Joycean stream of consciousness technique that he employs with his main character. “That's more from movies than literature, it's all very influenced by David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, and Night Of The Hunter, that was a movie I was very fond of. Stream of consciousness moves like a river rather than building with blocks, kind of like a song. There is always a key song and I don’t know quite why that is, with this one it was 'Daydream Believer' by The Monkees, and Sandy Denny.”

The Monkees might seem at odds with the narrative, but there’s a point to it. “There is a bubble gum aspect to all this,” is his explanation. “Try to think of it in terms of colours, Francie keeps blowing out this bubble.”

The subject of music is still one that gets McCabe excited. “I think where Irish folk music is now is fantastic, Lankum, Lisa O'Neill, Ye Vagabonds, even Fontaines D.C. I think all these people are at the centre of a movement that has almost kind of shot folk music into the stratosphere, it's like they've gone to the future and come back with something. The hard driving vigour of Lankum, it really speaks to me, it's a raw energy I've always liked.”

There’s a reverence for the past but a healthy disregard for it too. “I've no problem with that,” he continues. “I don’t wrap the past in cotton wool. All the literature that I like has some element of lived experience in it, it has the texture of lived, real thing. It isn’t mediated by a screen or it isn’t mediated by the insincere.”

Advertisement

Mucker

Small town Ireland has always occupied a central place in McCabe’s work, almost to the extent that it’s another character, like Joyce’s Dublin or the London of Charles Dickens. “I always felt that small town was my landscape and there was so much there that I had to deal with, I couldn't afford to be going anywhere else. And now that they're fading, now that they're gone, future generations will be re-evaluating these places. There have been really extraordinary books written about the American small town and what it meant and how it formed people and when I wrote The Butcher Boy, people said ‘this horrible place’ but where does it say horrible? Creatively, whether it's a kinship with William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County or Kavanagh's Mucker or whatever, you're born in a place and it's not a question of liking it or not liking it, that doesn't come into it.”

In a way, Francie is a representation of the culchie giving the fingers to the would-be city sophisticate. “There's kind of an anarcho-hillbilly thing that I've always felt a kinship with. People always associate the go-ahead or the progressive with the urban or the metropolitan but, as this is Hot Press, where did rock n' roll start? It started in the deep south of America with Elvis and African-Americans. These people weren't sophisticated country club types, these were wild bucks.”

Francie gets into a scrap with the gougers on Gardiner street, another representation of the urban/rural divide?

"I don't think that really exists anymore," McCabe counters. "It's a good point and I'm glad you brought it up, I don't like forcing that on people but if they come up with it then it must be in there, it's a suggestion that's neatly kind of buried."

Is the character then a representation of an old Ireland that the modern nation is trying to shove under the stairs?

"Oh yeah, I accept that, but whatever ambitions I might have are bigger than that in a way."

Advertisement

What am I missing so?

"You're not missing anything. In The Butcher Boy, he goes back to Bundoran, he's been told all his life that this is a special place and it turns out that even the moment of his conception was a betrayal. Now you're into classical allusions and everything else, the garden of eden. From the day we are born, why are we so ill at ease, what is this unhappiness, this gnawing feeling."

We're tarnished with sin?

"Maybe so, I was brought up a catholic and very much aware of original sin. In times when you're troubled, these are the things that come crowding around you. When he's in trouble, like in Gardiner street, he gets angry, he lashes out. All those elements that you've described of Irishness are all in me - and I presume a lot of them are in you. I can only really authentically access stuff that's in my blood and really pulses deep there. All those things - having being brought up with a bible education, and a small country school, I never forgot them and why would you?"

And if those things aren't there anymore, then that's a bad thing?

"It's not really for me to say."

We can still learn notions of right and wrong from the Bible stories, and, perhaps, appreciate them as just that, as stories?

Advertisement

"Put it this way, Camille Paglia - one of the most well-known academic feminists in the world - is an atheist but she comes from an Italian catholic background. She views all the great religions of the world as great poems and their churches as edifices to cultural expression, and what on earth can be wrong with that?"

Not Everybody Knows How I Killed Old Phillip Mathers...

Francie spends a good part of the novel creating a magazine, called The Big Yaroo, but the reader might find themselves asking if the whole narrative is just a creation of Francie’s imagination. Is any of this happening at all?

“That's a very good point,” according to McCabe. “There was one review of The Butcher Boy - I don't really mind that much about reviews because the horse has bolted - and I wrote to the woman concerned, she felt the narrator was so adroit and so kind of feral imaginarily, that he was playing everybody, and none of this really happened.”

The Butcher Boy does start off ‘20 or 30 or 40 years ago’ which might support her theory. “My feeling when I had written The Butcher Boy was that I was going to reveal that, I was going to say it never happened. There was a bit of resistance to it - not much - but it would have confused some people and they'd rather that it didn’t so I left it, but the key sentence would have been that he would have ended up in the Tower Bar, moving on to the stool that his father had been occupying all his life, so that would have been a cyclical, mythic kind of thing.”

There's an optimism to Francie's character that doesn't seem warranted. "That was always there, people would say 'this guy is really down' but what are they talking about? He's irrepressible, this guy can't be stopped The playfulness is probably what keeps him alive and I think honestly the Irish character has a lot of that, 'if they're gonna laugh at me then I'm going to laugh so mad that I'm gonna freak everybody out!' This guy is the town fucking Deer Hunter, he's too intelligent in a way, somewhere in the back of his mind he knows that this is not fair, it wasn't fair what happened to his father, it wasn't fair what happened to him, there's a moral kind of thing buried in it somewhere."

Advertisement

People have hard times, it doesn't mean they go and chop other people's heads off.

"But did he do that?" McCabe laughs.

He did it in the first book.

"Did he? He did it in the film alright, but you don't know! But I'm glad you went in that direction because there is playfulness, there's a fairytale fabulism about it."

Like the narrator in Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman, where they hit the auld fella in the neck with the bicycle-pump and rob him, or do they? And then go circling around in the purgatory...

"Dante!"

So Flann is a signpost? Francie is in purgatory, circling around in his own head, imagining the whole thing in a jacket with the sleeves tied around the back?

Advertisement

"That has been said by one or two people, and I say ‘but aren't we?’”

Aren’t we only solipsistic constructs in our own heads?

“All that.”

Well, I can’t say if we’re real.

“Neither can I!”

The Big Yaroo is available now on New Island Books