- Culture

- 26 Sep 23

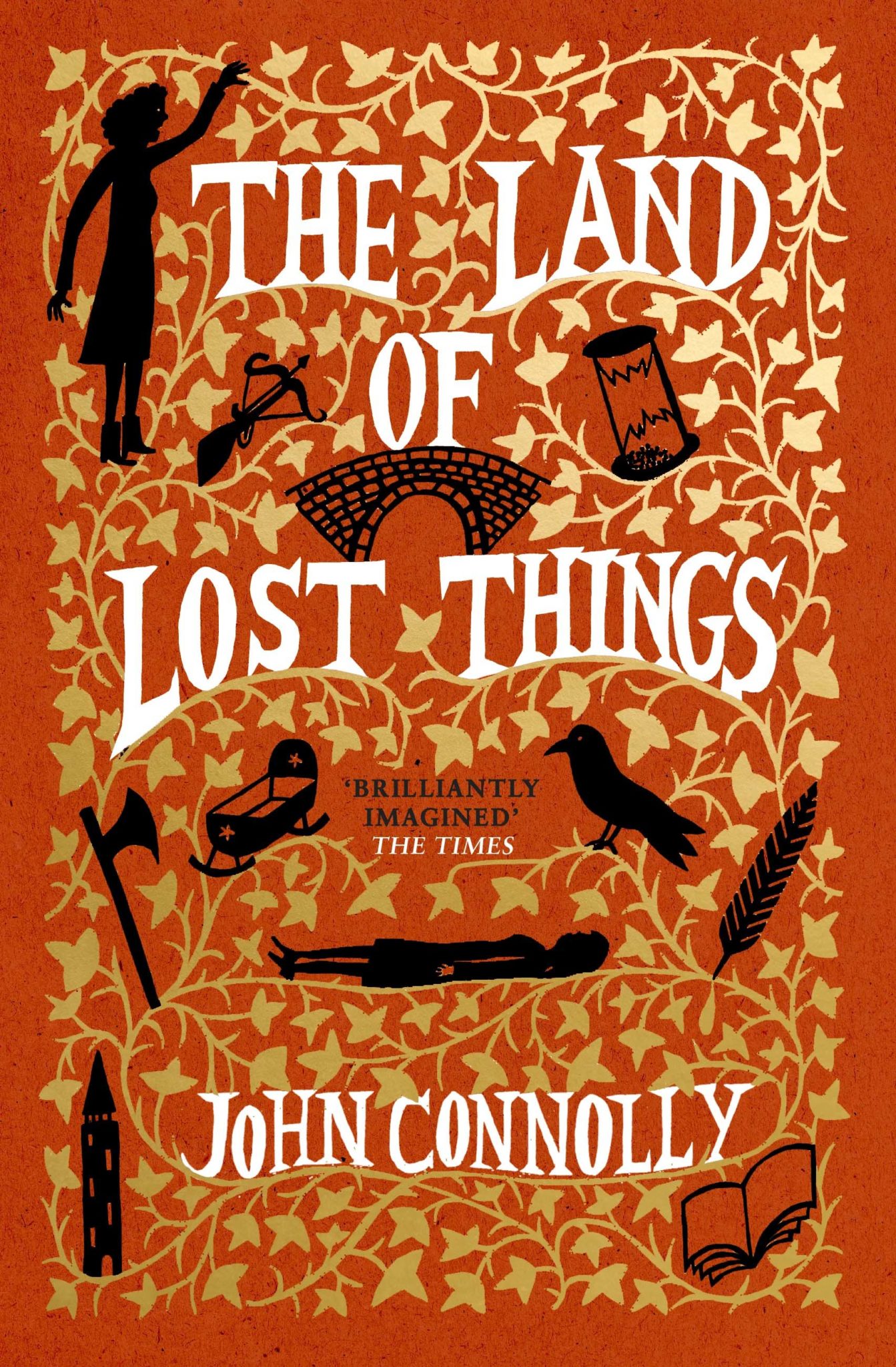

Bestselling author John Connolly on his return to fantasy fiction in The Land Of Lost Things, his cult debut Every Dead Thing, and being influenced by Silence Of The Lambs maestro Thomas Harris.

The latest book from bestselling Irish author John Connolly, The Land Of Lost Things, picks up the thread of his 2006 fantasy novel, The Book Of Lost Things. This time around, an eight-year-old girl, Phoebe, lies in a coma while her mother, Ceres, reads aloud to her some of her favourite fairy stories, in the hope they might resuscitate her.

Ceres find herself compelled to enter an old house on the hospital grounds, which proves something of a portal back to her own childhood, where she encounters witches, giants, and some fearsome old enemies. It’s a gripping tale, which again demonstrates Connolly’s masterful storytelling flair, which is more usually to be found in the Detective Charlier Parker thriller series.

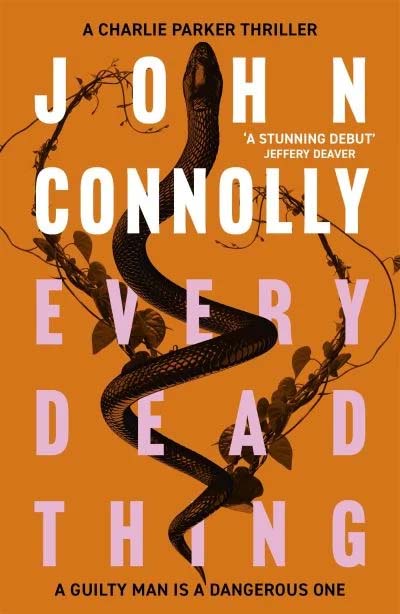

Commencing in 1999 with Every Dead Thing, there are now fully 22 Parker novels, with the most recent installment being last year’s The Furies. It was when writing the screenplay for a possible big screen adaptation of The Book Of Lost Things, that Connolly found himself compelled to revisit the world of the book.

“There was a bit of that about it,” says the affable author. “The previous book was published back in 2006, and my now wife had just moved over from South Africa with her kids. So, for the first time, I went from being a man living in a house all by myself, to having kids around me. One was starting primary school and the other was in secondary school. It seemed to cause me to look back on my own childhood. My parents couldn’t have done more for me, but I was a miserable child, and not much better as an adolescent – I had a terrible adolescence.

“It caused me to go back and revisit that time, because I had these kids around me again. So, it was a really personal book in that sense. I mean, all the books are personal, but that one drew on the death of my father, a childhood plagued by OCD and all kind of things. I wrote it and didn’t think much more about it, apart from the fact that I was very happy with it. Then over the years, it built up kind of an odd readership. It’s a book for adults, and yet it began accruing this readership of teenagers, often ones who were going through something difficult or had lost a parent.

Advertisement

“Suddenly, they found this was a book talking in very open terms about what they were dealing with, whether it was sexual identity, grief, OCD or teenage depression. As the years went by, occasionally I’d write a short story in that vein, but whenever anyone said, ‘Are you gonna write another one?’, I’d say, ‘No’, because I’d said everything I had to say.”

Then, of course, things changed when Connolly was writing the screenplay.

“That just proved that we couldn’t do a screenplay!” he laughs. “All it showed them was that you actually can’t film it. I’d given the book a very gentle polish for its 10th anniversary, but that was the first time I’d gone back and started tearing it apart. I realised that I’d entered a different stage in my life. My kids had left home and I worry about them. My mother is 90 and I worry about her. It’s a phase of middle age, but you just spend a lot of time worrying, because the people around you seem more vulnerable than they were.

“You realise you’re the responsible adult in the room, you become that person. There are days when it weighs on you. You’re not angry, but you can get very frustrated. It can take its toll when things aren’t going well. The first book was about adolescence and I suddenly thought, ‘This is a way for me to explore that again.’ To go back into that world and look at my life through these stories, and this world I’d created in the previous book. It was just the perfect time for it, 17 years later.

“It’s a book about parenthood, more so than the first one. And if I were to do another one, I suspect it would be about old age. There’s probably only one more in me, if I were to go back to it.”

John Connolly. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

John Connolly. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Advertisement

EVERY DEAD THING

Almost 20 years ago, I read Every Dead Thing, which Connolly completed whilst working for The Irish Times. The author travelled to the US to research the novel, in which a serial killer is pursued by Parker. At the time, I wouldn’t have been thinking much more than it was a cool story and a great thriller. Reading The Land Of Lost Things, though, I found myself very affected by the character of Ceres, and the unbelievable pain she endures keeping vigil for a comatose child.

It seems that as we get older, we become more aware of suffering.

“I think grief and vulnerability,” suggests Connolly, “and not just of those around you. Of yourself, as well. I quite like escapism, I don’t see anything wrong with getting out of the world. Books were a source of that for me. But often, as a reader a writer, you’re very conscious that there are moments when you pick up and book, and you think, ‘I’ve always thought that, but I’ve never been able to frame it that way.’ Or often, and more interestingly, it completely changes your perspective on something, because you’re seeing it through other people’s eyes.

“I’ve always found a kind of consolation in that, so I never wanted to write something that I hadn’t invested in personally. Oddly enough, even with a book like Every Dead Thing, the loss of my father fed into it. I think I once said that I’d given every thought I’ve had, and every sin I’ve committed, to a character in a book.”

Every Dead Thing was notably influenced by Thomas Harris, the reclusive US author celebrated for creating Hannibal Lecter, who first appeared in Harris’s 1981 novel Red Dragon and its 1988 follow-up, The Silence Of The Lambs. In an article I wrote just before last Christmas, I made the argument that those two novels were part of five virtually perfect American thrillers from the last 50 years, a list which also included James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia, Donna Tartt’s The Secret History and Cormac McCarthy’s No Country For Old Men.

Advertisement

Would Connolly agree with my choices?

“Apart from dodging it by saying everything is subjective, that’s not a bad list,” he muses. “I’m not an Ellroy fan – we all have our blind spots. In the same way, I’m glad Springsteen is in the world, but I’m not emotionally moved by him. I’m quite happy to go, but I don’t see it."

Certainly, I think the two Harris ones you have to have... Donna Tartt is an interesting one, because is The Secret History a thriller? It certainly wouldn’t have been marketed that way – it was marketed more as a coming of age literary novel.

“It has all the elements, it has a murder and the aftermath. You could argue she’s less interested in the fact of the murder than what happens afterwards, and how it affects the characters. Again, I think No Country For Old Men is a thriller, it just doesn’t end the way a conventional thriller would, it doesn’t give you that kind of resolution. But I don’t think that’s a very bad list, if you were to give it to someone.”

Going back to Every Dead Thing, Connolly acknowledges Harris’s influence.

“With The Silence Of The Lambs, I don’t think anyone had done a piece of mystery fiction quite that way before,” he reflects. “And he could write, and it was fantastic. I remember when Every Dead Thing was published, my nightmare was that Thomas Harris would announced the sequel to The Silence Of The Lambs – and lo and behold, that’s exactly what happened! I thought, ‘Oh balls!’ To be fair, I thought Hannibal was a flawed book, but a very interesting one.”

Even a flawed Harris, though, is more interesting than most novels. Hannibal nicely (well, nastily) teased out the relationship between Lecter and Clarice Starling; offered us one of the great villains of modern American fiction in Mason Verger; and provided some fascinating insight into Lecter’s psychology, even if the ultimate explanation for his pathology – starving German soldiers ate his sister during WW2, ergo he became a cannibal – was risibly simplistic.

Advertisement

“People didn’t like the ending, but I thought it was perfect,” John considers. “It’s a lover’s pursuit, these people can’t do without each other. The reason Clarice Starling keeps going is because of Lecter. Certainly, when it gets to Hannibal Rising and it turns into, ‘Oh, you’re a cannibal because people ate your sister’ – I think psychology is a bit more complex than that!”

John Connolly. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

John Connolly. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.MIXING GENRES

When Every Dead Thing arrived in ’99, the back story of Connolly setting it in the US after researching the book there seemed very exotic – possibly more exotic than it would today, when both international travel and international settings for fiction are more common.

“When people used to travel, they didn’t come back!” says Connolly. “You stayed. Whereas, I was part of a generation where you could go away for x amount of time and then come back. You brought with you this awareness. I was also part of a generation that felt hemmed in by the insularity here, because Ireland in the ‘80s was a pretty grim place to grow up. There wasn’t a lot of optimism; my father had all the optimism taken out of him.

“People like us were being told, ‘Don’t become a writer, go and work for the council’, which I ended up doing. It was partly a reaction to that – you could escape physically to America or Australia, but fiction was an escape. Rather than the stuff that I had to read in school, to read American detective fiction, and odd horror and ghost stories, was a way of getting out of here. I didn’t have much hope of getting out of Ireland; I was completely skill-less.

“When I sat down to write, my instinct was to draw on those things from outside. Because I thought, this place is tired. Now, it’s much more common, and also much more common to mix genres, which is lovely, because you have people now who read graphic novels and they want to apply that to what they’re doing. They can put in all these disparate influences, and maybe it was a little odder then.”

Advertisement

Researching Every Dead Thing was an experience in itself.

“I had a credit card,” recalls Connolly. “I was working for The Irish Times and I kind of maxed it out. I was very lucky – the girl I was going out with at the time was fantastic and she came with me. She had incredible faith in what I was doing and bore half the cost. And also got a holiday out of it, to be fair – it wasn’t all self-sacrifice! (laughs). But it was that thing of, ‘If I’m going to write about these places, I should at least go to the trouble of visiting them and spending a little time.’

“With that first book, part of it was set in Louisiana and part of it was set in Maine. I had worked in Maine very briefly, so that was part of the world that I had a vague knowledge of. Since then, I’ve kept going and we have a house there now, so there’s an engagement with it. I wanted to give Parker a background in a place that I loved, and I really had fallen in love with Maine, because it was a little bit like Ireland… albeit four or five times bigger, with a quarter of the population!”

The Land Of Lost Things is published on September 7.

Read the full Student Special in the current issue of Hot Press – out now: