- Culture

- 01 Mar 23

Jacqueline Crooks: "There was always comradeship between Caribbean and Irish communities in London"

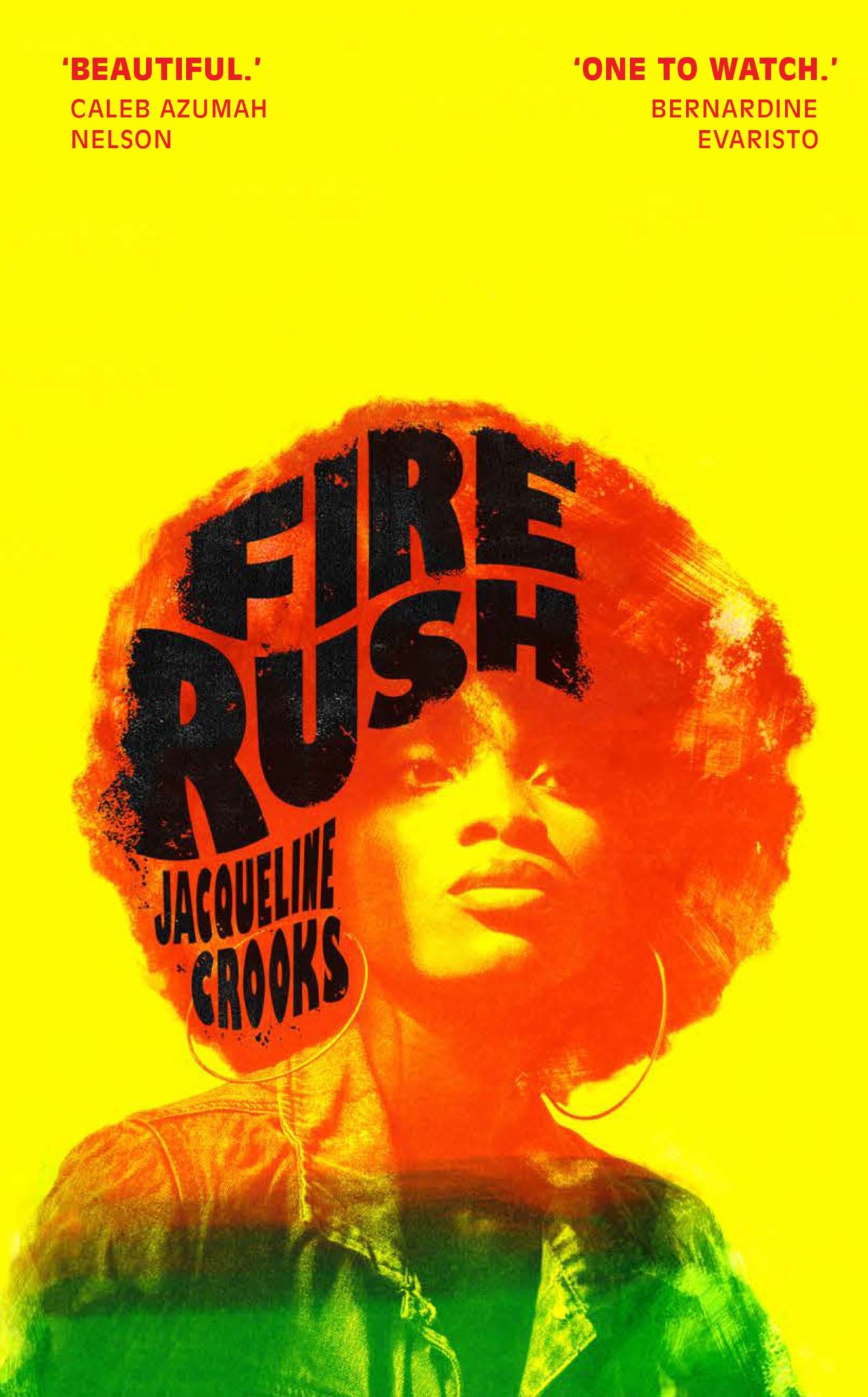

Due to be published on March 2nd, Fire Rush is an explosive novel which transports the reader into culture-fuelled underworlds. Inspired by Jacqueline Crooks’ own experiences, the rich project ignites all the senses as it traverses ‘60s and ‘70s migrant London, Bristol during the anti-police riots and eventually, Jamaica.

Jacqueline Crooks smiles at me from her Camberwell home in southeast London, embracing the busy promotion campaign for her sensory debut novel Fire Rush. Born in Jamaica, the author grew up in London in the ‘60s but her debut pays homage to the land of her DNA. The 59-year-old uses the “liminal space of the migrant between both cultures” to her creative advantage in her explosive project.

“I’m intrigued when people refer to Fire Rush as a debut, because it doesn’t feel like one!” Jacqueline laughs brightly. “The Ice Migration collection was my debut, as far as I’m concerned. Just as much work goes into short stories. I was writing both the short story collection and this novel on-and-off at the same time for 16 years.”

While The Ice Migration featured a collection of stories based on true events and characters; Fire Rush instead looks inwards, at Crooks’ own, often turbulent past. Rooted in events of recent history, it’s a portrait of Black womanhood.

Yamaye lives for the weekend, where she raves at the Crypt, an underground club on the outskirts of London. Everything turns on its head when she falls in love with fellow raver Moose. Her journey of transformation takes Yamaye first to Bristol, where she is caught up in a criminal gang and anti-police riots, and later to Jamaica. Past and present collide with incendiary consequences on the island.

“It’s really writing about my experiences in that world. I’m not afraid to say the occurrences in Fire Rush are closely aligned, because that’s where my impulse to write originated from,” Crooks explains, frankly. “It came from trying to get a deeper understanding of the situation. II feel compelled to write. Coming from a migrant background and a dysfunctional family where I experienced violence, it’s therapy,” Jacqueline adds. “I’m exploring what happened to me, but it’s about what I saw happen to others. It’s about a lost world, really, and the people that inhabited it.”

Yamaye’s mother had gone to Ghana to work when she was just a child, and later passed away, leaving heartbreak behind.

“The way Caribbean communities look at death is so different from English communities, it’s more like how the Irish see it,” Crooks nods. “We don’t actually believe that death is that final thing. We feel that you can commune with the dead, through the lost energy they’ve left behind and things they used to say. Death is an opportunity to party. Everything in Caribbean culture is an opportunity to eat, drink and live. It drives the urgency to celebrate existing. The wake goes on for nine days and nights of storytelling. I wanted to bring this connection of life and death and blur the boundaries between them. We have communication between Yamaye and her mother because it’s one world - one experience.”

Jamaica.

Jamaica.Finding herself in tough environments as a child, Jacqueline was forced to learn how to survive as a teenager while living on the streets and later with a gang. Crooks grew up in Southall and witnessed innocent friends and family members beaten by authorities during the riots. How did Jacqueline escape the darkness?

“By using that same belief in the supernatural presence that you can ask to help you,” she replies. “I’ve done that in my mind, where I asked God to help me out of a situation. It’s that Caribbean belief that there is something out there to assist. That comes through the music, which in our culture is a kind of superpower.”

“Music also saved me. With dub reggae, you don’t so much listen to it as feel it. You embody it. It feels like an ancestral power. Also, people can save you. I couldn’t have gotten out of these situations without a helping hand. You become hyper-vigilant when you come from these marginalised communities,” Crooks concedes. “When you know you’re just a step away from violence, you’re desperate. That can take you over the edge of what you should and shouldn’t do.”

Did Jacqueline feel a burden in terms of writing a prominent Black female character?

“I did feel a huge responsibility, that’s why it took me 16 years!” she laughs. “As much as I’m writing about myself, I want myself to be representative for the other women from that space. We were completely invisible and powerless - not only in the mainstream society but even within our own community because the men had what little power there was. There are so many other women who still aren’t heard.”

One of Yamaye’s closest friends, Rumer, is from an Irish Traveller background who fled an arranged marriage.

“I grew up in Southall, a migrant town. You had Irish, Africans, Caribbeans, and Indians. My friends were from that community,” Jacqueline recalls, warmly. “There was always a sense of comradeship between the Caribbean and the Irish communities. There’s a lot of similarities, so I’ve got a lot of close Irish friends.”

“I felt it important to bring in Rumer because the Irish were there with us, living that migrant experience and experiencing that racism and otherness,” Crooks adds, enthusiastically.

“I didn’t want to make her as large of a character because I felt I don’t like to write about characters that are not within my direct experience. An Irish writer can write that story in a much bigger way. I’ve worked with that community over the last 20 years, and the exclusion is so rife. I wanted to use that to explore the similarities of otherness - how it excludes you. It’s not my story to tell, but I hope this opens a door for another writer from that community,” she notes.

The latter half of the novel is set in Jamaica, where Yamaye hopes to discover her mother’s spirit and parents’ culture in further detail. Crooks herself is a product of the Windrush Generation, a child of those who arrived in the UK between 1948 and 1971 from the Caribbean and helped rebuild the country after World War II.

“I came to London as a baby,” the writer tells me. “I used to go back a lot, but I haven’t been there in over 25 years. It was a yearning for that place that made me set those scenes there. I wanted to bring in that love for my home country in the chapters while writing from a distance. That’s a better way to invoke a place. Yamaye is yearning for Moose as much as the story is about yearning for your home.”

Her lover enters the pages in a blaze of strength, but simultaneous gentleness.

“Moose is an amalgamation of two or three people I knew,” Crooks smiles. “He’s the good guy that I look back at and didn’t stick with, because when you come from dysfunction, you don’t understand what good men are. You don’t understand happiness, so you’re drawn to the darker types. Also, I wanted to show that Black men are loving, they’re ambitious, they have hopes and dreams. I needed to illustrate Black relationships in a positive light, because they’re often shown negatively.”

On the other hand, other men in Yamaye’s life radiate danger.

“It was hard, going back to my experiences,” Crooks continues, quietly. “There was a lot of violence in my childhood and in my family. That’s what you see in my work in the community. It’s not uncommon. It’s almost typical. As much as it was difficult and painful, it was also enlightening. You’re trying to go back through history.”

Southall, London.

Southall, London.When did Jacqueline realise that her home life wasn’t healthy?

“For me, it was school. It was routines, people talking calmly and normalising different behaviours,” she remembers. “Teachers are supposed to be role models. It inspired me to do better and to not live in the same way that my family did. Children from migrant backgrounds, who come from very hard home environments, have adult eyes. Eyes that are much older, like spirits. They can see much more clearly things that shouldn’t be happening and what they need to do to get away from that.”

“I ran away from home when I was 15,” she recalls. “That’s when I got into it with this gang. I went to live in Jamaica, India and Africa for a few months. I didn’t feel as a child that London was home because it was so dysfunctional. I always felt like I needed to get out and find my place in the world. To me, I felt safe with the gang.”

“That’s the awful thing, the gang was a better alternative to my home environment,” Jacqueline laments.

“Initially, they were protecting me and providing me with a home. The thing that saves you can be the thing that then turns against you. The gang became exploitative. But also, they were incredibly kind to other people as well as myself at some points. I didn’t want to demonise them completely because there was a lot of good. Writing this book is my way of making peace with everything.”

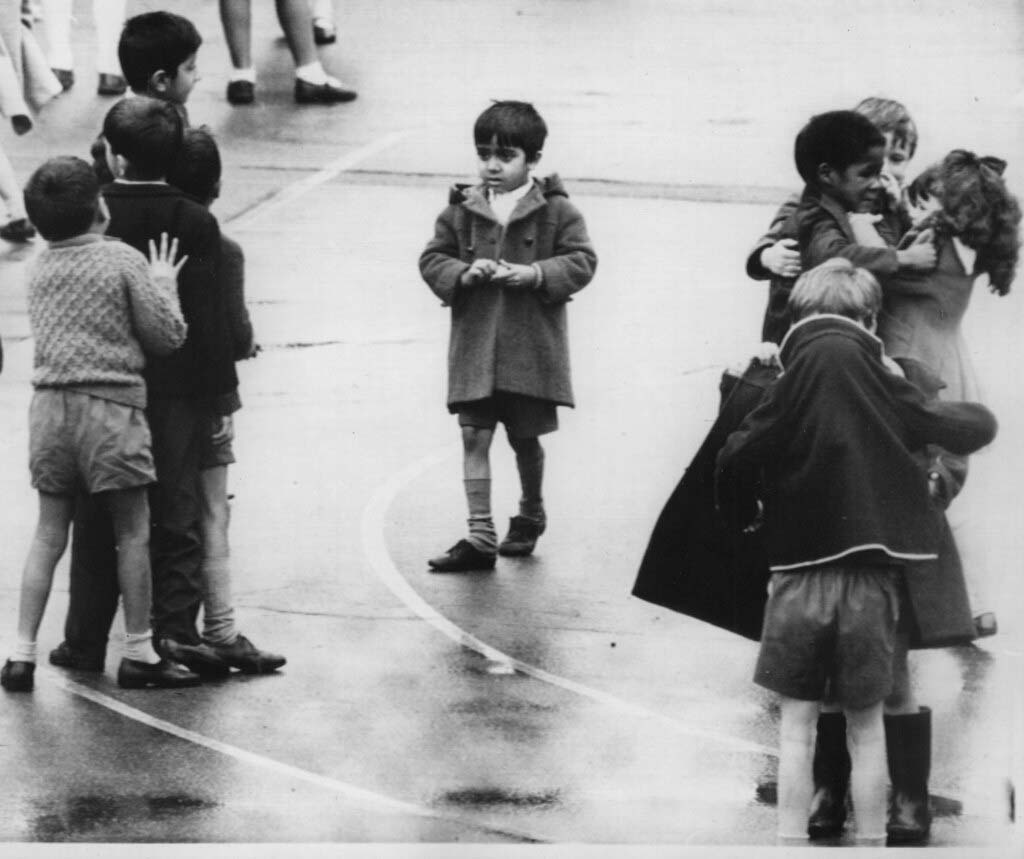

Southall schoolchildren in the 1960s.

Southall schoolchildren in the 1960s.Fire Rush shines a light on how inviting cultures to share with the people they join can only spread a rich tapestry of recipes, storytelling, clothes and language.

“I see it as a form of gaslighting, denying what we brought,” Crooks muses. “If you look back at the ‘70s, our style still carries forward to this day. Also, the language that my grandmother was using, youth and wider communities are now speaking it. It came from Jamaican vernacular. It’s almost trying to push away the value we had on art. My grandma would laugh if she could hear those words being used in 2023.

“More than anything, I want the communities from that locked world who lived it to connect with Fire Rush, and to see themselves,” she smiles.

Fire Rush will be published on March 2nd via Jonathan Cape.

Hot Press' new issue, starring Inhaler and The Academic, is out now.

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 25 Oct 23

Iconic Shaft star Richard Roundtree dies aged 81

- Film And TV

- 12 Apr 23

Nokia ringtone compilation honours late composer Ryuichi Sakamoto

RELATED

- Culture

- 04 Apr 23

Bowie's manager claims Ziggy Stardust comeback tour was planned

- Culture

- 24 Jun 22

Dea Matrona to take to Dublin City's Aloft rooftop next week

- Culture

- 10 Jun 22

Dea Matrona to perform Live @ Aloft show in the Liberties

- Culture

- 14 Oct 25