- Culture

- 30 Jan 20

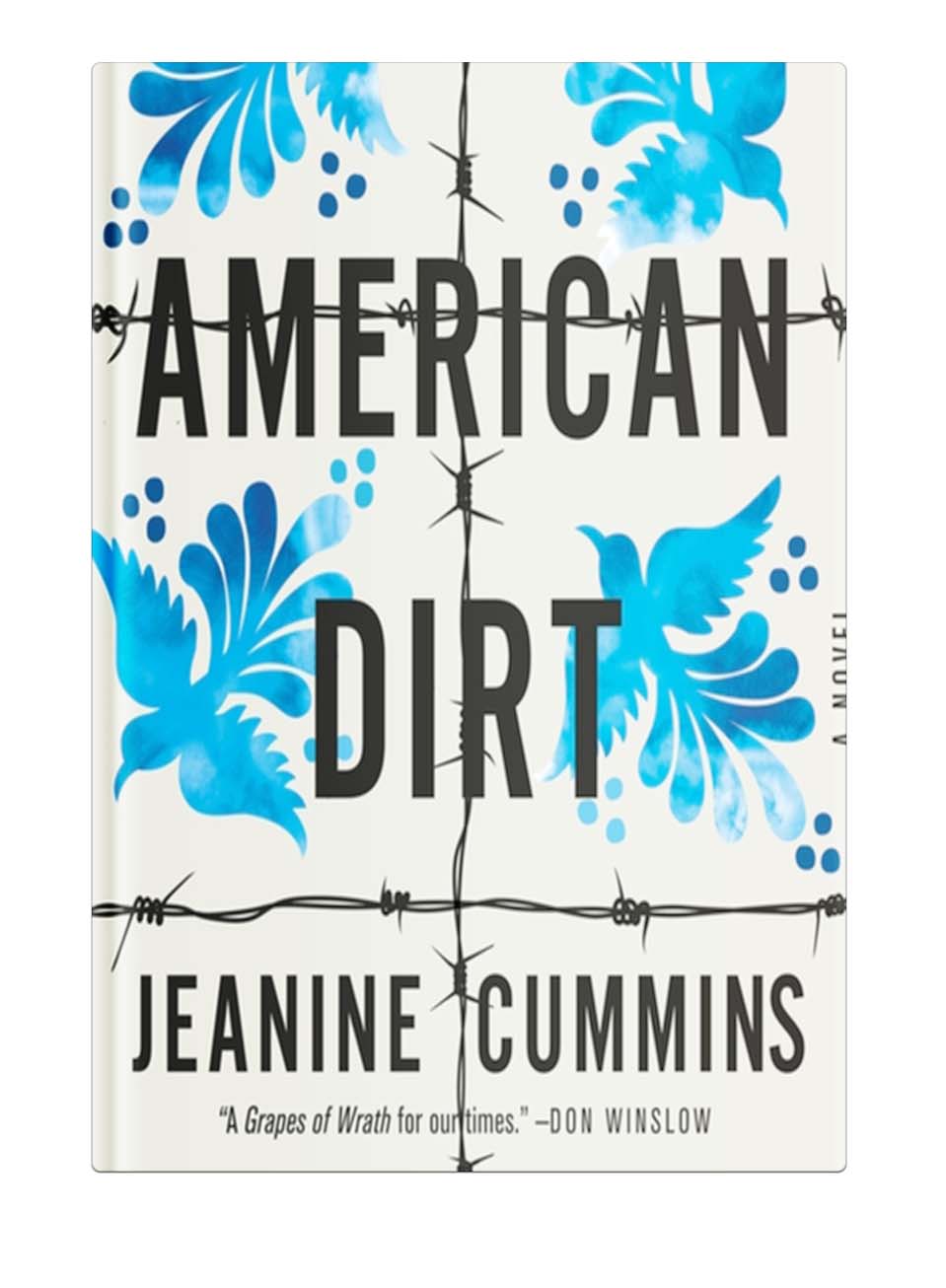

American Dirt is already shaping up to be one of the books of 2020. By setting out to humanise the plight of migrants crossing the US-Mexico border, author Jeanine Cummins has opened up a dialogue that has the potential to shape how people will vote in what promises to be a brutal Presidential election.

Timing is everything. American Dirt is Jeanine Cummins’ fourth novel – and it has struck a chord like nothing she has ever written before.

“In 2013, when I decided to write a book about migrants, I didn’t expect people to care so deeply,” Jeanine explains. “That was way before the issue was in the national zeitgeist. But even since it’s become a hot button issue, the conversation tends to be incredibly superficial in the U.S. I didn’t know if a novel about migrants would resonate – so it’s tremendously gratifying to see the response.” Resonate is putting it mildly. American Dirt has been greeted with international acclaim, including rave reviews from literary giants like Stephen King and Don Winslow. Lauded as a Grapes Of Wrath for the modern age, the gripping novel follows a middle-class Mexican woman and her son, who find themselves on the migrant trail to the US border, after surviving a massacre carried out by a local drug cartel.

Cummins begins the book with a letter to the reader. “In 2017, a migrant died every twenty-one hours along the United States-Mexico border. That number does not include the many migrants who simply disappear each year.” It is a shocking revelation. “But,” she adds, “statistics cannot conjure individual human beings.”

By telling the compelling story of mother-and-son protagonists Lydia and Luca, Cummins aims to humanise the migrant crisis for middle American readers. “These characters happen to be Mexican and Central American, but the whole point of the book is that they could be anyone,” she tells me. “They could be from Syria or California or Australia. We could all find ourselves in Lydia’s shoes in these uncertain times.”

Advertisement

Cummins observes that the conversation about immigration has been marked by a singular lack of humanity. “Even in 2013, before Trump and the resurgence of casual racism, I had this sense of growing unease about how Latino people, and specifically Latino migrants, were being portrayed in the media and popular culture,” she explains. "On the right, there’s this insane caricature of the violent mob, like the narcos we see on Netflix – scary people who are coming here to deal drugs, rape our women and steal our healthcare. Then, on the left, there’s this equally simplistic and unrealistic characterisation of migrants as these impoverished, illiterate, rural people who need us to save them, because we have this saviour complex on the left. In neither narrative are we recognising that they’re actually just people. “I felt there was an opening there to speak to the hearts of people, and remind them that migrants are just like them,” she continues. “They love their kids too.”

Violent Men

The inspiration for the book came, in part at least, from personal experience. Jeanine’s husband, an Irish immigrant, lived undocumented in the US for years before they married. She is well aware that his experience was incredibly different to, and more privileged than, what people from Honduras or Guatemala, riding La Bestia (a treacherous migrant train journey) have to endure. But still...

“He endured a decade of this terrifying situation of living as an undocumented person,” she says. “But he was a white undocumented person, a native English speaker, and he had all the privilege of being a member of arguably the most beloved immigrant group in this country. People here could not love the Irish more, which is kind of crazy when you look back a couple of generations, and see how reviled they were. This is all so short-sighted. W’re going to hate someone else next. It just happens to be the migrants at the southern border now.”

It took five years for Cummins to research American Dirt. She travelled extensively on both sides of the US-Mexico border, visiting shelters for migrants, orphanages and desayunadores (breakfast soup kitchens).

“I endeavoured to meet migrants, to understand the real conditions that they’re facing,” Cummins says. “But I was also there to meet the people who have given their lives to serving migrants and protecting vulnerable people on the borderlands.”

Advertisement

Cummins’ engagement with the plight of migrants also stems from a lifelong interest in the universal nature of trauma. Her first book, A Rip In Heaven, told the story of her own family’s tragedy. In 1991, a group of men raped her two cousins and beat her brother, before throwing them off a bridge into the Mississippi River. Her brother was the only survivor.

“I wrote that book because I felt so angry that the story of my family’s grief had been stolen by these men,” she explains. “They were convicted of their crimes and they were on death row – and then, suddenly, everybody wanted to do a documentary on them, and give them a platform to proclaim their innocence. My cousins had been demoted to a footnote in that story.

“There are so many violent, macho stories about narcos out there,” she continues. “I’m interested in taking the story away from violent men and giving it to the women and children, and in telling the tale of what it feels like to be living in that trauma. That’s the unusual thing about this book. That’s why people are paying attention.”

Moral Obligation

In an era in which identity politics are at the forefront of public discourse, however, Cummins’ decision to tell the story of the migrant trail has sparked criticism. In an author’s note at the end of the novel, she remarks that she “wished someone slightly browner” would have written it.

“I had, and still have, a lot of fear about being the person to tell this story,” she tells me. “There’s been plenty of debate about whether it was my right to do so. I identify as a Latina person, and Spanish was my first language. But my identity is something I have struggled with my entire life: I’m not brown enough. And now, because of this book, I’m being called to account for myself in ways that are impossible to do. I cannot change who I am. I am a person of Latino heritage, but I’m also white. In some ways, I feel like I’m marginalised from both ends.”

Cummins agrees that there is a danger of fiction becoming horribly circumscribed by what one is ‘allowed’ to write.

Advertisement

“So many writers right now are afraid,” she argues. “This ‘cancel culture’ thing is pervasive right now. If someone decides you’re stepping out of your lane, the attack is coming. The tenor of that conversation is so vicious that people don’t even want to risk it, because you’re really sticking your neck out.

“I understand where this movement comes from, and the need to be fiercely protective of representation,” she continues. “But when we chase white writers away from engaging with these topics, we’re just letting them off the hook. I deeply believe that every person in this country has a moral obligation to engage with these stories.

“So, if I have a voice, and I can use that voice to try to spark a conversation in this country, that may open up a deeper dialogue in the middle-class populace, why not be a bridge in that way?”

With American Dirt being published at the start of an election year, that conversation is likely to be timely.

“I’ve often said that the reason we can’t get any traction when we talk about immigration in this country is because the language is so problematic,” she notes. “As soon as you open your mouth and choose your label, it’s like sticking a flag in the ground: migrants, aliens, undocumented, illegal. So, through the great magic of fiction, we’re stripping the labels off, and getting down to the intimate level of humanity.

Advertisement

“It’s a great moment for me as a writer, to know that, in an election year, book clubs will be sitting down to look at this book together,” she smiles. “A group of women, sitting around a dining room table in Kansas, who have probably never had this conversation before, can begin without having to choose a label. It’s my tremendous hope that this story might render empathy in some readers who haven’t thought deeply about this before – especially in an election year.

“Because then we can then take that empathy to the ballot box.”

• American Dirt is out now.