- Culture

- 21 Oct 22

Mohsin Hamid: "There’s an important power in imagining being someone else. There’s something fertile about that transgression"

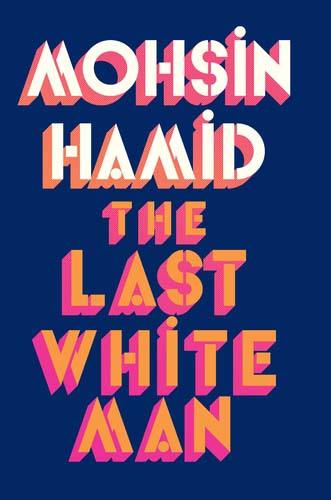

"One morning Anders, a white man, woke up to find he had turned a deep and undeniable brown”: so begins the latest offering from best-selling writer Mohsin Hamid. Subsequently, the powerful novel takes the reader on a journey of introspective reckoning, generational conflict, grief, love and loss. Photo: JIllian Edelstein.

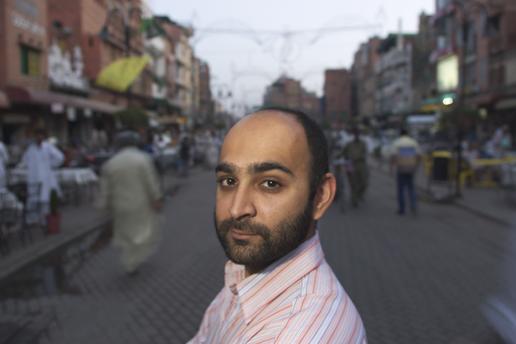

Never one to shy away from difficult, prickly topics (migration, Islamophobia and extreme forms of religion, to name but a few), Pakistani-born writer Mohsin Hamid has carved a name for himself over the Past 15 years as someone with a distinctive voice.

Combining his access to elite spaces of Western culture (Harvard, Princeton) with the experience of being raised in a former British colony, Hamid has used his ‘hybridised’ lives to unlock new literary terrain.

The author has had a busy month promoting his fifth novel, The Last White Man. The follow-up to 2019’s Exit West tells a story of love, loss, family and rediscovery in a time of unsettling change, using race transformation as a starting point. Was he nervous about the response to the book, given how polarised a climate we’re in?

“It’s hard to know what the reaction has been overall,” says Hamid, sitting in a plush hotel near Westminster Abbey. “I write books that are very open to being read in multiple different ways. I treat any reader’s response as that individual’s take, but I think it’s been encouraging. People seem to have found something of value in it. I avoid reviews. My agent and editor and sometimes my wife, Zahra, will tell me if there’s an interesting take in one, but it can be a jangly experience to be confronted with them.

“One doesn’t want any book to disappear unnoticed. The Reluctant Fundamentalist in 2007 was interesting. There was a huge book tour in the US when it came out. But in the UK, it went under the radar for some months. Slowly, it built and built until it peaked about 12 months in, where sales stayed for a very long time. In a way, that would be the preferred method of delivering a book – that it spreads by word of mouth. Sometimes there’s a book that immediately does very well, and others sneakily find their way to readers.”

It should be emphasised that Mohsin’s latest novel, The Last White Man, is not solely about race at all, nor is it a positive slant on what might happen if white people disappeared altogether. Releasing a book with that title alone is a brave move.

“I’m nervous. I never want to be at the centre of controversy,” the author admits. “Particularly when one has spent a lot of time in Pakistan, where I spent almost half my life, you recognise that there can be a price to saying things. Speech is never really free. We hope that it is, and we support the idea, but throughout history and every day, there are writers all over the world experiencing imprisonment or much worse. I certainly don’t court hostility. When I deal with these sorts of topics, I try to deal with them as respectfully as I can.”

In August, a horrific incident saw Indian-born British-American author Salman Rushie attacked onstage in New York. He had been sentenced to death in Iran in 1988 for alleged blasphemy in his book The Satanic Verses. For Hamid, writing about Muslim experience post-9/11 could have been just as divisive, but the tale of a Pakistani Princeton graduate, whose life as a Wall Street high-flyer starts to fall apart after the terrorist attack, turned him into an international sensation.

“In TRF, it wasn’t my intention to mock people who had suffered in 9/11,” Mohsin explains. “Even though the character of Changez initially has some unexplained desire to smile at the terrorist attacks, the book isn’t doing that. That isn’t to say that I think mockery is something that should be banned or denied. In The Last White Man, it sort of ventures into the area of race. Exit West was about migration, another sensitive topic, but a novel about migration is less likely to upset you than one which deals with 9/11 or race.

“This novel comes into tricky spaces in the world, but I don’t think that writers need to avoid going there. I wanted to dive into recent history in terms of Brexit, Trump and the rise of white nationalism, partly because I’ve lived in the US collectively longer than Pakistan. That these places are going to become hostile to people of particular backgrounds is something I perceive very personally.”

Writing about terrorism is particularly prickly with regard to the US, where white nationalism consistently fails to be categorised as domestic terrorism.

“It’s an interesting question: what are we permitted to speak about?” Hamid nods. “There are often obvious things in terms of dictatorships, who don’t let you talk about religious symbols, for example. But there are also other ways in which we are encouraged not to speak about things, like certain national narratives. Particularly in those initial years after 9/11; the idea that there could be some connection – not a justification – between this terrorism and violence the US perpetrates abroad was something people just didn’t want to talk about.”

The Reluctant Fundamentalist motion picture, starring Riz Ahmed (2012).

The Reluctant Fundamentalist motion picture, starring Riz Ahmed (2012).MONGRELISED, HYBRIDISED PERSON

For many of us, that link was impossible to ignore.

“There’s this desire,” he adds, “to treat white nationalist terrorism in a fundamentally different sense. It’s seen as something born of insanity. We also say that anti-US terrorism has no connection to US actions. In both instances, we don’t investigate what’s happening. It suggests there are some narratives underneath that really don’t want to be disturbed. Every tradition has its own versions.”

Ireland has its own dubious narratives – like the tendency to directly compare our oppression by Britain to the pain of other races. Over the past five years, the Irish Slave myth has gone viral, comparing the experiences of black enslaved people in the Caribbean and US to that of Irish indentured servants. In reality, many Irish people in the Caribbean were slave owners.

“Ireland is very interesting to me,” Mohsin replies. “It’s the first British colony, in a way. It has both a colonial and post-colonial experience, which is a lot like Pakistan. Also, it has a history of emigration to countries like the United States, where the Irish, Italians and Jews weren’t thought of as white initially. They were a different character, a different ‘type’ to the Protestant white people. Over time, due to assimilation into this notion of whiteness, it flips. Ireland and the Irish are innately understanding of the colonial and immigrant experience.

“On the other side, it understands the push towards the West, the dispossession of land from native tribes, slavery and all of these institutions. Almost more than any other Western country I can think of, Ireland straddles both sides of these questions of race and colonialism. That’s potentially why Irish literature is so fertile. Considering the size of your population, Irish writers have produced an incredible amount of books.”

While Ireland was victim to British colonialism, that doesn’t grant our people the right to claim an understanding of the struggles of predominantly Black and Brown communities. Support for Palestinian people facing apartheid in Israel may be passionate, but the Irish stood on Black people in the US to rise above their given status, later assimilating into the brutal police forces of New York and Chicago.

“If one takes one’s history and claims that it removes the need to empathise with those who are suffering today – that I and my people suffered in the past so these people don’t have a claim on my empathy – that is a very dangerous move,” says Hamid. “The alternative is just to say that, in a sense, everyone has at some point experienced subjugation. There’s a way to identify with people all over the world who have experienced that, and to have the difficult conversations in one’s own community. In an Irish context, how do we square support for the Palestinians with racist policing in America? How do you have these conversations?”

At its heart, TLWM is a novel about seeing, being seen and letting go. The loss of privilege that comes from being perceived as white, and no longer being able to view the world from within whiteness, are among the anxieties examined. Would he have put pen to paper had he not had periods of his life in such differing cultures?

“I might not have been a writer if I hadn’t moved around that much,” he says. “I was definitely a little fantasist when I was a child in California. I would see colours in our black and white TV. I played make-believe games. I came back to Pakistan in 1980, and in those days there wasn’t any internet and very little television available. Cinema rarely showed foreign films, so I was suddenly very cut off from the media culture of America and the West.

“I read lots of books, and remained in this imaginary world of my own. That impulse was always there, but it could have easily turned into something other than writing. When I went back to the States, I discovered these creative writing classes in college at Princeton. I wound up taking one with Joyce Carol Oates and Toni Morrison. It was cosmic good fortune to get those teachers.”

Credit: Ed Kashi.

Credit: Ed Kashi.Undoubtedly, he felt inspired.

“It was also the first time that I thought someone like me could be a writer,” continues Hamid. “I thought authors were in another category of person. Had I never left Pakistan and lived a different life, I suspect the need to be a writer would have been much less. Because of moving countries and becoming a mongrelised, hybridised person, I can sort of pass in Pakistan as reasonably Pakistani, and perhaps in America and Britain I can do the same.

“I’m a slightly different kind of person. When that’s the case, you become very sensitive to moods that suggest only a pure person of the local tribe is desirable. I’m very aware of ethno-nationalistic or religious nationalistic impulses in any one of my three homes. It seemed to suggest that people like me didn’t really have a place. All of that has impacted my words.”

Hamid has found success through the publishing centres of New York and London, with the support of a global audience to which he has tailored his writing. However, his novels have also been criticised for providing a limited representation of homogenous groups. In his third book, How To Get Filthy Rich In Rising Asia, Hamid does not reference Lahore, Pakistan, or even Asia specifically. Similarly, The Last White Man lists no local places or identifiable factors.

“I think it’s understandable, though I don’t necessarily agree with it,” Mohsin says of the critiicism. “Certain voices have been marginalised in storytelling, publishing, television and film. There’s an impulse for a certain representational storytelling to ‘rectify’ that injustice, which I fully support. The need for greater representation and the suspicions around appropriation or exploiting the stories of others are entirely justified.”

RACE IS AN IMAGINARY THING

That said, Hamid stands by the right of the author to imagine different worlds into being.

“There’s a very important power in imagining being someone else,” he adds. “I think the ‘self’ we inhabit is a performance, but the imagination questions that. What would it be like for me to be something other than a straight person, or Pakistani, or a man? What if I was born 300 years ago? What if I was put in this situation? That aspect of literature is also important. When human beings imagine being others, there’s something very fertile about that transgression.”

He alludes back to the novel.

“In this book, the interiority comes from these four main characters who think of themselves as white,” Hamid continues, referring to Anders, his lover Oona and their parents, who all have differing reactions to white people in their communities waking up with dark skin. “They’re not in Pakistan and they’re not all men. They’re not my age or of my background. I do believe that writers should be able to write from another point of view. But if you write about people who you can’t identify as, you’re open to criticism. Then it becomes a question of intent and craft. I’m going to try to be these people, and the reader can judge to what extent the writing is revealing of my own bias and incapacities as a writer. A novel is punctuation marks and letters on a white page. The reader is the casting director, the cinematographer, the location scout.

“When one writes a novel that is very open to readers imagining in their own way, you’re open to readers saying you’re too ambiguous. In my non-fiction, I do say my opinions on certain topics. Race is an imaginary thing. We invented it years ago, acted like races exist and then, by proxy, they did exist. Some people are uncomfortable with what they saw when they imagined the book, but that’s not bad, it’s actually a useful tool.”

For some, The Last White Man may call to mind the theory of Great Replacement; a white nationalist far-right conspiracy. The fear is that white European populations at large are being demographically and culturally replaced with non-white peoples from the Global South through mass migration, demographic growth and a drop in the birth rate of white Europeans. In the novel, those who saw themselves as white have to reckon with the discrimination of others – and often themselves – when their skin colour changes. Oona’s mother is a conspiracy theorist drawn down the QAnon rabbit hole, supporting white militia groups who try to drive dark-skinned people out.

“A novel is an invitation into a bizarre place,” says Mohsin. “Novels aren’t simple things, so you can’t apply a simple explanation of, ‘If there were no white people, everything would be fine’. To what extent are all of us white people? Is the book about the erasure of whiteness or the universality of it? Who knows? It’s up to you. Every generation does face a great replacement. We get old and we die and the young are born and grow up. That creates a certain anxiety that our way of the world will be gone. The truth is: it will be. One thing the novel tackles is love between generations as a way of transcending that loss.”

• The Last White Man is out now, published by Penguin.

Read more interviews in the new issue of Hot Press, out now.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 11 Sep 21

Nine Eleven: The World Would Never Be The Same Again – Or Would It?

- Culture

- 16 Jan 26

TradFest South Dublin 2026 launched at Tallaght Stadium

- Opinion

- 16 Jan 26

Irish humanitarian Seán Binder acquitted on all charges

RELATED

- Culture

- 15 Jan 26

The Complex announces official closure

- Culture

- 12 Jan 26