- Culture

- 29 Mar 23

Nicole Flattery on new novel Nothing Special: "Andy Warhol was so intensely aware of his own image, which he created from scratch"

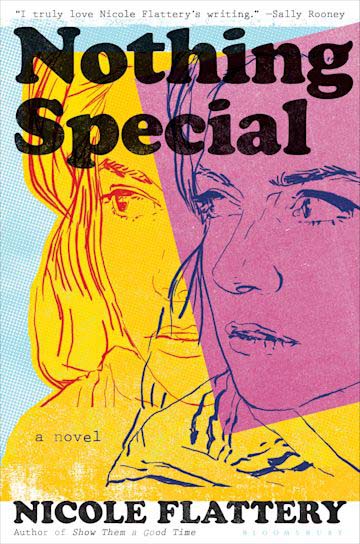

Award-winning Irish author Nicole Flattery discusses her debut novel Nothing Special, which brilliantly explores the fascinating world of Andy Warhol’s Factory. Portraits: Miguel Ruiz.

Mullingar author Nicole Flattery earned rave critical notices for her debut story collection Show Them A Good Time, published in 2019. As a result, expectations are at fever pitch for her first novel Nothing Special. It tells the story of Mae, a disaffected high school dropout, who becomes immersed in the world of Andy Warhol’s Factory, and thus gets to observe first hand the rarefied world of ’60s New York bohemia.

Mae and another girl, Shelley, are hired to transcribe Warhol’s interviews with actor Robert Olivo, aka Ondine, which the artist eventually turned into the literary work a, A Novel. Together, Mae and Shelley get to experience both the glamour of the Factory scene and its darker aspects, making for a compelling portrait of a period that has enduring pop cultural fascination and appeal.

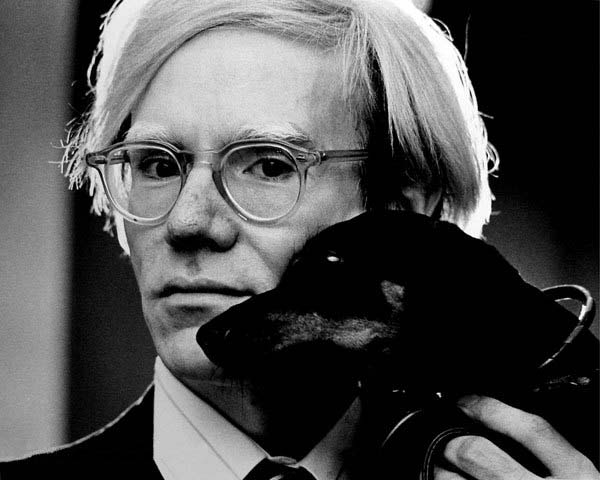

Andy Warhol by Jack Mitchell.

Andy Warhol by Jack Mitchell.Was it an era that always held an attraction for Flattery?

“It didn’t actually,” she replies, sitting in Dublin’s Brooks Hotel. “One of the fine things about this book is I got to do so much research. I like a lot of films from the ’60s, and Warhol is sometimes referenced as an influential film guy. Also, I’ve seen exhibitions, and I knew about Edie Sedgwick and listened to The Velvet Underground. But I wasn’t super into it. I hadn’t read any of the books. I felt lucky, because I chose a subject I could be more interested in.

“I was writing it for four years and I kept discovering new things. Warhol himself is such a layered, complex figure that every book was giving me a new vantage point. It is a very captivating time, and in comparison to how we live now, creatively it was free. I can see why people are consistently fascinated – it doesn’t get less fascinating when you look into it.”

With Nothing Special told from Mae’s perspective, Nicole says one of the main challenges was capturing an authentic adolescent voice.

“You’re trying to get back to what it feels like to be 16 or 17,” she reflects. “It’s a time when you’re very unsure of yourself and have no idea who you are. I was thinking, ‘Obviously it’s the Factory and you have to write party scenes’. Those parties can be so glamorous, and I was going, ‘But the girls aren’t going to be glamorous. They’re going to be there observing these things, not really participating’.

“At the same time, they would want to be in the middle of it, in an almost needy way. I thought that was interesting approach, and I know teenage girls did work in the Factory – the two characters are sort of based on a picture I found. The ’60s were supposed to be a liberating time for teenagers: it was when youth really came into play. Particularly as a woman, I wondered how it felt to be a part of that.

“You were constantly being told you’ve never had so many opportunities or so much freedom – it must have been stifling as well as interesting. Those were things I wanted to explore, as well as getting the voice right. It was that teenage voice that’s quite brash, but also unsure and constantly correcting itself.”

NIcole Flattery. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

NIcole Flattery. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.SUCH A FUNNY BOOK

Mae’s authorial voice actually recalls the works of Joan Didion – stylish but with a neutral, cool, take on what’s unfolding around her. Alternating between her reflections on her Factory adventures and her current existence in humdrum middle age, the narrative also has the sweep of classic 19th century authors like Flaubert and Balzac.

Indeed, those novelists can be considered the rock stars of the form, given that they were the first to fully capture the ups and downs, the excitement and chronic disillusionments of life.

“That was my main intention,” agrees Nicole. “I was giving this talk to creative writing students, and I was saying that my main advice when you’re writing a novel, is that you have to write a book that you want to read. Otherwise, you’ll lose interest in it after two years.

“I love books that show you a whole life, and I knew that I wanted to see her as an older person after being in the Factory. I’d imagine it was a very discombobulating experience, because to some extent, your experience was over-ridden by history. So to stand back and say, ‘That’s not what it was like for me’ – I find that disparity so interesting.”

Complicating it, of course, was Warhol’s crafting of his own mythology.

“He was so intensely aware of his own image,” nods Flattery. “He created it completely from scratch. Even the photos that you think seem unguarded, they’re all controlled – he was a control freak. That’s what makes it so hard to break down the whole Factory scene, particularly when so many other people have their takes as well. If it was bad, or not good, it’s almost like breaking down a cult or something.

“In order to understand that it wasn’t good for you, or someone else, you have to go back and readjust your whole memory. People don’t want to do that, they want to remember it as a happy time. In the Velvet Underground documentary, the film critic Amy Taubin has one line where she says, ‘The Factory wasn’t a great place to be a woman’. I was like, ‘That is absolutely true’.

Joan Didion.

Joan Didion.“It was intensely competitive, and you were constantly being judged on your appearance, or what you could bring to a party, or what outrageous behaviour you were capable of. I had finished the book by the time I saw the film, and I was like, ‘Thank god she didn’t come out and say it was a fantastic place to be a woman!’”

Indeed, Warhol was eventually shot and injured by the radical feminist Valerie Solanas, famed for creating the SCUM Manifesto. It’s quite something to imagine Solanas – who passed away in 1988 – alive today and tweeting her take on the culture wars.

“I actually read SCUM Manifesto years ago,” says Nicole. “I feel like maybe we’re losing our sense of humour generally across the board, but that’s such a funny book, and I don’t think she meant half of it to be taken seriously. It was all written in jest. About three or four years ago, she got a New York Times obituary as a reconsidered female figure. I was like, ‘She still shot someone though!’ But she’s a fascinating person.”

In writing Nothing Special, Flattery could clearly see the complexity of individuals like Warhol and Solanas.

“Warhol was probably a genius,” she considers. “And also probably a very selfish narcissist. But are they crimes? I don’t know. So I ended up seeing a very human side of both of them. That’s the only way you can write a book.”

Unfortunately, these days, the room for teasing out people’s nuances is too often lost in the public discourse.

“I remember going around the room with my friends one time,” laughs Nicole, “and we all had to name someone we’d be devastated to see cancelled! Someone said David Lynch and I agreed with that. I don’t think he would, but when you really like someone, you get that little fear something could happen. But then again, I obviously think Polanski is reprehensible, but I still think Chinatown and Repulsion are great films. That’s when it’s very difficult to try and figure out how you feel.”

I MISS NOT KNOWING

Talk turns to the anticipation around Nothing Special and its Dublin launch – at which point I realise I haven’t been in a bookstore in years, largely thanks to Kindle. It all makes a drastic change from my adolescence, when my favourite way to spend a Saturday was to get the bus into the city centre, and browse around book and record stores before going to a movie. Nobody had mobiles, and it was blissful. The analogue late ’90s had a lot to recommend it.

“Every so often, I announce to my boyfriend that I want a complete cultural change,” says Nicole, expressing a sentiment that will resonate with many. “I feel so worn out by phones and algorithms. I find a lot of it really dull. I rarely go on there now and find something interesting, whereas five years ago I did. The conversation has deadened so many things. Like, I recently saw Tár and really enjoyed it.

“If I didn’t have my phone, I would have just left the cinema and thought ‘What a great film’, and maybe thought about it on my own. Instead, I got hundreds of articles with people debating every single aspect of it. I’m quite weary of it now. It’s very repetitive and boring, so I want something completely different, but I don’t know what that is.”

It feels like everybody is exhausted by it offline, but social media doesn’t seem able to get beyond it.

“I was writing something about Warhol and the brief was celebrity culture,” says Nicole. “There’s room now for a bit more mystery: every celebrity and actor is super over-exposed. You go on Twitter and see a hundred tweets about Paul Mescal or whatever, and it’s so hard then to go to the cinema and watch that person be another person. I miss not knowing about people, and having to guess.”

• Nothing Special is out now.

The new issue of Hot Press is out now.

RELATED

- Culture

- 21 Jul 25

Warhol and Banksy works to feature at Art and Soul festival near Belfast

- Culture

- 18 Jul 23

Ireland's largest ever Andy Warhol exhibition to open in October

RELATED

- Culture

- 10 Feb 22

Betty Davis, legendary funk trailblazer, dies at 77

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 01 Jul 21

Gottfried Helnwein: “The Roman Catholic Church is the most powerful propaganda machine in history.”

- Film And TV

- 10 Aug 20

Jared Leto to play Andy Warhol in upcoming biopic

- Culture

- 23 Oct 19

Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition comes to Dublin

- Culture

- 30 Oct 18