- Opinion

- 24 Jan 22

Remembering Ashling Murphy, 1998-2022

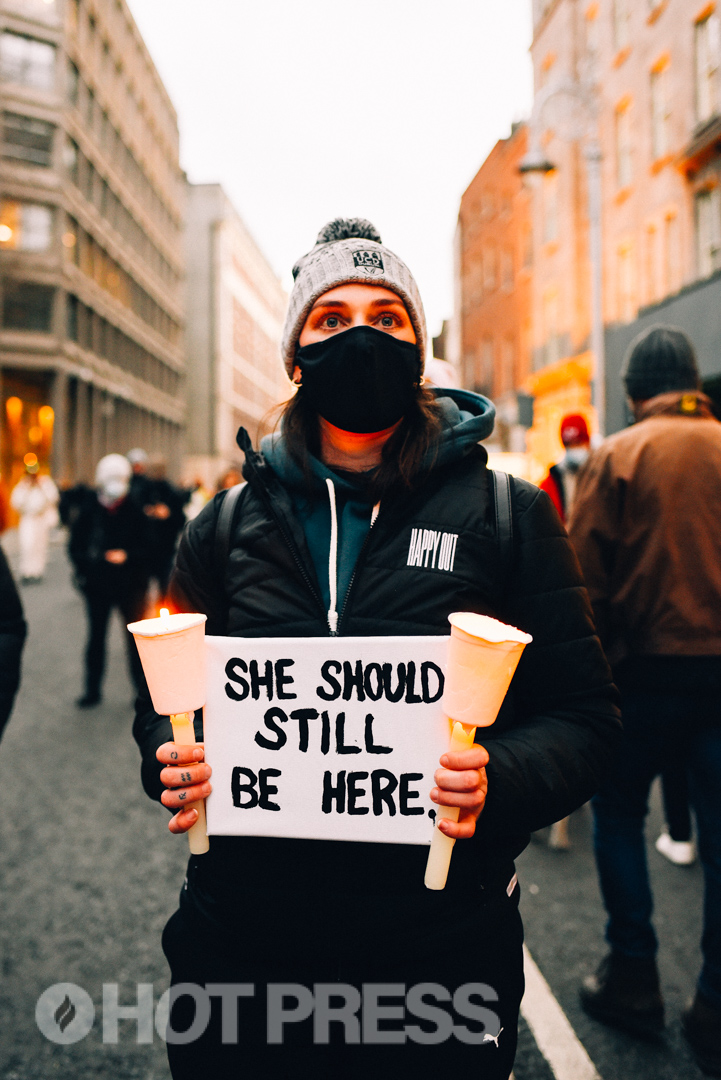

The murder of the young schoolteacher Ashling Murphy in Co. Offaly has sparked an intense period of national mourning – and brought a fresh sense of urgency to the campaign to eliminate violence against women from Irish society...

There are times when language fails. The murder of the young Tullamore national school teacher Ashling Murphy was appalling, vicious, senseless, brutal, abhorrent, beyond the pale of any notion of human decency or civilisation. It was sickening. Heartless. Shocking. Monstrous. Cruel. Unconscionable. Depraved. Barbaric. Malevolence incarnate. It was Evil.

The truth is that I could be here all day and all night, trying my damnedest, and still not get anywhere near describing accurately the scale and depth of the emotions that the family of Ashling Murphy must have experienced over the past week, and which women all over Ireland have been feeling, since the first bulletins delivered the kind of news that no one ever wants to hear: A Young Woman Has Been Murdered in County Offaly.

This was random. In the middle of the afternoon. Close to Ashling Murphy’s home.

It is no wonder that women – young and less young alike – think: it could have been me. Or my sister. My daughter. My mother. My friend. There have been many murders of entirely innocent individuals in Ireland over the past ten years. But this one has struck a deep chord across the country in a very different way.

There have been parallel moments elsewhere. The kidnap, rape and murder, in March 2021, of 33 year-old London-based marketing executive Sarah Everard, by Wayne Couzens, triggered a seismic outpouring of grief in the UK. Couzens was a member of the Metropolitan Police, who worked as a ‘diplomatic protection officer’ and was entitled to carry a gun. That detail understandably added further fuel to the crushing sense of collective outrage: even members of the police force – to whom women have to turn if they are in difficulties or are attacked – can represent a threat to the lives of innocent women.

Sometimes language really does fail.

Vigils in memory of Sarah Everard were held on Clapham Common, on March 13 last year, but these were broken up by the same Metropolitan Police because they were deemed to contravene lockdown restrictions. It was a shocking misjudgement by the forces of law and order, which provided added confirmation of the toxic misogyny which still poisons so many aspects of public life, even in countries that think of themselves as democratic and civilised. Needless to say, it looks all the more disgracefully wrong in the light of the grotesquely elitist party culture that existed in the Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s residence, at No. 10 Downing Street, at that very time, and indeed throughout the imposition of pandemic-related restrictions on the personal freedom of individuals and of communities all over Britain.

The grim and emotionally harrowing saga of Sarah Everard’s murder sparked, in the UK, a fresh awareness of the issue of femicide, and the stark fact that so many women are murdered every year by male perpetrators. There were 241 ‘homicides’ of women in the UK in the year ending March 2019. The vast majority of these were committed by men, very frequently by the ‘partners’ of the murdered women.

Measured on a per capita basis, the figures in Ireland are slightly lower than in the UK. But that statistic offers no release from the reality that the numbers in Ireland are also chilling, with women making up a third of all homicide or ‘manslaughter’ victims. In 2017, 16 women were among the 48 who died violently. In 2021, seven women died in tragic, violent circumstances out of a total of 22.

There is no excuse for it. No rationalisation. No explanation. No defence.

It is our duty as a society to work as hard as we humanly can to find a way of turning the tide, so that it doesn’t continue to happen again and again and again. That is what every sane person wants: an end to the climate of fear. And yes, men have a major part to play in changing the culture – first of all by becoming more educated about sex and sexuality and in particular about the vital importance of consent; and also by doing whatever is necessary to eradicate the putrid instinct that covertly deems violence against any other human being, male or female, acceptable. It isn’t.

I will come back to the issue of anger.

Ashling Murphy vigil at the Leinster House, Dublin. Friday 14th of January 2022. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Ashling Murphy vigil at the Leinster House, Dublin. Friday 14th of January 2022. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.BEYOND DESCRIPTION

At the beginning of a new year, there is a feeling of potential renewal. A hope that things can be better. An optimistic feeling that we might just be able to leave at least some of the horrors and the misery of the past – in whatever form – behind. Of course, in some ways that is bound to be a forlorn hope. Change doesn’t happen on its own. But still, it is part of the human condition to look forward in anticipation of brighter, better days to come. To imagine for example: perhaps this year, women’s right to feel safe on the streets of the places they live in, know and very often love will be given proper respect.

Less than two weeks into the new year, with the murder of Ashling Murphy, that hope has been smashed in the most terrible and heart-breaking way.

It is one of the first and most visceral responses. How would I feel if it had been my sister, my daughter, my mother who was set upon and strangled to death with such contempt for any form of human decency? But of course, it wasn’t a relative of mine. There is a real family involved. A mother and a father. A sister and a brother. Kathleen, Raymond, Amy, Cathal. On them has been inflicted the single most appalling sadness that anyone can ever have to endure: the cruel loss of a loved one in circumstances that must, and do, challenge the belief that we try desperately to hang onto, that human life is worth living and that there is some kind of meaning or purpose to it all. For what purpose could possibly be served by something so monstrously wrong?

It is clear that we should do anything we can to help the family and friends of Ashling Murphy get through the loneliness, hurt and betrayal that they must feel – along with the burning knowledge that their precious Ashling has been stolen from them, and with her almost certainly their long-term capacity for happiness and joy. There is no way around that. All we can do is let them know that they are in our thoughts and in our hearts.

It is, and will be, impossible for anyone outside that devastated, wounded group of ordinary, good, unassuming citizens, to understand the depths of sadness, loss and grief that they will feel individually and collectively. The President of Ireland Michael D. Higgins expressed very well the compassion with which Irish people generally have responded to the tragedy.

“People throughout Ireland,” the President said, “in every generation, have been expressing their shock, grief, anger and upset at the horrific murder of Ashling Murphy.

“This morning I spoke to Ashling’s family to convey, as President on behalf of the people of Ireland, and on behalf of Sabina and myself as parents, my profound sympathy and sorrow and sense of loss that her tragic death has meant to so many, but what in particular it must mean to her mother Kathleen, father Raymond, sister Amy and brother Cathal.

“I sought to convey a sense of how so many parents, families, indeed all of the people of Ireland are thinking of the Murphy family at this very sad time. The loss of Ashling is a loss to all of us, but to her family it is beyond description.

“The outpouring of grief at the death of Ashling shows how we have all been very touched, and it is so exemplary for young and old, to read of all Ashling’s accomplishments during her short but brilliant and generous life.”

He spoke about Ashling’s qualities as a person and about her achievements, in music, in sports and as a teacher. Listening to the stories about her, you get the impression of someone you’d love to have known or worked with.

“It is of crucial importance,” the President added, “that we take this opportunity, as so many people have already done in the short time since Ashling’s death, to reflect on what needs to be done to eliminate violence against women in all its aspects from our society, and how that work can neither be postponed nor begin too early.

“May I suggest to all our people to reflect on all of our actions and attitudes – and indeed those we may have been leaving unchallenged amongst those whom we know – and do all we can to ensure that the society we live in is one where all of our citizens are free to live their lives, participate fully, in an atmosphere that is unencumbered by risks for their safety.”

Michael D Higgins at Áras an Uachtaráin. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Michael D Higgins at Áras an Uachtaráin. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.TARGETED ON SOCIAL MEDIA

These words, spoken by the President, were carefully formed and well chosen. They hit home. On one level, it comes down to something very simple: we need to create a kinder and more compassionate society for all.

There is something else that we should also address before it is too late. As President Higgins said, and as so many women’s groups have also highlighted, the widespread feeling of outrage, shock and revulsion can be a force for good if it is channelled into positive, constructive action of a kind that might challenge – and change – the elements of our culture in which violence against women is somehow seen as less than what it is: criminal behaviour.

In an atmosphere of heightened emotion, we also need to be extremely careful. Given irresponsible free rein on social media, some of the more extreme responses can have the effect of stoking hatred and of putting individuals at risk, in a way that is fundamentally wrong.

Over the past week, in the rush to find a target for people’s anger about what happened to Ashling Murphy, the lives of individuals, and their families, have been placed in danger.

For a day, it was more or less taken as read that a Romanian man was the murderer. He was taken into custody and questioned by the Gardaí and his name became known locally. No responsible newspaper, magazine or broadcaster would even consider publishing a photo of an individual in circumstances like this. And yet his identity and photograph, as well as his own Facebook posts, were circulated widely on social media.

So why are social media companies allowed to facilitate this, and to benefit financially by attracting clicks and comments and what they like to call ‘engagement’ from material that places an individual in the firing line.

As it turned out, this man was entirely innocent. He had nothing whatsoever to do with the murder. But his name and likeness were blithely pinged across more or less every available platform.

Recklessness in relation to the right of any individual to the presumption of innocence makes a mockery of the idea that we have – or can have – a reliable, independent judicial system that protects the fundamental right of everyone living in our jurisdiction to be adjudged innocent until they are proven guilty. The solicitor representing this man has said that, because of direct threats to his life, he has had to go into hiding. That his family have also had to move. That his life has been ruined.

And it is true. So who is going to compensate him? The idea that he should have to chase a bunch of individuals to try to get some kind of relief is absurd. But that is the chicanery that social media companies are typically allowed to get away with. People need to think harder and longer before they post material. It is an individual responsibility not to do anything incendiary: no sensible person would argue against that. But it is the social media companies that must be held accountable. They are the ones generating profit. They should pay for the damage they have done – or allowed to be done – to the man and his family.

Separately, I received a WhatsApp message with a photograph of the new chief suspect, who is also from Eastern Europe, alongside his brother. A single paragraph message was included that purported to give an account of what had taken place over the two days, and the role played by the brother in relation to the tragic events.

The reality is that no one has the slightest clue what might have been happening in conversations between the two men over those two or three days.

There is the suggestion that a suicide attempt was made by the alleged perpetrator. No one knows either how the injuries which put him in hospital came about, whether they were self inflicted or what the intent might have been.

The impression is given in the account attached to the photos that the brother knew exactly what had happened. And that he had become an accessory to the crime after the fact. The truth is that these are the kind of issues that the Garda investigation into the murder must – and will – attempt to establish. Broadcasting a purported version of events widely on social media puts individuals at risk; but it might also make it more difficult for the State and the Gardaí to secure a conviction, if the case is made that the trial has been contaminated.

There is a guilty man. We know that. This may be him. From the evidence that has been reported that seems likely. But we do not know anything about his personal history. Nor do we know how his brother or, for that matter, other members of his family responded.

It is utterly wrong, therefore, for anyone to claim knowledge of any of these matters that are properly part of a full and above all carefully constructed and managed investigation. A second man has been arrested. Perhaps more than one person will be charged. Perhaps that is the correct outcome. But in the meantime, the members of the family of any suspect have the right to their own personal integrity, and to the presumption of their individual innocence.

The Romanian man who was first targeted on social media might himself have been attacked or murdered. And if you think that’s an exaggeration, watch the RTÉ programme about the shocking miscarriage of justice which followed the abduction and murder of Una Lynskey 50 years ago, in 1972. Not only were two innocent men sent to jail in a disgraceful rush to judgement, but Martin Kerrigan, the third of the three young men framed by Gardaí at the time, was abducted and murdered.

The irrational emotions that led to the murder of Martin Kerrigan are unleashed far more easily, and potentially given a far more dangerous momentum now, by the way in which mob instincts are supercharged on social media.

To complicate the dangers, there are people who have a vested interest in stirring up animosity and hatred. Who will operate under false flags. Who will cynically exploit any tragedy to their own base ends.

And so it was declared and widely shared on social media that the perpetrator was an asylum seeker. That he was living in direct provision. These were deliberate lies, knowingly put into the public domain. Clearly the relatively small number of seriously committed racists in Ireland are already trying to exploit the fact that the prime suspect is not Irish, using it as an opportunity to attack the presence of so called ‘foreign nationals’ in Ireland. They must not be allowed to do this; or indeed to get away with it if they do.

Far more crimes of violence are carried out in Ireland by Irish people than by anyone who might be described as an immigrant.

With that in mind, we really do need to introduce the promised bill on Hate Speech. And, as part of that bill, we must make social media companies responsible for the hate speech that occurs so regularly and without screening on their platforms. The last thing we need, or I am sure that she would want, is for the murder of Ashling Murphy to be used to fan the sick flame of racism in Ireland.

Ashling Murphy vigil at the Leinster House, Dublin. Friday 14th of January 2022. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Ashling Murphy vigil at the Leinster House, Dublin. Friday 14th of January 2022. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.VIOLENCE BEGETS VIOLENCE

Full circle. We really do need to think long and hard about the way in which anger is accepted and even encouraged in people, without any apparent sense of the perils it creates or can open up.

We must start this process by acknowledging that there are men all over the world whose attitude to women is twisted crazily out of shape. Who harbour a sense of grievance that they cannot form relationships. Who think that the world – and women in particular – owe them a life in which their sexual urges can and will be satisfied. They too are given a platform on social media to foment their hatred and resentment of women.

There are other men who are bullies plain and simple. Who never succeeded in moving beyond the adolescent stage of demanding what they want and striking out if the world – or more often the unfortunate woman who is unlucky enough to be living with them – doesn’t provide it.

And then there are others who have a capacity for anger in them that can be provoked by the most minor frustration. These are the kind of individuals that get involved in road rage incidents. Who shout and roar if, as one murder suspect put it, ‘the grub’ isn’t on the table when they arrive home in the evening. Or who are so angry at everyone and everything that they strike out aggressively against society in general by attacking or hurting individuals.

I have heard it argued that anger is a good and necessary thing. Or as Johnny Lydon put it “Anger is an energy.” I have always assessed it differently.

I have seen things said and done in anger that have had terrible, unintended and sometimes life-changing repercussions for the individuals responsible. And so I simply refuse to allow it in. The resolve is that anger should have no place in anything I do or say.

The inescapable truth is that anger is extremely dangerous. A huge amount of the violence and aggression that afflicts so many individuals and families is a direct result of anger. Far from encouraging it, we all need to learn how to defuse it in ourselves, and in other people too.

Men in particular need to learn anger management. We need to control our negative emotions. We need to learn to walk away rather than start a fracas. We need to go beyond any lurking sense of resentment. We need to be committed to behaving like balanced, sensible, rational human beings. And to realise that violence begets violence. That it is the road to nowhere good. And that too often it leads to a living hell on earth for the people who are in its orbit. Or your orbit if you are the one who is striking out.

I know, I know: sometimes words really are inadequate. That resolution wouldn’t have saved Ashling Murphy, who was attacked out of the blue for no reason whatsoever under the sun. But we can aim to do it in her honour nonetheless: to suppress and finally kill off the anger gene that hurts so many.

The President put it eloquently: “Let us respond to this moment of Ashling’s death by committing to the creation of a kinder, more compassionate and empathetic society for all, one that will seek to eliminate all threats of violence against any of our citizens, and commit in particular to bringing an end, at home and abroad, to violence against women in any of its forms.”

If we could do just that, the world – or the part of it that we inhabit at least – would be a far better place.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 17 Oct 23

Prosecution to outline case in Ashling Murphy murder trial

- Opinion

- 27 Jan 22

Man Disrupts People Before Profit Meeting on Gender-based Violence

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 27 Jan 22

The Whole Hog: The 10 Big Issues We’ll Wrestle With In 2022

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 14 Jan 22