- Culture

- 14 Jun 20

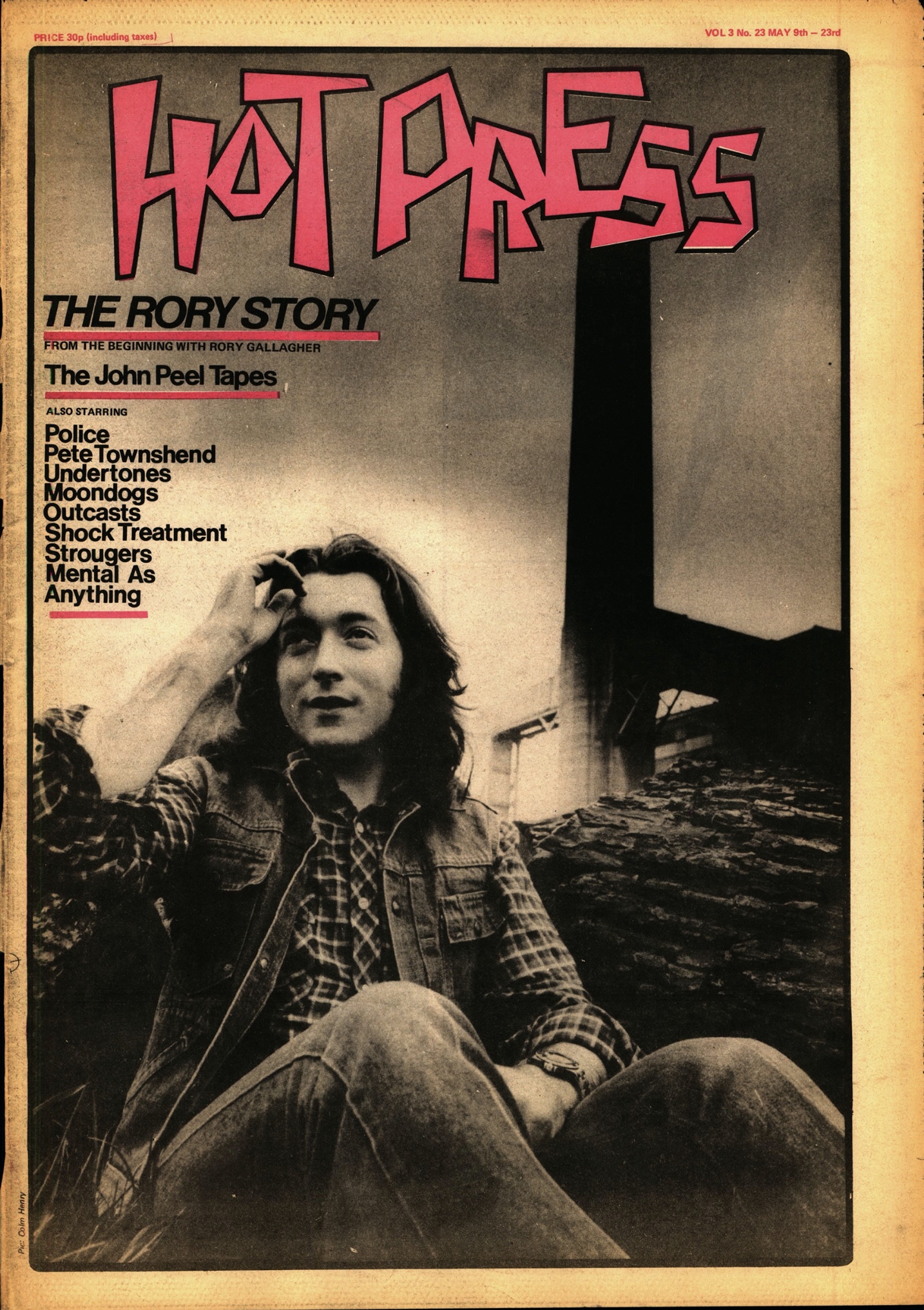

There is a huge volume of extraordinary material in the Hot Press vaults – not least about the great guitar maestro, whose anniversary we are remembering today. Of course, there was a lot of fun to be had, but one of the serious things that we set out to do in Hot Press was to create a kind of living history of Irish music. We wanted to hear the back story. To provide a context. And generally to help make the wider public aware of just how powerful a force rock 'n' roll really was at the time, and can be. That has been proven a hundred thousand times since – but what happened later was only possible because of the pioneering work of players like Rory. This interview, conducted by Dermot Stokes in 1980, offers a marvellous window into the life of a genius guitar player, band leader and songwriter, finding his way in the world – and delivering extraordinary, enduring music that is still loved and remembered today...

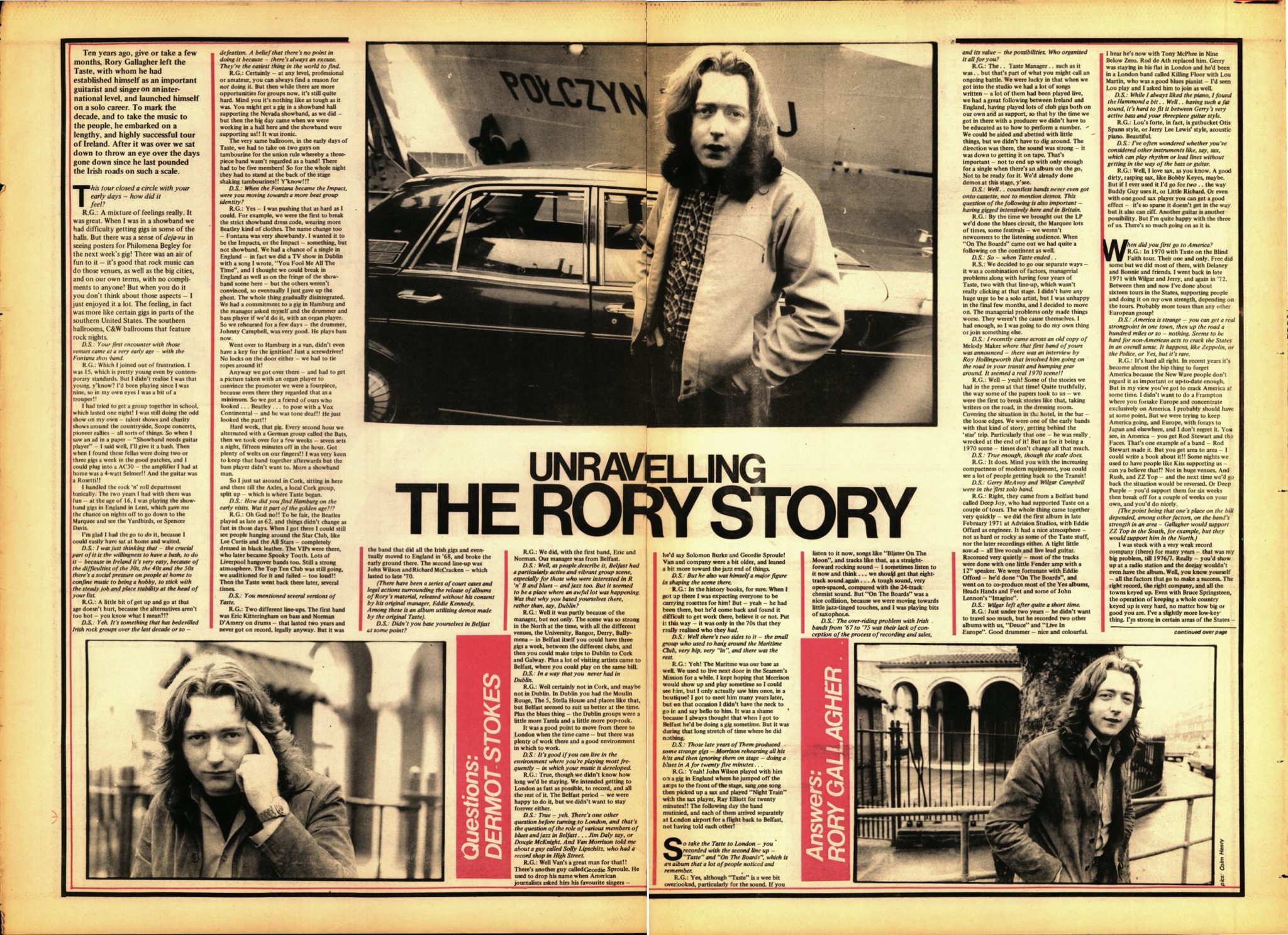

Ten years ago, give or take a few months, Rory Gallagher left Taste, with whom he had established himself as an important guitarist and singer on an international level. Rory launched himself on a solo career.

To mark the end of a decade working solo, and to take the music to the people, he embarked on a lengthy, and highly successful tour of Ireland. After it was over, we sat down to throw an eye over the days that have gone down since he last pounded the Irish roads on such a scale.

Dermot Stokes: This tour closed a circle with your early days — how did it feel?

Rory Gallagher: A mixture of feelings really. It was great. When I was in a showband, we had difficulty getting gigs in some of the halls. But there was a sense of deja-vu in seeing posters for Philomena Begley for the next week’s gig! There was an air of fun to it — it’s good that rock music can do those venues, as well as the big cities, and on our own terms, with no compliments to anyone! But when you do it, you don’t think about those aspects — I just enjoyed it a lot. The feeling, in fact, was more like certain gigs in parts of the southern United States. The southern ballrooms, C&W ballrooms that feature rock nights.

Your first encounter with those venues came at a very early age — with the Fontana showband.

Which I joined out of frustration. I was 15, which is pretty young even by contemporary standards. But I didn’t realise I was that young, y’know? I’d been playing since I was nine, so in my own eyes I was a bit of a trouper!!

I had tried to get a group together in school, which lasted one night! I was still doing the odd show on my own — talent shows and charity shows around the countryside, Scope concerts, pioneer rallies — all sorts of things. So when I saw an ad in a paper — “Showband needs guitar player” — I said well, I’ll give it a bash. Then, when I found these fellas were doing two or three gigs a week in the good patches, and I could plug into a AC30 — the amplifier I had at home was a 4-watt Selmer!! And the guitar was a Rosetti! I handled the rock ‘n’ roll department basically. The two years I had with them was fun — at the age of 16, I was playing the showband gigs in England in Lent, which gave me the chance, on nights off, to go down to the Marquee (in London) and see The Yardbirds, or Spencer Davis. I’m glad I had the go to do it, because I could easily have sat at home and waited.

Advertisement

I was just thinking that — the crucial part of it is the willingness to have a bash, to do it — because in Ireland it’s very easy, because of the difficulties of the 30s, the 40s and the 50s there’s a social pressure on people at home to confine music to being a hobby, to stick with the steady job and place stability at the head of your list.

A little bit of get up and go at that age doesn’t hurt, because the alternatives aren’t too hot — you know what I mean?!?

Yeh. It’s something that has bedevilled Irish rock groups over the last decade or so — defeatism. A belief that there’s no point in doing it because — there’s always an excuse. They’re the easiest thing in the world to find.

At any level, professional or amateur, you can always find a reason for not doing it. But then, while there are more opportunities for groups now, it’s still quite hard. Mind you it’s nothing like as tough as it was. You might get a gig in a showband hall supporting the Nevada Showband, as we did — but then the big day came when we were working in a hall here and the showband were supporting us!! It was ironic. The very same ballroom, in the early days of Taste, we had to take on two guys on tambourine for the union rule whereby a three-piece band wasn’t regarded as a band! There had to be five members! So for the whole night they had to stand at the back of the stage shaking tambourines!! Y’know!!?

When the Fontana became the Impact, were you moving towards a more beat group identity?

Yes — I was pushing that as hard as I could. For example, we were the first to break the strict showband dress code, wearing more Beatle-y kind of clothes. The name change too — Fontana was very showband-y. I wanted it to be the Impacts, or the Impact — something, but not showband. We had a chance of a single in England — in fact we did a TV show in Dublin with a song I wrote, 'You Fool Me All The Time', and I thought we could break in England as well as on the fringe of the showband scene here — but the others weren’t convinced, so eventually I just gave up the ghost. The whole thing gradually disintegrated. We had a commitment to a gig in Hamburg and the manager asked myself and the drummer and bass player if we’d do it, with an organ player. So we rehearsed for a few days — the drummer, Johnny Campbell, was very good. He plays bass now. Went over to Hamburg in a van, didn’t even have a key for the ignition! Just a screwdriver! No locks on the door either — we had to tie ropes around it!

Sounds very sophisticated!

Anyway we got over there — and had to get a picture taken with an organ player to convince the promoter we were a four-piece, because even there, they regarded that as a minimum. So we got a friend of ours who looked ... Beatle-y ... to pose with a Vox Continental. He was tone deaf!! He just looked the part!! Hard work, that gig. Every second hour we alternated with a German group called The Bats, then we took over for a few weeks — seven sets a night, fifteen minutes off in the hour. Got plenty of welts on our fingers!! I was very keen to keep that band together afterwards but the bass player didn’t want to. More a showband man. So I just sat around in Cork, sitting in here and there till The Axles, a local Cork group, split up — which is where Taste began.

How did you find Hamburg on the early visits. Was it part of the golden age?

Oh God no!! To be fair, The Beatles played as late as '62, and things didn’t change as fast in those days. When I got there, I could still see people hanging around the Star Club, like Lee Curtis and the All Stars — completely dressed in black leather. The VIPs were there, a band who later became Spooky Tooth. Lots of Liverpool hangover bands too. Still a strong atmosphere. The Top Ten Club was still going, we auditioned for it and failed — too loud!! Then the Taste went back there later, several times.

You mentioned several versions of Taste.

Two different line-ups. The first band was Eric Kitteringham on bass and Norman D’Amery on drums — that lasted two years and never got on record, legally anyway. But it was the band that did all the Irish gigs and eventually moved to England in ‘68, and broke the early ground there. The second line-up was John Wilson and Richard McCracken — which lasted to late ‘70.

Didn’t you base yourselves in Belfast at some point?

We did, with the first band, Eric and Norman. Our manager was from Belfast.

Advertisement

(There have been a series of court cases and legal actions surrounding the release of albums of Rory’s material, released without his consent by his original manager, Eddie Kennedy. Among these is an album utilising demos made by the original Taste).

Well, as people describe it, Belfast had a particularly active and vibrant group scene, especially for those who were interested in R ‘n’ B and blues — and jazz too. But it seemed to be a place where an awful lot was happening. Was that why you based yourselves there, rather than, say, Dublin?

Well it was partly because of the manager, but not only. The scene was so strong in the North at the time, with all the different venues, the University, Bangor, Derry, Ballymena — in Belfast itself, you could have three gigs a week, between the different clubs, and then you could make trips to Dublin to Cork and Galway. Plus a lot of visiting artists came to Belfast, where you could play on the same bill.

In a way that you never had in Dublin.

Well certainly not in Cork, and maybe not in Dublin. In Dublin, you had the Moulin Rouge, The 5, Stella House and places like that, but Belfast seemed to suit us better at the time. Plus the blues thing — the Dublin groups were a little more Tamla and a little more pop-rock. It was a good point to move from there to London when the time came — but there was plenty of work there and a good environment in which to work.

It’s good if you can live in the environment where you’re playing most frequently — in which your music is developed.

True, though we didn’t know how long we’d be staying. We intended getting to London as fast as possible, to record, and all the rest of it. The Belfast period — we were happy to do it, but we didn’t want to stay forever either.

True — yeh. There’s one other question before turning to London, and that’s the question of the role of various members of blues and jazz in Belfast – Jim Daly say, or Dougie McKnight. And Van Morrison told me about a guy called Solly Lipschitz, who had a record shop in High Street.

Well Van’s a great man for that!! There’s another guy called Geordie Sproule. Van used to drop his name when American journalists asked him his favourite singers — he’d say Solomon Burke and Geordie Sproule! Van and company were a bit older (than Taste), and leaned a bit more toward the jazz end of things.

But he also was himself a major figure in shaping the scene there.

In the history books, for sure. When I got up there, I was expecting everyone to be carrying rosettes for him! But - yeah - he had been there, but he’d come back and found it difficult to get work there, believe it or not. Put it this way - it was only in the 70s that they really realised who they had.

Well there’s two sides to it - the small group who used to hang around the Maritime Club, very hip, very “in and then there was 'the rest'.

Yeh! The Maritime was our base as well. We used to live next door in the Seamen’s Mission for a while. I kept hoping that Morrison would show up and play sometime so I could see him, but I only actually saw him once, in a boutique! I got to meet him many years later, but on that occasion I didn’t have the neck to go in and say hello to him. It was a shame, because I always thought that when I got to Belfast he’d be doing a gig sometime. But it was during that long stretch of time where he did nothing.

Advertisement

Those late years of Them produced some strange gigs - Morrison rehearsing all his hits and then ignoring them on stage - doing a blues in A for twenty five minutes...

Yeah! John Wilson played with him on a gig in England where he jumped off the amps to the front of the stage, sang one song then picked up a sax and played 'Night Train' with the sax player, Ray Elliott for twenty minutes! The following day the band mutinied, and each of them arrived separately at London airport for a flight back to Belfast, not having told each other!

So take the Taste to London - with the second line up you recorded Taste and On The Boards – which is an album that a lot of people noticed and remember.

Yes, although Taste is a wee bit overlooked, particularly for the sound. If you listen to it now, songs like 'Blister On The Moon', and tracks like that, as a straightforward rocking sound - I sometimes listen to it now and think: we should get that eight-track sound again. A tough sound, very open-spaced, compared with the 24-track chemist sound. But On The Boards was a nice collision, because we were moving towards little jazz-tinged touches, and I was playing bits of saxophone.

The over-riding problem with Irish bands from ‘67 to ‘75 was their lack of conception of the process of recording and sales, and its value - the possibilities. Who organised it all for you?

The Taste manager, such as it was – but that’s part of what you might call an ongoing battle. We were lucky in that when we got into the studio we had a lot of songs written – a lot of them had been played live, we had a great following between Ireland and England, having played lots of club gigs both on our own and as support, so that by the time we got in there with a producer we didn’t have to be educated as to how to perform a number. We could be aided and abetted with little things, but we didn’t have to dig around. The direction was there, the sound was strong - it was down to getting it on tape. That’s important - not to end up with only enough for a single when there’s an album on the go. Not to be ready for it. We’d already done demos at this stage, y’see.

Well, countless bands never even got onto cassette, not to mention demos. This question of the following is also important - having gigged intensively here and in Britain.

By the time we brought out the LP we’d done the blues circuit, the Marquee lots of times, some festivals - we weren’t newcomers to the listening audience. When On The Boards came out we had quite a following on the continent as well.

So - when Taste ended...

We decided to go our separate ways - it was a combination of factors, managerial problems along with having four years of Taste, two with that line-up, which wasn’t really clicking at that stage. I didn’t have any huge urge to be a solo artist, but I was unhappy in the final few months, and I decided to move on. The managerial problems only made things worse. They weren’t the cause themselves. I had enough, so I was going to do my own thing or join something else.

I recently came across an old copy of Melody Maker where that first band of yours was announced - there was an interview by Roy Hollingworth that involved him going on the road in your transit and humping gear around. It seemed a real 1970 scene!

Well - yeah! Some of the stories we had in the press at that time! Quite truthfully, the way some of the papers took to us - we were the first to break stories like that, taking writers on the road, in the dressing room. Covering the situation in the hotel, in the bar - the loose edges. We were one of the early bands with that kind of story, getting behind the ‘star’ trip. Particularly that one - he was really wrecked at the end of it! But as for it being a 1970 scene - times don’t change all that much.

True enough, though the scale does.

It does. Mind you with the increasing compactness of modern equipment, you could see a lot of people getting back to the Transit!

Advertisement

Gerry McAvoy and Wilgar Campbell were in the first solo band.

Right, they came from a Belfast band called Deep Joy, who had supported Taste on a couple of tours. The whole thing came together very quickly: we did the first album in late February 1971 at Advision Studios, with Eddie Offard as engineer. It had a nice atmosphere - not as hard or rocky as some of the Taste stuff, nor the later recordings either. A tight little sound - all live vocals and live lead guitar. Recorded very quietly - most of the tracks were done with one little Fender amp with a 12” speaker. We were fortunate with Eddie Offord - he’d done On The Boards, and went on to co-produce most of the Yes albums, Heads Hands and Feet and some of John Lennon’s Imagine.

Wilgar left after quite a short time.

Just under two years - he didn’t want to travel so much, but he recorded two other albums with us, Deuce and Live In Europe. Good drummer - nice and colourful. I hear he’s now with Tony McPhee in Nine Below Zero. Rod deAth replaced him. Gerry was staying in his flat in London and he’d been in a London band called Killing Floor with Lou Martin, who was a good blues pianist - I’d seen Lou play and I asked him to join as well.

While I always liked the piano, I found the Hammond a bit – having such a fat sound, it’s hard to fit it between Gerry’s very active bass and your three-piece guitar style.

Lou’s forte, in fact, is gutbucket Otis Spann style, or Jerry Lee Lewis’ style, acoustic piano. Beautiful.

I’ve often wondered whether you’ve considered other instruments like, say, sax, which can play rhythm or lead lines without getting in the way of the bass or guitar.

Well, I love sax, as you know. A good dirty, rasping sax, like Bobby Keyes, maybe. But if I ever used it I’d go for two – the way Buddy Guy uses it, or Little Richard. Or even with one good sax player you can get a good effect - it’s so sparse it doesn’t get in the way but it also can riff. Another guitar is another possibility. But I’m quite happy with the three of us. There’s so much going on as it is.

When did you first go to America?

In 1970 with Taste on the Blind Faith tour. Their one and only. Free did some, but we did most of them, with Delaney and Bonnie and friends. I went back in late 1971 with Wilgar and Gerry, and again in ‘72. Between then and now I’ve done about sixteen tours in the States, supporting people and doing it on my own strength, depending on the tours. Probably more tours than any other European group!

America is strange - you can get a real strongpoint in one town, then up the road a hundred miles or so - nothing. Seems to be hard for non-American acts to crack the States in an overall sense. It happens, like Zeppelin, or The Police, or Yes, but it’s rare.

It’s hard all right. In recent years it’s become almost the hip thing to forget America because the New Wave people don’t regard it as important or up-to-date enough. But in my view you’ve got to crack America at some time. I didn’t want to do a Frampton where you forsake Europe and concentrate exclusively on America. I probably should have at some point. But we were trying to keep America going, and Europe, with forays to Japan and elsewhere, and I don’t regret it. You see, in America - you get Rod Stewart and the Faces. That’s one example of a band - Rod Stewart made it. But you get area to area - I could write a book about it!! Some nights we used to have people like Kiss supporting us - can ya believe that!? Not in huge venues. And Rush, and ZZ Top - and the next time we’d go back the situation would be reversed. Or Deep Purple - you’d support them for six weeks then break off for a couple of weeks on your own, and you’d do nicely. (The point being that one’s place on the bill depended, among other factors, on the band’s strength in an area - Gallagher would support ZZ Top in the South, for example, but they would support him in the North.)

I was stuck with a very weak record company (there) for many years - that was my big problem, till 1976/7. Really - you’d show up at a radio station and the deejay wouldn’t even have the album. Well, you know yourself - all the factors that go to make a success. The right record, the right company, and all the towns keyed up. Even with Bruce Springsteen, the operation of keeping a whole country keyed up is very hard, no matter how big or good you are. I’ve a slightly more low-key thing. I’m strong in certain areas of the States - we always get a good reception, I can play there and learn from it, they can enjoy what I do, or not. I’m not trying to be Frampton, or Springsteen. Eventually it might crack 'nationwide' on an album. But... I just like to play there and enjoy it.

An awful lot of what happens in America seems very sort of — hit and miss. Very accidental. There is no particular logic, nor is there any particular justice.

The only justice you get is Bob Seger — who worked his backside off all over the country and became a regional hit in Detroit and worked out of there. Then you get someone like Andrew Gold who worked with Linda Ronstadt, he had a big gold album and a hit single — and he might do a gig 200 miles from Los Angeles and have only a handful of people turn up. You know what I mean? Couldn’t sell a seat in Houston — just as an example. A hit album doesn’t mean you’re drawing people in gigs, and vice versa in my case! (laughs). You can’t be Yogi Bear and Cyrus Vance! You can’t be everybody. You just spread the music. Anyway I’m confident I’ll crack it whatever way I’m supposed to crack it. And as long as I’m playing to my people out there, it’s all you can ask for.

Advertisement

Have you encountered many of the old bluesmen in America? Like, as a bonus of playing there have you caught up on any of the legends?

Yeah! For the likes of me it’s a holiday, because I was on the same bill as Freddie King, and John Hammond. On nights off I’ve seen, let’s see, Albert King, Muddy Waters, Juke Boy Bonner — we shared a bill down in Texas. He’s dead now. Albert Collins, Fred McDowell — I saw him in New York before he died. But I’ve seen more of the old acoustic blues fellas at the Folk-Blues Festival in London! I saw Hound Dog Taylor in Chicago in a black club. He called us up to play on stage. I played his guitar. He had it tuned to E minor! A Japanese Star guitar!! Out of Woolworths — the neck was like on a saw, it was so bent! But it was... an experience!

Since we’re talking about these fellows: you recorded with a number of seminal influences, didn’t you?

Muddy Waters, Albert King and Jerry Lee Lewis were the ones, and a Lonnie Donegan album later. I did most of the Muddy tracks in London, and in fact a second album came out with the out-takes. The Albert King one was live at Montreux, where I was asked to sit in, without rehearsal. It was alright. But the Muddy Waters one was more enjoyable. We did it in three nights in London with Mitch Mitchell, Georgie Fame, all those fellas. But I was doing gigs at the same time, so they had to hold the sessions till I’d fly back from Birmingham or somewhere!! With my Vox and the Strat in the back! It was great because I hit it off well with Muddy on the first night, and they were supposed to start at ten or so, but they’d hold it up; and he’d be sitting there holding a paper cup with a drink in it when I’d come in the door panting! Good for the morale! But I learned from Muddy just tuning his guitar, sitting there with his cigar in his mouth — the whole calm vibe off him. But he could really switch on the menace when he played. Great for a man — he was in his late 50s then. The controlled power! Jerry Lee was a madder thing. That was all in one afternoon, and... Well, Muddy didn’t rehearse, but he’d know the key, and he’d run through the riff, but Jerry Lee would just shout out the key and start! 'Whole Lotta Shakin’ on the album — just... started!! Literally from the key. In the studio he’s worse then he is on stage. Lifting up the piano and all the rest. Bottle of Bourbon in a brown paper bag next to him at the piano. He’s no fake! Good session! Good laugh!

On another area altogether, you’ve gathered a team working for you that seem particularly in tune with your personality and music. The legendary Tom O’Driscoll is one. Tom actually had a baptism of fire, I hear. The crowd invaded the stage and when he cleared them off he realised he couldn’t see you.

That’s right!! He threw me off the stage!! In Nottingham, I think. I’d known him for years, he’d helped out now and then. But on his first gig as a member of the crew, not having seen us for a while, Donal told him 'Listen the crowd might get a little jumpy and get on the stage — so if they do, gently move them off the stage. Don’t get rough’. Anyway a group got on stage, and Tom sort of panicked and grabbed a bunch of people and pushed them off the stage, including me, y’know?!? So there I am trying to climb back on stage with a guitar lead in my hand! So he ran away and hid!

Tom seems to me to be a round peg in a round hole — perfect for the situation he’s in.

The first time I met Tom was down in Schull Town Hall. The showband was playing there, and the rhythm section used to do a thing on our own before the crowd came in, for our own fun — Rock ‘n’ Roll stuff — and a bunch of the local Schull teds happened to be there, including Tom with the bebop hairdo and the white drape jacket. And we finished a few numbers and he rambled up to the side of the stage and I thought — here we go! Trouble! So he said, ‘Yeah, could you do that Buddy Holly song again!’

Aside from getting tossed off stage by your roadies, you’ve done a bit of knocking over yourself. Like I’ve seen mikes scattered all over the stage!!

Sometimes, on a good night I don’t mind going a bit ape!!

Have you ever considered the radio antennae that don’t need any leads?

I’m not crazy about them. I’d hate to get that self-conscious about being active onstage. Though Pat Travers uses them, and Lizzy. Heart do too.

Dire Straits use them too.

Do they?! (Pause). But they don’t need them — they don’t move!! (laughs).

Advertisement

You got into a lot of changes after the Irish Tour album. Calling Card was gentler, after Against The Grain, while Photo-Finish was back to the three-piece sound. That, and Top Priority being a break with Calling Card.

I was keener on the sound in Against The Grain than in the rock numbers on Calling Card, which had a mood alright — but maybe we were too varied in the material. Going from 'Secret Agent' to 'I’ll Admit You’re Gone'. But it was probably the best from the keyboards point of view. But all that aside, I think that Photo-Finish, because of the change of line-up, and because of a certain change in my own space and time, and everything else, with Top Priority, makes quite a break from all the other albums — a rebirth, in terms of songwriting, in knowing what I want. Lots of changes went down. Lots of things. I was back in the driver’s seat again, because I’d laid back long enough on Calling Card to let somebody else produce it. Partly it’s just practice in knowing what works. But also I didn’t fight the studio anymore, I used it. I was less obsessed with putting down live vocals, or lead guitar — if a song needed overdubs for texture, it got them. However, that said, we did the last two on 24-track, but we’ll do the next studio album of 16. And I wouldn’t even object to moving towards 8, because I think the sound quality of 16 is better than 24.

Well, have you specific ideas now — I’ve heard talk of a live album.

Yes, that’s almost definite now. Almost. I’m listening to tapes now. We recorded all but two of the Irish gigs, and the Lyceum in London, some in France, San Francisco, EA, Cleveland. So I’ve gone through all of those. I’d like the next album to be live, because the particular mood the band is in, the performances and so on, are right — unless something goes wrong, not enough stuff, or whatever. Then follow that with a studio album reasonably quickly. As for that, I’ve a few ideas all right — more a framework than a body of material at the moment. Material — that’s what it comes down to in the end, though... and survival!!

...One need hardly say more, except that if the savage energy of the recent gigs can be adequately captured on vinyl, then it’ll make the most riveting recording of the year. Meanwhile Gallagher, while perfectly willing to discuss the last decade, is more concerned with the next.

What it will bring is anybody’s guess — perhaps even the major American breakthrough? One way or the other he’ll be there, giving his best. I, for one, couldn’t ask for more.

• This article originally appeared in Hot Press Vol.3 No.23, under the headline Unravelling The Rory Story. Hot Press 44-07 is a special tribute to Rory Gallagher on the 25th Anniversary of his passing.