- Culture

- 28 Dec 20

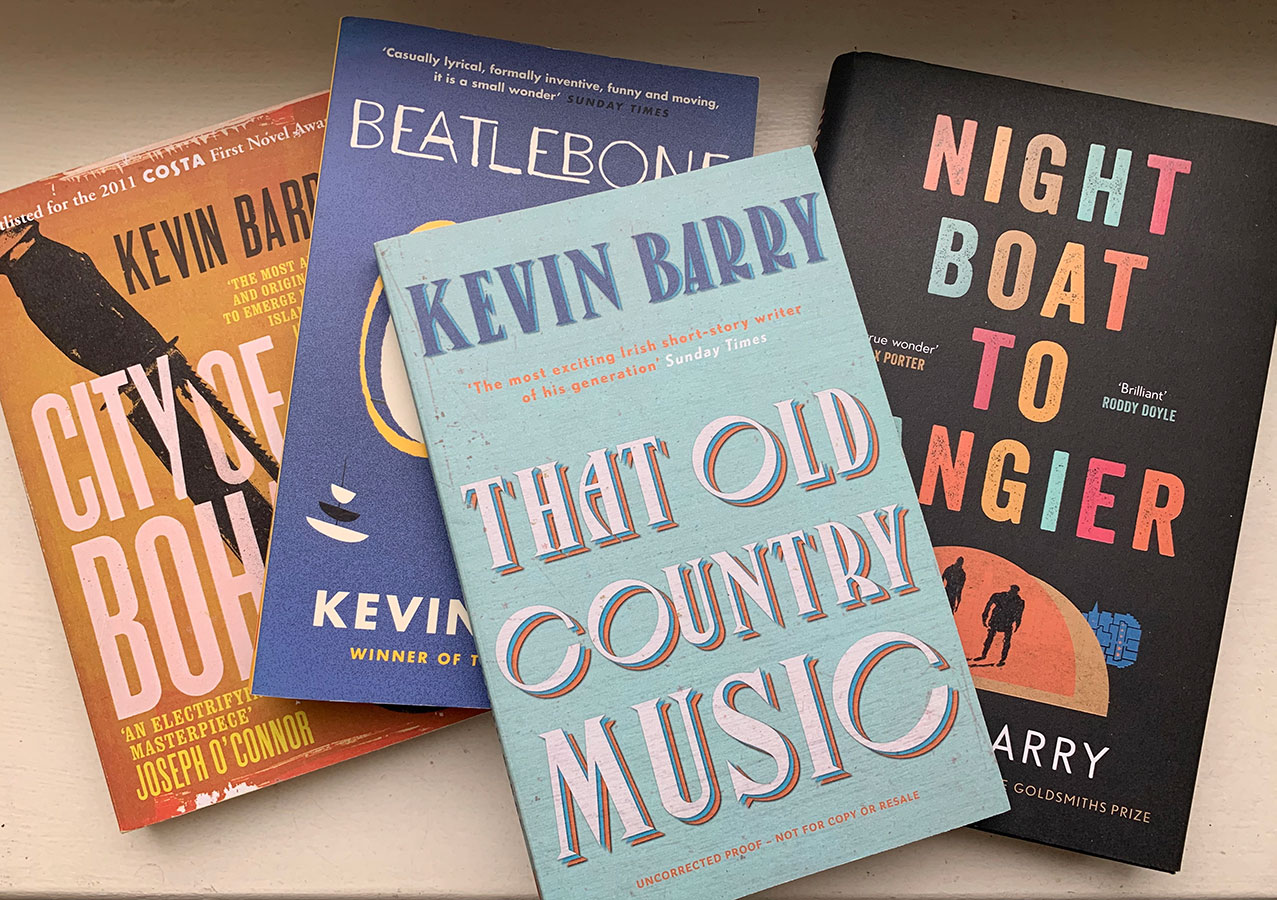

As part of the The 12 Interviews of Xmas, we're looking back at some of our classic interviews of 2020. With his brilliant new short story collection, That Old Country Music, Kevin Barry has proven yet again that he is one of our most gifted writers, effortlessly evoking the west of Ireland that he has placed himself in. “When I cross the Shannon,” he told Pat Carty in November, “I honestly feel my breath happily deflating.” Portraits: Louise Manifold.

First things first, Mr Kevin Barry, one of our finest novelists and easily our finest short story writer, was recently elected to Aosdána, Charlie Haughey’s laudable artistic quango. I don’t want to risk any sort of cultural faux pas, so I need to know how to address him.

“I'm not a stickler for the etiquette at all,” says Barry, down the phone from the wilds of Sligo. “You can just say ‘Your Excellency’ or ‘Your Grace’.”

Such airy artistic standing surely allows him to graze his sheep on all lands west of the Shannon, or at least claim droit de seigneur?

“To be quite honest, I don’t know a huge amount about it other than it's the kind of Irish Academy thing,” he admits, somewhat disappointingly. “And that it’s limited to 250 so people need to pass away before new people can be elected. It was a nice surprise to get the call last week.”

This isn’t the first award that Barry has been on the receiving end of. He won the International Dublin Literary Award for his debut novel City Of Bohane in 2013, and 2019’s Night Boat To Tangier was long-listed for the Booker Prize, as well as being named one of the year’s top books by the New York Times. Everybody likes a pat on the back, and the Dublin Literary Award carries a substantial cash prize, but what do accolades like this really mean to a writer?

Advertisement

“Pragmatically, if there's money involved, it buys you time,” Barry reasons. “In terms of a glow of satisfaction, there's nothing not to love about winning prizes. It's amazing how quickly the buzz of winning a prize can pass you by in a way - It doesn't necessarily get you through the wet November Tuesdays - but there's luck involved to win anything.”

People may well have an illusory idea about how hard it is for a writer to make a living.

“To get by as a writer, if you're concentrating on fiction, you have to be canny, you have to have a lot of irons in the fire. I wouldn't be able to make a living writing short stories, God bless me, or novels, so I do scripts and plays as well. And it also raises a very important question, where are you going to live? Traditionally, a writer would go to a big city, London or Paris or New York or Dublin, and live in a garret and get by. Unless you're from an advantaged background, that's not possible for most emerging writers and artists now. My wife Olivia and I have lived in South County Sligo for 13 years. The decision was made because it was an affordable mortgage, and because if I lived in Dublin, I'd have to be teaching, as well as writing.”

His dander is up, so off he goes.

“I've noticed with a lot of younger and emerging writers, that they're inclined to stay to the smaller places where you don't have to work a lot of jobs. When I was growing up in Limerick in the 80s and 90s - and knocking around with that messer Stuart Clark - if you had any kind of artistic inclinations, there was one thing on your mind, which was to get out of town. You'd move to Dublin or even Cork, which was like Las Vegas! It's more affordable to live in Limerick and there's kind of a scene around now that wasn't really there then, much more of a creative community. The whole hip hop thing has been fantastic for Limerick, It's given the city a confidence that really wasn't there. We used to be very fucking down on ourselves.”

I know Limerick people who could do that for a living.

“Oh God, yeah,” he agrees. “We're an awful crowd. When I moved to Cork in the early 90s, I was stunned because they all love the place. I didn't realise this was possible as an Irish person, that you could like the place you grew up in.”

Advertisement

The Techno Scene

Many people fear that a city centre that prices out its artists is in danger of losing its soul.

“I think it's bad news for a town if artists and writers can't afford to live in it. What it encourages, actually, is very mainstream art.”

Safe Art?

“Safe art. People who can afford big cities are people who make stuff that has great commercial and popular appeal. It might be fantastic work, but that's all that can thrive where a culture is this kind of extravagant and expensive thing. I was reading how the Berlin local government has given thirty gay nightclubs 80 grand each just to keep going during the pandemic. They know that part of Berlin’s signature as a city is its club and techno culture, and they're investing in that whereas can you imagine going into fuckin' Leinster House and saying ‘lads, you're not considering the impact of this on the techno scene!’”

“We're not great at a lot of things in Ireland, but we're pretty good at the creative stuff, arts and writing and music. And we should really be absolutely horsing money into that, If the cheap money is now available. If they're going printing money to get the world out of this, they should try to use it in imaginative ways and support the creative people.”

What about the recent budget, which included a new €50m support for live entertainment, and a record €130m for the Arts Council?

Advertisement

“Obviously, it's great to see it, if it helps places that probably would have shut their doors to keep going,” says Barry. “I don't think the arts community should be too grateful though, it’s a more realistic level for what it brings back into the country.”

Barry is over in Sligo, gazing out at the fields. Is a lockdown the natural habitat for a writer anyway?

“When the first one happened, people were on the radio saying "oh, my life is hell, I'm at home the whole time, and I've to work from the shed’, and I thought, 'welcome to my world',” he laughs. “Our social life is really going around doing literary events and festivals. That's great, and I do miss that very much. But is the day-to-day very different, really? It's probably a very different experience in the country than it is in town. I was down in Dublin for two days about a month ago, recording an audiobook, and that felt very dramatic because I hadn't been there in six months. I felt, ‘fuck, this is seriously eerie!’ When the town empties out after seven or eight o'clock, it feels ghostly. It's a far more dramatic experience than it is down in a field in south county Sligo.”

Cosmic Forces

We should probably discuss his work. As a jack of all literary trades – and a master of some – how does Barry decide what constitutes a short story and what requires the space of a novel?

“There is very often massive confusion and panic over what something is when I have an idea, is it a story or can I make a little play out of it?” he explains. “I tend to try a lot of stuff as a short story first and see if I can get the characters right. I think Maurice and Charlie in Night Boat to Tangier originally showed up in a short story before being tried out in a play, and then eventually realising ‘oh fuck it, I have to give them a longer thing, they won’t shut up’. A lot of my favourite stories were written quite quickly, probably inside a week or two, while others can be dragging on for years. If you're congenitally impatient, the idea of getting a finished thing, whether it's good or bad, onto your desk inside of a week or two is very attractive.”

“I start a lot of stories, but probably only one or two out of ten work out to any degree, really. I do try to finish them all, I have a weird kind of belief that if you finish all the bad ones, you'll earn the odd good one. A reward from the cosmic forces kind of a thing.”

Advertisement

There might be several pots on the boil at any one time.

“There'd often by two or three that I'd open in the morning and gain nothing and then open another one and hopefully that'll move forward a little bit,” is how he describes it. “You find out one is going well if you're looking forward to going to the desk in the morning, although that's rare enough. It’s a very rewarding thing really, it feels like a bit of a gift from benign forces in the cosmic ether to get one that's working out for you.”

Do you get ones that roll along and write themselves?

“Sometimes the story takes off, and stands on its on two legs, and surprises you in the way its tone changes. That's what you're hoping for. You can't force it and there's a lot of sitting through the worst stories and the average stories before you hit on the good ones. I hate all those old cliches about writing but a lot of them have truth in them, it is 95% perspiration, there's no shortcut through that dreary slog of writing draft after draft. But it is a buzz to get one you know is going to work, it fuels you to go back for more punishment.”

Night Boat To Tangier is every bit as good as people say it is, but there was criticism that it was a little dialogue heavy.

“A lot of my work is very heavy on talk,” Barry admits. “I think it was Nabokov, or however you pronounce his name, who said that if he opened a novel or a short story and there was loads of dialogue, he would immediately fling it across the room. It's not for every reader, but Tangier is built out of the single conversation really. Even though it's a very theatrical kind of setup, it very quickly became apparent as I was writing it that it needed to be a novel because the story kept going back into their past. And that's the great thing about a novel, you can go in any kind of direction time-wise. That's much more difficult on a stage or in a film but the novel can go in any direction, it's kind of an unimprovable form in lots of ways. If the sentences and the paragraphs are good enough, the reader will keep turning the pages.”

Advertisement

Into The West

The west of Ireland is as much a character in Barry’s work as any other, it’s there in City Of Bohane, Beatlebone, the flashbacks in Night Boat To Tangier, and most especially in the new collection, That Old Country Music.

“Oh, very much so,” Kevin agrees. “Limerick is weird one, it's absolutely in the west of Ireland, but it never seems to be part of what you'd imagine as ‘the west’. You imagine rocky hills in Connemara and you imagine Galway, maybe, but you don't imagine Limerick. It's the Northwest I'm writing about, that kind of inland bit where Roscommon and Leitrim and Sligo are jostling up against each other, the tri-state zone as I call it. About four or five years after I moved here, the immediate environment was showing up more. We were talking earlier about where a writer is going to base herself or himself. It turns out to be a really important creative decision, because the place is going to start colouring the work in all sorts of ways.”

He’s very obviously in love with where he is.

“When I write a story, it tends to be set close enough to home, and given that I don't get out of the place at all anymore, it'll probably become even more emphasised. If I'm coming back from Dublin through Carrick-on-Shannon and cross the Shannon river, I honestly feel my breath happily deflating back into the West, back in civilisation. One of the weird things about Ireland, and I think one of the reasons why it has a lot of really good writers and musicians and artists is that for a very small place, geographically, its atmosphere changes a lot within quite short distances. The rural interior Northwest where I am is so very different from parts of Mayo, which are 40 miles out the road. It's not just the scenery, the souls are different, the sense of humour is different. Having grown up in Limerick and spent a lot of time in Cork, I wondered did they have any sense of humour here? it's very deadpan, it's very kind of straight face, a midlands man like yourself would be more familiar with it.”

My breath tends to relax when I get out of the midlands, but that’s another story. This talk of a specific kind of sense of humour calls to mind something that Barry shares with Patrick McCabe and even Tommy Tiernan, this incorporation of the country madness that’s familiar to anyone who grew up outside the Pale.

“I'd admire the work of those two gentlemen very much, it's what Pat calls the stray sod country, there's kind of a mystery to it. In some ways, I go on too much about places giving off their own vibrations and tuning in to those, but it feels like there are stories out there waiting for you, almost. One of my many mad mystical believes is that your stories are there somewhere already, finished, and you just have to beat down the path to them.”

Advertisement

Like a musician tuning in the antenna and picking a song out of the air?

“I think all other art forms are just inferior forms of music, really. Everything aspires to the condition of music. Prose fiction is a kind of disappointed musical form. I'm more interested in the rhythm and the sound than anything else about the work, the sentences building up their own kind of rhythm and letting the sound of the sentences almost dictate the story as it comes out. It's a risky enough way to work sometimes, if you're not in tune with yourself. I have often thought that if I were able to sing or play an instrument or play a banjo, I'd be fine, I wouldn't have to write short stories at all.”

Scratching Our Arses

As any of his readers could attest, there is a poetry and a musicality in the prose that Barry turns out.

“It’s dangerous ground,” he cautions. “You can find yourself tiptoeing up against the material becoming too much and too ripe. My own poetry career was cut short when I gave up writing teenage Goth poetry about suicide and girls at about the age of 16.”

While it is of course a great shame that none of this survives, I move away from it by asking if Barry still reads his material aloud to himself as a final litmus test.

“I do I when I feel I'm at a penultimate draft of the story, if it feels like it's nearly ready,” he allows. “I'll print it out and, with the red pen in my hand, I'll read it out and try and pick out the false notes which are far more evident when you hear it on the air than when you're just looking at it. You see where the story is evading itself or isn't really hitting on what it should be, so that's a critical part of it for me still.”

Advertisement

I may be losing the run of myself here, but might this be a throwback to our bardic tradition, where stories were for telling out loud rather than writing down?

“I don't think that's getting highfalutin by any means, it's absolutely true,” Kevin graciously answers. “It sounds almost corny when you talk about Ireland's oral tradition, but we have always been people who sit around fires, scratching our arses, and telling stories. We love the sounds of our own voices, and we repeat ourselves fuckin’ endlessly. We tell the same stories over and over again, but it doesn't matter, all that matters is how well we're telling it. We come from that, and you can blame the weather. For about 10 months a year, it's a phenomenally dreary fucking country. You have to make stuff up or you'd go mad.”

Barry's Gold

Barry's GoldRattlebag

There are no two ways about it, Barry’s latest short story collection, That Old Country Music, is probably the best new book I’ve read all year, but it does start off with a surprise. ‘The County Of Leitrim’ has, of all things, a happy ending.

“I’ve been writing stories in a serious way for a bit more than 20 years and I think it's my first happy ending,” says Barry, sounding almost surprised himself. “This collection is from the last eight years, and that's long enough to see yourself changing a bit as a writer. That story would have been very different If I had written this 10 years ago, I'm sure it would have had a dramatically different ending. It's like I was saying a while ago, sometimes they go off in their own kind of direction, and pull you along. I guess it just felt right to go with that.”

Advertisement

Seamus Ferris seems destined for what Declan Lynch called old fella status before this woman comes along. It all seems to hinge around the line, “there are worse things than embarrassment in the bleak continents of the night”. He takes his chance and ends up being “sucked through the hole in the universe”. Everybody looks back and thinks ‘Jaysus, if I'd I've only talked to yer man, or yer one’ but Seamus goes for it.

“Oh, for sure, yeah. Seamus is all about regret,” Barry agrees. “He’s a very unfortunate thing for an Irish country man to be in that he's very fastidious. He's into French films, and he drinks wine, rather than beer, so he's totally a sore thumb, sticking out of the side of this hill in Leitrim. By whatever fucking miracle he finds this young woman who thinks that this fella's grand. I think for me, the critical line in the story is that it says somewhere that he can handle just about anything except a happy outcome, and that kind of throws a little bit of shade on the ending of the story.”

What about that ending? I don’t want to give the game away, but it’s a bit contrived and more than a bit unlikely.

“Absolutely,” he admits. “It's kind of like, remember the cameras as they say, you have to go with it. It struck me as I was going along that ‘Jesus, I'm writing a love story’, which was kind of a surprise to me. And I just thought ‘fuck it, you have to be unashamed about it and kind of buy into it’. The hardest love story to write is the one where it works out.”

Did you show this to your wife? Did she look at you and say, ‘I just don’t know who you are anymore”?

“Olivia is usually the first reader of the story, and Lucy, who is my agent, reads the stories early on. They'll never tell me something is bad, never outright say 'naw, this is shit' but I know by their eyes, and I'd know by the tone of voice, but it's a story that people have generally responded to well.”

A line in 'Deer Season' has the unnamed young woman entering “a spell of heavy dreaming or quietude such as can open out sometimes in youth if the person is to be an artist.”

Advertisement

“I think again you've hit on the critical line of the story there,” says Barry, making me feel all smug. “It's one of those coming of age artist stories, I suppose she's kind of starting to figure out who she is.”

Because we haven’t mentioned it for a few paragraphs, Barry starts looking out his window on the west again.

“That story is very much dictated by the time of year. I wrote it over two years, each time around late August I went back to it and did a draft. In the summer up here in the northwest it tends to get very humid and swampy, and by August there's a heaviness in the air that can feel almost ominous, and there's something about that atmosphere that got into the story. I noticed, that in almost every story I write, it’s very quickly evident where are we in the year. It does affect the mood of both yourself and the place you're in, and that kind of ominous, late summer kind of dog days feeling up here is something I wanted to bring into a short story.”

Fun House

Uncle Aldo’s cause of death, in 'Old Stock', is listed as the west of Ireland. There’s also a description of the locale that “could wreck fucking havoc on a man’s prose if you let it.” Is this what happened to Barry when they signed the papers on the gaff?

“I remember the day we first came to look at the house here in Sligo, and I was looking out from the upstairs. There’s a kind of a landing that's big enough to put a desk on and there's a view of the lake and I was thinking, ‘Oh, man, that could fucking destroy me, it could all get very lyrical and sickly’. I'd have to face the desk into the wall.”

It could all go very W.B. Yeats very quickly.

Advertisement

“That was definitely the kind of concern I had,” Barry agrees

‘Whatever way this house was set down,’ Uncle Aldo tells his nephew about the property he’s leaving him, ‘I can’t explain it but the women go mental fucken gamey as soon as they get a waft of the place at all.’ I insist that Barry gives me the phone number of his estate agent immediately.

“I like this story, I wrote it very quickly,” Barry says, telling me nothing at all. “It’s just this bizarre notion of a kind of a sexy cottage, a place where people would find themselves getting into the mood, mysteriously. It kind of took care of itself quite quickly.”

Despite the guaranteed action, the nephew still puts the house up for sale.

“I think he realises at some level his own shocking level of inauthenticity, he's trying to be something he isn't. And he kind of accepts at the end that he is a maggot, just like his Uncle was before him. I think everything I write has characters trying to escape themselves, and trying to escape their own pasts, and realising that it's not possible. As a writer, I've been able to find both poignancy and black comedy in that.”

Finest Death Song

That Old Country Music really is an exceptional collection, and ‘Ox Mountain Death Song' is probably the best thing in it, a Hemingway iceberg of a story where you only see a small part of it above the waterline. Barry says more by saying less.

Advertisement

“It's kind of a Western in a lot of ways, an Ox Mountain, County Sligo take on the western with a glamorous young renegade and a bitter old sheriff. And there's even a ripe widow, so it has all the classic western motifs. The fun was to write it in in these tiny little numbered sections, almost like little chapters, and see how much of the scaffolding I could take out and still have it stand up. How much of the scenery and decor of a short story can you actually remove but leave the thing standing Like you're saying with the iceberg, how much can you keep submerged and still give the story pace and keep the reader going.”

“We live about thirty miles from there, and when we moved here first I started cycling a lot out around the Ox Mountains. It felt to me like there was a story for this place. I had a notion of a western in my mind. I was in the forecourt of the petrol station, just drinking a Capri Sun or something after getting off the bike one day. A squad car pulled in and a big, bitter looking, old guard got out and just sloped across the forecourt. And I thought okay, there's one character. I just need another one, and we're off.”

We’re back where we nearly started, the mountain the protagonists end up on is another character in that story, and you can see that ending coming too.

“From the start that story felt like a western and it felt like there was going to be blood on the floor at the end of it. I like to kind of play with sort of kind of classic genre stuff like the western or the classic crime novel or noir like in Night Boat To Tangier. Do them in an Irish accent, and bring them into unusual places.”