- Opinion

- 31 Dec 21

To quote the venerable Mr Joyce, “life is too short to read a bad book”. Here, then, are a selection of some of the good ones – chosen by our own half-blind blowhard, Mr Pat Carty - that landed in 2021.

"Fill your house with stacks of books, in all the crannies and all the nooks." - Dr. Seuss. Theodor Geisel, it turns out, was a not a real doctor, but it's a good prescription nevertheless. P.J. O’Rourke advised us to "Always read something that will make you look good if you die in the middle of it," which is sage counsel too.

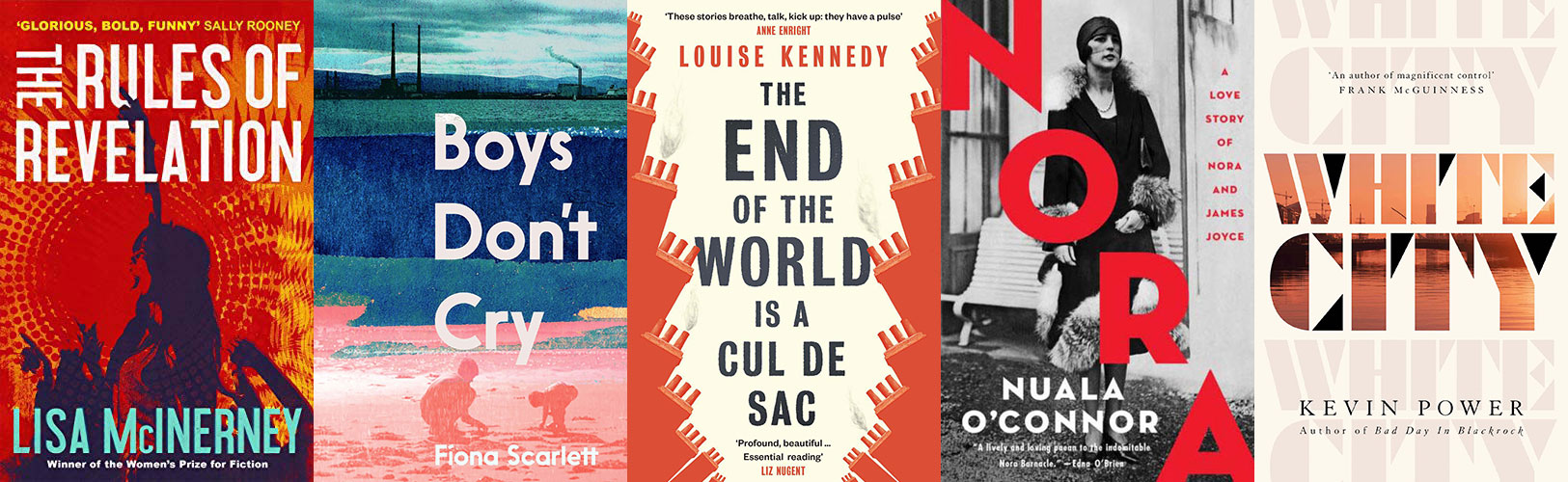

Irish Fiction

The End Of The World Is A Cul De Sac – Louise Kennedy (Bloomsbury Publishing)

Outrageously good storytelling in this collection of shorts, whether it be about the aftermath of failed housing estates, post-cancer holidays in the pissing rain, or using old family photos for a bit of time-travelling. There are stalkers, healing hands, a donkey, and a possibly mystical member of the Leporidae family, but the cake is taken by the recognition of a droopy eye on a television set in ‘In Silhouette’, the pain - and the guilt at the pain - of having a child that’s different in ‘Brittle Things’, and the baby that was never meant to be in ‘Garland Sunday’. It’s also “full of riding”, as Kennedy said herself, which is always a bonus.

Advertisement

Nora: A Love Story of Nora Barnacle and James Joyce – Nuala O’Connor (New Island Books)

Not only is this a beautifully told love story - romantic as well as earthy, for Nora and her Jim and his “maneen” were right goers - it also displays the breadth of O’Connor’s learning. I suspect she made it all the way through Ulysses at least once. Her Nora hilariously couldn’t give a fig for Joyce’s mush and the great author himself comes across as more than a bit of an arse. A genius like Joyce is easy to admire, but imagine having to live with him? Nora emerges as a person of remarkable strength, and patience. She was both muse and midwife to his achievements. He owed her everything.

White City – Kevin Power (Scribner)

I like a few bob as much as the next fella (“you’re in the wrong job so!” – Ed.) but the greed displayed during the Celtic Tiger wasn’t a good look on any of us. It’s hard, if not impossible to feel much sympathy or affection for anyone in Power’s romp through those strange days when it rained money, especially his narrator Ben, a “terminally upper-middle class” spoilt brat who reckons he can pull a fast one on everyone with a dodgy land deal that’ll grant him his ticket to the sun. You’ll be cheering on the arrival of the imminent financial crash.

Boys Don’t Cry – Fiona Scarlett (Faber)

When I read the blurb on this, which promised a story that “will break your heart in a million different ways”, I moaned aloud, “Do I have to?”, but I was, as so often happens, stupidly wrong. Joe has an avenue of escape from The Jax tower block where he’s grown up, although events drag him towards the dodgy world that his bad-egg Da is part of. Meanwhile, younger brother Finn’s worsening condition pulls down the sky down on both the good and the less so. If you’re not bawling by the end of this then you are made of sterner stuff than I.

Advertisement

The Rules Of Revelation - Lisa McInerney (John Murray)

Oh Cork, so much to answer for. We can also thank the real capital for the work of Lisa McInerney, in which the city takes a central role. The Rules Of Revelation concludes the (Blarneytown?) trilogy she began with her gang-of-Cork-heads introducing, multi-prize winning The Glorious Heresies, and then continued by positioning pill-pushing-pianist Ryan Cusack centre stage in The Blood Miracles, moving the action out of the rebel county to Naples. Cusack is back in Cork to record an album with his band, Lord Urchin, but the past – personified by Georgie, or Mel’s Ma, amongst others - won’t stay in the past. Niall Stokes called it, “a riveting and essential read,” and – contractually – I can’t argue with him. McInerney also wins the coveted Hot Press Line Of The Year trophy for describing the “demented” Irish as “young and gifted and damp.”

Honourable Mentions:

The Garden – Paul Perry (New Island Books), Quiet City – Philip Davison (Liberties Press), Snowflake – Louise Nealon (Harper), 56 Days – Catherine Ryan Howard (Blackstone), The Killing Kind – Jane Casey (Harper Collins), Panenka – Rónán Hession (Bluemoose Books), The Sunken Road – Ciaran McMenamin (Vintage), April In Spain – John Banville (Faber), Midfield Dynamo – Adrian Duncan (The Lilliput Press), The Magician - Colm Tóibín (Penguin), Iron Annie – Luke Cassidy (Bloomsbury Circus), The Pawnbroker’s Reward – Declan O’Rourke (Gill), Life Without Children - Roddy Doyle (Jonathan Cape), The Ballad Of Lord Edward and Citizen Small – Neil Jordan (The Lilliput Press), In The Event Of Contact – Ethel Rohan (Dzanc Books), The Echo Chamber – John Boyne (Doubleday), A Shock – Keith Ridgway (Picador), Line – Niall Bourke (Tramp Press), Beautiful World, Where Are You - Sally Rooney (Faber)

Anthology/Brick Of The Year

Shadow Voices - 300 Years Of Irish Genre Fiction: A History in Stories – Edited by John Connolly (Hodder & Stoughton)

In a way, this is the perfect lockdown book, a complete college course in one volume wherein one of the world’s great thriller writers details the history of Irish genre fiction – his collective appellation, not mine. Starting off with Swift suggesting we eat the poor and then meandering all the way to the “domestic noir” of Liz Nugent and Maura McHugh’s Yeats-inspired revenge tree, there is eating and drinking – of blood, on occasion – in this mammoth tome, which can also be used as a steps when changing lightbulbs. Double points for Connolly as this year’s The Nameless Ones was fairly handy too.

Advertisement

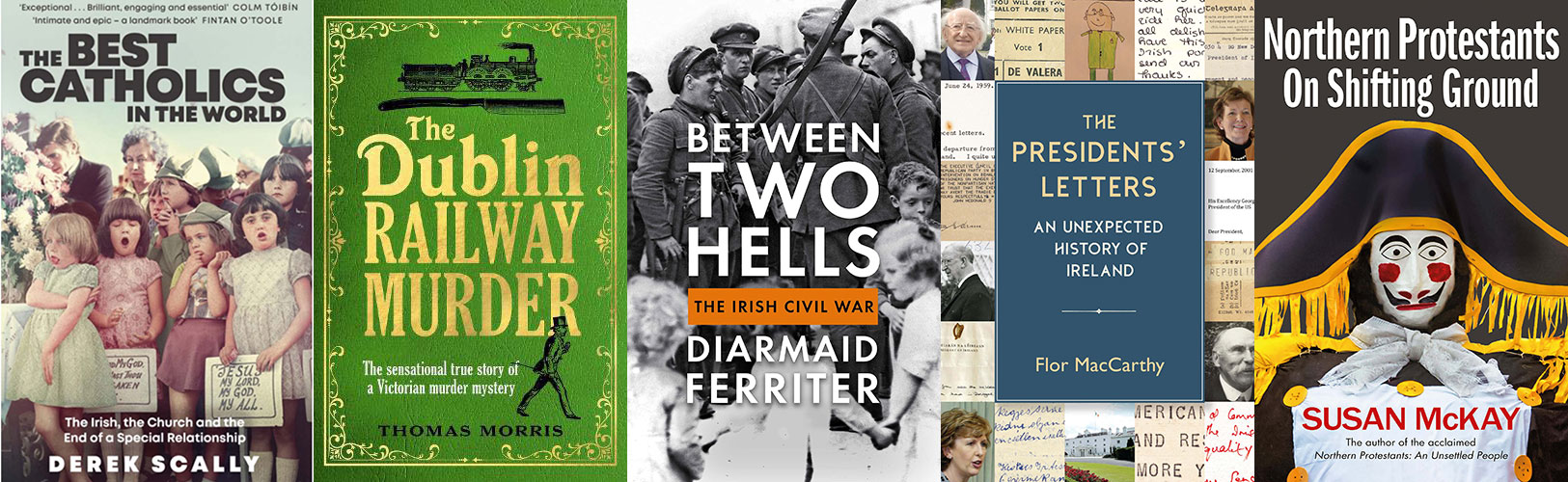

Irish Non-fiction

Between Two Hells: The Irish Civil War – Diarmaid Ferriter (Profile Books)

The eminent historian’s timely examination of the treaty signed one-hundred years ago this very month that created the Irish Free State and the aftermath of this compromise that would cause the country to descend into civil war just over six months later. As meticulously researched as one would expect, Ferriter’s follow-up to A Nation And Not A Rabble – there is some cross over – not only details a damaging conflict that, as the cliché goes, pitched brother against brother, or “criminals” versus “materialists” as the opposing sides would have it, but also thoroughly examines the long shadow it cast over the nation’s development. Ferriter’s stated aim was to “humanise their dilemmas and the deadly consequences of their decisions,” and he does just that.

The Presidents’ Letters: An Unexpected History of the Irish State - Flor MacCarthy (New Island)

A good idea brilliantly executed, McCarthy compiles letters to and from the big house in the park, coupled with several essays on the presidency itself. First, and perhaps most illuminating, amongst these is 6.1 man – and Springsteen nut - David McCullagh’s rough guide to the presidents, a handy reminder for those of us who haven’t been in school for a long time. The letters are the stars though, ranging from de Valera and Cosgrave’s unlikely joining of forces to offer the office to Douglas Hyde in 1938, to the hats off- warranting behaviour of Queen Elizabeth II, who signs off a letter to Mary Robinson with “your good friend, Elizabeth R” and insists on trying the cúpla focal during her 2011 visit with help from some phonetic scribbling courtesy of Mary McAleese.

Advertisement

The Best Catholics In The World: The Irish, The Church and the End of a Special Relationship – Derek Scally (Penguin Sandycove)

On a yuletide trip home to Dublin from Germany, Scally - the Irish Times’ man in Berlin – goes to Christmas Eve mass in Raheny and finds the attendance less than marvellous. This flicks on a lightbulb over his head so he takes in a variety of masses and novenas – rather him than me – and conducts extensive interviews to detail the history of the Catholic church in Ireland and how it lost its suffocating hold on us. In his examination, Scally makes reference to the German people’s acceptance of the notion of ‘collective shame’ and how such an idea could be applied here in the light of the Mother and Baby Home Commission’s report and the various other crimes perpetrated by the agents of the church. Thank God they’re nearly gone.

Northern Protestants: On Shifting Ground – Susan McKay (Blackstaff Press)

McKay grew up in 60s Derry amongst protestants who, as she says in her prologue, “Would not yield… Would not bend the knee… and… would fight.” How does that figure now that, as McKay points out, the demographics of Northern Ireland have shifted and, in a post-Brexit society, with Sinn Féin doing well, there is the possibility of the notion of a united Ireland at least making it to the discussion table? As with her previous book, Northern Protestants: An Unsettled People, McKay talks to people from every walk of society, some who bemoan the national question being put over all other social issues, and some who feel that things have improved, somewhat. Overall, it offers a differing view from the DUP rhetoric on the evening news.

The Dublin Railway Murders – Thomas Morris (Penguin)

A true crime story that reads like a good novel , Morris - a Welsh man, but educated here, so we’ll allow it – takes us back to 1856. The beaten and bloodied body of the chief cashier of the Midland Great Western Railway is found in his office in Broadstone Station (the city side of modern Phibsboro). The door is locked from the inside and substantial amount of cash is left untouched. Scotland Yard is left scratching its collective head so it’s up to Irish detective Augustus Guy. Morris’s admirably meticulous research allows to him to not only present a fascinating case, which gripped Irish society in its day, but also to paint a portrait of Victorian Dublin.

Advertisement

Honourable Mentions

Four Years In The Cauldron – Brian O’Donovan (Penguin), Keep Calm And Trust The Science – Professor Luke O’Neill (Gill), Returning Light – Robert Harris (Harper Collins), A State Of Emergency – Richard Chambers, What White People Can Do Next - Emma Dabiri (Penguin)

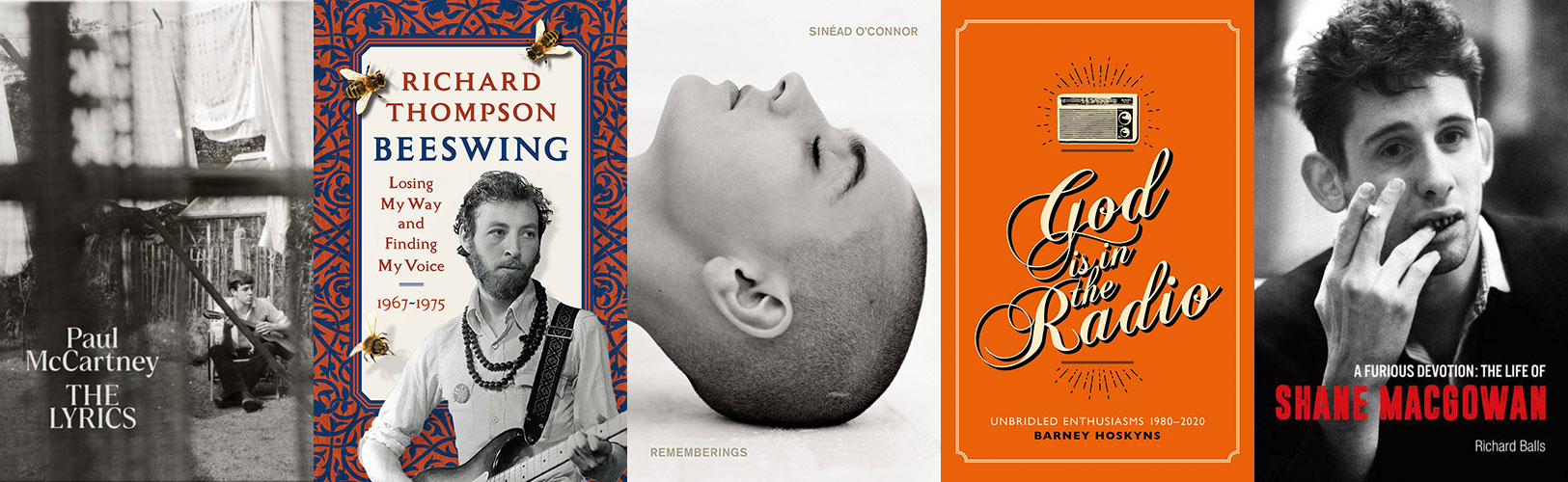

Music

The Lyrics – Paul McCartney (Allen Lane)

In a year when all things Beatles steamrolled over us repeatedly, McCartney’s book still has to take the top honours. The world’s greatest songwriter – probably - tells his story through the songs themselves, using a compendium of his immortal tunes to spark reminiscences, from before anyone knew who he was, right up to now when there’s no escaping him. On top of that we get hundreds of beautiful images, many previously unseen from his own archives, and another great Paul, Mr Muldoon, keeps it all flowing. The pride of any coffee table, as long as you reenforce the legs, it’ll cost you as much as ten other books on this list but it is worth every penny.

Advertisement

Rememberings – Sinéad O’Connor (Penguin)

Whether you’re a fan or not, the hat has to come off to Sinéad O’Connor for sticking resolutely to her guns, and both barrels are employed here. The book revolves around – and O’Connor sees herself as speaking with two different voices either side of - the night she tore up the picture of the Pope on Saturday Night Live in protest at Church child sex abuse. Now, of course, we know she was right, but back then this was as brave a move as any “rock star” had ever made. As O’Connor sees it, having a worldwide number one was the aberration, the pope move was what she was really supposed to be at. With the candour you’d expect – and with that you mightn’t - she details everything from her difficult childhood, to bad experiences with Prince and industry bigwigs, to worse ones with her own mental well-being. What emerges is proof positive that no one is more punk than Sinéad O’Connor.

A Furious Devotion: The Authorised Story of Shane MacGowan – Richard Balls (Omnibus)

Balls gets the inside story, slurred and hissed straight out of the horse’s mouth, on the life of MacGowan, a fiercely intelligent man responsible for some of the greatest songs of the last thirty-five odd years. Balls is very obviously a fan but that doesn’t stop him delivering a warts – of which there are many – and all recounting of the life of the man who was displaying brilliance when he was still a child, changed the perception of Irish music with some immortal songs and records, and ultimately pissed it all up a wall because that’s what he wanted to do. Balls may claim that “MacGowan is not done yet” but the evidence presented in this ironically sobering tale says otherwise.

God Is In The Radio: Unbridled Enthusiasms 1980 – 2020 - Barney Hoskyns (Omnibus)

A “greatest hits” of sorts from the always excellent Hoskyns, forever welcome at my table thanks to Say It One Time For The Broken Hearted: Country Soul In The American South, these are pieces about “the music I’ve loved the most”. Of course I’m going to nod in agreement when he reiterates how great the music of Al Green and Burt Bacharach is, and I too “could listen to George Jones for all eternity”. What’s more impressive, however, is a journalist asking Keith Richards a real question, being reminded of the brilliance of Luther Vandross and Björk’s ’Hope’, and very nearly being tempted to give Joy Division another try. Nearly. Like music? Buy this.

Advertisement

Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice 1967-1975 – Richard Thompson (Faber)

In which the genius songwriter and one of the world’s greatest guitarists rifles though the “dusty attic” of his memory and recalls his crucial part in the creation of a very British type of rock music. As he told Hot Press this year, “Fairport [Convention] were trying to build a bridge between traditional and popular music, because that link had been lost.” Tragedy sits beside triumph in the Fairport story and Thompson details that too, as well as his series of albums with wife and partner Linda and the place that Sufism came to occupy in his life. As beautifully put together as his best songs, and that’s saying something.

Honourable Mentions

Shared Notes: A Musical Journey – Martin Hayes (Doubleday Ireland), Last Chance Texaco – Rickie Lee Jones (Grove), Looking To Get Lost – Peter Guralnick (Little & Brown), Unrequited Infatuations – Stevie Van Zandt (White Rabbit)

Advertisement

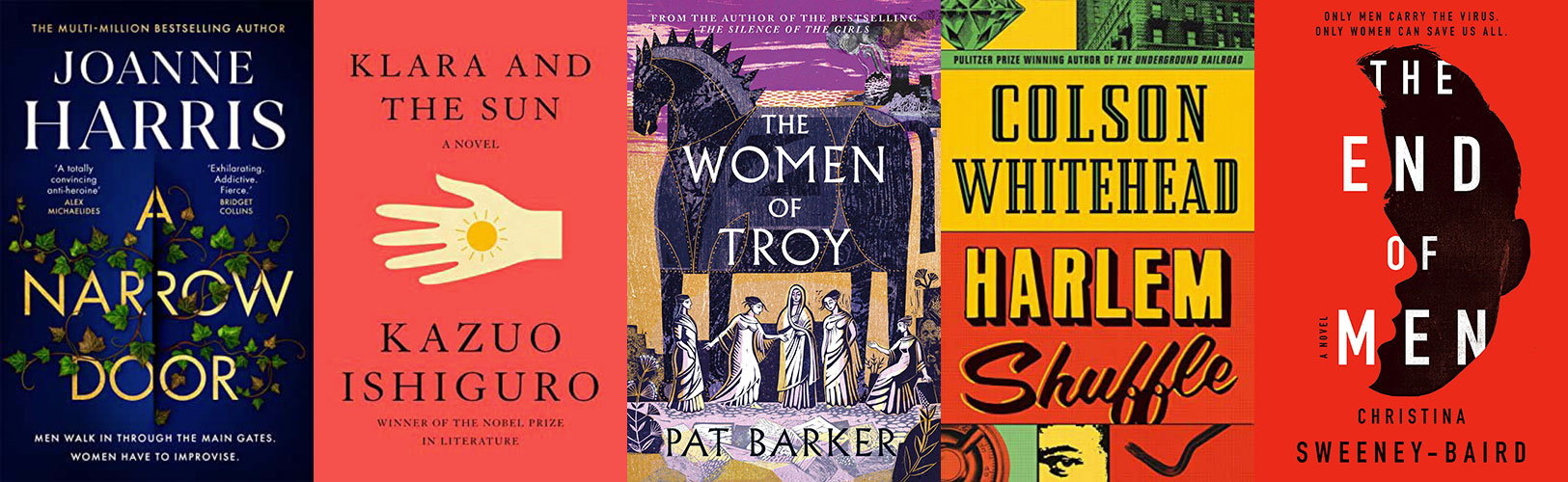

International Fiction

Harlem Shuffle – Colson Whitehead (Fleet)

Multi-Pulitzer winner Whitehead changes tack from his last two works – escaping slavery in The Underground Railroad, escaping reform school abuse in The Nickel Boys - for something, in comparison at least, a bit more light-hearted, although the author still manages to get in some pointed social commentary, about escaping your assigned rung. “Ray Carney is only slightly bent when it comes to be being crooked,” but then you have to be a little bent to move up in the mid-20th century Harlem – and the borough is a character as much as anyone else. Ray’s a good guy but he’ll do what he has to in what is ostensibly a crime novel, which may seem slightly at odds with Whitehead’s previous output, but he makes it his own.

Klara And The Sun – Kazuo Ishiguro (Faber)

Klara’s an android or “Artificial friend”, purchased as a companion/helper for the unwell Josie, who suffers from the same aliment that already claimed her sister. Through Klara’s eyes – which deliberately register things differently than our own – this new world is slowly revealed. Some children have been “lifted” – genetically modified – and some haven’t, and the presence of artificial life is not welcomed by everyone. Are the people who complain about Klara’s presence really in fear of their own obsolescence? To borrow a phrase from Ishiguro’s Nobel citation, does the view through these artificial eyes remind us of “our illusory sense of connection with the world”? A novel you’ll be mulling over long after you’ve finished it.

Advertisement

A Narrow Door – Joanne Harris (Orion)

Rebecca Buckfast has recently been made headmistress of St. Oswald’s, a posh boys school. She’s just one of the changes that’s ruffling feathers and her own plumage is being disturbed by events from her past coming back to haunt her. You’ll be instantly brought to attention by her admission of two murders as early as the preface in this thriller that’s also an examination of how women have to contort themselves to squeeze through the title’s aperture with a plot that thickens with every page. Rebecca pieces together her own story but she’s also revealing it – piecemeal - to Classics Master Roy Straitley, so can she be trusted in the first place, and where do the rivers of the ancient Greek underworld come into it, and who’s Mr Smallface? Good luck putting this down.

The Women Of Troy – Pat Barker (Penguin)

In a follow-up to the equally great The Silence Of The Girls, Barker is again retelling the myths told by Homer – and used as a cornerstone to construct Western civilisation and art – through female eyes. Troy has fallen and our narrator Briseis, who had been Achille’s prize but is now, because of Paris’ arrow, married to another, witnesses the strength of the women in the camp, who carry on despite their treatment under the Greeks. Pyrrhus, son of Achilles, has angered the Gods with a dishonourable act so they refuse to fill the sails that wish to cross back over the Aegean Sea. Barker uses characters like him – although, to be fair, he had big sandals to fill – to illustrate the paper-thin fragility of the male ego.

The End Of Men – Christina Sweeney-Baird (Putnam)

Stop me if this sounds familiar but it’s the year 2025 and a viral outbreak sweeps across the world, claiming victims from every social strata. The twist here is the bug only affects men, women can be carriers but it has no physical effect on them. The first half is a gripping thriller, but it is the transfer of power that is noteworthy. The few surviving men are now scared of women. “My mere physical presence is enough to terrify someone into running. No wonder they used to get drunk on it,” is how one character puts it. Told through diary first-person diary entries, we witness a world – everything from international politics to dating apps – adjusting to this new reality. This novel’s thunder was somewhat stolen by a vastly inferior TV show but you should seek it out.

Advertisement

Honourable Mentions

Crossroads – Jonathan Franzen (Fourth Estate), Silverview – John le Carré (Penguin), Oh William! – Elizabeth Strout, The Last Thing To Burn – Will Dean (Hodder & Stoughton)

International Non-fiction

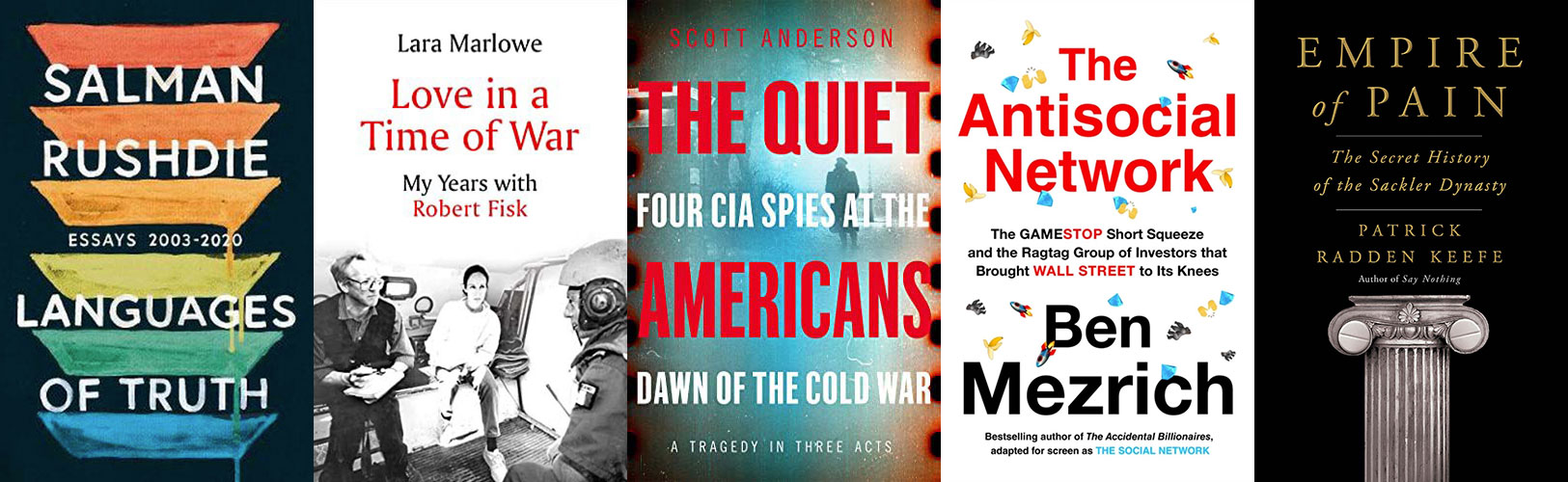

Love In A Time Of War: My Years With Robert Fisk – Lara Marlowe (Apollo)

Fisk was already a renowned Times journalist who had covered Northern Ireland and was working the Middle East beat when Marlowe, who was only getting started in the fourth estate, met him in 1983. The locations and the events of their next couple of decades together are the stuff that international thriller writers can only dream of; whether it be Islamist revolt in Algeria, both US assaults on Iraq – Fisk was famously critical of Uncle Sam’s foreign policy in the region, or hellish times in Lebanon or the former Yugoslavia. Their love for each other endured even after their marriage ended, but what is even more admirable is the book’s portrayal of journalists - Marlowe took up with the Irish Times after quitting her previous post at Time Magazine in protest over editorial queasiness - for whom the truth was always paramount.

Advertisement

Languages Of Truth: Essays 2003-2020 – Salman Rushdie (Jonathan Cape)

Not satisfied with being one of the greatest living novelists – 2019’s Quichotte is brilliant, for a start – Rushdie is also the kind of critics that other critics dream of being when they grow up. In the light of The Plot Against America, he refers to Philip Roth as “a Cassandra for our age, warning us against what was to come”. He acknowledges the difficulty of Samuel Beckett’s Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable trilogy of novels, but advises surrender, “Give into the text and it opens up, a rare if shabby flower.” And it’s not all highfaluting either; there’s a lovely appreciation of his late pal, Carrie Fisher, and an account of catching the coronavirus and realising how lucky he was to survive to tell the tale. Marvellous.

The Quiet Americans: Four Spies At The Dawn Of The Cold War – Scott Anderson (Picador)

A broad and brilliant look at the early years of the C.I.A. after its emergence from the ashes of both the second world war and the Office Of Strategic Services, and the first decade of its fight against communism, told through the adventures and misadventures of the four men in question. Anderson is no flag waver and concludes that the agency’s machinations led to “the fall of the United States’ moral standing in the world… the final laying bare of the myth of America as the herald of freedom”. It’s hard to disagree once you’ve worked your way through this utterly engrossing piece of work.

Empire Of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty – Patrick Radden Keefe (Picador)

Keefe, a staff writer for the New Yorker, builds on a 2017 essay to tell the story of the Sackler family, one of the richest in the world, and their part in the opioid epidemic in America through their ownership of Perdue Pharma and its flagship product, OxyContin, aggressively marketed despite the warnings that it was highly addictive. It’s hardly shocking, but it’s alleged that the FDA granted approval to OxyContin possibly because of an inside man who later went to work for Purdue. This approval would later be referred to as “one of the worst medical mistakes.” Eventually, the company goes into bankruptcy but the family get to keep all but a tiny percentage of the money. The rich stay healthy and the sick stay poor.

Advertisement

The Antisocial Network - Ben Mezrich (Harper Collins)

Sometimes, the little guy does catch a break, as in this unlikely tale a group of mostly amateur investors, on a forum called WallStreetBets, who spotted an opportunity in GameStop, a video game seller that was barely hanging on in the age of downloads. Using Robinhood, an app that allowed common folk to trade stocks but avoid brokerage fees, they drove the stock’s price to ridiculous heights, costing the difficult-to-pity Wall Street firms billions. I’m no economics expert but Mezrich manages to explain concepts like short squeeze in a way that I almost understood. Basically the suits had made huge bets against the company. In an attempt to cut losses, they try to buy up escalating shares but the commoners refuse to sell, driving the prices up further, before Robinhood turns Sheriff Of Nottingham and imposes restrictions. Money is an odd yoke.

Honourable Mentions

The Confidence Men – Margalit Fox (Profile Books), Shackleton: A Biography – Ranulph Fiennes (Michael Joseph/Penguin), Soldiers: Great Stories of War and Peace – Max Hastings (Harper Collins), Helgoland – Carlo Rovelli (Allen Lane)