- Culture

- 29 Jul 22

The Hot Press Interview: The Abbey Theatre directors Caitriona McLaughlin and Mark O’Brien

Having taken over the Abbey Theatre last summer at a time of major upheaval, co-directors Caitriona McLaughlin and Mark O’Brien were guaranteed an eventful start to their tenure in the national theatre. They discuss recent controversies, creating a new vision for Irish theatre, problematic plays, social media, funding and plenty more besides. Portraits by Miguel Ruiz.

The Abbey Theatre’s new directors, Caitriona McLaughlin and Mark O’Brien, have taken charge at a time of considerable upheaval for the national theatre. In January 2019, the Abbey – founded in 1904, making it 73 years Hot Press’ senior – found itself at the centre of controversy when theatre professionals issued a public letter of concern about the theatre’s then-model of production, and its perceived negative impact on the wider theatrical ecosystem in Ireland.

Late last year, accountancy firm Mazars was asked to review finance and governance at the Abbey, following media reports that the theatre’s handling of the departure earlier in 2021 of ex-chief executives and co-directors, Graham McLaren and Neil Murray, had led to a number of settlements to the the former directors, totalling around €700,000, including legal fees.

When Hot Press spoke with McLaughlin and O’Brien in their Abbey office in early June, the Mazars audit was ongoing and the duo were limited in what they could say on the matter. In mid-June, the Irish Times reported that following the audit, the Arts Council-approved funding for the national theatre this year, of €7.5m, has a number of conditions attached.

Caitriona McLaughlin and Mark O’Brien by Miguel Ruiz.

Caitriona McLaughlin and Mark O’Brien by Miguel Ruiz.These conditions “seek to safeguard the expenditure of public monies now and into the future”, and involve “reviews of policies and procedures”, in “procurement, HR and behaving with integrity, leading people, working effectively and being accountable and transparent”. According to the Irish Times report, the conditions for funding also cover “monitoring and reporting on board appointments; information on co-productions and the cost base for the Peacock Theatre; and ‘a culture audit of the organisation’.” For its part, the Abbey “has signalled its full commitment to working with the Arts Council to ensure these conditions are satisfied.”

In terms of the respective backgrounds of the new Abbey duo, Donegal native McLaughlin has directed an extensive array of productions at home and abroad, with her Stateside work including a stint with a theatre troupe headed up by the late great Philip Seymour Hoffman. Bray native O’Brien, meanwhile, came to the Abbey from Ballymun Axis Theatre.

Taking charge in July of last year, the duo first had to steer the theatre through the choppy waters of Covid, before devising this year’s spring programme, which touched on the centenary of the State’s founding, as well as topics like race and social change.

As the man says, it was plenty to be getting on with. All of this and more was on the agenda during the Hot Press deep dive.

Audiences have a lot of options for entertainment these days. How have you found the challenge of attracting them to the theatre?

Caitriona McLaughlin: It’s the age of everything that’s all the same, because it’s not live – except for theatre and live gigs. Nothing will ever replicate those experiences. People may choose different distractions, but they will never have an experience that comes close to a live event – sitting in a room in the dark with 500 or 1,000 people, with their hearts beating in time, and everyone going on the same emotional journey. And everyone having 500 individual reactions to a word, a phrase or a character. It only happens that night. It’s never replicated again, because it has a different impact on another audience the next night. We’re designed as human beings to respond to being together – to understand our humanity through looking at each other. For me, nothing will ever come close to live theatre for that. It’ll exist regardless of what is invented.

There are other aspects as well.

CM: The other thing about theatre is that, because it’s fictionalised reality, it gives you enough distance to be able to respond to it in whatever way you want. There’s a massive freedom in that, and psychologically, that’s very different. A lot of people say, ‘Reality TV is much better because it’s more real’. But it’s not much better, because it doesn’t have that distance. If you do something on reality TV and I attack you, I’m attacking you. If a character expresses exactly the same thing, there is freedom in me attacking a character. So there is a much more important, truer, genuine dialogue with theatre than there can ever be with a live argument. That’s really important – that’s it’s real function in how we understand ourselves as human beings.

Conor McPherson is now involved as senior associate writer.

CM: He’s contributing to our design of a literary department, or a new work department, which is probably a more accurate way of describing it. He contributes to script meetings, reads plays and offers feedback. We have conversations with him around different kinds of plays and ways to support writers. He’s working with someone at the moment, helping them develop a kind of semi-biographical piece of work. He contributes in loads of different ways. We haven’t got the full spectrum yet, but we’ll get to it eventually.

What was the idea behind having him involved?

CM: We wanted to set a bar in terms of what the expectation is, and the expectations writers can have for themselves. Marina Carr is also involved as a senior associate writer. Marina and Conor are both very energetic, very engaged playwrights. A lot of playwrights spread themselves across TV, film, different forms. I know Conor writes films as well, but he and Marina are primarily playwrights, that’s their passion. That’s a really important distinction for me, because writing narrative drama for theatre is very specific. It’s present tense action. The thing that makes a good live experience is very different from what makes a good novel, poem or film. So I wanted two people at the top of their game who were committed specifically to playwriting, and who were contemporary and reinventing themselves.

How did you go about selecting works for the spring programme?

CM: The starting place for me is always the here and now. What’s going on with me personally? What’s going on with the organisation? What’s going on with society in general? The big thing that felt very present was the sense of transition. Covid had done something to us as a society, the organisation had been quiet for a year or two. In one way or another, we were in a transitional phase. That fed into my thinking around programmatic decisions, and the phrase that kept coming back to me, was that I wanted to look at who we are, who we were and who we want to be. Those were the ideals. The other things that were important were that I would engage with new writers and artists. But also that it would be built on the foundations of the canon and the historical work that was here.

Which is quite a lot…

CM: We have an incredibly rich resource in terms of the plays and the playwrights that come from Ireland. All those things fed into the programme, but you couldn’t get away from the fact that we were coming into 100 years since partition. That in itself is a big transition. We’re moving beyond the 50th, 60th and 75th anniversaries. It felt like Ireland no longer had to define itself in opposition to England, or in opposition to anything else. So there’s a lot of questions there around identity and who we are as a nation. And does a nation even mean anything anymore? Does it matter if we identify with nationality?

How did you answer that question?

Marina Carr is a really significant international playwright who has always pushed the boat out. For me, she has re-defined Irish plays, because she’s more dangerous to me than anybody else. Starting with her was really important, because of how she exposes humanity in her plays. Then, I suppose Brian Friel’s Translations – which she’s directing in the summer – is a significant Irish popular play. But for me, it’s also a starting point and a provocation around a conversation with the UK, in terms of how that relationship has evolved, how partition happened. And how this oppressive, imperialist nation has impacted who we are as people.

Marina Carr.

Marina Carr.What else were you keen on?

CM: An Octoroon was one of the first plays I wanted to put in the programme, because I felt that, when we’re looking at identity, nobody did that in a more interesting way than Dion Boucicault and his obsession with stereotypes. And how Irish people were presented and represented negatively in British theatre of the day. He’s trying to re-define it but still maintain the comic tropes, and work into that big melodramatic structure. And then, the impulse of using theatre to examine a very topical, hard, ugly state that was slavery, and the question around slavery at the time. Looking at it with a contemporary lens, how he got it so wrong. Because he built that play on stereotypes of Africans and Black Americans. Then to have a contemporary playwright, a young Black man, take on a play that is – for him and his culture – potentially offensive, potentially degrading, and to respect the writer, respect the impulse enough to break it open, and turn it into a play about racism.

You found it a powerful work.

CM: Branden Jacobs-Jenkins turned it into one of the most shocking, as well as one of the most hilarious, pieces of theatre. To engage artistically with that much respect for something that you are directly in opposition to is incredibly exciting. Because I am so frustrated with the polarisation that’s happening in the world at the moment. You’re for it or you’re against it. To find artists like that who have come in sideways, cracked something open and who have that much respect for another artist, is so exciting. I wanted to put that on, partly because it’s a moment in Ireland where we need to look at racism, and we need to examine who we are now. We are changing as a culture, and we are ignoring that fact a little bit. Certainly outside of Dublin, we are. So we need to ask ourselves, have we embraced this change in a really helpful, positive way or not?

Branden Jacob-Jenkins.

Branden Jacob-Jenkins.You’re still getting started.

Mark O’Brien: It’s a moment where it’s the beginning of something, it’s scene-setting for us. An Octoroon, as Caitriona rightly said, is doing that work. But also on a very internalised level, and in our discussions as co-directors, we are exploring what that word ‘diversity’ actually means. By using that word, are we defining what’s normal? Who gets to define normality? All these tropes that are in the world at the moment, particularly in Irish society, need to be examined a bit more. Having this work on our stage forces us, in a very good way, to re-examine ourselves. Narrative springs from somewhere, so with An Octoroon and Translations, there are many conversations which we might think are in the show, but someone else might have a completely different relationship to it. Watching An Octoroon with an audience, it’s fascinating watching different people and how they take the show, depending on their background, what their knowledge base is.

The subject of co-productions has proven controversial for the Abbey. I think there was only one in the spring programme. Was that a conscious decision?

CM: It’s not really about co-productions, it’s about the nature of them. What happened in the past is that there was a belief that certain co-productions reduced the pool of work. Now whether or not that’s true, I don’t know. I haven’t investigated that fully. But we are very specifically doing the opposite. We are getting engaged in co-productions that widen the pool of work. So for example, we’re doing a co-production with the Lyric. It allows us both to do something on a much bigger scale; it allows us to offer much bigger contracts to actors. It takes those actors out of the pool for a much longer time, so it leaves space for other actors. It doesn’t do any of what happened before.

The Abbey has been at the centre of a few different controversies recently. Having such high-profile positions, do you live in fear of the day you’re trending on Twitter?

CM: Just because somebody says it doesn’t mean that it’s true. You cannot legislate for what people want to believe or who they want to follow. Twitter and social media is a minefield. And I’m terrible at it! I’m popping in and out every couple of weeks and trying to engage with it. But I don’t think that we can be brought to a place of accepting such binary, narrow frameworks to live our lives through. I personally am going to resist it with everything I’ve got.

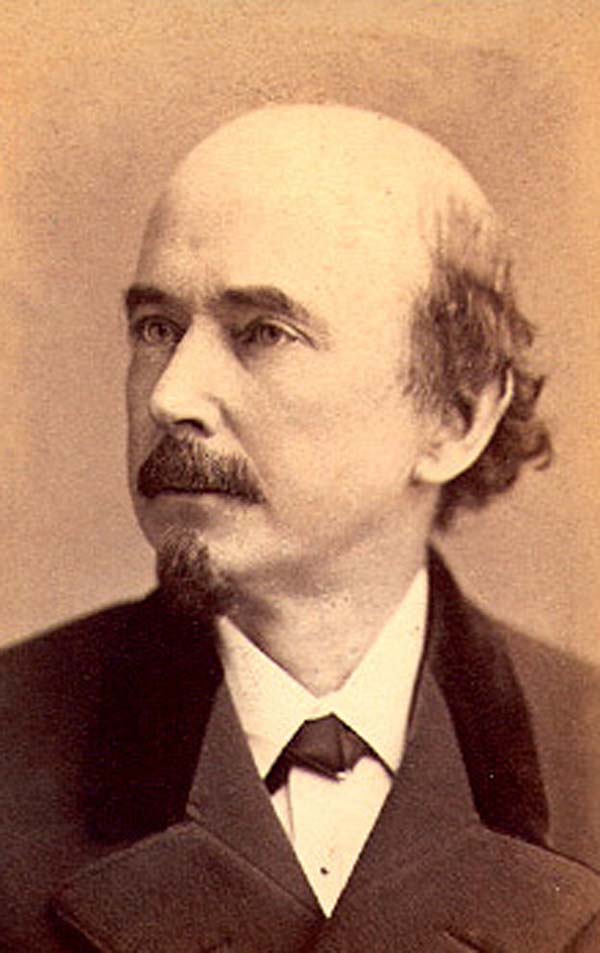

Dion Boucicault.

Dion Boucicault.Growing up as Gen Xer in the ’90s we wanted to be shaken and even occasionally shocked by art. Does this figure in your thinking now?

MOB: That’s back to a binary space. At that time in Ireland, there was a hammer being brought to a lot of stuff, a lot of change. We all knew it was lying there underneath, and that hammer had to be brought out. Now, there are really interesting things that dig deeper and last longer in relation to the way things change. The difference for me is being reactionary towards something, and really interrogating something to find out where we’re going. So that value of saying, ‘That’s all wrong’ – where are we actually going? How do we find a space where we can even explore where we’re going, when we’re all shouting about what we don’t want? That process of watching play rehearsals and interrogating a piece of work, it’s the same thing.

People are now re-evaluating old films and finding some problematic. Are you encountering that in theatre?

CM: Totally. Dion Boucicault is problematic. There’s two options – you can never do that play again, which is what most people do. Or you can do what Branden Jacobs-Jenkins did and reframe it, contextualise it, and actually make an even greater piece of art that allows the play to challenge its own narrative. It allows the audience to understand something fundamentally about itself, because of the tension between the frame and the original.

MOB: The truth aspect of what’s in the world at the moment: you can’t rewrite history. You can’t go, ‘Well, that never happened, so we’re not going to explore that’. What we were saying about the different frames – slavery happened. So it can’t be like, ‘Well, we can’t talk about that now’. One aspect of An Octoroon, in the very beginning of it, the character – in the guise of the playwright – talks about that, about how he couldn’t get white people to play slave-owners. We’re only going to move on beyond mistakes and things that weren’t right when we own them. Ireland has a lot to learn in that way, rather than trying to go, ‘That’ll never happen again’.

A scene from An Octoroon, and playwrights Branden Jacobs-Jenkins and Dion Boucicault.

A scene from An Octoroon, and playwrights Branden Jacobs-Jenkins and Dion Boucicault.The Abbey does well with funding. Do you feel it’s well-resourced enough?

CM: No!

MOB: There’s a couple of things there. As I was saying earlier, what happened during Covid was the public fully waking up to the importance of art in all our lives. But what also happened was that a huge amount of people were out of work in our sector, and a huge amount of people have left our sector because of that. What was brilliant to see was lobby groups that have been going for years – like the National Campaign for the Arts and Theatre Forum – were really heard by the Department for the Arts. That relationship has been transformed. The Arts Council were amazing in releasing funding early, and all these bursary schemes developed. So in relation to resourcing, the arts in Ireland – while still being quite low down on the European scale – has moved. The conversation about the Abbey is an interesting one. Factually, if Ireland wants a national theatre, it needs resources. It’s like another binary narrative, sometimes –it’s like if the Abbey is getting more, everyone else is getting less. That’s not the case. I think we need to be careful of that.

What about the return?

MOB: The Abbey would return nearly twice what it’s funded. That narrative needs to be spoken about. That goes across the whole sector; art feeds the economy in other areas. So when this place is active, all the restaurants around are getting business. And that goes for Ed Sheeran in 3Arena or whatever. It’s one of the few industries that when it’s spoken about, it’s almost spoken about singularly as a thing in itself. But if you were talking about any other business, they’re always talked about as this spiderweb. The arts plays a fundamental part in the life of the city. As it emerges out of Covid, things like the wage supports, the new basic income for artists, is phenomenal. Hopefully over the years, that will bleed into supporting people who don’t have the access to funding. People like technicians and stage managers are really delicately balanced.

I read a lot of books during lockdown, and at one point I ended up reading a play, Mercury Fur by Philip Ridley. I thought it was unbelievable, so daring, transgressive and haunting.

CM: It’s brilliant. I think it was here, in the Project last year.

Could you put it on, being an English play?

CM: Totally, why not? It’s a stunning play. Actually, maybe it was Venus In Fur they did in the Project. So they haven’t done Mercury Fur! Do you know who I saw doing that? The guy from Perfume, what’s his name…

Ben Whishaw?

Yeah – it was amazing.

Read more deep dive interviews and music news in our brand new, 45th anniversary issue.

RELATED

- Culture

- 26 Dec 25

EPIC: The Irish Emigration Museum back in full swing on 27 December

- Culture

- 24 Dec 25

The Best Books of 2025

- Culture

- 22 Dec 25