- Culture

- 03 Nov 22

Over three gigs the London Palladium, Bob Dylan and his band tapped into something truly remarkable. But what was it? And how can it be defined or expressed? That, as they say, is the million dollar question. Now read on to find the answer – or one version of it at least!

“I can’t sing a song that I don’t understand" — Bob Dylan, 'Goodbye Jimmy Reed'

Bob Zimmerman was just sixteen, listening to the radio and to new records with his friends in Hibbing, Minnesota, when Jimmy Reed was on the rise with a string of hits for Vee-Jay Records. Reed’s songs, which he often co-wrote with his wife Mary “Mama” Reed, typically begin with the wail of the harmonica as introduction, before his guitar and voice come in.

On 'My First Plea', with its racy, dirty, gritty lyric “Don't pull no subway, I rather see you pull a train/ You know I love you, love ya baby, girl, ya know it's a cryin' shame.” On 'The Sun Is Shining', with its sexy boogie beat. On 'Honest I Do', with its classic blues plaint “Please tell me you love me/ stop drivin’ me mad.”

'Big Boss Man' is Reed’s 1960 song about which Dylan writes in his just-published The Philosophy of Modern Song. He calls Reed “the essence of electric simplicity,” and says “None of his songs ever touch the ground.” These are songs that Bob Zimmerman understood then – and that Bob Dylan, currently sharing with us live all his newest songs, their roots in the music he loves most, understands even better now.

The rollicking, rocking 'Goodbye Jimmy Reed' is the song from his 2020 album Rough And Rowdy Ways that Dylan is performing in the penultimate spot on his current tour of the same name – except in Nottingham, where on October 28 he added 'I Can’t Seem To Say Goodbye' to his set-list in honour of Jerry Lee Lewis, who had died earlier that day at home in Mississippi.

Advertisement

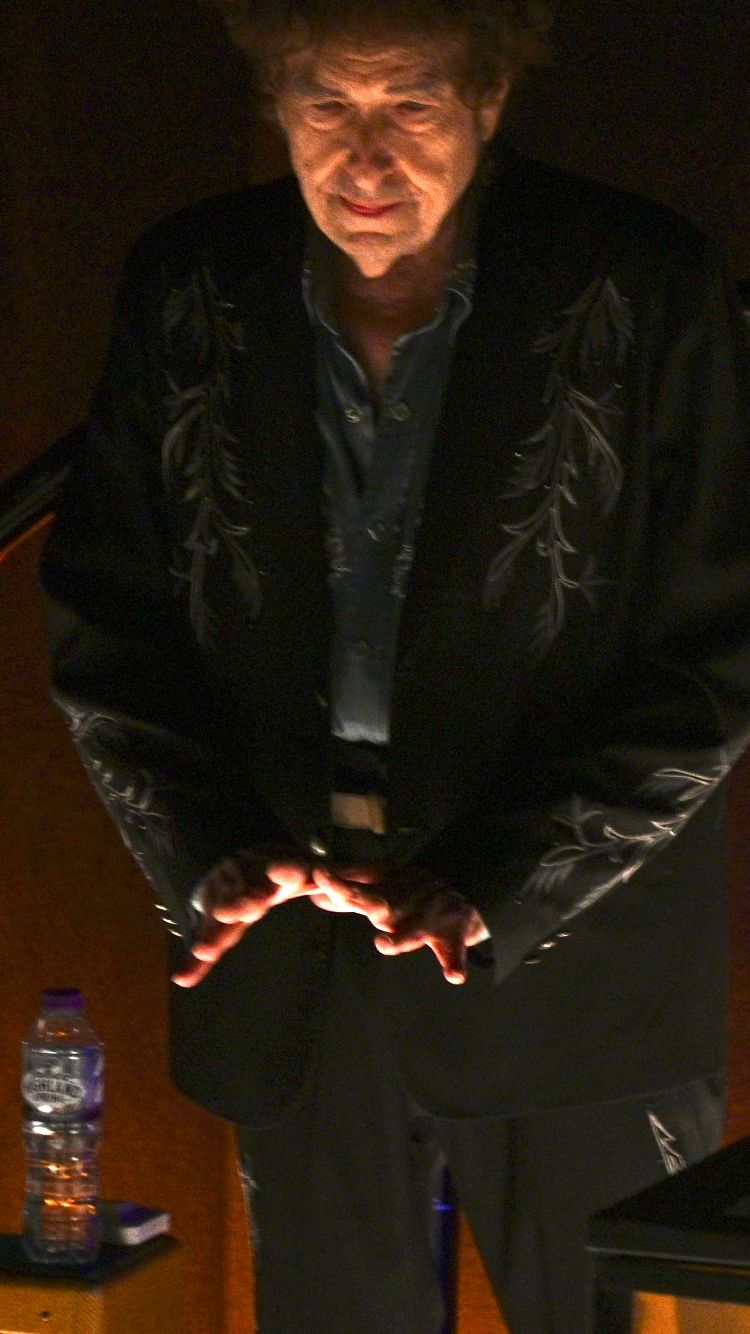

Bob Dylan, The London Palladium, October 23, 2022. Courtesy of and ©️ Andrea Orlandi,

Bob Dylan, The London Palladium, October 23, 2022. Courtesy of and ©️ Andrea Orlandi,Dylan and his almost indescribably symbiotic, and superb, band are concluding a tour of Europe most recently swinging through England and Scotland. I was at three of their four performances at the Palladium in London last month, having last heard Dylan and his band on the two nights in Denver, Colorado, when they finished the spring and summer leg of the tour.

Since Dylan began performing the Rough and Rowdy Ways songs in November 2021, the arrangements of every song on the almost constant set lists have changed dramatically – though, one feels sure, not permanently, as Dylan and the band try new things, shadings and contrasts and emphases, every single night. If you follow them and catch a suite of shows, you'll recognise the contrasts in the moment, as anyone who follows individual artists and bands on a tour, or attends a whole residency, well knows.

Dylan’s current band is composed of the longtime and elegant stalwart Tony Garnier on bass, multi-instrumentalist Donnie Herron, guitarists Bob Britt and Doug Lancio, and Charley Drayton on drums. This is a public plea for that band not to change any time soon. These men all get what Dylan wants to do musically and they’re doing it, with him and for him and the songs.

Song And Dance Man

The first night in London was October 19, but I missed that show, which was universally touted as triumphant in the local press and on social media. On the evening of October 20, the band was a man down: Bob Britt reportedly had to return to America for a prior engagement. Britt returned to raise the rock and roll levels of Sunday and Monday nights to a higher register. However, with just four instruments on stage, plus Dylan’s voice, all could be heard more clearly. This is not to say the sound was better; Britt’s contributions to every song are grand. Without the extra guitar, though, Dylan’s voice, Lancio’s guitar, and Herron’s grace-note contributions really stood out.

Advertisement

Garnier and Drayton are the jazz duo holding down stage right. In my dreams, they join Dylan, on his piano, in a trio one lazy summer weekend for their very own version of Live at the Village Vanguard. Drayton drums with his whole body, just like Levon Helm did, his hands propelling the feeling through wooden sticks, felted mallets, a whole painter’s boxful of brushes, and a cascaded handful of the lightest metallic necklaces over the cymbals in a sound that doesn’t sizzle but whispers and tickles and sighs.

Britt, long and tall like past Dylan guitarists Larry Campbell and Charlie Sexton (and he’s one himself, having contributed in the studio to 1997’s Time Out Of Mind), resumed his position on stage next to them Sunday night when he rejoined the band. Lancio stands almost behind Dylan and his piano, with Charlie Herron, surrounded by his whole panoply of instruments (pedal and lap steels, violin, mandolin) on a raised platform at stage left. The underlit floor makes Herron look as if he’s floating sometimes, and his delicate fiddle playing adds to this effect on certain songs.

The lights go down promptly for an 8pm start. As the applause begins, there’s a blast of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. It is from the first movement, after the quiet violin start, when the drum and then the whole orchestra come in. The well-known direction is allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso. Lively, but not too, a little majestic. That is Dylan as a performer on his stages these days, and the manner and sound of the Rough and Rowdy Ways tour itself.

Bob Dylan, The London Palladium, October 23, 2022. Courtesy of and ©️ Andrea Orlandi,

Bob Dylan, The London Palladium, October 23, 2022. Courtesy of and ©️ Andrea Orlandi,Dylan’s outfits are flash. Nudie – the man who coupled rhinestones and cowboys – might be gone, but long may his style reign. Dylan is clad in black cowboy suits with fancy stitching; his silk shirts shine in rich burgundy and green, loose at the throat; his boots tap time and carry him out from behind his piano as, with that light dancing step, he assumes center stage a few time, as the applause rains down. He no longer wears a hat. Dylan’s hats used to be part of his obscurity, huge and pulled low. Now the sturdy upright piano and its little dual lights like a butterfly’s antennae are enough.

Besides, as he sings in 'I Contain Multitudes', he likes to “fuss with [his] hair,” often pushing it back off his brow, flicking it away from his ears, and giving his head the occasional thinker’s scratch in between songs. His pose, standing at the keyboard, alters little. He rarely uses the pedals on the piano, trusting soft and loud and lingering sounds to his careful hands with their long fingers, flat splayed on the keys. Dylan often plays with only his right hand, resting the left on top of the piano, sometimes drumming lightly with a finger or two. His playing is not the honky-tonkin’ and saloon-rumble boogie-woogie of earlier tours. These days Dylan is playing the blues, and their sprightlier twin, jazz.

Advertisement

From the opener, 'Watching the River Flow' (1971), the whole sound of the tour quite simply wants to be heard. The instruments don’t drown each other, or elbow each other out of the way. One of the worst things about a Dylan show in years past has been the way his voice was too often obliterated by drums and bass turned up too loud in the mix. That problem is gone forever. It’s the voice, and the words he is singing, to which everything else is in support.

An interesting flip-flop has taken place in what audiences wants to hear as well. Sure, we love hearing the old songs, and on this tour Dylan serves up a generous selection from the whole sweep of his career to date: 'Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)' (1966), 'When I Paint My Masterpiece' (1971), 'I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight' (1967), “'o Be Alone With You' (1969), 'Gotta Serve Somebody' (1979), and 'Every Grain of Sand' (1981). He also tinkers significantly with the words to these well-known verses, particularly 'To Be Alone With You', which together with their new arrangements renders them fresh and fine.

However, the tour lets you know by its name that it is in support of the artist’s most recent studio album; if you go expecting he’ll pull out 'Like A Rolling Stone' or 'Blowin’ In the Wind', don’t complain when he doesn’t.

Dylan and his band perform every single song on Rough and Rowdy Ways but one, the nearly seventeen-minute monolith 'Murder Most Foul'. And audiences are loving the new songs. The applause and howls are generous: people around me knew the words and were singing along – or rather mouthing along, for they wanted to hear Dylan singing them. Though the Palladium is a sedate old palace with just over two thousand red velvet seats, I wish we’d been able to move more. The new arrangements aren’t nearly as danceable as in 2021, when people leapt up at the Anthem in Washington, DC to stomp to 'Goodbye Jimmy Reed' and 'False Prophet', and boogie to 'Gotta Serve Somebody'. But this music calls for physical sympathy in you. Expect to do a lot of seat swaying and, like Dylan, whose boots are just visible below his upright piano, foot tapping.

He really seems to be enjoying himself up there. When Dylan dropped the idiom “Everything’s gonna be doggone beautiful” into 'When I Paint My Masterpiece'. London loved it, and he did it again on succeeding nights. He chuckles aloud when he amuses himself with a line. Able to do what he likes, and knowing he’ll be supported flawlessly by the band, Dylan doesn’t spend a lot of time nodding and gesturing to his band members, cueing them and directing them.

They’re tight and watchful and professional and damn good. His bands have long reminded me of little Nipper in the old RCA Victor advertisements, listening alertly to “His Master’s Voice.” Now Dylan has a whole attending pack of expert individual musicians, all literally attuned to his arrangements on each and every song. There’s not a bum note or a low moment in their performances; everything really is doggone beautiful.

Advertisement

The phrasing on his new songs is Dylan’s greatest vocal strength. I’ve likened him to models and masters like Rudy Valleé and Frank Sinatra before, but The Philosophy of Modern Song sets me right in Dylan’s own words about Perry Como. When I was a kid, Como was the silver man who did wonderful Christmas specials on television. Everything about him was silver: his hair, his metal spectacles, his voice.

In 1978, he was in Williamsburg, Virginia, filming his special when a busload of school children passed by on their way back from a historical field trip, shrilling “We love you, Perreeeeeee!!!!” from the window. He waved to us all; I’ll never forget him standing on the steps of a reconstructed Colonial house, with a tall man behind him grinning and waving to us too – it was John Wayne, which we realised only as we were driving by.

My parents had his 45s and albums. 'Ave Maria' was one of my favourite songs, even though I didn’t understand a word of it yet. Reading Dylan’s words about Como made me realise why. “He is the anti-flavour of the week, anti-hot list and anti-bling. He was a Cadillac before the tail fins; a Colt .45, not a Glock; steak and potatoes, not California cuisine. Perry Como stands and delivers. No artifice, no forcing one syllable to spread itself thin across many notes. He can afford to be unassuming because he has what it takes. A man with lightning in his pocket doesn’t ever brag. He walks out onstage, cocks his head to better hear the band, stands in front of the audience and sings…and the people in front of him are transformed.”

Bob Dylan, The London Palladium, October 23, 2022. Courtesy of and ©️ Andrea Orlandi,

Bob Dylan, The London Palladium, October 23, 2022. Courtesy of and ©️ Andrea Orlandi,These words all apply to Dylan’s own live performances right now. 'Mother of Muses' swells and swoops, mesmerising, moving. 'Black Rider' smarts and stings, damning every corrupt politician who ever lived. 'I’ve Made Up My Mind To Give Myself To You' transforms the people in front, all right, who vocally and delightedly accept the gift every evening and give themselves in return. 'Crossing the Rubicon' and 'False Prophet', with their simple melodies and complex words, and 'Key West (Philosopher Pirate)' are the songs Dylan is singing best right now.

Every time I hear it, 'Key West' rises higher in my list of Dylan songs I couldn’t do without. Its grace and elegance is made so by the way he alternately withholds words while Herron plays or Drayton brushes the drums, and then delivers a line you will hear in your sleep for years to come:

Advertisement

“I’d like to help you but I can’t” and “Such is life, and such is happiness” and “I heard your news, I heard your last request.” 'Key West' remains particularly protean in the hands of its composer. On Sunday night in London, he repeated a line or two, less as if he’d gotten ahead of himself than as if he was sounding it out to see how it went in one place instead of another.

Only one song regularly on the set list is not by Dylan. 'Melancholy Mood', formerly the fourteenth song on the list, and the only one for which Dylan had moved to centre stage alone with his mic, got kicked to the curb that last night in Denver by a whirling, swirling 'That Old Black Magic', and has stayed gone on the European tour leg. Dylan stays behind his piano for this one. It gives him, I think, the opportunity to show his audiences a little more love, literally. How he drags out that final “loooooooove,” and my, the roar in reply.

The feeling I had at the end of all these shows was, first, happiness, and gratitude that I’d been there to hear them in person with all these kindred spirits, the men in the band, and Dylan. Then I tried to figure out what else it was. As is often the case when doing this in terms of Dylan and his art, his own words are one’s best help.

Writing in his new book about Dean Martin’s version of 'Blue Moon', a song he says has “traveled through time and crossed every cultural abyss,” Dylan reflects: “Some songs, like ‘Yes! We Have No Bananas', ‘When I’m Sixty-Four', ‘North to Alaska', and ‘Free Man in Paris’ are as dependent on their arrangements as the music or lyrics for their identity. Not so ‘Blue Moon'. ‘Blue Moon’ is a universal song that can appeal to anybody at any time.” What gives this ballad its flexibility and universality? The “dignity that is within this melodic ballad.”

Dignity. Dylan once wrote a whole song on the theme, where it is and how you find it; his drafts, in the Bob Dylan Archive in Tulsa, Oklahoma, show that he worked on and revised ‘Dignity' more extensively than any other I can recall. Dignity. Not just the grace, and phrasing, and excellence of Dylan’s current band as well as his own piano playing – for which he has never gotten proper credit from all the guitar lovers – but the dignity of his new songs are driving this tour.

Bob Dylan, The London Palladium, October 23, 2022. Courtesy of and ©️ Andrea Orlandi,

Bob Dylan, The London Palladium, October 23, 2022. Courtesy of and ©️ Andrea Orlandi,Advertisement

Dignity is responsible for the happy and overwhelmed audiences, the five-star reviews, the sold-out theatres and halls. You walk out into the night feeling that some of it has rubbed off on you. You might not even know that that’s what it is, but it feels wondrous, magical.

You’ve witnessed something stately and unique, and you stand a little taller as you walk through the sudden downpour on Regent Street, humming in the rain, proud that you were there to not only bear witness, but to join together. That’s something far more than entertainment.

Follow me close, I’m going to Ballinalee.

Bob Dylan and his band arrive in Ireland this coming weekend for just one show, on Monday night, November 7, in Dublin at the 3Arena. The Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour is meant to conclude in 2024. Where will Dylan and the band go, after a Thanksgiving, Christmas, Hanukkah, and New Year’s break? Likely somewhere in the southern sun, if past tour patterns hold true. He’s regularly toured in the American South, Australia, and occasionally Japan in the early spring, and then likes to go on to Europe, or sometimes the northeastern United States and Canada.

In my many hundred times of hearing Dylan with very varied bands over four decades, this current tour, from its personnel to the songs being played, are above us all – on some other artistic, emotional and cosmic plane entirely. The newspapers are right: something is happening here that you really don’t dare miss.

Please go. You’ll be so glad you did.