- Culture

- 13 Jun 20

The intrigue around a new Bob Dylan record is unparalleled. “I don’t think there are any new souls on earth. Caesar, Alexander, Nebuchadnezzar, Baal, Nimrod,” Bob said in July 1983. “they’ve all been here time and time again.” Could he possibly have had an album called Rough and Rowdy Ways, to be released in 2020, in mind?

Rough and Rowdy Ways (Columbia, June 19) is the first album of new songs by Bob Dylan since Tempest (2012). The first two tracks — 'I Contain Multitudes' and 'False Prophet' — and the last — 'Murder Most Foul' — were released this past spring, and have already been much discussed. From them one could have guessed not at the extent, but at least at the depth, and rich generosity, the whole record would show. The concept “I contain multitudes” is surely borne out by these circling, crafted, often unsettling, sometimes gentle, and generally testamentary songs.

Bob Dylan has seen and done more than most of us have, will, or could in 79 years. As you listen to this double album, though, with its long stanzas and sweeping, looping, often lush but never excessive musical arrangements, 79 is just a number, and you have, indeed, no sense of time. When long ago Dylan wrote that line, “I have no sense of time,” it seems to me that he sang of a sense of time like Hamlet’s or William Butler Yeats’s: circular, instead of linear.

All history, and its people, fictional or real, walk together in the same time as Bob. That’s a huge part of Dylan’s power as a songwriter: the past isn’t past, history; and the art and literature created within it, aren’t dead or even static. It all still lives for him, and he re-animates it for us. This is the force and achievement of Rough and Rowdy Ways, and in this action there is care, and something like affection, or maybe even love.

That re-animation drives ‘My Own Version of You’, in a creepily literal way. Many a singer-songwriter will tell you, if pressed hard or caught in a vulnerable moment, that their songs are written to themselves. As potential addressees fight over who the “she” or “you” is in a famous tune, a songwriter smiles, knowing that it’s self-reflection. In ‘My Own Version of You’, the singer comes at you from the position of Victor Frankenstein — and, perhaps, ‘The Creature’ too.

“All through the summers into January

I been visiting morgues and monasteries

Lookin’ for the necessary body parts

Limbs and livers and brains and hearts

Ah, bring someone to life is what I wanna do

I wanna create my own version of you."

Advertisement

The loved one as scientific experiment is a longtime artistic standard. Mary Shelley, only eighteen when she began writing Frankenstein one night in the summer of 1816 at Lord Byron’s challenge, set another standard: that of the Romantic reconstruction of life, reason, and love from death, and the Gothic horror accompanying this project. Dylan crosses time and genre in this frisson-filled track, the first line of Richard III adapted to begin one stanza, and a terrifying filmic mash-up to begin another:

“I take the Scarface Pacino and the Godfather Brando

Mix ‘em up in a tank and get a robot commando

If I do it up right and put the head on straight

I’ll be saved by the creature that I create.”

Dylan’s shifting, elliptic pronouns always make you sit up and take notice. When he shifts from “he” to “I” in performances of ‘Tangled Up In Blue’, you have to wonder: who’s singing to whom? What he told Scott Cohen in 1985 seems to me the best assessment of the powerful, Romantic I, from whose point of view the songs on Rough and Rowdy Ways are sung.

“Sometimes the ‘you’ in my songs is me talking to me. Other times I can be talking to somebody else. If I’m talking to me in a song, I’m not going to drop everything and say, ‘Alright, now I’m talking to you’. It’s up to you to figure out who’s who. A lot of times it’s ‘you’ talking to ‘you’. The ‘I,’ like in ‘I and I', also changes. It could be I, or it could be the ‘I’ who created me. And also, it could be another person who’s saying ‘I’. When I say ‘I’ right now, I don’t know who I’m talking about.”

The “someone” Dylan wants to bring to life, turning back the years, might just be himself.

Sure, Rough and Rowdy Ways is elegiac, though don’t think for a moment it’s Dylan elegising himself. ‘Black Rider’ is a stinging elegy, with swords and fire and profane dismissal: “My heart is at rest, I’d like to keep it that way / I don’t wanna fight, at least not today.”

‘Goodbye Jimmy Reed’ is a romping, glorious, boogying hello, more than it is a fare thee well. ‘Mother of Muses’ is an elegy to history and the lineations too many see drawn within it. Dylan knows his classical epics and lyrics as well as he knows his Shakespeare; after invoking Mnemosyne, though not by name, he tells her what to sing for him. It’s epic he wants — he’s not just falling in love with Calliope; he’s been in love with her for a long time — and indeed the singer takes over the epic prerogative from the muse himself, just as Homer and Virgil do.

Advertisement

“Sing of Sherman, Montgomery, and Scott,

And of Zhukov, and Patton, and the battles they fought,

Who cleared the path for Presley to sing,

Who carved the path for Martin Luther King

Who did what they did and they went on their way

Man, I could tell their stories all day.”

This is a good time to note the sound of the whole album, as rich and deep and varied as the lyrics. From the stately, quiet grace of ‘Mother of Muses’ to the swinging beat of the aforementioned ‘Goodbye Jimmy Reed’ to the swoony backup singers on ‘I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself To You’, who are the other musicians on this album? Is it all Dylan’s traveling band? Or are those Jim Keltner’s sweet snarey drums on ‘Goodbye Jimmy Reed’? Are those Fiona Apple’s delicate keyboards? Rumours abound. Only the official release will tell any and all personnel.

The one-two punch of ‘Crossing the Rubicon’ and ‘Key West (Philosopher Pirate)' is my favourite section of Rough and Rowdy Ways. Were the record an epic poem construction, I’d say these are my favourite books. Both are long songs, telling stories, giving and taking, promising and threatening, cautionary and yet comforting.

‘Crossing the Rubicon’ is an old-style gutbucket shuffle, with more sass and twang than blues, ominous, incontrovertible as its title action. When Gaius Julius Caesar, conqueror of Gaul, disobeyed the Roman Senate’s orders in 49 BC, and with one of his legions crossed that red river in northern Italy, he began a civil war that ended Rome’s republican days and began imperial Rome. To cross the Rubicon is to do something that cannot be undone. Don’t look back: it’s a concept Dylan has embraced before, but never in such a literarily, historically, lyrically layered song. Really, who else would yoke “paint your wagon” to Dante’s Inferno? Its lines, marching long as any epic’s and as intricately rhymed, are downright multitudinous.

"I crossed the Rubicon on the fourteenth day

of the most dangerous month of the year

At the worst time, at the worst place,

that’s all I seem to hear

I got up early so I could greet the Goddess of the Dawn

I painted my wagon 'Abandon all Hope'

and I crossed the Rubicon."

That insistent 'I' gains in power throughout the song, until both the spiritual and natural world join in, instead of menacing or thwarting any more:

"The killin’ frost is on the ground and autumn leaves are gone

I lit the torch, I looked at the east, and I crossed the Rubicon."

Advertisement

‘Key West (Philosopher Pirate)’ begins with the assassination of William McKinley, and mentions Harry Truman’s ‘Little White House’ on Front Street in Key West. A lead-in to the concluding song on Rough and Rowdy Ways, ‘Murder Most Foul’, which centres on the assassination of John F. Kennedy, is thus here, but ‘Key West (Philosopher Pirate)’ is very much about other things.

I finished listening to it for the first time, and thought, this is an album of love songs. They’re as complex and distressing and elevating and beautiful as love is, and ‘Key West (Philosopher Pirate)’ is what I’d take to the desert island, were I allowed just one. I’ll bear witness, Bob, if you’ll be my mutineer. This gorgeous song is sung by Odysseus on an isle that’s a cross between Ogygia and Aiaia, where contentment and peace coincide with frightful magics, and the skull beneath the skin.

On the sun-kissed sandy shore, the singer fiddles with a little manmade box and its thin aerial, “Searchin’ for love, for inspiration/ On that pirate radio station,” down in the boondocks, down in the bottom, down in the Keys.

“Key West is the place to be

If you’re lookin’ for immortality

Key West is paradise divine.

Key West is fine and fair,

If you’ve lost your mind

You’ll find it there.

Key West is on

The horizon line.”

On June 19 – a day when so many of us remain rightly cautious and full of care, masked and gloved and self-isolated to the extent that we can be while getting on with work and life – go strand yourself for a couple of hours with these travelers’ traveling songs. Be shipwrecked. Get lost. Happily you don’t have to choose just one song for your desert island, and don’t spend too much time parsing the lyrics and picking them apart: the meaning is in the whole.

I’ve long thought of Dylan’s songs as mosaics. High Modern Romantic that he is, painter and sculptor that he also is, Dylan writes mosaic songs, collage songs, pointillistic songs, composed of bright gems and fragments and splinters, but best seen and heard in the altogether, if you will.

Advertisement

Rough and Rowdy Ways is a present, a gift of rhyming couplets in lyric patterns, deceptively simple instrumentals that are perfectly turned by immensely skilled unknown hands, and Dylan’s voice right in the register where it should be. New songs from him always make you think; this time, they also make you feel.

Rough and Rowdy Ways is a record we need right now, and it will endure. Like someone once said of a kindred spirit of his, Dylan’s not of an age, but for all time.

• Keep an eye out for Pat Carty's verdict on a record that may yet divide opinion.

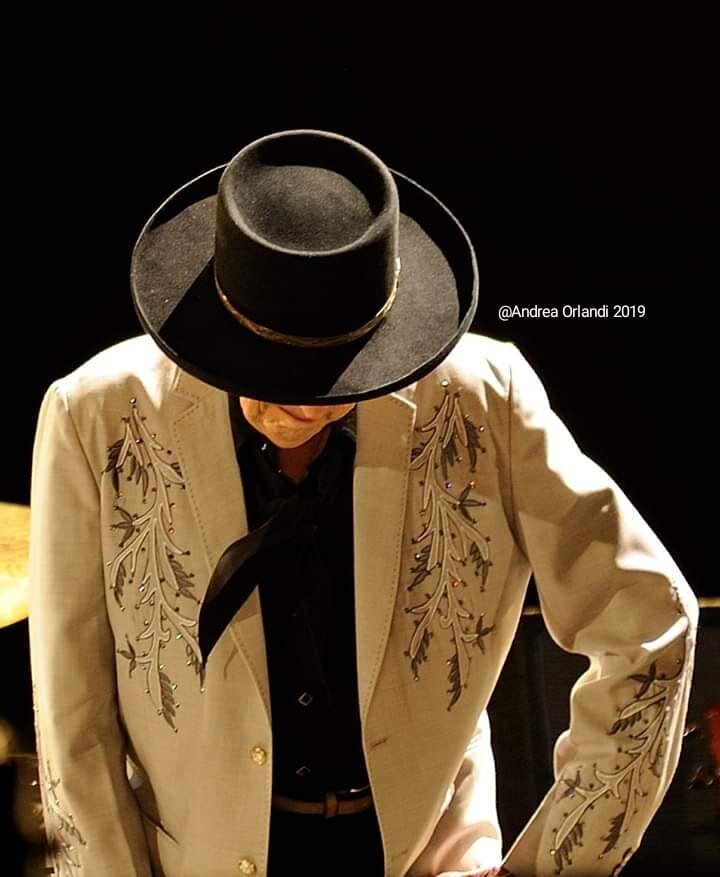

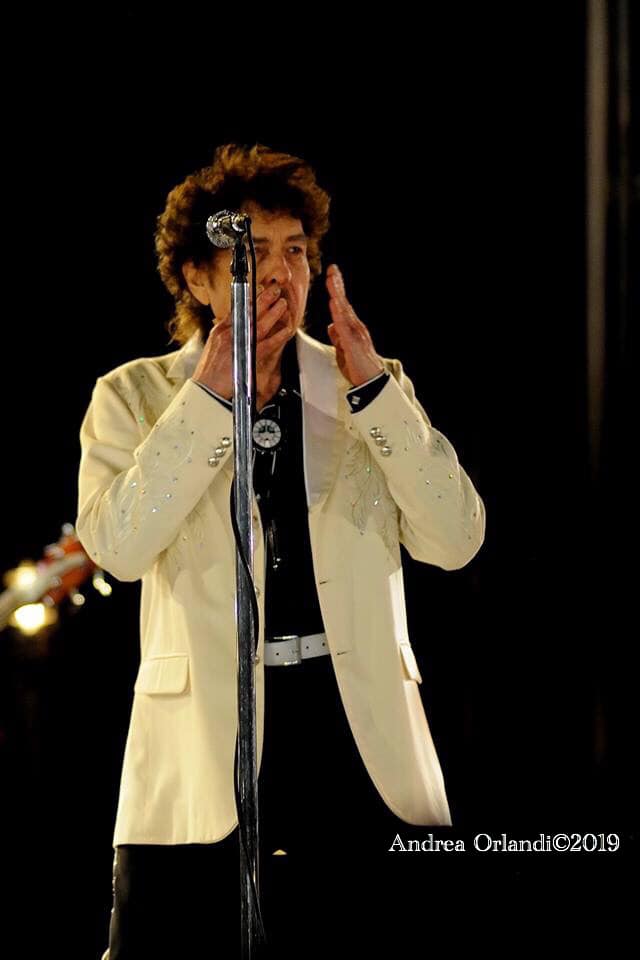

Pics courtesy of and © Andrea Orlandi