- Culture

- 19 Feb 19

The Visual Arts in Ireland 2019: An interview with the RHA's Mick O'Dea

The lifeblood of a city is always found in its arts and culture. Art enriches our lives and holds up a mirror to society. It allows us to see ourselves as we are. It connects us to our history, and in many ways, builds a bridge towards our future. And it also attracts visitors to these shores.

Thankfully, the visual arts scene in Ireland is alive and thriving. From painting and sculpture to film and digital media, the world of the visual arts is more intersectional than ever before. This multifaceted use of materials in many ways reflects how varied and frenetic the modern pace of life has become. But it also comments on just how adaptable we humans are. In an age of widespread highlight reels, it allows us to stop and slow down, as and to engage with our emotions in a meaningful, and often therapeutic, way.

In Ireland, we’ve always been particularly good at making the best of what is in front of us, and at drawing on our rich heritage and history. Right now, artists across Ireland are working with diverse materials and methods to create exciting works that comment – frequently in a challenging wayy – on contemporary life. From portrait painters to sculptors, commercial galleries to museums, the visual arts continue to excite and inspire.

From painting live portraits to serving as president of the Royal Hibernian Academy, Mick O’Dea is one of Ireland’s most prominent artists. Mick believes very strongly in our collective need for the visual arts. Irish people have a fascination with processes and seeing things in the making. Casting his mind back to his brother’s pub in Ennis, Mick O’Dea recalls one of the most formative experiences of his early career.

“I was painting a customer at the bar and he was staying very still,” he recalls. “We had agreed as long as he sat, he could have as many pints as he wanted. Soon the pub was packed. There seemed to be a sense of excitement. I finished the painting, put down the brush and said, ‘I’m finished’. Everyone in the pub burst into spontaneous applause. That was the first time I ever experienced the thrill musicians must get when they play live.”

In certain ways, the role of the painter is similar to the musician. Both use pattern, rhythm, balance and emphasis to elicit a response from their audience. Did Mick experience the same nerves musicians can be prey to? “I actually enjoy it quite a bit,” he laughs. “I find that I get a thrill out of it and it makes me want to show off. I enjoy the danger that it could all go horribly wrong. It keeps me on my toes when I’m in that type of scenario.”

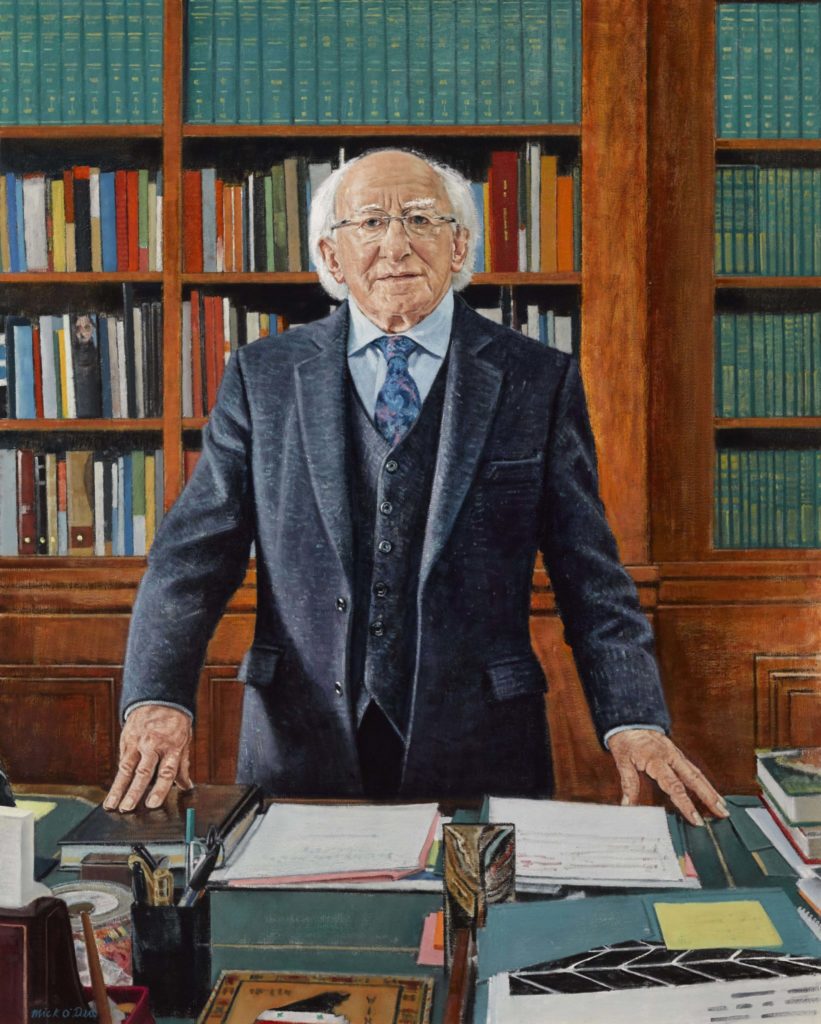

President Michael D. Higgins, painted by Mick ODea

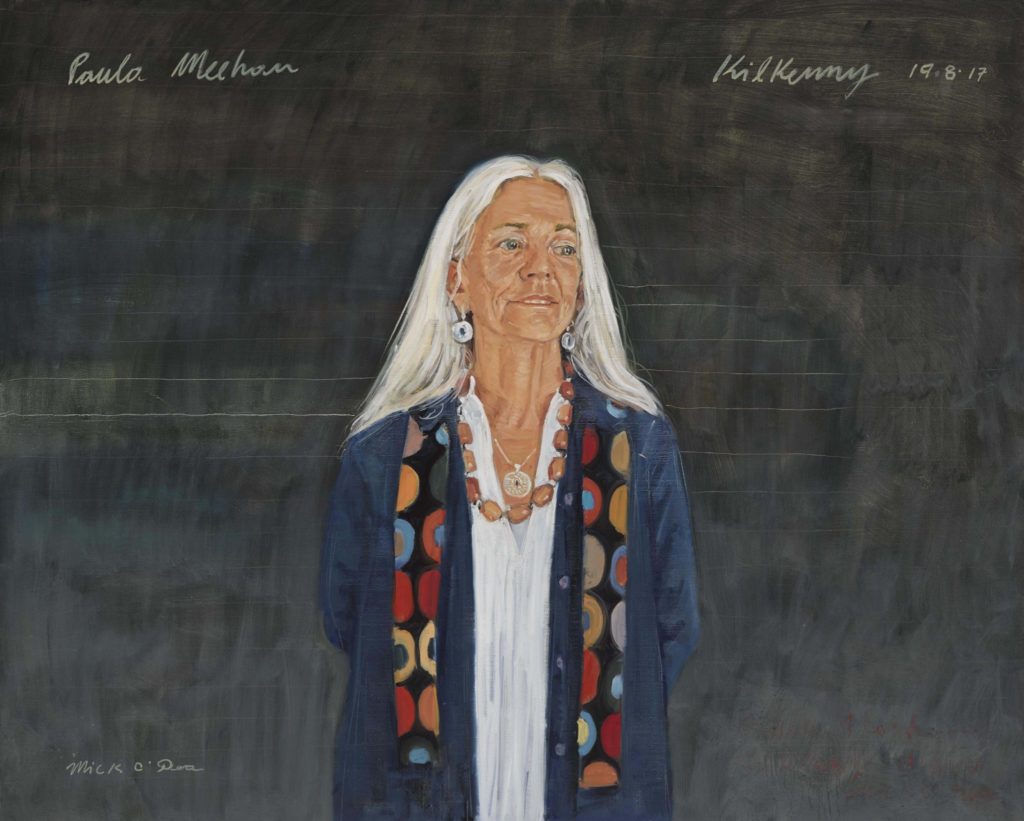

President Michael D. Higgins, painted by Mick ODeaAmong his many accomplishments, Mick spent three seasons as the artist-in-residence at the Kilkenny Arts Festival, painting portraits before a live audience. There, he created works depicting some of our finest musicans, literary figures and actors, including Colm Tóibín, Paula Meehan, Paul Muldoon and Stephen Rea, whilst giving the public a rare chance to see an artist live at work. In today’s society of flux and impermeable boundaries, live painting seems almost like a calling.

“The role of the artist has never really changed,” says Mick. “It’s just to get on with their own work. Each artist has a responsibility to identify their own voice and pursue that; every artist is involved in the world and an observer of the world. Their observations are the reality of being there, which will enable them to distill their experience of being in the world and reflect that back.”

During his four years as President of the Royal Hibernian Academy, Mick has been instrumental in laying the foundations for the future of the arts in Ireland: he established the Charter Sub-Committee, which began the process of the Charter Amendments, preparing the RHA for the next 200 years. He also established the RCSI Art award and strengthened the ties between the RHA and other academies, in addition to championing a younger generation of Academicians.

“Humanity’s achievements are always measured in their cultural legacy,” he reflects. “Each generation has an obligation to leave a cultural inheritance. It’s very hard to separate one from the other. Our art really is a human activity, and the art made by any culture or society reflects the values of that society. Let’s hope there is a future for humanity, and that art will continue to play a vital role in that.”

While the core purpose of art may remain the same, some things do change. The rise of technology, social media and instant connection has impacted on the art world as much as other creative industries, if not more.

“I think people have abandoned representational painting as a vehicle for telling stories and given that over to film,” Mick posits. “A lot of representational painters will paint a portrait or a scene, urban landscape, and there may be some story element. But many times there aren’t. But we’re far more visually sophisticated today. The understanding of images today is probably similar what obtained in the medieval period.

Paula Meehan, by Mick ODea

Paula Meehan, by Mick ODea“The people in the Middle Ages really worked on images and rituals. If you were an illiterate peasant in medieval Europe and you went into a cathedral to look at a stained glass window, you understood the story: it unfolded in front of you. I think we’ve caught up with medieval Europe in terms of our ability to read and understand images.”

Of course, this comes with advantages and disadvantages.

“There’s a lot more image manipulation, whether it’s for advertising or art,” Mick explains. “Visual art is very dependent on materialism. Irish traditional music flourished because they were able to harness the creativity of the people, in spite of the poverty. But it was no coincidence the Renaissance occurred in Florence when it did. Florence at that time had the population Limerick has today. The difference was that it was the capital of the baking world. Money and visual art are entirely tied up.

“Irish banks in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s led the surge, in terms of buying art, but now they’ve jettisoned their collections. What we need are more private companies putting money back into visual arts and encouraging artists for the greater good. The government needs to continue supporting and expanding their range of activities, but I think it’s really important they spend the money on organisations that already have the expertise, and are already up and running.”

Though factors like technology and the economic downturn have all had an impact on art, and its practice within Ireland and abroad, there will always be a desire for art. The form may change, the way we experience it may differ, but the human need to create is ever-present. As a renowned painter of portraits, historical subjects and landscapes, for an artist like Mick the function of art is to reflect the world we live in.

“I think art is essentially about bringing people face-to-face with what’s real,” he says. “I don’t think it’s about escapism or downtime. Reality can give you down time – whether listening to silence or birdsong – but art is a mirror to society and the world. Art is about being real.”

For more information, go to http://www.rhagallery.ie/

RELATED

RELATED

- Culture

- 04 Sep 25

Exhibition of photos by asylum seekers in Ireland to open in Wexford

- Culture

- 30 Jul 25

Hugh Lane Gallery to close for "at least three years" for refurbishment

- Culture

- 21 Jul 25