- Culture

- 03 Mar 22

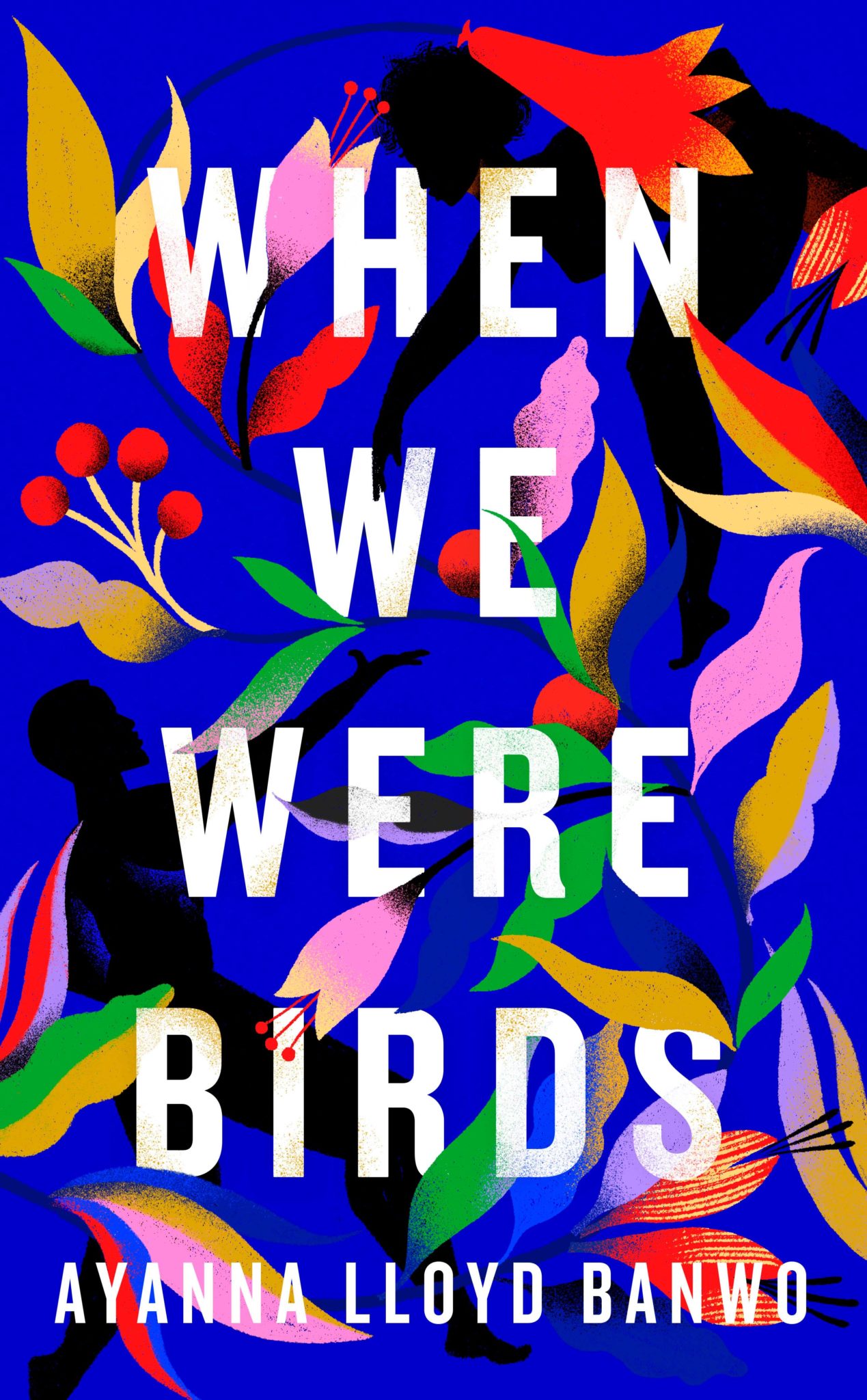

When We Were Birds author Ayanna Lloyd Banwo: "“My grandmother told stories like breathing. For her, anything could be a tale”

Trinidadian author Ayanna Lloyd Banwo discusses her superb debut novel When We Were Birds, which explores death and grief to powerful effect.

Ayanna Lloyd Banwo officially moved to London from Norwich in March last year to live with her now-husband. It felt familiar to her, having visited many times from Trinidad. Though her current surroundings are the hustle and bustle of densely populated English cities, debut novel When We Were Birds takes place in Ayanna’s colourful homeland, blending the richness of myth with contemporary life.

The plot focuses on Darwin, a gravedigger newly arrived in Port Angeles. Estranged from his mother since breaking his Rastafari vow, he is convinced that the father he never met may be waiting for him in the city.

Meanwhile, Yejide’s mother Petronella is dying. She leaves behind a legacy that now passes to her daughter: the power to talk to the dead. Darwin and Yejide’s destinies are heavily intertwined, and they’re set to find one another in the ancient Fidelis cemetery.

The vibrancy of Trinidad is contrasted with the seemingly dark setting.

“I spent a lot of time in cemeteries from 2013 onwards,” the notably warm Ayanna tells me over Zoom from London. “We had a lot of deaths in my family in a short space of time, which meant that I was consistently interacting with death from all angles. Everything from finding the grave people to the paperwork was tricky, because nobody in my family had died for quite some time. Then it all came in a rush.

“I wasn’t in Trinidad when the first death happened, which was my mother. She was the kind of gangsta who didn’t have an ID card or passport (laughs). They needed to identify her, and my family asked me to send a picture of myself from South Africa because we had the same face. It didn’t work, obviously!”

Around 2017, the Trinidadian put pen to paper to write a short story, focusing on a man who grew up Rastafarian before abandoning his faith to become a gravedigger. Having applied to the University of East Anglia, it was the first story Ayanna workshopped, later growing into her literary debut.

“I’m very interested in looking at my history from years before, because I grew up in a family of storytellers,” she notes. “My grandmother told stories like breathing. For her, anything could be a tale. There were about seven or eight grandchildren, and we’d go to her house in the afternoon when the parents were at work, and she’d entertain us. Within her words, there was this sense that we didn’t come from just anywhere.

“Many people without wealth find their own personal history by going to graveyards. The process of grieving is intensely spiritual. I spent a lot of time, particularly with my mother’s death, wanting to dream of her. Wanting to feel like there was a message that was going to be delivered to me. She died unexpectedly. There was no long illness that gave us time to prepare. Her death was an apocalypse for me.

“The paperwork of death is so intense. Each memory and item has a resonance. Irish and Caribbean wakes are similar, where there can be joy and laughter, but there is a sense that this person is hovering over you. I’m interested in how we mourn in different ways. My crafting of Darwin is based specifically on the Nazarite vow. There’s this iconic image of Rastafari worldwide as being somebody who lives closer to nature, honours a code, and in a way resists the world. Someone who shuns the ungodly, the unnatural, the unjust. The trope is one of quiet defiance. It doesn’t mean all Rastafarian people don’t go to funerals.”

There was another aspect which fascinated her.

“For me, graves are portals, documents, archives,” she adds. “All Souls Day is big in Trinidad, similarly to how Irish pagans celebrated Samhain. The kind of death that colonialism brings to you is unique. Our cultures indigenously would have approached it in a natural way beforehand, but the rupture of families is a different kind of loss. Maybe Trindad and Ireland think about grieving a lot culturally, because we walk on the bones of those lost to imperialism, violence and conflict.”

In a nod to the author’s upbringing, When We Were Birds opens with a mythological tale told to Yejide by her grandmother Catherine, recounting how her female ancestors came to embody death, through the medium of corbeaux birds after tropical storms.

“Trinidad is a melting pot of all kinds of different races,” says Ayanna. “The Native Amerindian population are the bedrock of Caribbean stories, but we sort of forget that they were here first (laughs). The story that opens the novel is inspired by Indigenous Amerindian creation tales, which often feature some cataclysm that transforms a place of Eden to a different world with the intervention of human beings. That’s how I allied the industrialisation of war and people with the introduction of death.”

Why did Ayanna choose to write the male partners of the ‘Morne Marie’ women as living in service to these powerful agents of death?

“That might be because I was being so incredibly well-partnered by my husband when I was writing this book!” she beams. “My writing process takes place in manic bursts. I spend a long time mulling in the back of my mind, and then I could be four or five days in a fever dream of writing. In those times, somebody needs to cook, clean and do laundry. That’s something that, historically, the wives of writers did. It allowed them to be prolific. Service becomes a very gendered thing in that way.

“For me, domestic life is necessary. Partnership of whatever kind is necessary. Somebody has to take out the bins and make sure the kids are picked up. Someone needs to tell you that you’re worn that shirt for five days straight (laughs). We’ve just consigned that role to women. My own life circumstances made me think a lot about service and the importance of the domestic space for any kind of work. The Morne Marie women can’t oversee death unless they’re supported in many ways.”

As well as flipping stereotypical gender roles, Ayanna made sure the presence of queerness was felt within the bond between Yejide and her best friend Seema.

“It’s important to acknowledge that these women are living a very cloistered life that’s separate from other people,” she says. “In the way that Darwin’s faith has made himself and his mother outsiders, Yejide and her mother are also outsiders. They find community in each other. It’s not rare or strange for young girls to experiment sexually, or for deep, meaningful female friendships to become intimate.

“Sometimes those relationships become partnerships, but sometimes it’s just part of a sexual awakening. It can just be an intimate part of friendship. I wanted there to be a sense that they are outside of the labelled dimension of sexual orientation. This is love, sex, sharing, partnership, service; but it’s also complicated.

“Trinidad is not tolerant of those kinds of relationships in terms of the legal framework. It was only quite recently that homosexuality was decriminalised. However, there have been queer people on the island since the beginning of time. I can’t speak on behalf of the whole community, but queer people have always been here, whether or not the State or your fellow country people decide you are worthy or not. It doesn’t negate the fact that you exist.”

This supports the dominant message behind the book, the knowledge that love possesses a seismic ability to honour those who aren’t with us anymore.

“I wanted to bring this sense that we have ancestors to attend to,” says Ayanna. “We have people who have been lost to us in all sorts of ways that we have to help: bones and history to care for. That was what deeply motivated me to craft this book. Considering I was in love, I don’t know why it didn’t occur to me that it would also be a love story!”

• When We Were Birds is out now, published by Penguin.

RELATED

- Culture

- 16 Jan 26

TradFest South Dublin 2026 launched at Tallaght Stadium

- Opinion

- 16 Jan 26

Irish humanitarian Seán Binder acquitted on all charges

- Culture

- 15 Jan 26

The Complex announces official closure

RELATED

- Culture

- 12 Jan 26

The Divine Comedy pay tribute to David Bowie with 'Starman' cover

- Culture

- 12 Jan 26