- Film And TV

- 20 Dec 21

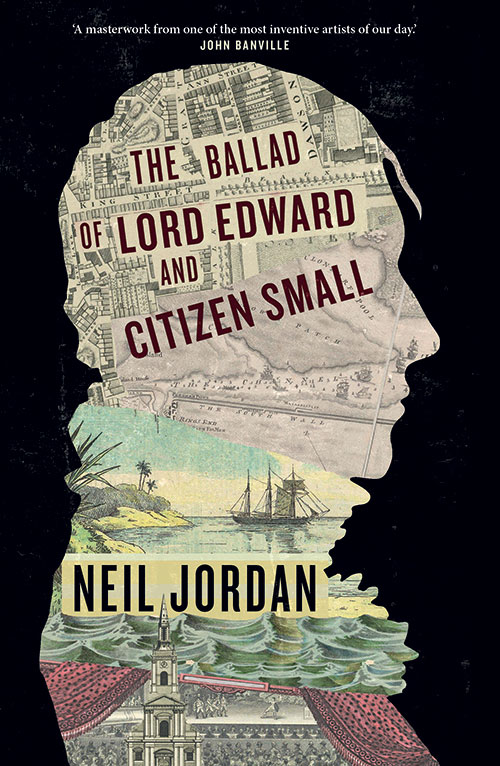

12 INTERVIEWS OF XMAS: Neil Jordan – On The Ballad of Lord Edward and Citizen Small

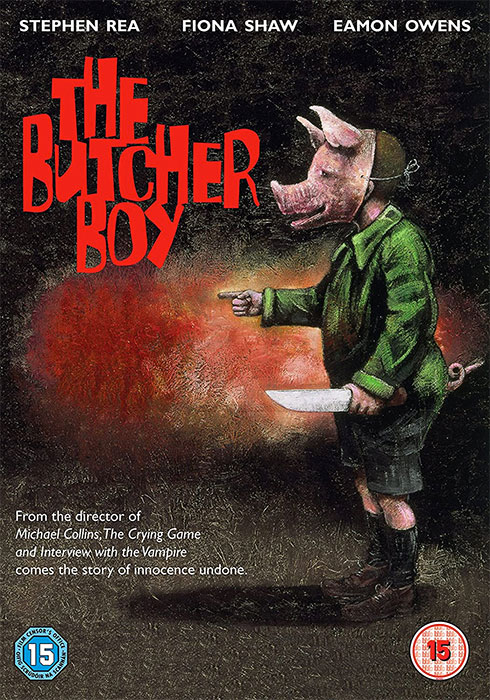

As part of our 12 Interviews of Xmas series, we're looking back at some of our unmissable interviews of 2021. Rightly lauded as the director behind such celluloid gold as The Crying Game, Michael Collins, and The Butcher Boy, Neil Jordan is also one of Ireland’s greatest, if ever-so-slightly unsung, novelists, a fact proven again by his latest work, The Ballad Of Lord Edward And Citizen Small. “I just like making up things,” he told Pat Carty in February.

Before we proceed, I must ask you to sit back for a quick history lesson. I don’t offer this in a talking-down kind of way, but out of necessity. It’s a long time since I was an undergraduate so I had to take a bit of a refresher course myself. Lord Edward Fitzgerald is a complex figure. Born lucky as the sixth son of the Duke Of Leinster in 1763, he had it all handed to him and then he handed it all back in the name of Irish freedom, taking up with The Society Of United Irishmen, and taking part in the 1798 rebellion, or rather he would have had informants not led to his capture the night before it all kicked off.

The life of this fascinating character is the focus of Neil Jordan’s The Ballad Of Lord Edward And Citizen Small, although it is Tony Small who tells the tale, or sings the ballad, if you will. Small was a runaway slave who came across the badly injured Fitzgerald after the Battle Of Eutaw Springs in the American Revolutionary War and nursed him back to health. In return, Fitzgerald freed Small with a letter from the King and employed him as his manservant until the end. Jordan’s excellent novel relates their various adventures – through America, Europe, Britain, and Ireland - from Small’s point of view.

Before we get started, it should also be noted that Mr Jordan stopped on many occasions to ask - not in any kind of condescending way either, but because this is a complicated subject - if I understood what he was talking about, which took me right back to my school days, where I would have heard tell of Fitzgerald in the first place.

Another Perspective

I began by asking what had attracted him to the story of Fitzgerald and Small, the first time he has used a true story in his writing, although Mr Jordan did point me in the direction of a small movie he had made called Michael Collins by way of correction.

“I read some of the biographies some years ago, and the mention of this chap, Tony Small, and his relationship with Lord Edward Fitzgerald came out, and I began to think about it and write some things down,” Jordan remembers. “Hodges Figgis, on their 100th anniversary, asked for contributions from Irish writers, so I published a little bit of it then, and then put it aside. I just wasn't sure of it because of all of the issues of cultural appropriation, but the story just fascinated me. There's so much you can research about Lord Edward’s life, and so little you can research about Tony Small. I wouldn't dare try to write an account of this man's life, particularly in his own voice, but I thought if he writes his account of Lord Edward, it would be interesting.”

Given the dearth of research material available relating specifically to Small, constructing the narrative using Lord Edward’s voice might have been an easier option, but there are reasons why Jordan chose not to.

“Because I needed another perspective on the hallowed ground of these Irish affairs,” is how he explains it. “Not many people know or think about the 1798 period. When I told people I was writing this book, they’d say, ‘it's about who? Lord Edward Who?’ So for me to take the perspective of this person, who would have known nothing about the Irish experience and the Irish relationship with the British Empire and all that, was really fascinating. You wouldn't call it a contemporary perspective, but it's kind of like a tabula rasa, an uncluttered perspective on Irish events by somebody who knows nothing about them.”

The Mystery

There’s a point in the book where Lord Edward states he has common cause with the runaway slave, the common croppy and the press ganged seaman, but he didn’t, at all really. He had everything, by birth, and he gave it all up.

“That's the mystery, and it's something that none of the biographers can explain,” Jordan agrees. “Thomas Moore – Moore’s Irish Melodies and all that - wrote a two-volume biography – actually a three-volume biography - about Lord Edward Fitzgerald in the 19th century. He had some acquaintance with him, and he used huge, extensive accounts, from his letters and from the letters of the family, and it still didn't give any clue as to why this man made such a huge leap of allegiance. There was a biography by Stella Tillyard [Citizen Lord: Edward Fitzgerald 1763-1798] which is very, very good, but it still doesn't explain it.”

“You can understand Wolfe Tone, you can understand Robert Emmet, one can see the journey that these other figures took, and a lot of them are political theorists themselves, but with regard to Lord Edward, it's very hard to comprehend how this man became so radicalised. He was influenced by all of the revolutionary kind of ideas at the time - the French Revolution was happening - but for somebody who fought loyally against the American Patriots in the American War of Independence, and was an army officer for so long, to then became so suddenly radicalised, it's a great conundrum.”

Is there something to the notion that had Fitzgerald become the Duke Of Leinster himself, if he had been the eldest son, things would have been different?

“Perhaps, there's so many mysteries. Was it that he was a younger son, whose only options were the either the church or the military? Was it that he was rejected so many times by the lovers that he chose? Was it his experience in America when he went back there with Tony Small, although he was an officer then? He takes this journey down to New Orleans and out of it comes this increasingly radicalised figure. I thought it'd be really interesting to look at that experience from Tony’s perspective, somebody who had nothing. The idea of giving away all this inheritance would be an absurdity, really, and I suppose in a strange way, the idea of resistance to the Empire, to the insane mad King [George III] who gave Tony his letter of freedom would seem equally troubling or questionable. I thought it was a really interesting perspective from which to view Lord Edward’s journey.”

There’s the three women - Lady Catherine and Georgiana and Elizabeth Sheridan – who broke Edward’s heart. Did this pain, if you'll allow me, lead him into the arms of Thomas Paine, the American political activist and Rights Of Man author, whose influence he fell under in Paris? Was there a hole in Fitzgerald that needed to be filled?

“Yeah. Was he a hero, or was he fool? That's the basic question.”

Tony Small says at one point, “I met a fool in the forest”, which he later amends to “I met a hero in the forest”. Jordan reckons he was right both times.

“He was a bit of both really, but you have to understand that the whole experience of the United Irishmen. It was essentially a Protestant movement. It came out of a radicalised Belfast and spread down into the south, where the Catholic peasantry were very unwilling to embrace it, because they were dominated by their clergy, so it's a really complicated period, and a really tragic story. I thought of Tony Small as Lord Edward’s tutor, in a strange way. His experience of freedom, the fact that he grabbed it and took it, was this a kind of tutorial that led Lord Edward to his basic choices.”

A Series Of Tragedies

Would the United Irishmen have seen Lord Edward as a great prize to be won over?

“A huge prize. He was a Geraldine, and he had military experience, the experience of organisation that a Lieutenant would have had. There’s a puzzle to the journey, that's one of the reasons why I wanted to have Tony Small narrate it, and question it himself.”

Jordan has pointed out that 1798 is not as discussed or read about as much anymore – “Well, it’s forgotten, really,” he says – but could it have gone differently? What if, for example, the French forces that Wolfe Tone accompanied towards Bantry Bay in 1796 had been able to land through the storms?

“It is the series of tragedies about Irish Rebellion, isn’t it? I'm down in Bantry Bay,” Jordan says, pointing out his window, “and if the French had made it up there and hadn’t been blown to shreds... Also, the entire experience of the United Irishmen in Dublin was so riddled with informers. If you read the accounts of the information that was coming in to Dublin Castle at the time, they give a far more detailed account of the entire Dublin experience then you would get from a regular history. It's almost as if the castle knew everything that these individuals were doing.”

So was the endeavour doomed before it even started?

“Well, they had a good plan. They were going to burn the mail coaches, and the fact that coaches didn’t arrive in different areas of the country was going to lead to a popular revolt. And the popular revolt, when it did come, much later, was incredibly savage. There were so many missed opportunities, and so much bloodshed and so much tragedy, really, but I suppose it could have succeeded.”

The history books say that the centenary of the rising in 1798 was part of the impetus for the revolt in 1916. Is that its legacy?

“1798 was a far more interesting movement than the later republican movement,” Jordan reckons. “It straddled all classes, straddled various religions, and the intellectual logic for it was far more interesting. They were basically following the example of the French Revolution and, I suppose, the American Revolution of 1776. Figures like Henry Joy McCracken, and Samuel Neilson, and all those Belfast United Irishmen and revolutionaries were very, very interesting men, and there was this extraordinary figure of Olaudah Equiano who, like Tony, was a freed slave and who wrote one of the first slave narratives. He lived with Neilson in Belfast for about four or five months, so it was a very interesting period, in many ways much more interesting than Pearse and MacDonagh, which was kind of a Catholic movement really, and led the state that we all had to suffer. The period of the United Irishman was far more open to possibilities.”

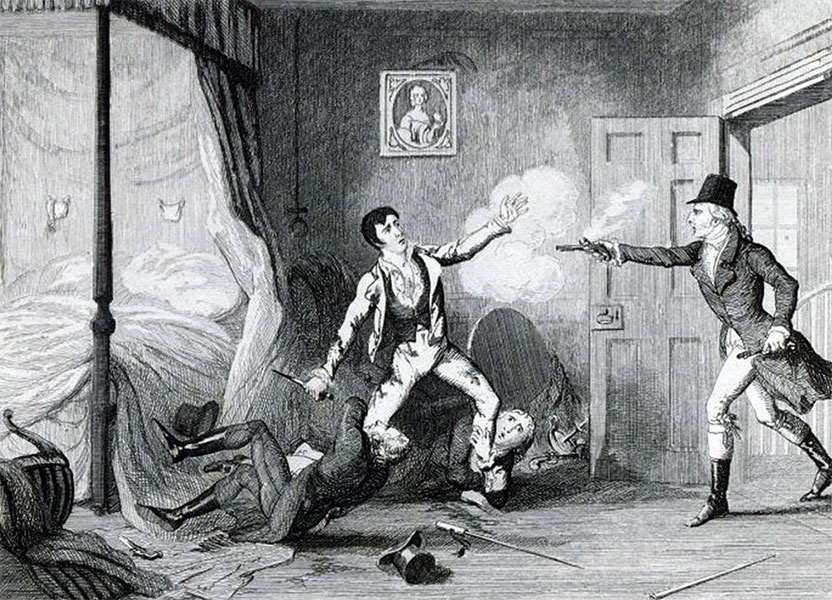

The Arrest Of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, George Cruikshank

The Arrest Of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, George Cruikshank

Grounds For Invention

When Tony Small first comes across Lord Edward, wounded after the Battle Of Eutaw Springs, his first inclination is to rob him, but instead he nurses him back to some semblance of health, offering the reader an indication of his decent character.

“He should have killed him, shouldn’t he?" Jordan asks. "He may as well have stripped that corpse clean and run, but, for some reason, he doesn’t. That's my perception. The way I structured it, it is almost like fate intervenes, that he allows him to live, and after that they're stuck together, as companions, as friends, as master and servant, and sometimes a bit more of one then a bit more of the other.”

Lord Edward has to put Tony in his place on occasion, for appearances sake if nothing else.

“It’s a relationship that began in amity, in friendship, and a kind of mutual support, but as they enter the world of Ireland and England the master/servant paradigm of the relationship reestablishes itself without Fitzgerald perhaps being aware of it, so they drift apart, and they come together, and they drift apart. And Tony has to tug the forelock in the various houses in England and Ireland, It was an interesting opportunity to examine the dynamics of a relationship like that.”

Lord Edward rewards Tony Small with those papers of freedom from the King which Tony carries with him in an oil skin. Jordan offers some historical context behind this.

“There's a book by Simon Schama, the historian. I forget the name of it now [At a guess, Mr Jordan is taking about The American Future: A History]. The big paradox of the American War of Independence is the fact that it left slavery intact, which is horrendous and one of the reasons that I thought it'd be interesting to write this novel. 'The peculiar institution', as they call it, dominates the conversation about race in America, even to this day. In the middle of what you might call the Patriot Rebellion, the promise of freedom was made to any runaway slave who joined the King's Regiments, it ran through the south like wildfire, and it being the British Empire, all of those promises were successively broken. A lot of them ended up in Nova Scotia, and the entire history of the Sierra Leone in Africa was kind of an attempt to make good on those promises, but they weren't followed through in any real sense whatsoever, and that was a separate tragedy of its own."

"From my perspective, the idea that Tony had been given this promise from the King of England, that made him as free as Lord Edward FitzGerald himself, would have been so important to him that he would have kept this paper with him all the time."

But, in reality, it was scarcely worth the paper it was printed on?

“It wasn't worth the paper it was printed on, and as Lord Edward says in the end, nobody gave Tony his freedom, he took it himself, and that's the basic thesis of the book, really. He didn't even need the King of England to give it to him, It was his to take, and my supposition is that this was most basic lesson that Lord Edward learned from the relationship."

Jordan was right to ask me if I understood, as it's only at this point that it really dawned on me what he was attempting to do with his novel. He was offering an imagined reason behind Fitzgerald's volte-face, one that was missing from the biographies he mentioned earlier, the notion that Tony Small's influence on Lord Edward may have been a factor in his decision to step across the aisle.

Lord Edward Fitzgerald

Lord Edward FitzgeraldMore Irish Than The Irish Themselves

When they arrive in the old world from the new, Small's first experience of England is from the top of a carriage. He sees the country as a kind of paradise, although he eventually concludes that it hides its paradise well.

"I think he would have gotten the perception that England was a paradise lost," says Jordan. "England can be terribly beautiful, particularly those tiny little towns with the church peeking through the trees. It tends to hide its beauties very well, England, doesn't it? Particularly at the moment. I think Tony was seeing something that could have been perfect, but actually wouldn't be. I didn't want to write an anti-English story, I wanted to write a story about the complexities of rebellion against Empire, about the tension between civilisation and its opposite, which is chaos. There is something to be said for civilisation in the end. There is something to be said for order and rules.”

From England they travel to Ireland, although not before Small is warned that it is an island of savages. Jordan paints a picture of extremes, with poverty and luxury side by side, as they make their way through the streets of Dublin.

"If you think of Leinster House, Dáil Éireann, and parts of the National Museum, and parts of the National Library - that was one family home. That was one of the reasons I wanted to write the book from Tony's perspective, because you can imagine these grand, quite beautiful constructs, sitting on this medieval pit, basically. It must have been extraordinary and quite a horrific place at the same time.”

In the course of his research, Jordan made a connection with another recognisable name from Irish history.

“As I was exploring all these extraordinary things, I didn't realise that Silken Thomas himself was one of the great, great, great grandfathers of the Fitzgeralds. I didn't realise he was from the same family. You're thought your history at school, you always learn about this figure Silken Thomas, don't you?"

The best I could offer in response at the time was to say that I remembered the name, but I can tell you now that Silken Thomas was, technically, the 10th Earl of Kildare, who was executed in 1537 for leading a rebellion against his cousin, Henry VIII.

"He was a Fitzgerald himself," Jordan continues. "The Fitzgeralds did represent those who became more Irish than the Irish themselves, these large families that had a genuine allegiance to the country they lived in.”

At Carton House - the family estate near Maynooth - Edward's older brother, The Duke Of Leinster, says of Silken Thomas that he forgot that he served at the pleasure of the king, which is what his brother would go on to do.

“Absolutely. The Duke would have been much older than Edward himself, almost old enough to seem like his father, and from his point of view, that would be a big, big mistake, and I think he would take that to heart in a way, this revolt against everything that gave him all of these privileges that he had.”

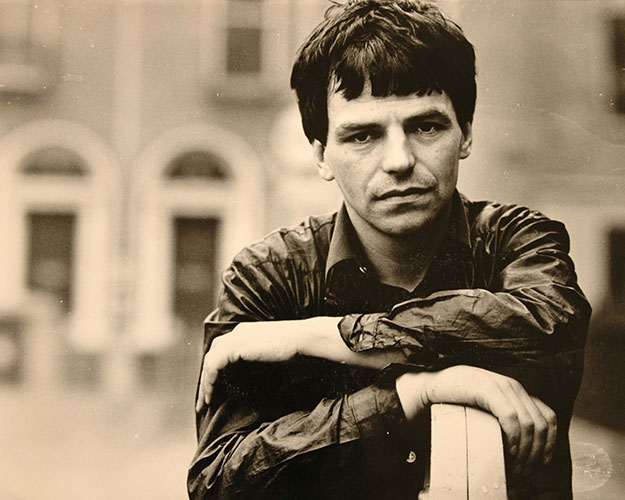

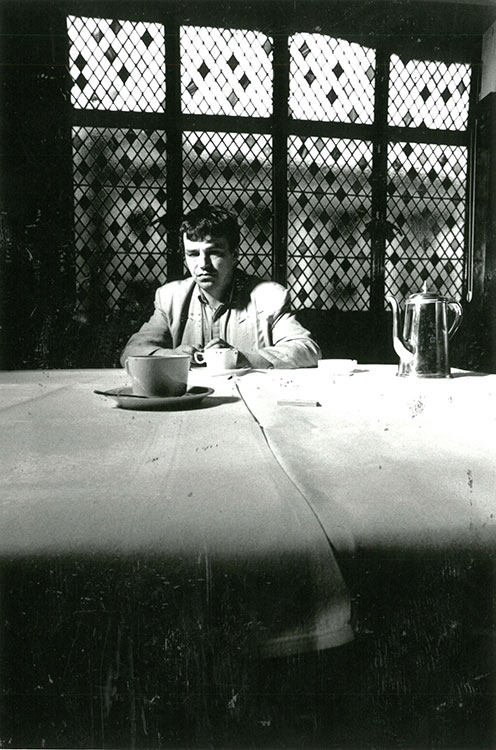

Neil Jordan, as shot by Colm Henry

Neil Jordan, as shot by Colm Henry

Continue The Research

Jordan very obviously undertook extensive research in order to tell the story, and base his suppositions around his imagined life of Tony Small.

“If you do your research as thoroughly as you possibly can, it gives you grounds for invention. After having done Michael Collins and being accused of abusing Irish history, to the extent that some people said I did, which I didn't think myself I was doing, really, I just thought I was making a movie, I wanted everything that I was relating about the Fitzgerald story and the story of the United Irishman, and the story of Dublin at the time, to be as exact as I could possibly make it.”

"It is extraordinary what you can discover about the web of informers, from the United Irishman themselves and from ordinary people in the street, who knew the figures involved. The communication was all through letters, and you can read those letters. The powers that be in the in Dublin Castle knew more about the population that were rebelling against them then the populace knew themselves.”

Wasn't Edward warned that those in power knew what he was up to and what was going to happen?

“They did warn his family, because they were part of the same class. They did want to get him out of the country, because they didn't want events to come to the pass where they would have to execute him like a common criminal. They did give him that option, that is part of the history. I have Tony Small bring the letter, what I would call in inverted commas the letter of freedom, with the offer to leave the country and go to the United States and live as a private citizen. That offer was made.”

There's another offer of American relocation in the novel when Thomas Paine recommends that Louis XVI be sent to America, where every man is king. Tony knows that this is not necessarily true.

“Tony knows that's not the case, doesn't he? He knows that every man is king only if they're a white free man. If they're an enslaved African, they're not a king at all. That's one of the paradoxes of the great story of American Independence that people are only beginning to explore it. And it doesn't need me to point out that fact."

Jordan reiterates why he decided to recount the period through Tony Small's eyes.

“I just thought it was a far more interesting that it was not from an Irish perspective. Even if it had been Henry Joy McCracken or Napper Tandy telling it, it still wouldn't have been as interesting to me as this perspective. I felt it would give an opportunity for the narrator to question the entire logic of the drive towards independence. It's a big question for Irish people, isn't it? I don't think it will ever go away either.”

Brexit and lockdown and everything that’s happening might, possibly, be edging us closer to… something…

“I think it is possible. I find it very strange at the moment, because the first time I published a book [Jordan’s short story collection, Night In Tunisia, initially published in 1976] the first award I got was from England, The Guardian Fiction Prize. When I first began to make movies, they were financed by Channel Four and by the British film industry, and that relationship between the Irish arts and the British arts is incredibly important, particularly in terms of the theatre. Every Irish playwright depends on the London theatre for real recognition. The cross fertilisation between both cultures has always been immense and it seems to have stopped now in some strange way. I'm surprised at how disturbing I find it myself, but that's the story of Brexit, and that's a different story!”

The Jordan section of the Carty library

The Jordan section of the Carty libraryMultidisciplinarian

In her review of Jordan’s novel Mistaken, “when faced with fiction writing as fine as this,” the late Eileen Battersby asked, “why does Neil Jordan bother making movies at all?” Bearing in mind that it was his writing that got him into movie-making in the first place – John Boorman hired him to work on Excalibur (1981) with IMDB listing him as “creative associate”, Jordan directed The Making Of Excalibur: Myth Into Movie documentary, and then Boorman produced Jordan’s debut feature, 1982’s Angel – does he now have a preference between the two disciplines?

“I don't have a preference, I just like the activity of making up things, and I love making movies as much as I like writing books. Writing books is a far lonelier pursuit. I've always felt that at some stage, I won’t be able to make movies anymore, so I’ll just go back to writing novels, But the reason I think Eileen was wrong is that I don't think I'm a natural novelist, in fact, I'm not sure I know what a novelist is?”

Someone who writes novels, I offer.

“I know, but what's a novel? What does The Great Gatsby have in common with War And Peace? One is about one-hundred-and-ten pages, the other two thousand pages.”

Never mind the quality, feel the width?

“I know,” says Jordan, graciously stepping over my misplaced attempt at wit. “But it's a big, baggy, unwieldy form. The reason I always liked cinema was because the story was so precise, in a way. The stories would begin at minute one, and they'd end around minute ninety. The only equivalent to the Victorian novel now is the endless television series, like The Sopranos if you're lucky, or if you're unlucky, like something else that just goes on forever and keeps repeating itself. At least with the movie, it's an experience that you get to have in one sitting.”

You could read The Great Gatsby in one sitting, I point out.

“Absolutely. You can read The Great Gatsby in one sitting, you can read The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter in one sitting, but you couldn't read Bleak House in one sitting.”

It would certainly be a long sitting, if one were to attempt such a thing. Does he not then have more creative control with a novel?

“I think you've got an enormous amount of control in films, really,” he counters. “It's a totally different thing. It's a different media, a different part of your brain. I don't see why people shouldn't tell stories; explore themselves in two or three different forms. A lot of painters deal in sculpture; a lot of painters now deal in video art. I don't see why I shouldn't keep making films.”

I wasn’t implying for a second that he should not, but is it not a much more difficult thing to bring to fruition?

“It is a difficult thing to bring to fruition. That's true. You’ve got to deal with finances, actors, you got to do all that sort of stuff. And then you got to deal with critics. It's a different experience, believe me; if you release a movie, you get responses from all over the bloody universe. If you release a book, you get a review in The Irish Times, maybe The Guardian, maybe The Independent, and that seems to be it.”

And Hot Press, of course. Jordan continues.

“The great thing about movies, too, is that they’re often based on other pieces of work. I made a movie called The End Of The Affair, based on a very thin book by Graham Greene, one of the most beautiful books ever written. So I can make a version of that thing. When I made The Butcher Boy, it was kind of tearing apart Pat McCabe's novel and putting it back together in something like a recognisable form. You don't have that opportunity when you're writing, unless you rewrite The Butcher Boy and publish it as another novel. I can make work based on other pieces of work, which is great fun.”

I Can’t Go On. I’ll Go On.

The rights to his 2016 novel, The Drowned Detective, were bought by Amazon, and Jordan was reported to be working on its adaptation, but it never appeared.

“They didn't want to make it,” he says, matter-of-factly, before expanding on what happened. “It's more simple than that, actually. I began writing the script and they were reading it and said ‘ Oh, well, why don't you do this? Why don't you do that?’ I tried the ‘why don't you do this’ kind of approach. And eventually I said, ‘Look, this is nothing like the book I wrote’. I wrote a script that was loyal to what I'd written, and we parted ways, and that happens a lot in movies. I still have the screenplay, I still will make that movie.”

You will or you would?

“I will. Yes, I will,” he states, Joyceanly.

That’ll be the first time he has adapted his own work. Is this something he has deliberately avoided?

“No, that was a strange cross-fertilization, because actually, I began writing a screenplay with the story of The Drowned Detective, and then I thought, ‘why don't I try writing this as a novel?’ Oh, I know what happened. I began writing a screenplay that would become The Drowned Detective, and then I was whacked by a bus on Dawson Street and I couldn't actually move for two years, so I wrote it as a novel, because, at the time, I couldn't walk and I thought, maybe I'll never be able to make films again.”

I offer the opinion that there’s a good movie, or mini-series at least, in The Ballad Of Lord Edward And Citizen Small. Jordan thinks it might be too big and complicated for a movie, but a series might be an option.

“I would happily develop a TV series based on this, but I would work with other directors. I'd work with some African-American directors or Afro-English directors. I'd work with directors who would be able to bring out certain aspects of it, and I'm thinking of doing that, actually.”

Loath as I am to mention the war, I ask if Jordan would be wary of working in television again, given that The Borgias was cancelled before the story was completely told, and he publicly disowned his other small screen creation, Riviera, after the episodes he wrote “were changed, to my huge surprise and considerable upset,” as he was quoted as saying at the time.

“The Borgias was fun. It was a big success, actually,” he says now.

Okay, but what about ‘the other one’?

“The other one, Yes. It’s a bit confusing,” he says, with a hint of a smile. “No, that was a unique situation, it wouldn't happen again that way. With The Borgias, DreamWorks had commissioned me to write a screenplay about it, but they thought it was too expensive so they didn't want to make it. Steven Spielberg said, ‘Why don't you try turning it into one of these TV series?’ When I began to do it, all the material expanded. You do all this research, and I loved doing that.”

Is that a better way to approach that kind of story then, with extra room?

“I think sometimes it is, if there's huge complexity to the background material, you're often better off letting it expand into something longer than a feature film. I think television does suit that kind of material very well.”

Marvel & The Middle Tier

Given all that has happened in the last year and the continued success of the streaming services, has movie making changed now, and is it harder to get a movie made?

“What you call the consuming of movies has changed utterly but the making of it has not changed that much and, if you're willing to make them with the streaming service, not at all. If you look at what Netflix and Amazon are doing, they're making tons of movies - not all of them good - but they are the kind of movies that the studios had totally abandoned.”

Something like The Dig, which I saw the other day?

“The Dig, or…”

The Irishman?

“The Irishman? Perhaps, all the studios had turned that down. The great tragedy of the five studios is that they were making these huge tent pole films like the Marvel movies, and blah, blah, blah and blah, blah, blah, and they weren't making the mid-range, small budget movies at all, they were being made by independents. The streamers, whatever you say about them, and you can say they’re destroying the act of going to the cinema, but they're not destroying cinema, they are supporting it in a strange way.”

How about the physical process of making movies now? Is it not nearly impossible at the moment?

“Yeah, I'm so glad I haven't made a movie. I'm particularly glad I’m not waiting for a film to come out, because all the cinemas are closed. I don't know how people do it with the COVID restrictions. They are doing it though, and I hope to make a movie in September, which I can't talk about at the moment. I'm hoping that we’ll be able to walk around streets with cameras on our shoulders and have people bumping into one another again.”

We don't even need a movie. I just want that to come back anyway.

“Yes, I just want to bump into people!”

That middle tier of movies that you said the studios aren’t making, is that where you feel most comfortable?

“That's where I exist. I've never made a Marvel movie. I’ve never made a Disney fairy tale, though I'd love to, but they wouldn't let me I'm sure. I've never been commissioned to do the Disney version of Snow White.

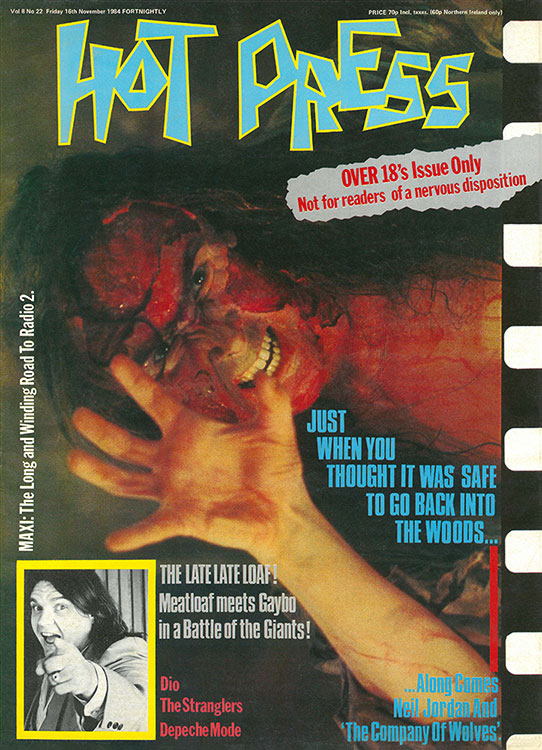

You already had the wolves…

“I understand that. It costs too much I mean, the biggest movie I've ever made was Interview With The Vampire.”

Lestat and Louis had capes.

“But they weren't caped crusaders, although maybe they should have been flying. You connect me with movies like Mona Lisa, The Company Of Wolves, The Crying Game, and Michael Collins. They're not superhero tales, they're not tent poles, they're not movies that you'd release all over the world on the same day, and that’s what they were looking for. But that's what the streamers are kind of supporting, at the moment. They're making a lot of bad movies, but they're supporting a lot of alternative voices, a lot of black directors, a lot of female directors, a lot of gender fluid directors and others. In fact, that's the name of the game these days.”

Did you enjoy any of those tent pole movies, those caped crusader movies?

“I really enjoyed Guardians of the Galaxy. I enjoy some of the extravagant mythological storytelling, but I don't get why Robert Downey Jr. wants to wear a metal suit and fly around the bloody planet. I just don't understand it. Let's put it that way.”

I rub my fingers together in the internationally recognised symbol for cash, which raises another smile from Jordan before I ask him what he would do if they came to him in the morning with a blank cheque, and told him to go off and make the next Iron Man movie.

“I'd write it first,” he insists. “I think they've been quite clever, the people of the Marvel Universe, because they've hired directors who perhaps have made one or two small movies that have shown at Sundance or something, and they've thrown them into these huge machines, and they realise that the executives can control the story in a way, so they kind of want neophyte directors. Another one I did love actually was Black Panther. I thought of myself at fourteen, seeing that in a cinema.”

Jordan has not seen Thor: Ragnarok, directed by Taika Waititi. I mention that genuinely oddball romp as proof that sometimes art and commerce can meet in a good place.

“Oh, absolutely,” he agrees. “They’ve been very clever, because sometimes these new directors bring great instincts with them, and they bring great irreverence to this kind of material, but you have to realise, a lot of these films use a thing called Previz, do you know what that is?”

I confess that I do not.

“Okay. It's a whole set of computerised technologies where you pre visualise the movie before you actually make it,” he explains. “And with that tool, people can say, ‘Oh, we like that. But we don't like that. We'd like that. We don't like that’, before they actually come to shoot the movie, often because the digital elements and the kind of special effects elements are so complicated.”

Is that not, in some way, the same as Jordan storyboarding a film?

“It's more complicated. On the one hand, it's very expensive, and on the other hand, you have to present it to the producers and studio.”

Would he not have to do that anyway, on a smaller scale?

“No, I've not had to do that.”

Jordan in 1991. Pic: Leo Regan.

This Writing Life

Jordan tells me that this book has been finished for a few years so I’m legally required to ask what he has been doing during the lockdown.

“I've written several scripts, I've been working on a few things. And I'm waiting to find out which of them will happen first, really. And I'm writing a really short novel; it may even be a short story. But I hope it will reach the 100 or so pages you need to put it out.”

Size doesn’t matter, it’s the telling of the story that is the important thing.

“It is, in a way. I'm having a lot of fun writing at the moment. Glad I can do it.”

Lockdown is surely akin to a writer’s normal working life anyway.

“The truth is, I've always worked from home. I've never been to an office party in my life. I may go at some stage, just to see people photographing each other's bums on the photocopy machine. Even when you're making movies, you’re always working from home.”

It’s been said, by wiser heads than mine, that lockdown and the epidemic have proven just how important art is to our lives.

“I would hope so,” is Jordan’s take. “Of course I think the arts are terribly important. You don't want your life to be dominated by NPHET or whatever it's called. You can't even pronounce it. How do you pronounce that? There’s all these horrible words around these days into like ‘Brexit’ and ‘NPHET’. At least we can make better words out of these things, if they left it up to people like us.”

They could be the names of characters in Jordan’s Marvel movie, if they’re ever smart enough to ask him to make one.

The Ballad Of Lord Edward And Citizen Small is published by The Lilliput Press

Read more of the 12 Interviews of Xmas here.

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 29 Dec 24

12 INTERVIEWS OF XMAS: Paul Mescal - "Fear can be very motivating"

- Film And TV

- 02 Jan 23

12 INTERVIEWS OF XMAS: Lisa McGee On The Unforgettable Final Season of Derry Girls

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 01 Jan 26