- Film And TV

- 08 Jan 25

A Complete Unknown: "Timothée Chalamet gets closer to being Dylan than the man himself sometimes does"

With the hotly anticipated biopic A Complete Unknown – in which Timothée Chalamet gives a bravura lead performance – about to arrive, Jackie Hayden considers Bob Dylan’s singular impact on the history of music and pop culture.

With Bob Dylan being one of the most distinctive and iconic figures in music history, portraying the singer is a serious challenge for any actor. But in the magnificent new biopic, A Complete Unknown, Timothée Chalamet – the Hollywood superstar celebrated for his roles in the Dune movies and Call Me By Your Name – plays Dylan with an uncanny level of accuracy.

Indeed, the actor gets closer to being Dylan than the man himself sometimes does. Given The Big Zim’s famously unique vocal style, Chalamet has achieved the nigh-on impossible, singing and portraying him with such conviction, that actor and “real-life” character merge convincingly. We’ve had countless Dylan impersonators down the decades – some inspired and others less so – so the actor’s work is a triumph worth celebrating.

Some commentators see Dylan himself as constantly playing a part. It’s as if he’s always remained Robert Zimmerman, using Bob Dylan as a grab-all name for the different masks he wears, and a cover for the many contradictions encountered by those following his trajectory.

Over the years, Dylan’s musical creations have swarmed with characters, lots of them real, many fictitious – and some who might be both real and fictitious. Among those characters is Dylan himself, something he acknowledged in the title of the comparatively recent song ‘I Contain Multitudes’. It’s worth remembering him remarking to a Halloween night audience in New York, as far back as 1964, “I have my Bob Dylan mask on”.

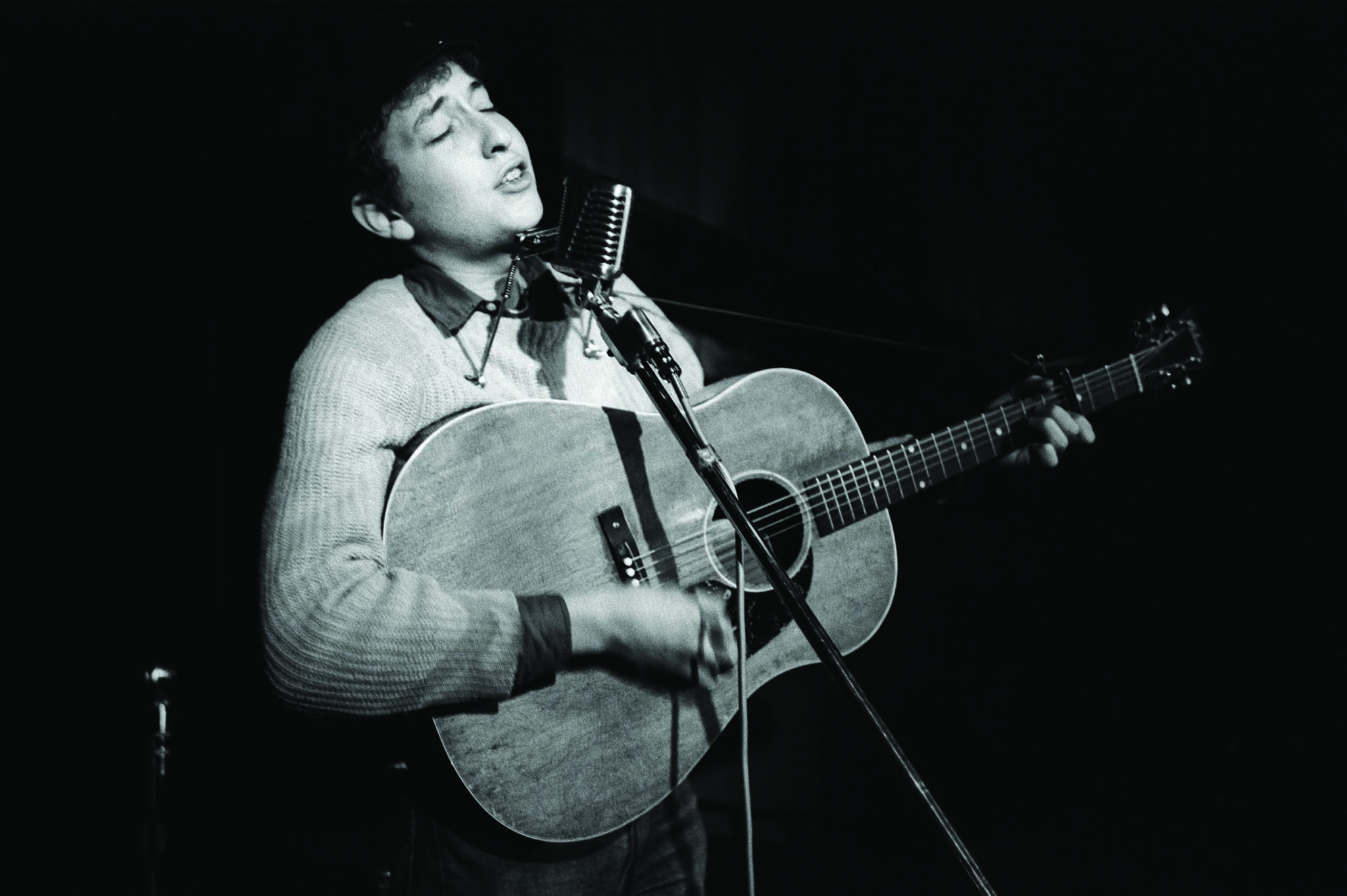

Bob Dylan, on stage at Gerde's Folk City, NYC, 1961. Credit: Ted Russell

In DA Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back rockumentary, meanwhile, he mocks, “God, I’m glad I’m not me!” after reading stuff about himself in a newspaper. When director Sam Shepard asked Dylan if he ever felt like a couple, he replied, “Yeah. All the time. Sometimes I feel like ten couples.”

Never totally reliable regarding his work or his life, or anything much really, Dylan has unhelpfully claimed, “I am not a playwright. The people in my songs are all me.” He has also said that when he used words like “he”, “it” and “they”, and talked about other people, he was really talking about himself.

So how do you portray a man who seems to permanently exists somewhere between fact and fantasy? From the beginning, Dylan has invented and reinvented his multitudes of selves, telling early interviewers his parents were dead; that he had left home to work in the circus and travel the country; and other amusing fibs.

The job of portraying a man who Liam Clancy described as a shape-shifter is a mighty task. In his portrayal of the self-styled “song and dance man”, it was a conundrum Chalamet bravely had to solve, by becoming as close to Dylan the performer as anyone might. As the film’s producer Fred Berger has explained, the actor performed forty Dylan songs for the film on guitar, harmonica, “and singing live, take after take after take”.

Chalamet himself said, “It was important for me to sing and play live, because if I can actually do it, why should there be an element of artifice here? And I’m proud that we took that leap.”

Elle Fanning and Timothée Chalamet in A Complete Unknown

The actor's cheerleaders include Dylan himself who took to social media before Christmas to say: "Timmy’s a brilliant actor so I’m sure he’s going to be completely believable as me. Or a younger me. Or some other me."

He then added: "The film’s taken from Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric – a book that came out in 2015. It’s a fantastic retelling of events from the early ‘60s that led up to the fiasco at Newport. After you’ve seen the movie read the book."

It's subsequently emerged that Dylan personally went through the entire film script, offering suggestions and generally being enthusiastic about the project.

A Complete Unknown traces the Minnesota man’s infiltration of the 1960s folk scene in New York City, from where he ventures to New Jersey to visit his hero, Woody Guthrie (Scoot McNairy) in Greystone Park Hospital, where he’s battling Huntington’s disease. We also encounter other musical figures from the era, including Dylan’s muse-cum-partner Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro); folk legend Pete Seeger (Edward Norton); and musical collaborator Johnny Cash (Boyd Holbrook).

But most of all there’s Dylan, constantly refusing to be pigeonholed, bravely avoiding the obvious – and ignoring the hostility that approach brought with it. As he said, “These are the same people who tried to pin the name Judas on me. Judas, the most hated name in human history! And for what? For playing an electric guitar?” Not for him a career of sitting on a stool and playing ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’ for eternity.

Instead, the freewheeling Dylan embraced a plethora of musical personas, from croaking bluesman to protesting rocker, as well as friendly folky, country gent, gospel evangelist and suave crooner. He composed and recorded over 500 songs, and covered a similar number across the pop, rock, blues, country and folk canons. Along the way he was accused of not being able to sing, play the harmonica, play the guitar, or write melodies.

His Nobel Prize-winning lyrics were originally described by those with a dictatorial, neo-Stalinist attitude to how folk music should be performed, as “tenth-rate drivel”. His poetry was dismissed as “embarrassing fourth-grade schoolboy attempts”. However, those who handed down such denunciations from on high, have long since been lost down the foggy ruins of time.

His under-rated sense of humour came to the fore in the fantasy interviews in Martin Scorsese’s acclaimed 2019 documentary, Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story.

In another memorable moment in the Dylan cinematic universe, he played the intriguingly-named Alias in Sam Peckinpah’s neo-western Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid. That cult classic also saw Dylan compose the soundtrack, which included one of his signature tunes, ‘Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door’ – famously later covered by Guns N’ Roses on their mega-selling Use Your Illusion II.

Also to be found on “Best Albums Ever” lists are Highway 61 Revisited (1965); Blonde On Blonde (1966); Blood On The Tracks (1974); Oh Mercy (1989); and Time Out of Mind (1997); through to his most recent classic, Rough And Rowdy Ways (2020).

In 2020, Dylan released a 17-minute single that hit number one on Billboard’s Rock Digital Sales Chart. Titled ‘Murder Most Foul’, the track spun off from surreal flashes around the Kennedy assassination, to construct a portrait of an entire era.

Dylan also wrote books, presented his mischievously-scripted Theme Time Hour radio programmes, painted in his own imitable style, and created foundry art pieces. He rode out the ridicule of his crooner era, as well as the sloppy indifference of his Live Aid performance with Ron Wood and Keith Richards. He continually reinvented his songs, often beyond immediate recognition, to turn in extraordinary, age-defying concerts – as he did in 2022 at the 3Arena in Dublin.

Monica Barbaro and Timothée Chalamet in A Complete Unknown

Thus, A Complete Unknown is a welcome opportunity to celebrate one of the most influential and ground-breaking artists of the last century, a man up there with the likes of Picasso, Magritte, Yeats, Billie Holiday, Dylan Thomas and Miles Davis.

In Chalamet’s wonderful versions of Dylan classics, we get to hear afresh some of the greatest songs of the past six decades, and marvel that all of these were mostly written by one man.

As Bruce Springsteen once proffered:

“Elvis freed our bodies, but Bob Dylan freed our minds.”

• A Complete Unknown opens in cinemas January 17.

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 01 Apr 25

AI and Film: "The fear that technology will render us obsolete is palpable"

- Film And TV

- 27 Jan 25

WATCH: Timothée Chalamet covers Bob Dylan on SNL

- Film And TV

- 17 Jan 25

FILM OF THE WEEK: A Complete Unknown – by Roe McDermott

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 24 Dec 24

FILM OF THE WEEK: A Complete Unknown By Anne Margaret Daniel

- Film And TV

- 05 Dec 24

Bob Dylan reacts to A Complete Unknown - "Timmy’s a brilliant actor."

- Film And TV

- 06 Jul 23

Bob Dylan "personally annotated" script for upcoming biopic A Complete Unknown

- Film And TV

- 01 Jan 26