- Film And TV

- 21 Aug 22

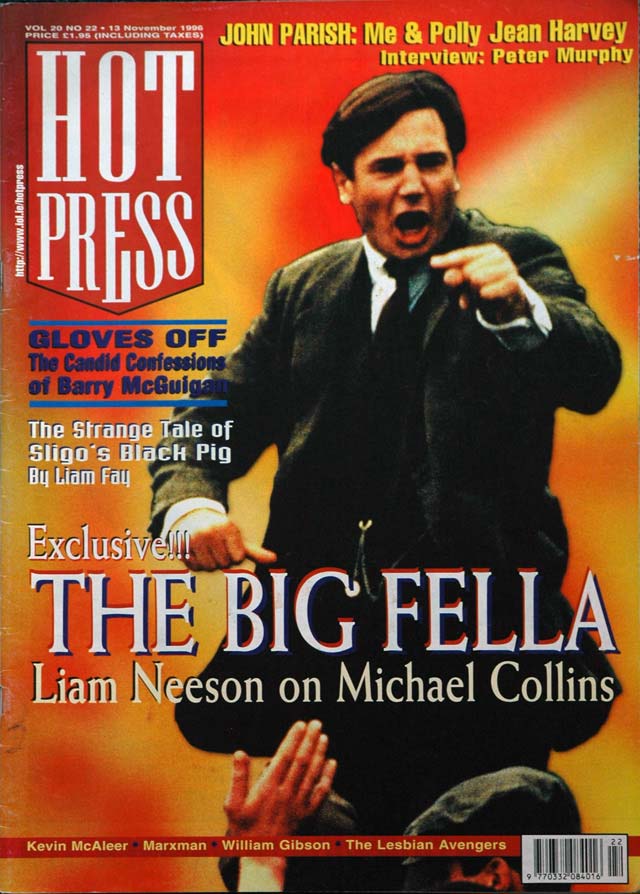

There had been huge competition to get a film made about Michael Collins. In the end, it was the great Irish director, the Academy Award-winning Neil Jordan who turned the idea into reality, in a film released to much controversy – and widespread acclaim – in 1996. One of Neil Jordan’s smartest moves was to cast Liam Neeson – fresh from his own Academy Award-winning success with Schindler’s List – as the great Irish revolutionary hero. In a Hot Press cover story at the time, we spoke to the actor from Ballymena about the film – and what it meant to him to play Michael Collins. It was, it turned out, a completely fascinating – and illuminating exchange republished here to mark the centenary of the death of the Irish revolutionary hero…

MICHAEL COLLINS: THE BIG FELLA

No Irish film in years has been more eagerly anticipated, nor more fiercely debated, than Neil Jordan’s Michael Collins. Opening soon in Ireland, it stars LIAM NEESON in the title role – in a performance which some critics are already tipping as an Oscar-winner. In this exclusive interview, conducted in America where he now lives, Neeson steps from the centre of the film into the centre of the controversy surrounding the film, arguing passionately that Michael Collins is a powerful blending of art and history in pursuit of the greater truth.

BY: ROBIN MILLING

Liam Neeson is both an Irish heart-throb and one of Hollywood’s favourite leading men. And with his new movie, Michael Collins, Neeson enhances his star status by putting in an Oscar-worthy performance.

The soft-spoken actor was born June 7, 1952 to staunch Catholic parents, in the predominantly Protestant town of Ballymena in County Antrim. He was christened William John Neeson but his family called him Liam in honour of a local priest. His parents worked In a Roman Catholic girls school – his late father as a custodian and his mother as a cook.

He originally sought a career as a teacher, attending Queen’s College in Belfast and majoring in physics, computer science, maths, and drama. The latter interest led him to join the prestigious Lyric Players Repertory Theatre, making

his professional debut in The Risen People. After two years there, he debuted in the Abbey Theatre in Brian Friel’s Translations and The Royal Exchange Theatre in Sean O’Casey’s The Plough And The Stars, for which he received a Best Actor Award.

Advertisement

His Oscar-winning performance in Steve Spielberg’s Schindler’s List changed his career forever, gaining him respect from both industry peers and fans alike. The following year he played in the equally impressive Rob Roy, opposite Jessica Lange.

Now, there’s Neil Jordan’s Michael Collins, a movie attended by much controversy – which, inspired by his deep belief in the value of the project, Liam Neeson is prepared to tackle head-on.

ROBIN MILLING: What does It mean to you to play this role?

LIAM NEESON: It’s something I'm still going through. Because, as you may know, I’ve been living with it for like 12 years, off and on. I thought there wouldn't be a high after Schindler's List. In fact, I thought about just giving up. Well, any script I read after Schindler’s List was like, "Aw fuck, what’s the point?” Which is kind of understandable. And then the light started to shine at the end of the tunnel, as regards Michael Collins becoming a possibility. And then it became a reality. So I just feel great about it. I don’t want this to

sound like a brag, but it feels like I’ve done It, you know? Other movies aren't interesting me, at the minute.

Why did it take 12 years?

Well, I think because of the war in Ireland. And I think obviously because of the controversy over the subject matter. And also, who the hell’s Neil Jordan, and who the hell's Liam Neeson, that he wants to play Michael Collins? That business aspect of it. Then, I'm sure you know the history of the making of this story. It goes way back to John Ford, up to John Houston, Robert Redford, to Kevin Costner, Michael Cimino. There’s been a litany of assorted names

from our industry. And they could never get it right. They could never encapsulate the epic with the intimate, which I feel (Neil) Jordan has done. They would always get it so far, and then it would crumble.

As a kid growing up in the North, what did you know about Michael Collins?

Advertisement

Because my mother was born and reared in Waterford, In the South, and my grandmother was a Dev follower, I had heard as a

small boy these names – De Valera and Collins – being talked about, and they were always discussed in hushed tones. I always remember – as if they were in the next room, or he lived next door, or something – that the relations were speaking this way. Because up until this present day, in parts of Ireland they still talk about them with passion . . . “Collins, oh, he was a traitor. Dev, oh, he didn’t do this.” The sign-post to Michael Collins’ birthplace is occasionally still graffitied over. So there’s still that thing. Anyway, that would kind of explain the hushed tones. And it was only when I was 18 or 19 that I started finding out about the history of Ireland. And then found where these men slotted into it, you know?

Is there any way that you can assume a role like this and not be perceived as taking one side or the other? If so, is that a concern to you?

No, It’s not. But I’m kind of aware of it as regards going to Europe,

and being in a situation like this with Irish and British journalists.

Even by saying there’s a war going on in Ireland – to certain journalists

back home, that's like saying, “Oh, I know what foot he kicks

with.” Do you know what I mean?

In real life, do you take a stand? Or are you able to see both

sides?

I am, but that’s as much to do with living in America, as I have

done now for ten years. Now, you’re talking about the present war,

are you? Or are you talking about that period of history?

The present.

I don’t know a great deal about the personalities involved,

because I'm not living there. But nothing really seems to have

changed from when I was growing up, unfortunately. Even with Bill

Clinton going there In November, as wonderful as those two days

Were.

Advertisement

Did you have any concern about the artistic licence taken with

historical fact in the film? Obviously, you had to play with the

truth to some extent.

I don't know about playing with the truth. Obviously, there’s characters

have been combined into one. There's a litany of things you

could say: “Well, that’s not accurate, that’s not accurate.” No, of

course, an armoured truck did not go Into Croke Park. But men went

in with machine guns and rifles. And yes, 13 people were killed, and

yes, 57 people were injured. So that’s true. Nell chose – I’m just

using this as an example – an armoured vehicle to show, perhaps,

the might and the power, and that anonymous face of the British

Empire. It was a wonderful and cinematic way of showing that

anonymous face of power. And a brilliant artistic device. So yes, it’s

not true. That didn’t happen. But it did. You know?

But most audiences tend to take their history off the screen.

And millions of people will now believe that a tank did go in

there.

Well, what’s the important thing to draw from it? The truth was

very murky, and dark. People don’t want to think about it or talk

about it. And I don’t know what Neil Jordan’s views are on the present

situation. I don’t know, and I don’t really care. He doesn’t care

about mine.

In the context of Irish history, do you see Collins as an heroic

figure?

I think he was very, very much an unsung hero. A real hero. If you

think of heroes worldwide – of those men and women who helped

form nations, they were sort of destined to be on this planet for a

short time, and they all had that same kind of dynamism and energy.

They had something to do that was inspired in some way.

Advertisement

He was 31 when he died, right?

He was 31, and he sat down with Winston Churchill, and

Birkenhead, and Lloyd George – at the age of 30. With the creme

de la creme of British politicians. There’s never been a cabinet like

that. And they loved him, after two months. They were writing him

fan letters and stuff. Birkenhead idolised Collins. That was part of

the trouble with his cohorts back home. When they knew Churchill

would be saying, “Michael, I was thinking about you today – something’s

happened in Egypt . . . ” They were buddies. They had such

admiration for each other. It’s weird to think of it. Well, it’s not weird

to think of it, actually.

What kind of reaction do you think the film will get when it

finally opens in England?

God knows. But I’m going to be there to confront it. Or hopefully,

not confront it. But we’ve had, for the past few weeks, editorials in

very staunch, right-wing newspapers that have just blown me away,

by saying how important this film is. In fact, there’s actually quite a

wonderful film critic over there who hails from the North of Ireland.

And hails from a very, very Protestant area. And I say that as a joke,

because I know this area very, very well. There’s a saying back home, “He’s as black as your boot,” meaning he’s that Protestant.He’s like really a kind of Pilgrim father – thou shalt not. And I say

that lightly, but he’s a fabulous critic. But the only time he has mentioned

me in any films over the past ten years, it’s just been begrudgingly. Even Schindler’s List – he just about spelled my name. Everybody got reviews, and I just got mentioned. But of Michael Collins, (the film’s producer) Stephen Woolley said, “We’re having a special screening for this critic.” And I said, “Well, do you want me to

lay a bet? This guy’s just going to needle us up to the wall. Why are you pandering to him? Why are you giving him a special screening. Let him just see it along with everybody.” He said, "No, no, no. I just

feel right about it.” So I said, “A crisp $100 note is yours if this guy likes the film.” Well, he wrote this stunning editorial for the Evening Standard in London. I had to take my hat off to him.

After all the research work you’ve done, what do you feel is the

truth about the allegations that De Valera basically “set up”

Michael Collins?

I don’t think he set him up at all, no. And I don’t think Neil Jordan sets Dev up in the film. It’s just that he was in the area. And he had lost control. These youngbloods – the Irregulars, as they were known, these anti-treatyites – wanted to run amok. And De Valera had actually lost control. He was down there to try and take these Republican factions and gather them together. He said, “Look guys, we have to have a plan here.” In the interim, Collins was driving through to meet neutral forces, who could act as arbiters between the pro-treatyites and the anti-treatyites. Now, there’s all sorts of speculation – and God knows, there’s so many articles and books written about it – that Dev was there, he even drove through Béal na Bláth half an hour before Collins, or half an hour after, I cannot remember. At most, I think Collins, if he’d had the chance, before he left the area he would have met De Valera. They would have met, to say, “Let's stop this fucking madness." In the back of my mind, I know that's why Collins was there.

Did De Valera order the ambush?

Advertisement

No, he didn't. There was a member of Collins’ convoy who the night before in Cork said to somebody: “I hear there’s roadblocks. Could you tell me what's set up?" And of course he was talking to an anti-treatyite. And this guy knew the other guy was a member of Collins’ envoy. I mean, Collins would have gone crazy if he’d heard that. That giving of apparently innocent information. So the guy then went and told his commanding officer. “Look, I’ve spoken to someone in Collins' entourage. They've asked about road blocks along these certain road. They're obviously going to drive there. Let's set up an ambush.” That’s what happened. According to my research; that's what I found out.

You're quite convincing as Michael Collins. Do you think in real

life there would have been a possibility that you could have

been a person like that – a revolutionary?

Could I have been? I don’t think so, no. I don't have that dynamism that he had. I love my country, but would I die for it? I don't know. I don’t think so.

Would you fight for It?

I would fight for an injustice. If it hit me on the head long enough, I certainly would.

Did you encounter any opposition from De Valera supporters

during shooting? I mean, all around, there are still people who

are Dev people.

Individually, no. Every so often, during the shooting of it, some

journalist would take a snipe at you, in some little dipshit article.

Someone just trying to stick a knife in, who hadn't read the script.

And there's been a few of those. Notably in the Irish papers. There’s

one eccentric priest who has written about how Collins died. He

claims to know it was somebody on the back of a jeep who did it.

He’s got this weird, eccentric thing. Anyway, he was writing letters, a

lot of letters, into the Cork Examiner. He said: “I see the casting with

this film was atrocious. Liam Neeson’s like a giraffe.” I’m quoting

him. “And Julia Roberts, when she smiles, her teeth are like tombstones."

I mean, this was getting printed. “Kevin Costner should

have played that part. His voice – his voice is quite high, and that's

how Collins spoke." And all this stuff was getting printed. I’m dying

to meet him when I go over. I hope he enjoys it.

Advertisement

Is there a process to the way you approach an acting role?

I’m not sure if I have a process. People have asked me, “Are you

a method actor?” I say, “I use whatever method works.” Because it's

always different, from one situation to the next.

Are there moments when you're preparing, when you just feel

that you’re just not getting under the skin of the character? Or

once you’re on the set, are you prepared to go?

Usually prepared to go. But I’m a great respecter of directors and

writers. If I trust that relationship, then I'll walk over hot coals for

them, I don’t care. If they say, “Do the scene standing on your

head,” I’ll feel, “Well, there's a reason for doing that." And it’s also

part of the actor's job. You should be able to do a speech standing

on your head. And sometimes I've been in situations where I've

seen actors and actresses say, “No, I'm not doing that. I’m not doing

it." And it's like, well, you’re kind of blinkering yourself if you don't.

Just do it. Even to find out that it doesn't work. Just stretch a bit. So

that’s my process, if there is such. Working with several people like Aidan Quinn, Alan Rickman,

Stephen Rea – we could do scenes, and we could have an unspoken

language with each other. We don’t have to say, “What if I did

this, or you're doing that?" It all flowed, which was great. So in that

sense, the casting was not only accurate, but very, very fluid. When

we were actually working, it was never a hang-up because of actors.

Did you recommend Julia Roberts for the film?

No, no. Neil had met Julia, and she was terribly keen to do the

project. Interestingly enough, she heard about Michael Collins from

me, ten years ago. And Neil was very, very sure that’s who he wanted.

There were rumours of re-shoots and so forth.

Advertisement

These were false rumours. There were no re-shoots but we did

shoot a couple of extra explanatory scenes.

But no love scene that was inserted, as has been suggested?

Oh, no. That was all just rumours. Totally untrue.

What's it like for an actor to play a role like Oskar Schindler?

Well, you're kind of blessed, and lucky, because we're all aware of

the power of the moving image, and how it can reach and hit millions

of people. And the sway that it has. I don’t think movies

change society. I think they focus on issues and points. Of course

they do. I just feel very proud. Whatever happens to me, I do feel

Schindler's List will be kept in a sealed vault. No matter what happens,

to the planet, if it disintegrates – I feel it’s one of those

movies. And hopefully, the same with Michael Collins.

Does playing those kind of roles make it hard for you to look at

other scripts?

Yeah, it does. And I'm a working-class Irish guy – I like to work. If

you're an actor, or any artist or craftsman, you have to practise your

craft. So there's a side of me that wants to, if I read something, say,

“Yeah, I could do this,” and just do it. But then the other side says,

“No, you have to wait - just wait. It’s not good enough.” ■

Advertisement

• This interview first appeared in Hot Press in the issue dated 13 November 1996.