- Film And TV

- 03 Feb 25

Director Sinead O'Shea discusses her new documentary Blue Road, which examines the life of Edna O'Brien, one of Ireland's most acclaimed and influential authors, whose work also proved a lightning rod for controversy

Few writers have faced as much judgment and censure as Edna O’Brien, whose groundbreaking novels unapologetically explored the inner lives and desires of women. From her 1960 debut The Country Girls – banned and burned in Ireland for its frankness – to later works that delved into taboo subjects like sexuality, motherhood, and trauma, O’Brien’s voice was a lightning rod for controversy.

Despite the backlash, her work shattered silence, challenging oppressive norms and giving women a literary mirror in which to see themselves. O’Brien’s resilience turned shame into a platform, cementing her legacy as a fearless chronicler of women’s experiences.

O’Brien died last year aged 93, but not before collaborating with director Sinead O’Shea on her layered, tender and insightful documentary Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story. It features new interviews with O’Brien as well as a veritable feast of photographs, diary entries and archival footage from throughout O’Brien’s life and career.

O’Shea’s stirring documentary delves into the author’s prolific talent and whirlwind personal life – parties with Sean Connery and Marianne Faithful and affairs with British politicians abound. But importantly, the documentary also illustrates how O’Brien was constantly fighting against patriarchal influence: that of her controlling father; her abusive ex-husband Ernest Gébler, who resented her success; and a sexist society which scorned and silenced her work.

O’Shea brings themes of trauma and resistance to all of her work, which includes the acclaimed films Pray For Our Sinners and A Mother Brings Her Son To Be Shot. She notes that despite studying English Literature in college, she never saw O’Brien’s work being taken seriously.

Advertisement

Director Sinead O'Shea

Director Sinead O'Shea“I can’t remember her name ever coming up,” she says. “I remember any time she was ever mentioned, there was definitely an association of frothiness, something very trivial and shallow, and so nothing to do with literature. But I now think this was no coincidence. Having made the film, I think it’s a mix of conspiracy – it’s both that the husband was really pulling strings in Ireland, but also that Ireland at the time was so receptive to the idea that this woman was actually shit.

“It’s fascinating that older women did have a sense of her literary work, but for younger women she was completely non-existent.”

It wasn’t until O’Shea was asked to profile O’Brien for a magazine that she read The Country Girls.

“It was so good,” she says. “I did feel like she was talking about my own adolescence, which was the 1990s, but it still felt very relevant to me and how I grew up. And then I read her memoir, Country Girl, and that was incredible. The life she had, it’s one of the great lives of the 20th century.

“She encounters everyone, and these incredible personal dramas happen to her. And all the stuff with the husband, it’s beyond villainous, as well as the reception she got here.”

Advertisement

O’Brien’s marriage to writer Gébler was marked by control, abuse and resentment, and O’Brien finally left after he viciously assaulted her. But Gébler remained obsessed with her, scrawling insults in her personal diaries and claiming that he had actually written her books – the personal, intimate stories of being a young Irish woman.

“What’s so interesting about the annotations is that they then paved the way for how Edna is understood by the rest of Ireland, because everything becomes the echo of what Ernest has written in those early days,” says O’Shea. “The annotations stop in the ‘60s when she leaves him, but he doesn’t stop. He just keeps spreading this rumour that she hasn’t written her own books. I had a friend from college in English with me, who said, ‘I was always told she hadn’t written her own books.’”

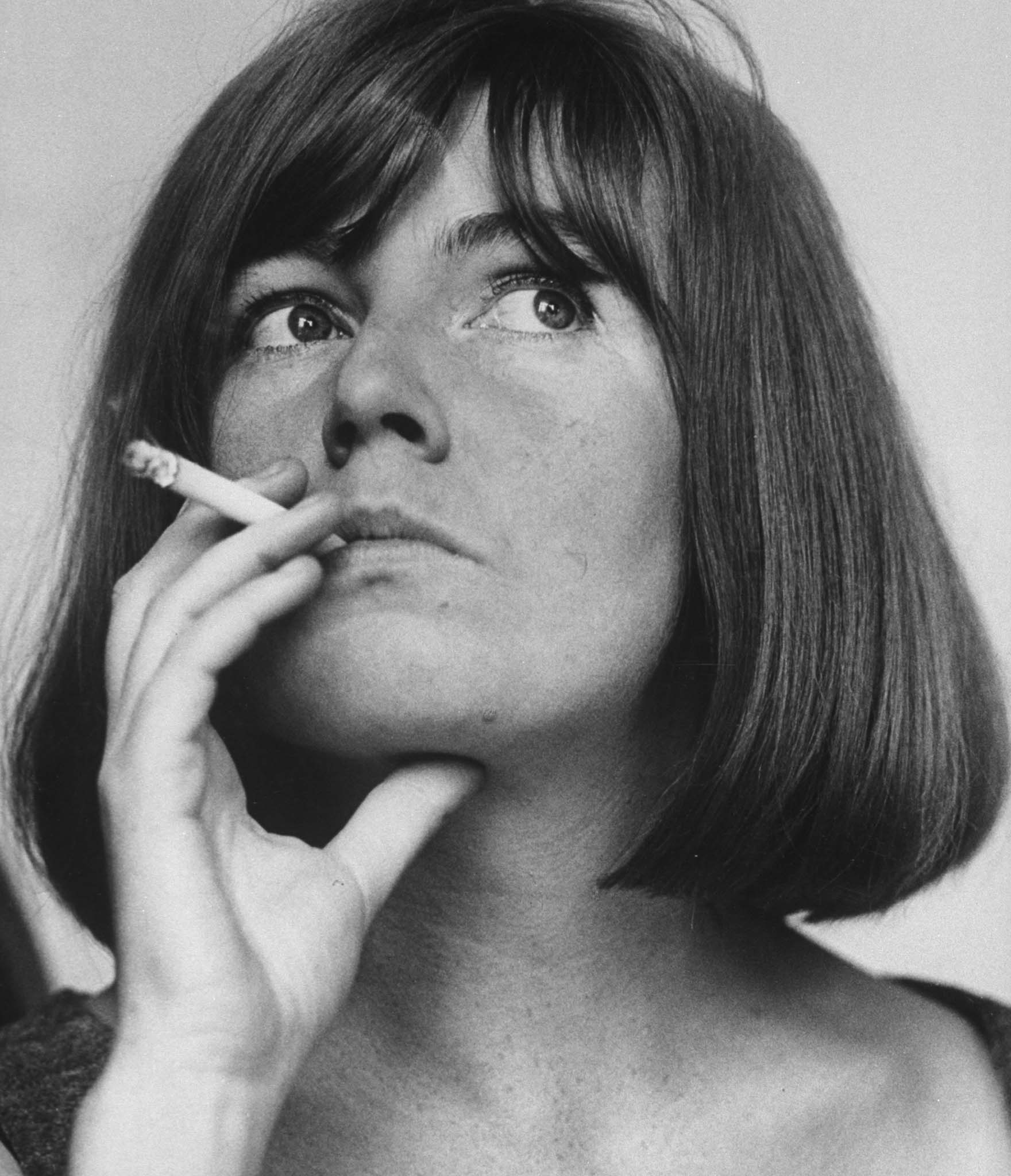

SPECIAL PRICE. The Irish novelist Edna O'Brien pictured in 1970.

SPECIAL PRICE. The Irish novelist Edna O'Brien pictured in 1970.O’Shea conducted several interviews with O’Brien, who was in poor health, but still sharp and ready to talk about her life and writing. The director describes her as “so charismatic, so compelling, so funny, so clever”, even as some of their interviews were cut short by O’Brien’s health. As O’Shea collected archive footage and received permission to read O’Brien’s revealing and often salacious diaries, she was struck by the author’s talent and ambition, but also her vulnerability and the amount of trauma she endured from a sexist society.

At one point in the film, O’Shea asks O’Brien if she received enough care and support after everything she endured, and the writer simply repeats, “No. No. No. No. No.”

Much like Kathryn Ferguson’s beautiful documentary Nothing Compares wasn’t just about Sinead O’Connor, but was a portrait of a society that tried to silence women, Blue Road is also a portrait of Ireland’s attitude towards women who were outspoken about their inner lives, struggles, desire and pleasure.

Advertisement

“There is a sense of the patriarchy in all my films, even though it’s not that overt. I am, I think, quite mild mannered, but there is maybe a bridling there!” laughs O’Shea. “I knew this had the potential to be a film that could tell this big story, as well as this really interesting, juicy tale of a terribly charismatic woman. I guess if you’re going to make a documentary, the history of something informs every second of it. There’s always context.”

O’Brien died before Blue Road's release, and her funeral becomes a beautiful sequence in the documentary. O’Shea hopes the film allows viewers to not only appreciate O’Brien, but also to be inspired by her.

“It would be nice if it could inspire people to be tenacious and do creative things, because Edna did not take the safe road at any point,” she says. “And while she suffered for it, it really was a magnificent life. It’s pretty great that we can all now enjoy it and learn from it.”

• Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story is in cinemas from January 31.