- Film And TV

- 13 Oct 22

Kathryn Ferguson on Nothing Compares: "It’s so phenomenal to hear Sinéad O'Connor say that she doesn’t regret a bloody thing"

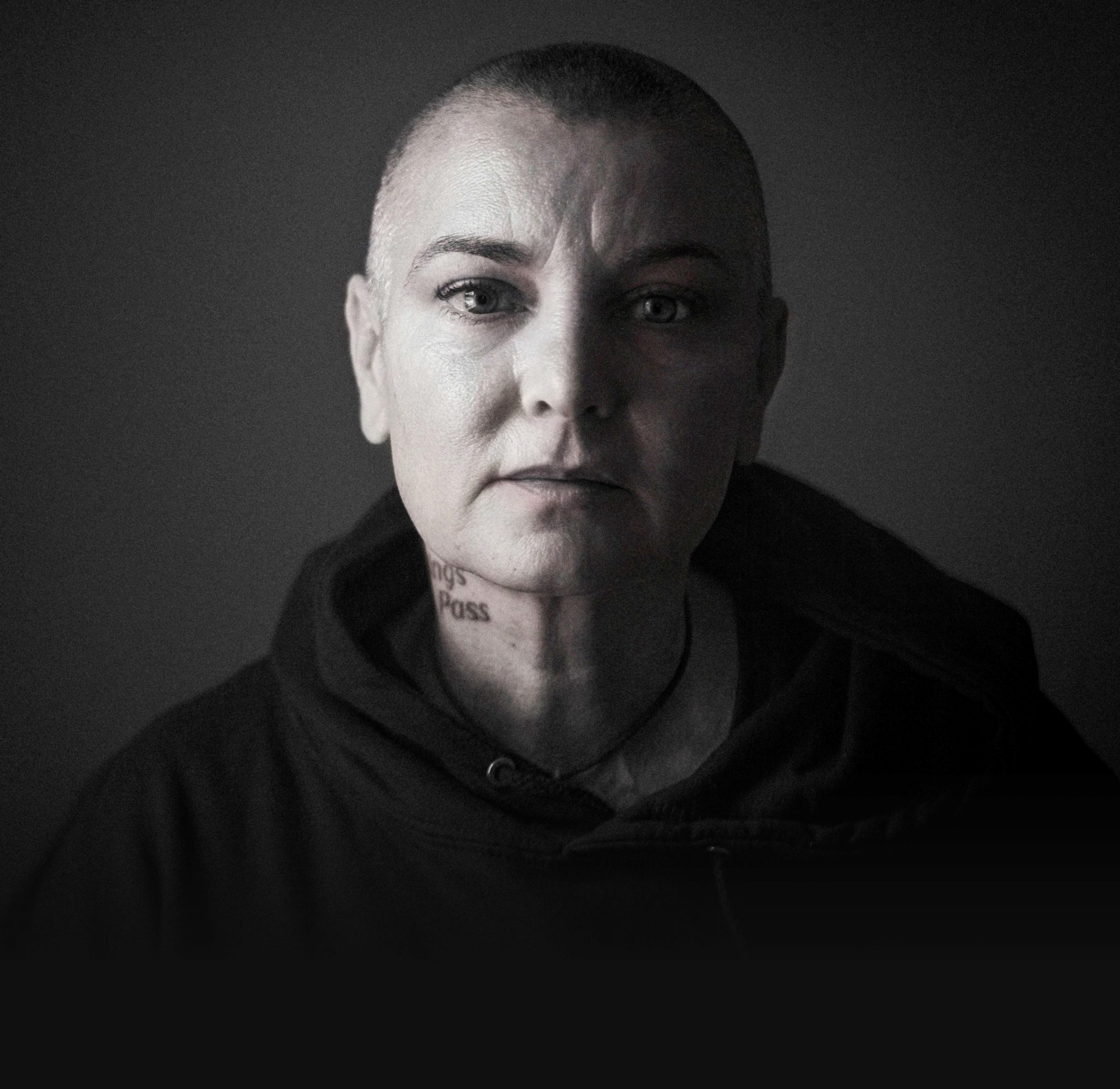

Director Kathryn Ferguson discusses her compelling Sinéad O’Connor documentary Nothing Compares, which examines how the legendary singer rose above media attacks early in her career, to become an eloquent voice for the marginalised. Portrait: Benjamin Eagle.

In so many ways, it’s baffling that there hasn’t been a documentary made about Irish singer, writer and activist Sinéad O’Connor – and thankfully, a sublime one is just about to hit cinemas.

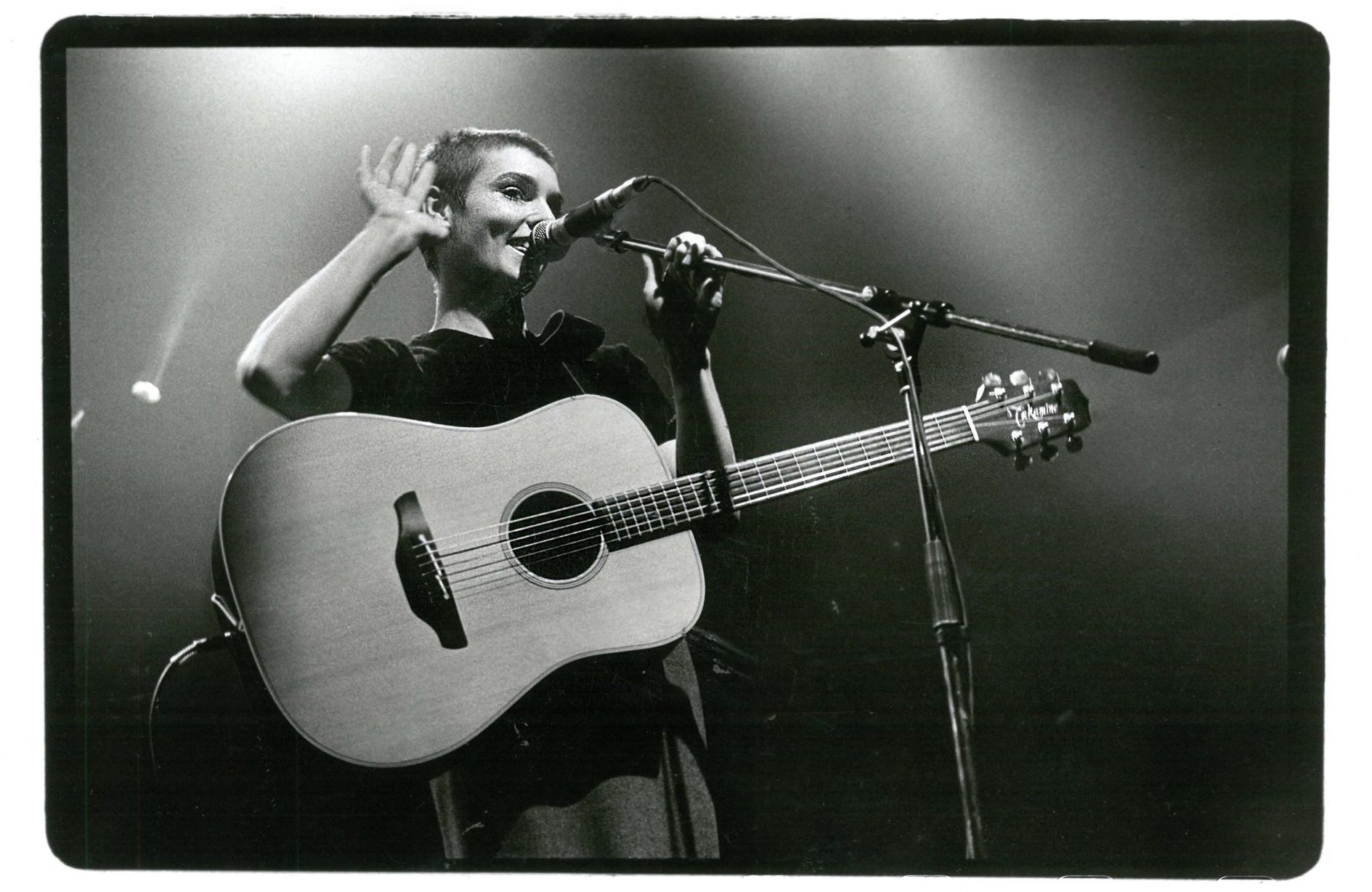

Belfast-born director Kathryn Ferguson’s Nothing Compares is a stirring, respectful, empathetic and galvanising documentary about O’Connor’s early career, and how the singer’s strong beliefs and desire for equality was viciously policed. The film also acts as a portrait of Ireland’s political and cultural evolution since the 1980s – which is fitting, because that’s when Ferguson first fell in love with the singer.

“I was introduced to Sinéad in the late ’80s by my father,” she explains. “I grew up in Belfast and he was a mega fan. I was eight or so when The Lion And The Cobra came out, so I was introduced to her music as it was played during car journeys through Belfast in the late ’80s and early ’90s!

In my early teens, as soon as I found Sinéad, and loved her music and everything she stood for, I was really horrified to see her treatment in the media. It made a huge dent in my early teenage life.”

Ferguson’s fascination with O’Connor grew, and when she began studying and making films, she knew that she wanted to work with the singer in some way. In 2011, when Ferguson was completing a Masters programme, she made an experimental short film called Mathair, and knew only one woman could provide the soundtrack.

“Máthair is all about women’s experience, and my own mother and Ireland under Catholicism,” explains the director.

“I reached out to her then manager Fachtna O Ceallaigh and asked if I could possibly get the stems of Sinéad’s music, to deconstruct it for this very strange film, and was delighted that he agreed. That led to the team coming back to me two years later, asking me to direct her music video for ‘4th And Vine’, which I think was her first video in 15 years. So it was a very organic meeting of Sinéad and the team. That was 2012 and I got to go to her house and meet her. It was incredible, especially given that I just carried this burning love and hunger to work with her, and maybe do something more at a later stage.”

Ferguson kept in touch with Sinéad and her team over the years and always wondered why O’Connor’s brilliance, both in her music and activism, hadn’t been immortalised in a documentary. Then, in 2018, the rapidly changing political and cultural climate threw fuel on the fire, and she was inspired to finally pursue her dream project.

“Around 2018, there was so much happening politically, there was such a collision of events both in North America and at home,” she recalls. “With Repeal and Trump coming into power and the women’s marches, so much seemed to coalesce. And I thought, ‘I’m going to try get a one-pager done. Why is Sinéad not part of this conversation when she had surely – if not directly, certainly indirectly – influenced so much of what’s happening?’”

Ferguson created a pitch for a documentary, but she knew it was never going to be a biopic. Instead, the film focuses on O’Connor’s phenomenal rise to worldwide fame between 1987 and 1993; the ways she used her platform to address social issues such as Church abuse, misogyny and racism; and the vicious backlash she received for speaking truth to power.

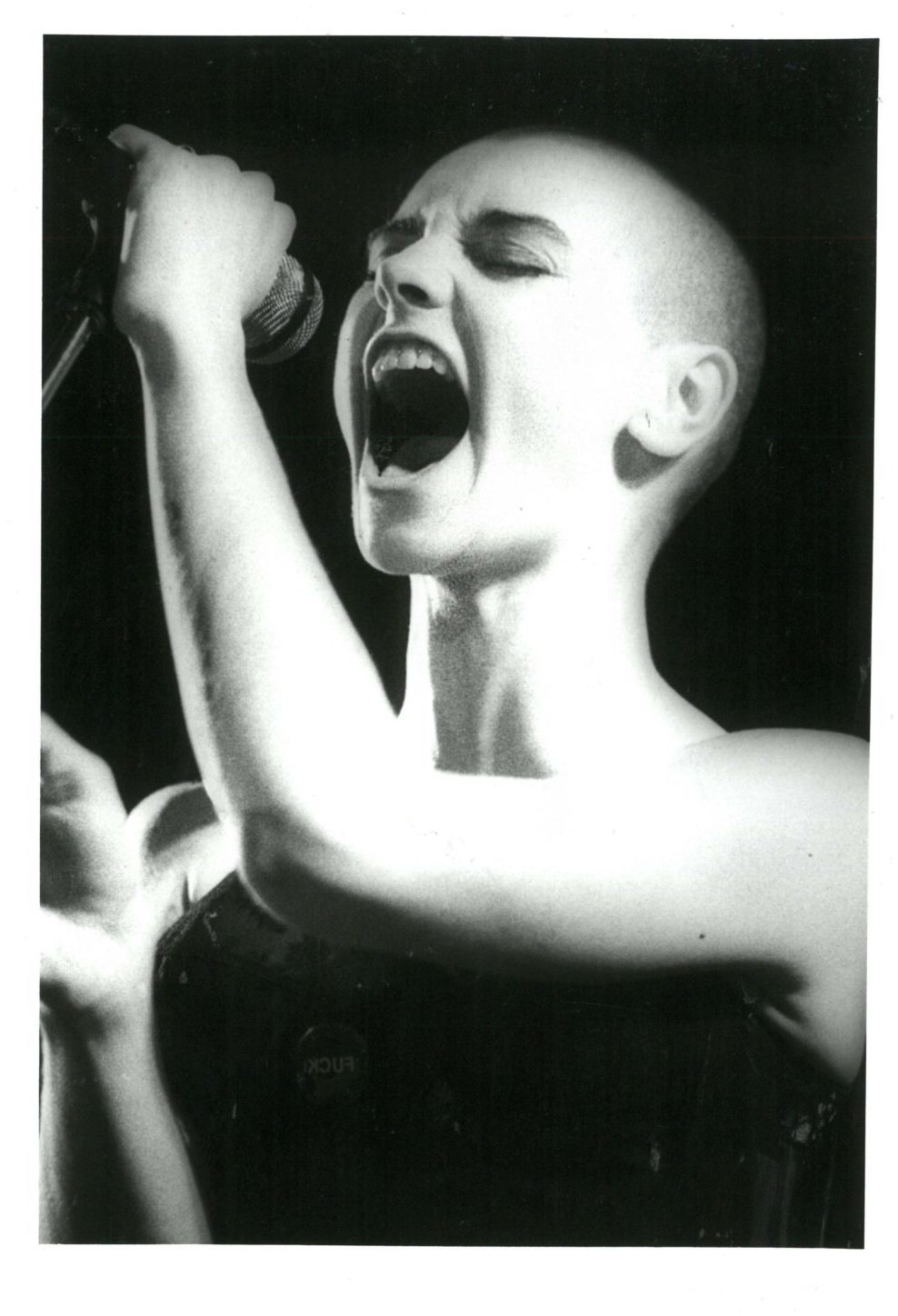

The film features incredible archival footage of Sinéad rehearsing, performing and being interviewed during the late ’80s and early ’90s. It also features a new voiceover interview with the singer, reflecting on the abuse she suffered at the hands of her mother; the Church abuse that was rampant in Ireland, damaging generations of Irish families; and the way she faced intense scrutiny and vitriol for daring to be a woman who spoke her mind.

Ferguson’s incredibly edited film shows how the star, despite her incredible talent – and her astute criticisms of the Church in Ireland, the need for gender equality and abortion rights, and the realities of racism in America – was relentlessly attacked. Interviews with Gay Byrne on The Late Late Show start with condescending comments about her shaved head – a point of utter obsession for the media – and dismissals of her political and cultural criticisms.

In the States, she was branded as eccentric, ungrateful and eventually dangerous, as she used her platform to speak out against injustice. In 1990, she refused to let the American national anthem be performed at her concert in the Garden State Arts Center in New Jersey; a decision that led to several radio stations boycotting her music, the public destruction of her CDs and several threats of violence against her – including one from Frank Sinatra.

At his own concert in New Jersey, Sinatra told the crowd that he “wished he could meet her so he could kick her”, and was also reported to have advised her to leave the country because her actions were “unforgivable.” He added, amid thunderous applause, “For her sake, we’d better never meet.” It wouldn’t be the last time a famous man publicly threatened O’Connor and was rewarded for it.

After boycotting the 1991 Grammys and penning an open letter that highlighted inequality, exploitation and a lack of social consciousness within the music industry, O’Connor then made her now infamous appearance on Saturday Night Live in 1992 – and the world lost its mind.

On October 3 of that year, the singer took to the stage of SNL in New York City. She was performing an a capella version of Bob Marley’s ‘War’; a song about racism and inequality. But O’Connor changed some of the lyrics, referring to the victims of child abuse, rather than racism.

As she came to the end of the song, she stared defiantly down the camera lens, singing to the millions of viewers “We have confidence in good over evil” – and held up a photo. In rehearsal, this had been a photo of an orphaned, refugee child. But live on television, she held up a picture of then-Pope John Paul II and tore it up, tossing the pieces at the camera, saying, “Fight the real enemy!”

The audience fell silent. No-one knew what to do. O’Connor walked offstage to no applause and the next day, the media was in a frenzy. The New York Daily News labelled her a “holy terror”. She was labelled “crazy”, a “bitch”; her albums were literally crushed by a steamroller outside Chrysalis Records’ Rockefeller Center. The next week on SNL, guest host Joe Pesci declared, “She’s lucky it wasn’t my show. Cause if it was my show, I would have given her such a smack”, and was met with rapturous applause.

The audience fell silent. No-one knew what to do. O’Connor walked offstage to no applause and the next day, the media was in a frenzy. The New York Daily News labelled her a “holy terror”. She was labelled “crazy”, a “bitch”; her albums were literally crushed by a steamroller outside Chrysalis Records’ Rockefeller Center. The next week on SNL, guest host Joe Pesci declared, “She’s lucky it wasn’t my show. Cause if it was my show, I would have given her such a smack”, and was met with rapturous applause.

This type of backlash to a female artist speaking her mind isn’t isolated. Nearly a decade later, country act Dixie Chicks – then one of America’s most successful music groups – denigrated George W. Bush during a concert in Shoreditch, declaring, “We don’t want this war, this violence, and we’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas”, nine days before the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The backlash was swift, mighty, and echoed the one faced by O’Connor. The Dixie Chicks’ records were publicly bulldozed. Radios refused to play their music. And their career never fully recovered.

But in 1992, O’Connor was on her own, experiencing a very particular type of cultural backlash. She was outspoken against misogyny, racism, institutional religion and American nationalism – the very foundation of America itself. The media attacks, the destruction of her CDs, and the way male celebrities used her to bolster their own image, was very deliberately public and excessive – because, while it was focused on Sinéad, it was also a form of social and cultural theatre that acted as a warning to all women: Stay in your place. Don’t get too mouthy. Don’t speak the truths that we don’t want to address. If you do, we will destroy you, and people will applaud.

These messages became all too prescient again around 2018, when the #MeToo moment was happening, Irish women were fighting for abortion rights, and an admitted sexual predator had been voted into the White House. Ferguson, who had watched O’Connor’s career and the backlash against her unfurl, was reminded of how much we needed strong women, and how much Sinéad’s legacy had influenced both her and current generations of young women.

“She was vital,” Ferguson notes. “She was so exciting; she was brave and bold and we all really needed her as women in Ireland. We really needed to see that she would stand up and say the things that were unpalatable. She stuck to her guns, she kept her integrity and showed us how to do that.

“And I know as Irish women, she was vital and we needed her, but my god, the amount of people we’ve met on this journey with this film – she was needed all over the world. It’s been fascinating. Seeing the film play in countries like Mexico and Poland, very Catholic countries, and seeing the response has been incredible.”

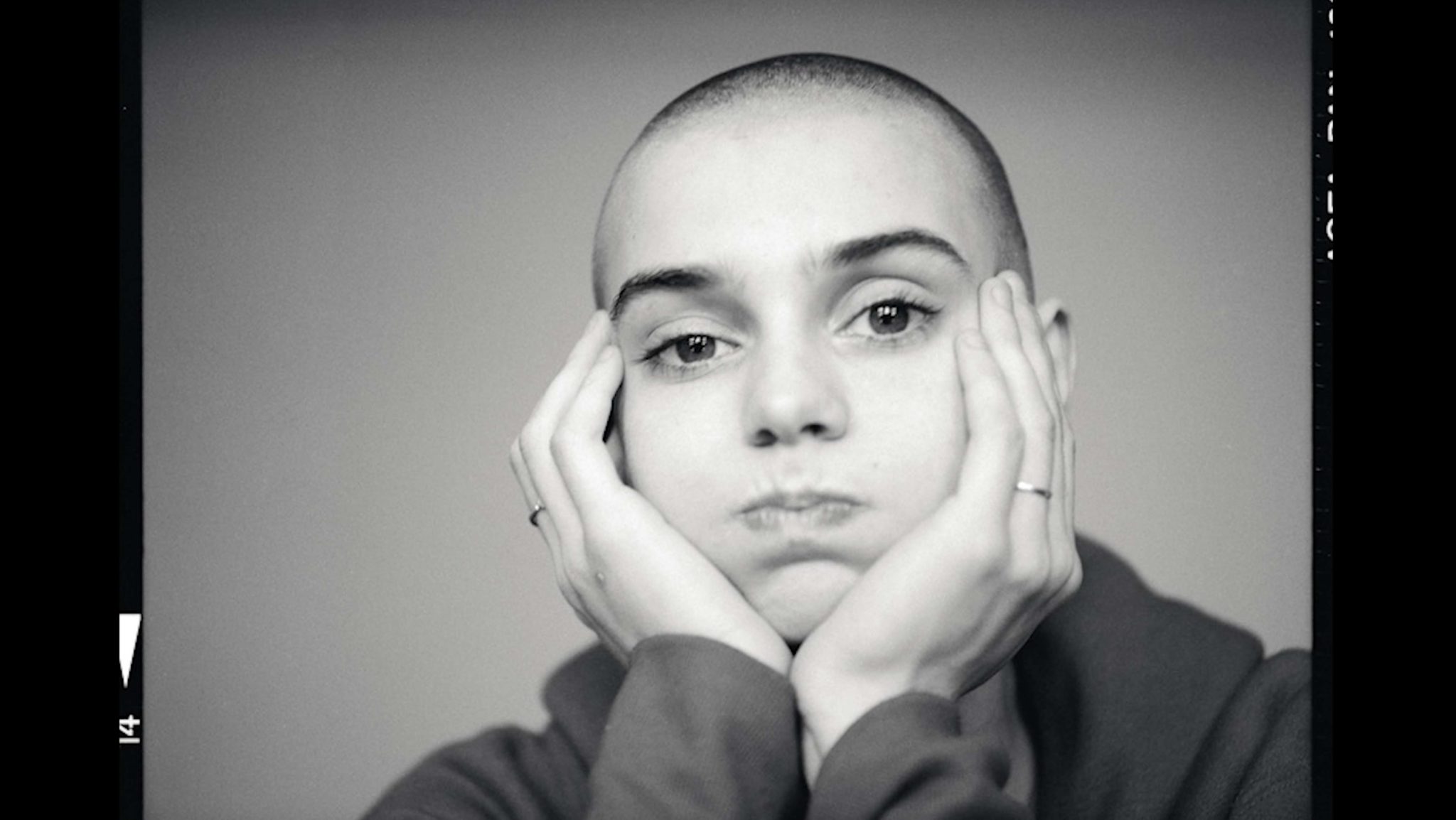

Sinead O'Connor by Robbie Jones - March 1988.

Sinead O'Connor by Robbie Jones - March 1988.As Ferguson started looking through over 100 hours of clips, she and her team began thinking of how best to structure the film, and how to make it while being respectful to O’Connor, who has been very vocal about her mental health struggles. Ferguson decided not to have Sinéad herself on camera, instead interviewing her over a weekend and using the voiceover as narration.

“From the offset, the cornerstone was we wanted to make this with respect,” says the director. “We wanted to just have Sinéad’s voice telling her story, because it was the voice that had been really reduced over the years. It was never going to be a biopic, we wanted to create a film that was very much set in the era of 1987 to 1993, and then there’s a hard finish. We wanted to let her tell her story with hindsight.

“But I’m delighted that we were able to do that, and to have such a brilliant, thoughtful, funny, reflective interview. That was gold. It’s so phenomenal to hear her say that she doesn’t regret a bloody thing – that’s key. There are no regrets.”

The film becomes both an exploration of this period of O’Connor’s career, and a cultural exploration of how Ireland, America and their treatment of women has evolved – or, in some depressing ways, regressed. This structure is insightful, evocative and, most admirably, avoids any air of the exploitation that is ripe within documentaries about famous women. Recent Amy Winehouse and Whitney Houston ones have felt tasteless and sensationalist in their depiction of women who were built up by the media, only to be torn down – and then used again by documentarians in order to create a cautionary tale, a pity porn film, and of course a steep profit.

“I have been hyper aware of those kinds of documentaries and we wanted to do something completely the antithesis of that,” asserts Ferguson. “We wanted to avoid the trope of telling iconoclastic women’s stories through a tragic heroine lens, because I as a woman, and a lover of documentaries and musicians, particularly female musician, didn’t want to see another one. I wanted a very different approach. And I wanted viewers to be furious like I am, but I wanted them to be galvanised – particularly young women. That was key. And that seems to have been the response so far.

“In festivals, certainly, the amount of young women that come up with their eyes flashing at the end of these screenings. Honestly, It makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up. They’re like, ‘Oh my God. We didn’t know any of this. What we knew about Sinéad is that she was so bad. She was bad’ – and that’s coming from their parents or the media. They’ve just been told that she did something bad, but then you see their response.

“And you see that we need Sinéads right now! We need women kicking the door down. It’s critical and I’m just hoping that – off the back of her incredible book, and her final comment at the end about hoping to be a seed – if she could really inspire the next generation, that would be fabulous.”

And Ferguson is already seeing the impact of the film on young women.

“When the film launched at Sundance, these two young Latinx podcasters came up to me and said, ‘We need to say exactly what we think. It’s urgent that we have to use our voices and stand by what we believe in.’ To me, that’s everything. That’s the ripple effect you dream of, that it inspires young women and every community in the world. Because that’s what Sinéad is about, speaking out for marginalised communities and standing up for them.”

• Nothing Compares is in cinemas now.

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 16 Feb 24

Bob Marley: One Love album is out now

- Film And TV

- 06 Jul 23

Trailer released for new Bob Marley biopic

RELATED

- Competitions

- 07 Mar 22

WIN: 2 Tickets to Special Screening of Rebel Dread in the IFI, Q&A with Don Letts

- Film And TV

- 14 Feb 22

Kingsley Ben-Adir to play Bob Marley in new biopic from King Richard director

- Film And TV

- 07 Oct 20

'I Can See Clearly Now' singer Johnny Nash dies, aged 80

- Film And TV

- 31 Mar 20

Bob Marley: Legacy series continues with 'Women Rising'

- Film And TV

- 17 Feb 20