- Film And TV

- 14 Nov 22

LYRA director Alison Millar: "I want people to learn about the North through Lyra McKee, because everything she did came straight from the heart"

Director Alison Millar discusses her documentary on gifted journalist Lyra McKee, whose shocking killing in 2019 was one of the darkest moments in Northern Ireland’s recent history.

“That bullet that killed Lyra didn’t stop travelling.” This quote from Lyra McKee’s sister Nichola, who appears prominently in Alison Millar’s new documentary LYRA, epitomises the immense grief brimming through each second of the film, which recently arrived in Irish and UK cinemas after weeks of acclaimed festival screenings. A single bullet that sent shockwaves around the world on the eve of Good Friday 2019, with the repercussions captured on camera by the McKee family and Lyra’s close friend, Alison Millar.

Executively produced by Hillary Rodham Clinton’s HiddenLight Productions, LYRA is a beautiful and heartfelt film about the life and death of the internationally renowned Northern Irish investigative journalist, who was just 29 when she was killed by gunfire during disturbances in Derry. Raised in working-class, war-torn Belfast, Lyra went on to highlight the consequences of the Troubles, seeking justice for crimes that had been forgotten.

Using hours of voice recordings from Lyra’s own mobile, computer and dictaphone, the documentary – which won the Audience Award at the Cork Film Festival – seeks answers to her senseless killing through Lyra’s own work and words. Notably, the score was composed by acclaimed Northern Irish producer David Holmes.

LYRA seamlessly paints a complex picture of Northern Ireland’s political history, bringing into sharp focus the ways in which the 1998 Good Friday agreement – with its promised end to violence for future generations – has struggled to be fully realised. Hot Press spoke with BAFTA, IFTA and Prix Italia winning filmmaker Alison Millar about creating yet another emotionally compelling documentary, with a gut-wrenchingly personal connection to the subject. Despite a small crew of helpers and patrons, director Alison Millar – a friend of the late journalist – was determined to get the documentary funded, after Lyra’s family specially requested for her to take the reins.

“We were so busy fundraising to make the actual film, which meant that we didn’t all fall off the edge of the cliff until we watched it back, after trying to do the best job we could,” says Millar.

“Maybe you don’t feel the power of LYRA until you sit in a room with an audience and realise there’s a wave going through the place. Everyone is affected. David Holmes was like that when we sent him the first cut to work on. He showed it to a close friend after scoring it and the two of them were in bits.

“David works from his heart, he just feels his way through. It really is a notion he gets in his head. I’ve never met anyone quite like that. What can I say about David other than he’s amazing. I’ve never felt safer. That was very emotional. He was the first person we were handing a cut to, and there were quite big moments sitting with him. We were all in tears because we felt Lyra’s presence hugely. That sounds off, but we really did.”

Lyra's partner, Sara.

Lyra's partner, Sara.The media interest in Lyra McKee must have felt completely overwhelming. How does Millar cope with having to speak to the media about the loss of her friend, three years on?

“It was hard to talk about the film with the media at first, but I’m floored just sitting here thinking, ‘Is this really happening?’” she responds, shaking her head. “We made the documentary with hardly anything, it was a wing and a prayer. A lot of love, heart and people like David. He called me up and asked to do it, and I told him I didn’t have a budget. I was completely broke and he said, ‘I don’t want any money. I’m doing this for Lyra, I want to do this film’. That’s the magic of her, and people’s reaction to the murder. The whole island was frozen.

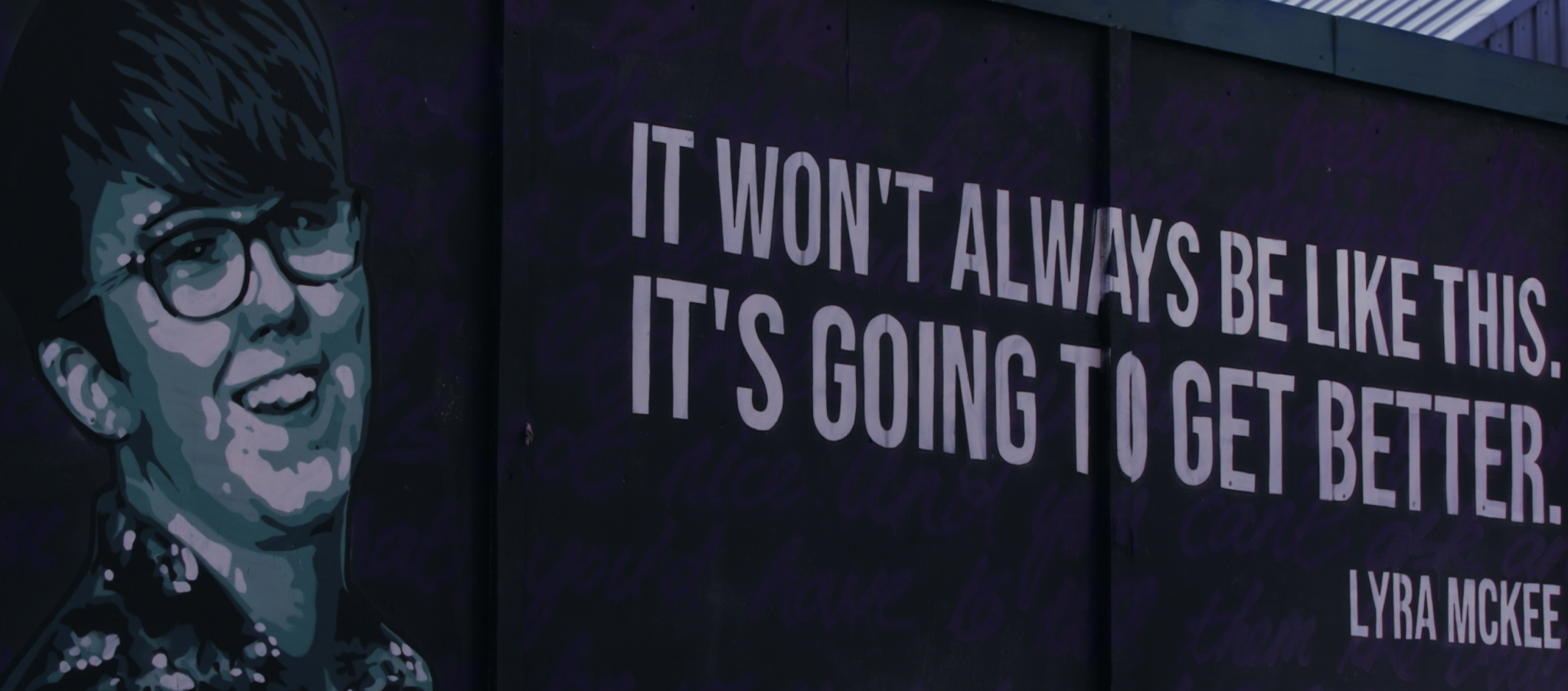

“I almost can’t believe that people will be going to the cinema to see the documentary about her story. There’s hard moments. Last night I was with her nephew Andrew in this place called The Sunflower. She’s got a famous Belfast mural down there. He always touches it when he goes past. We’d been doing press and went for a drink after, and just as we were coming out, my editor called me to say we’d been shortlisted for this international documentary association award. We haven’t shown it in America yet, so I was shocked to make that list of 25, standing right beside that mural. The timing was unbelievable.”

The immense pride of Alison and Lyra’s family in the journalist’s work is palpable on screen. McKee’s first book, Angels with Blue Faces, was about to be published when she was murdered, and she had been working on her planned second book, The Lost Boys.

“If LYRA brings people to her work, her writing and the person herself, that’s great. She didn’t sign a two-book deal with Faber & Faber for no reason! She was in the top 10 Ones to Watch on the Irish Times list. It’s an interesting time to release this film, because here we are again with no functioning Assembly in the North, watching an election be triggered. When she was killed, there was a political vacuum. We want a better life, as she would say.”

One aspect of LYRA that Alison values most is its incredible ability to educate others about the past, present and future of Northern Ireland from the eyes of a ‘Ceasefire Baby’.

“When we showed the film in Achill Island, which was amazing, we had a really big audience,” says the director. “There were people from Galway, Dublin, all over. They felt really comfortable asking us questions about the North that they didn’t know. They learned about the area through Lyra’s story. Her work, her life, her eyes. She touched on such important issues. That’s a real compliment. I think it’s also a tribute to Lyra’s knack for stories.

“She shined a light on intergenerational trauma, suicide and LGBTQ+ rights way before it was being spoken about. She wrote about Ballymurphy when she was about 17, way before it broke. Lyra had her finger on the pulse, and a curiosity. We’re both very similar in how nosy we are. We love talking to people. Most of our lunches, coffees, dinners together were about the lives of others.”

One of the film’s most heartbreaking moments traces the further loss of Lyra’s mother, Joan in 2020, just weeks before the first anniversary of Lyra’s death. “That bullet that killed Lyra took her mummy as well, it didn’t stop travelling, it killed Joan, the loss of her child killed her,” Lyra’s sister Nichola says in the film, somehow finding strength to keep pursuing justice.

“Joan was so brave,” Alison smiles, recalling the woman who adored Lyra with every fibre of her being. “She didn’t want to be filmed at the funeral, they asked for no cameras on her. We all decided that we were going to make this documentary, and she said, ‘I’ll talk to you, pet’. We went on a trip to receive an award on Lyra’s behalf, and that was the first thing I filmed. The second time I was shooting her, you can see how much weight Joan has lost. We were due to do another section about Lyra’s childhood, but she passed away. Joan got sick, and she wasn’t eating.

“Lyra was her main carer, because she had a prosthetic limb. I’ll never forget when she was laid out, and I came to the house when her remains were brought in. Lyra never looked her age anyway, but she just looked like a child in the coffin. The world’s media was at the front door, and I was sitting in the kitchen on my laptop trying to deal with people to keep them out of the way. Joan would wheel into the living room to sit beside Lyra, and stroke her hair. Otherwise, she’d be sitting at the kitchen table looking at this giant picture of her. Then she’d wheel back to Lyra again. It was surreal, the whole thing.”

Millar also recalls other aspects.

“There were some funny moments, too,” she reflects. “All of us were trying to fit Lyra’s glasses on her head but they wouldn’t go on. We were all putting them on and snapping bits of them by mistake, because she didn’t look like herself without her glasses. All the types of people Lyra had written about were there, because they had lost their loved ones in the conflict. Then that massive, mad funeral that had half the world at it. I’ve done so many screenings with the family, especially Nichola and [Lyra’s partner] Sara, at festivals. It’s amazing how I still look at them in awe that they can stand up and do a Q&A. Lyra had a lot of incredible women around her. I was lucky to have that. They always insist that you can do anything.”

LYRA cleverly interweaves the journalist’s passion and methodology for investigative journalism through each clip, as if we’re allowed inside her mind for a few moments. Her relentless dedication to the job, despite anxiety, is mind-boggling. It only shows her endless potential for helping victims of The Troubles, an irony so desperately sad it stops viewers in their tracks.

“Lyra saw stories at the end of her garden,” Alison reflects, earnestly. “The next generation of journalists can learn good practice from her, which is so needed. Intergenerational trauma was next door and Lyra pursued it. Universal themes come out of stories, no matter where they are. She believed that community-based journalism was key to getting people’s stories public. That investigative style where months of work is put in has either vanished, or it’s so badly funded that no one can do it. There’s never been a more important time for journalists to work. The amount of cover-ups and lies that we get pumped from various places; you really need good people to keep digging for the truth.

“That’s what she did. When she was 16, I was making a film about the closure of the Rape Crisis Centre in Belfast. It was my first film moving back to Belfast, and there she was. I thought she was on placement, and I asked her what school she went to. She said, ‘I’ve just won the Sky Journalist of the Year award, my name’s Lyra McKee’. That was me put in my place. Even at 16, she looked 12. That’s probably why at the start of the film, a woman screams, ‘A kid has just been shot in the head’. She never looked her age. She got ID’d three weeks before she was killed. She went to get her favourite strawberry cider at the bar of this media event at 29, and you could see her going mad looking for ID in her bag!”

What does Millar hope audiences gain from watching LYRA, as the North enters another run of elections in December and 2023 heralds 25 years of the Good Friday Agreement?

“My son is 24 and watched the film,” she says. “It’s great that it’s accessible to that generation. You want a younger community of people who feel the need to stop this from happening – who want to change things. Lyra’s message was always, ‘Brick walls aren’t made to keep you out, they’re there to see how badly you want it’. This work is about survival and overcoming barriers.

“I hope they enjoy spending time with her, ultimately. I don’t think we’ll ever meet anyone like Lyra again. She was one of a kind. I want people to learn about the North through her, because everything she did was 100 percent true, real and straight from the heart.”

• LYRA is in cinemas now.

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 14 Apr 23

TV premiere of LYRA documentary about life & death of Lyra McKee

- Film And TV

- 24 Jun 22

Channel 4 announce film on the life and death of Lyra McKee

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 21 Dec 25

My 2025: Corrina Brown - Best movie? " I really enjoyed Steve on Netflix"

- Film And TV

- 20 Dec 25

FILM OF THE WEEK: Avatar: Fire and Ash

- Film And TV

- 19 Dec 25