- Film And TV

- 30 Jul 24

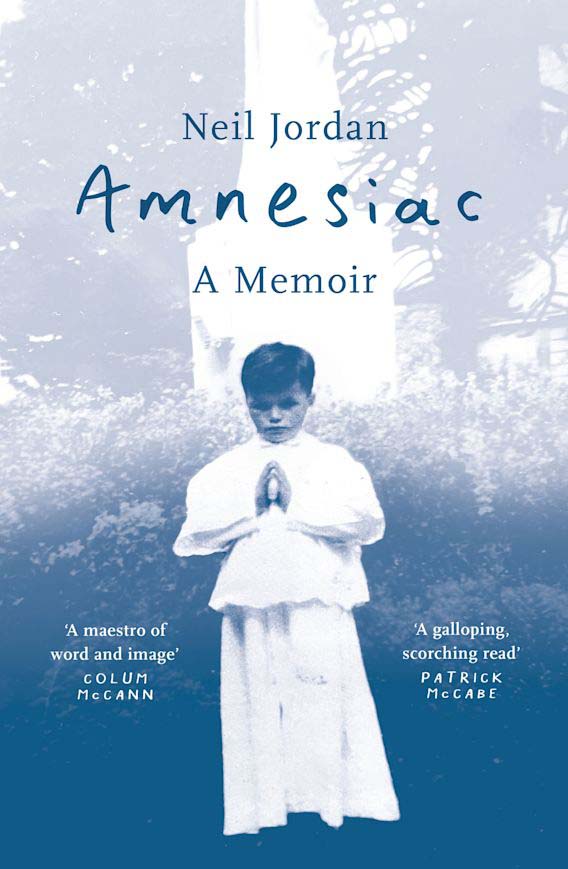

One of Ireland’s greatest ever filmmakers, Neil Jordan’s fascinating life and career are recounted in his superb new memoir, Amnesiac . He discusses his Dublin upbringing, Hollywood blockbusters, controversies, Tom Cruise, Stanley Kubrick, Francis Ford Coppola and more.

In these days of the Irish takeover of Hollywood, it’s interesting to think back about how much more exotic Irish success stories seemed in the ‘90s. Indeed, as a Tarantino-obsessed 17-year-old, I remember reading a book on the director and being delighted that Neil Jordan’s cult 1986 crime classic, Mona Lisa, was on a list of movies Tarantino considered the coolest ever. Along with his contemporary and college friend Jim Sheridan, Jordan brought Irish film to international attention throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s with movies like his 1982 debut Angel and 1992’s The Crying Game, which won him an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.

Naturally, Hollywood came calling and Jordan scored big with his 1994 adaptation of Anne Rice’s celebrated novel Interview With The Vampire, a blockbuster smash starring Tom Cruise, Brad Pitt and Kirsten Dunst in her debut screen performance. Elsewhere, the director enjoyed arthouse hits with a brace of adaptations of Pat McCabe novels, The Butcher Boy (1997) and Breakfast On Pluto (2005), the latter starring Cillian Murphy as the transgender Kitten Braden. In his compelling new memoir Amnesiac, Jordan reflects on his remarkable career, as well as recalling other episodes of his life, including his friendship with legendary director Stanley Kubrick, who initially got in contact after admiring Angel.

All of this and more were on the agenda, when I caught up with the softly spoken Jordan, now in his mid-seventies, on a sunny June day at the Haddington House hotel in Dun Laoghaire.

Your upbringing seemed quite bohemian, but maybe also lower middle class, or even working class.

No, my father was a teacher – you’re not working class if your father is a teacher. You can’t afford a car and that kind of thing! (laughs) My mother was working class in terms of her father being an electrician. All the brothers would have jobs and give you money. So we weren’t that kind of family.

Advertisement

But it didn’t seem particularly affluent.

No, it wasn’t affluent at all actually. We lived in Dollymount, but we didn’t have a TV until I was about 14. We didn’t have a car. I don’t know, maybe they were poor! But my father was a school inspector – you can’t be that poor when you’re a school inspector. It was on the edge of St Anne’s Estate and I went to school in St Paul’s in Raheny. It was a kind of middle class north Dublin existence really.

For someone who became a filmmaker, it didn’t seem particularly pop culture saturated.

I used to go to movies quite a bit, the Fairview cinema was down the way. But it wasn’t a pop culture environment at all actually. My father was an educator and the house was full of books, I do remember that. But no, it wasn’t pop culture. A lot of the references people have, in terms of TV series they saw at the time, I wouldn’t have. I talk to Pat McCabe and he’ll mention The Flowerpot Men and Postman Pat, and I’m like, ‘Okay, tell me about them Pat!’ (laughs) But I suppose the fact we didn’t have a television defined us.

Was it in adolescence that you fell in love with movies?

I was about 18 or 19. Or maybe when I was 14 or 15. The first movie where I ever remember thinking there was something different going on, was A Fistful Of Dollars, the Sergio Leone film. And it was mainly the soundtrack actually. We used to all get the bus into town, see movies, then walk home and get into a scrap afterwards!

As you detail in the book, there was also this bizarre element where you were being stalked by a paedophile.

Advertisement

Wasn’t everyone?!

It seemed to be a part of the landscape of society at the time.

Totally. There is that story about James Joyce, where he’s on Booterstown Strand, and a man approaches him with bottle green eyes. It was as a similar kind of thing – it’s actually one of the stories in Dubliners. But when my sister read that section in my book, she went, ‘Oh, I had my own paedophile too!’ It’s not like the guy ever got me into the shower or anything. I wasn’t into football or anything, so rather than hang around with boys, I used to have girlfriends. So when I was going through my experiences, I’d go, ‘Okay, I was in this relationship for a year and half.’ But then I thought, ‘Well, the most constant presence in my life was this weird guy who used to follow me around!’ And that’s why I wrote that chapter.

Was that whole period uncomfortable?

Deeply. But then you feel sorry for the guy in a way, it’s very strange. There’s just a very weird, kind of lost idea of sexuality going on there. Obviously the guy was gay. He used to pretend he liked my sister, but I knew.

When you came to make your first movie, Angel, were you more inspired by European movies, as opposed to the New Hollywood?

Well, I was inspired by two things. One, by Hollywood b-movies, with directors like Nicholas Ray and films like Gun Crazy. But the main thing that influenced me was German cinema and people like Wim Wenders and Fassbinder. Not so much Herzog. When I began thinking about movies, suddenly there was this explosion of films out of Germany, and a lot of them used genre in an interesting way. Fassbinder would make a Douglas Sirk-ian melodrama. Wim Wenders would make a movie like The American Friend, which was kind of film noir. That was my generation.

Advertisement

Angel was really well received when it came out.

It made a reputation for itself. But it was very awkward because there was this big argument over it here at the time.

I wasn’t particularly aware of that before I read the book.

You wouldn’t have been. It was a very different climate. Everybody was making films and it was very unionised. There was a presumption that you had to be a trainee or something like that. I remember saying to one guy, who was a director, that I was going to a make a movie. He was going, ‘No you’re not!’ Because I was a writer. So it caused this really stupid controversy. When it was about to be sold in Cannes to all these different territories, people were giving out about the Film Board and they wanted to see every contract. But it was successful in its reputation.

Writing is more of an internal art-form, so how did you find the step-up to directing on a movie set?

I just knew what I wanted so see through the camera. I wasn’t that well-versed in the language of cinema, cos I hadn’t gone to film school or anything. But I did know what I wanted to see very clearly. I think that carried me through.

Advertisement

You then made The Company Of Wolves and subsequently Mona Lisa, which is a big favourite of mine.

Well, Mona Lisa was big all over the place, as was The Company Of Wolves. But I didn’t realise how successful Mona Lisa was gonna be. I’d done Angel and I thought I was lucky to get to make a film. But then I made The Company Of Wolves, which was successful throughout Europe, France and Spain. Not so much in America, although it was released there. But Mona Lisa was a big success. Bob Hoskins won Best Actor for it at Cannes and he was also nominated for an Oscar, so it did really well.

I’ve seen Mona Lisa on lists of Quentin Tarantino’s favourite movies.

Quentin likes Mona Lisa? I’ll tell you what I did in that. I kind of had the people speak in a way that was miles from what you think a crime movie would be. There were long digressions where they’d be talking about angels and books, and this and that. Michael Caine spoke like a Cecil B. DeMille character in that strip joint he ran. So maybe that’s why Quentin liked it.

Have you met Tarantino?

Yeah, I met him. He’s good. I met him on a plane – we were going to Busan and just passed each other. I mean, I haven’t had a real conversation with him, but we’ve been in the same vicinity!

Did Stanley Kubrick hire Anton Furst as production designer for Full Metal Jacket on the back of The Company Of Wolves?

Advertisement

Yeah, Stanley saw that film and asked me to introduce him to Anton, which I did. Anton was nearly driven insane on Full Metal Jacket, but it’s a great movie.

I remember when I interviewed Gaspar Noe, we ended up discussing our favourite Kubrick film and I went for Full Metal Jacket.

It’s great and it all happens in real time. If you watch it again, it all happens as night is falling in Hue or wherever.

Anton Furst seemed like an extravagantly talented person.

When I made The Company Of Wolves, he’d only done one movie, which was called An Unsuitable Job For A Woman, which was a black and white road movie, directed by Chris Petit. Anton was very frustrated. He was a huge talent, a beautiful illustrator. He’d done some set-dressing work with Ridley Scott, I think on Alien, but he hadn’t really made a movie. When we made The Company Of Wolves together, I suppose he shone. Anton was an art student, he came out of the Royal College of Art and he’d set up a laser company in Pinewood. I don’t know what that was! But he was totally well versed in German expression and so on. He was like a brilliant art student. His production design for Tim Burton’s Batman movie was absolute genius as well. Well, he won an Oscar for that. Tragically, Anton ultimately died by suicide.

Was he a troubled guy when you knew him?

Anton was a dear friend of mine. He used to come over here and stay with me in Bray, and when I went to Los Angeles, I’d see him. I’d see him in New York. He was suddenly propelled into the front end of Hollywood. He was getting increasingly paranoid, I could see. Somebody had hired him because they wanted to make a movie with Michael Jackson, who was the biggest star on the planet at the time. The conversations were becoming more and more convoluted. So he must have gotten terribly distressed, and he jumped off the top of Cedars Sinai hospital. It was awful.

Advertisement

There were a few notable omissions in the book – for example, you didn’t talk about working with Robert De Niro on We’re No Angels.

Well, I didn’t want to. Because nobody sees that movie anyway! (laughs) They’re doing a laser disc of the movie at the moment, and there was another cut of that film we made. The producer, a guy called Art Linson, he liked the more extravagant performances of De Niro and kept pushing for those to be included. I kind of think it ruined Bob’s performance, and I just didn’t want to get into that.

What was De Niro like to work with?

He was delightful. Lovely guy, very intense. He has a very simple approach to acting, which is, it has to be real or it’s not there. What he’s responding to has to be real. So if he’s reacting to an elephant charging towards him, the best thing to do is get an elephant.

When The Crying Game became such a big hit, did you start to get a lot of offers from Hollywood?

No, the minute I made a movie I was being offered things from Hollywood. Even after I made Mona Lisa, that was happening. So when The Crying Game became this big success, as you say, people would react like it was my first movie. I’d had this other life entirely. But I’d been through the Hollywood system, let’s put it that way, and you’ve got to learn how to make it work for you. The only way you learn is by doing it. So when I came to make Interview With The Vampire, I kind of knew enough to set it up to make it work for me. I could get David Geffen, the producer, to guarantee me I could make it the way I’d make an independent film. When you see the Marvel movies, what they do nowadays is hire very young directors. Some of them I’m sure are very talented, but the reason they hire young directors is because they can steer them. They don’t want somebody who’s totally independent, unless it’s Kevin Feige.

Advertisement

The Crying Game

The Crying GameAfter seeing and admiring Angel, Stanley Kubrick got in touch and two of you became friends. It was very interesting in the book, the way you describe him approaching everything through images. Do you think that was his way into storytelling?

Well, the thing is, when I began talking to him, he was interested in talking to me because I was a writer. So I was talking to him about a lot of theoretical books about painting and visual art, and I realised he hadn’t read them. There was a guy called Walter Benjamin, who wrote a book called The Work Of Art In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction, a seminal text from the ‘30s. I was surprised Stanley hadn’t read that. If you talked to him about Ken Auletta, Raphael or Turner, he would know everything. But with that stuff, it was completely different. I mean, look at the novel he chose to make, Barry Lyndon – it’s not one of the great novels of that era. Tom Jones is a far better book.

You mention in the book that Kubrick seemed interested in moving to Bray.

He phoned me up and asked me. He pretended it was a friend of his who was a multi-millionaire, who was looking for a place in Ireland. Maybe it was to do with the artist tax breaks. He gave me a very precise description of the place this friend of his needed. It had to be on a promontory, facing the sea (laughs). I’d go, ‘Who is this guy?’ And he’d go, ‘It’s just a friend of mine!’ Anyway, he would never have left his home in England.

Kubrick’s influence on culture is just unbelievable.

Do you think so?

Advertisement

I do – I see it everywhere. Not just movies, but also books, music, video games...

I often think it’s a bit sad. Because around the time when Kubrick came to dominate the scene, was when European cinema was kind of vanishing from people of your generation. I know where you’re coming from.

For my generation in the ‘90s, our filmmakers were the likes of Tarantino, David Fincher and Paul Thomas Anderson. They would have championed Godard and Truffaut to a certain extent, but they were heavily New Hollywood-influence.

So I guess, rather than being interested in Fellini or Ingmar Bergman, the young film enthusiasts became interested in this rigorous, almost mechanistic version of cinema, which Stanley kind of invented in a way. I didn’t think Eyes Wide Shut was great.

I think it’s a total classic.

You think Eyes Wide Shut is a classic? Okay! I just thought the orgy scenes were absurd. He died shortly before it was released. I’m sure if he’d lived, he’d have done something else with it.

In Amnesiac, you talk about how on Interview With The Vampire, you weren’t initially sure if Tom Cruise was right for the movie.

Advertisement

I wasn’t. For one thing, the character of Lestat is described as tall and blonde. Tom is small with dark hair. But the second time I met him, I thought that’s exactly what the part needed.

In the book, you talk about waiting for him on the balcony at his house, and realising he was out there running in the Hollywood hills. Like Lestat, he was away from people.

Well, he lived in Brentwood and I think he still does. He’s an incredibly fit guy, but he hasn’t got a naturally athletic body the way, say, Brad Pitt or Chris Hemsworth does. Tom is not that natural physical athlete. Everything he’s got, you feel he’s earned.

Does he come with bells and whistles?

No. I mean, there are bells and whistles to get through to him, but once he’s there, he’s there to work.

Interview with a Vampire

Interview with a VampireAdvertisement

I was recently talking to Duff McKagan of Guns N’ Roses, who covered ‘Sympathy For The Devil’ for the end credits of Interview With The Vampire.

That was a weird one. Guns N’ Roses were on Geffen Records, David Geffen said, ‘I have this great idea - Guns N’ Roses are going to reassemble to record ‘Sympathy For The Devil’.’ And once they do that, you have to use it, you know? Maybe the Rolling Stones version would have been better!

Would you like to have done more Hollywood blockbusters?

Well, I came back and did Michael Collins. I could have stayed and done that. Maybe I should have. But I had kids here. Even if I had stayed and done that, I don’t know anyone who’s had real success doing that, apart from Quentin Tarantino.

And Christopher Nolan.

But he’s much younger than me, and that’s the only kind of movie he makes. The rest of my generation – Brian De Palma, Stephen Frears, Doug Liman – in terms of Hollywood, I don’t know if they’ve had that really rewarding creative life. I’d end up doing The Lion King or something. Anyone can do that – who directed The Lion King?!

There’s been some controversy about the book over the Garret Fitzgerald anecdote. Where he talks about getting paid by Warners for a positive review of Michael Collins. It’s absolutely bizarre, because the way it’s presented in the book, it seems fairly obvious that Fitzgerald is joking.

Advertisement

Well, I thought it was funny and that’s why I put it in the book. That guy who wrote the Guardian piece kind of misinterpreted. For one thing, Garret Fitzgerald didn’t say he had been paid, he said, ‘I must send them an invoice’, which could have been a joke or not. It seemed obviously a joke to me. It was. Some people love to stir shit! I was in San Francisco last New Year’s and visited Francis Ford Coppola’s cafe.

Did you ever meet him?

Yeah, I’ve met him. I’ve been in the cafe as well, it’s in that triangular building. He had a magazine called Zoetrope, and some of the things in this memoir were published in it years ago. About 10 years ago, he sent me the script for Megalopolis, and he wanted comments on and all that sort of stuff. I know it’s coming out, but I haven’t seen it. Have you?

I haven’t although I’m fascinated to, as Apocalypse Now is probably my favourite movie of all time. Finally, during lockdown in 2020, I read Oliver Stone’s memoir which was absolutely compelling. He mentions attending a film festival in Dublin, meeting you and being absolutely delighted you were a fan of Salvador.

Did Oliver say that? I really love that movie. And it’s James Woods’ best performance before he turned into a fucking nutcase!

• Amnesiac is out now.