- Film And TV

- 18 Jan 22

It was the mega-hit that rose up from the depths to catch everyone unawares – Netflix included. But Hot Press’s Television Series of the Year was more than just ultra-violent entertainment. It spoke to our present day anxieties about class, privilege and being menaced by giant talking dolls, says Ed Power.

A giant doll, painted in child-friendly primary colours, sings nonsense verse. A man in a green tracksuit suffers a breakdown trying to prise umbrella-shaped candy from its case. A smoking corpse flops down a slide, leaving a slippery, bloodied trail.

These are some of the images that have made Netflix’s Squid Game not only the most talked and tweeted about TV series of the year, but also one of the cultural phenomena of the past 12 months. Arguably not since the glory days of Game Of Thrones or the early seasons of Stranger Things has a show so emphatically taken up real estate in the world’s frontal lobe.

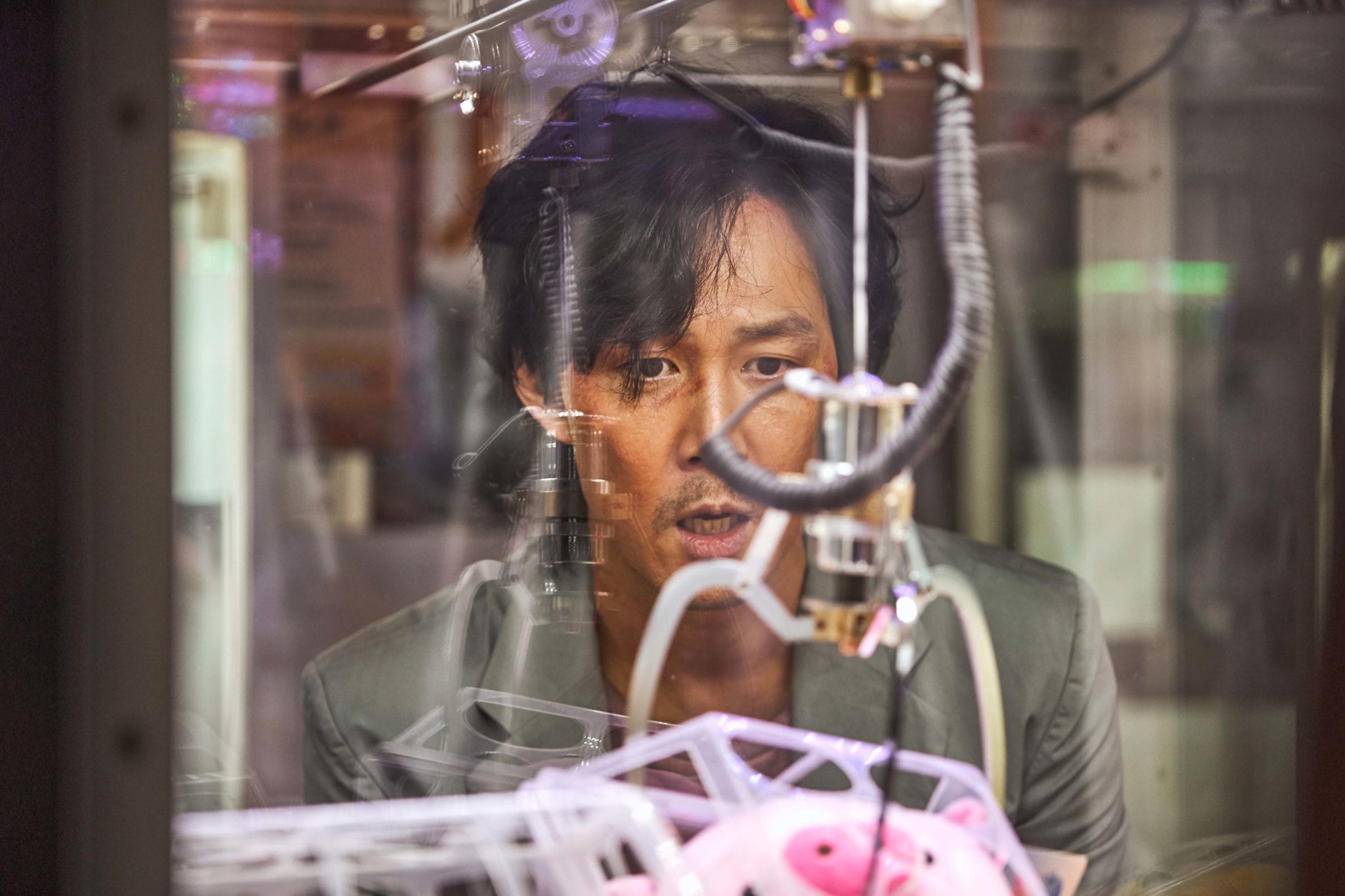

Squid Game’s appeal rests to a huge degree in its simplicity. In modern day Seoul, middle-aged Seong Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae), down on his luck and in dire financial straits, signs up for a contest in which he competes in a sequence of challenges. Win and he walks away with a fortune. Lose and he dies by machine gun.

The featured games are the stuff of playgrounds across the world. The first is “red light, green light”, with the aforementioned giant doll singing a trilling verse. When she ceases warbling, anyone still moving is brutally gunned down. Later, comes a challenge involving dalgona candy – a Korean speciality known for its waxy consistency.

Advertisement

The contestants must prise an etched silhouette from out of the candy without causing it to crack. Succeed and they have a sweet treat. Fail and a red-garbed guard dressed like a refugee from Patrick McGoohan’s surrealist 1960s thriller The Prisoner will shoot them in the face (hence that body slipping down the slide).

Schoolyard games bring us back to the innocence of childhood. But in Squid Game they are combined with gaudy violence and with a desperate desire to improve one’s social status, via that huge payday. It’s a quixotic mix and one audiences have responded to in blockbuster numbers since the nine-episode season was quietly launched by Netflix on September 17.

Its success is truly jaw-dropping. Up to this year, Netflix’s biggest hit was Shonda Rhimes’s Downton pastiche Bridgerton, which subscribers had watched for a cumulative 625 million hours. Squid Game blew straight through that figure to clock up 1.65 billion hours by mid-October.

Nobody was more surprised than Netflix. The company’s chief content officer, Ted Sarandos, said he never anticipated Squid Game taking off to the degree it did.

“I can’t say that we had the same eyeball on it that it was going to be the biggest title in our history around the world,” Sarandos told investors. “Sometimes you think you have lightning in a bottle and you’re wrong. And then you have a really great Korean show that happens to be lightning in a bottle for the rest of the world.”

In addition to the simplicity of the premise, Squid Game resonates because it speaks to the growing inequality between rich and poor around the world. Seong Gi-hun is a divorced father and gambling addict who signs up to Squid Game in the desperate hope that winning big will help him keep his family together. A investment banker teetering on bankruptcy, a gangster with debts, a migrant from Pakistan and a refugee from North Korea are among the other participants – all despairing individuals driven to the brink by circumstances generally outside their control.

Obviously few of us are investment bankers facing bankruptcy or escapees from North Korea. And yet these stories resonate – as does the fact the games are played for the benefit of mega-bucks VIPs in golden masks. In our day to day lives, it can feel our blood and sweat is merely for the benefit of the super-wealthy. That life is just one long session of “red light, green light”.

Advertisement

One person who certainly knows that feeling of having a boot pressed to his neck is series creator Hwang Dong-hyuk. He was inspired to write Squid Game after experiencing financial deprivation following the 2009 global crash.

“I was very financially straitened because my mother retired from the company she was working for. There was a film I was working on but we failed to get finance. So I couldn’t work for about a year,” he told the Guardian. “We had to take out loans – my mother, myself and my grandmother.”

To take his mind off money he turned to manga comics. Which was how he came up with the idea of trial by combat for people facing financial oblivion. A sort of Hunger Games meets The Price Is Right via the Bushtucker Trials on I’m A Celebrity… Get Me Out Of Here!

Hwang meanwhile took refuge in Seoul’s comic book culture.

“I read Battle Royal and Liar Game and other survival game comics. I related to the people in them, who were desperate for money and success. That was a low point in my life. If there was a survival game like these in reality, I wondered, would I join it to make money for my family? I realised that, since I was a film-maker, I could put my own touch to these kinds of stories so I started on the script.”

“Squid Game is not really a show about survival games,” agreed lead actor Lee Jung-jae when talking to the New York Times. “It’s about people. I think we pose questions to ourselves as we watch the show: Have I been forgetting anything that I should never lose sight of, as a human being? Was there anybody who needed my help, but I was unaware of them? Should I have helped them? I think if they re-watch the series, the audience will be able to notice more of these subtle elements.”