- Film And TV

- 06 Nov 23

Susanna Fogel : "The experience of being a woman always contains a base level of fear"

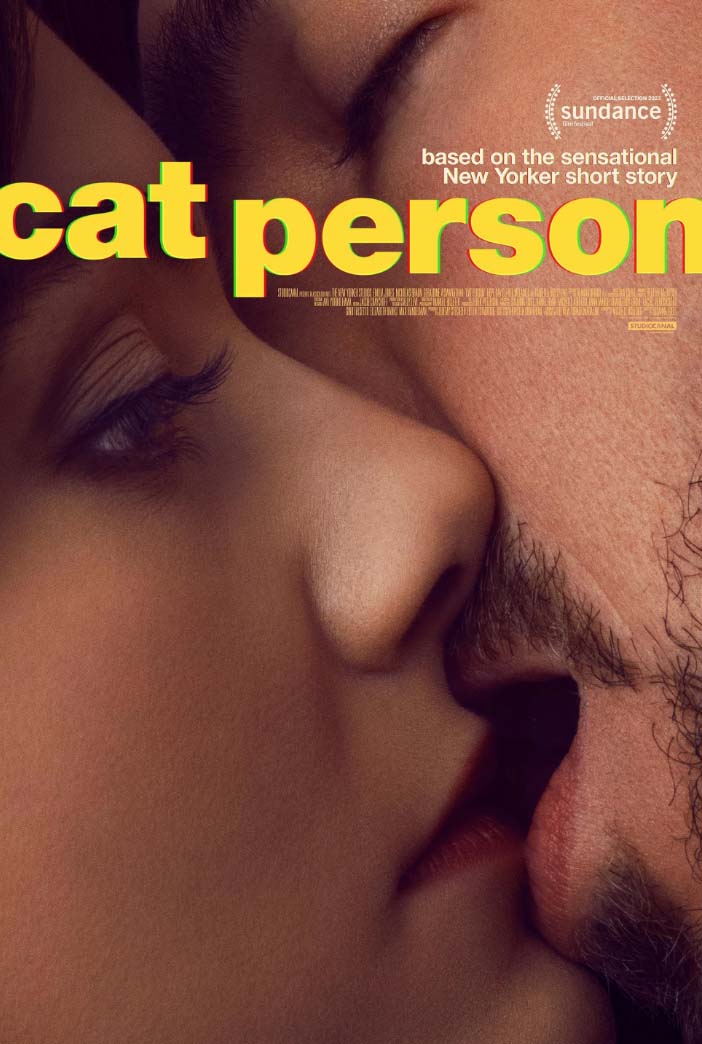

Cat Person looks at the always contentious issue of consent from some important new angles. Writer-director Susanna Fogel talks to Roe McDermott about why she felt compelled to make the film and some of the perplexing reactions to it.

In 2017, a short story published in the New Yorker made the internet lose its mind. In Cat Person, written by Kristen Roupenian, 20 -year-old college student Margot falls into a flirtation with an older man named Robert and as their relationship develops, Margot’s perception of the power dynamic between them seems to endlessly shift. In one moment, Margot sees herself as a beautiful, smart, desirable woman who renders Robert into a bumbling loser grateful for her attention. At other times, Margot feels immature around him, and occasionally afraid, knowing that this man with insecurities and a jealous streak could, at any point, lash out and hurt her.

This fluctuation between empowerment and disempowerment extends to sex, too. Margot consents to sex with Robert - but at times feels uncomfortable and even afraid, but goes along with the unpleasurable, unfulfilling encounter because it seems easier than stopping it. Robert never notices her ambivalence or lack of enthusiasm.

This idea that two people could have completely different experiences of the same encounter was what appealed to director Susannah Fogel, known for co-writing the gloriously fresh and funny friendship comedy Booksmart. Fogel was intrigued not just by the story, but also the intense reactions it provoked, which divided people in their determination to make the story about one clear violation or villain.

”It’s easier for us to speak as a culture publicly about extreme issues of consent, where there’s an assault or a clear ‘no’ that’s overridden,” says Fogel. “What the story really showed was how people reacted strongly to all the grey areas.”

One thing the film shows is the gap between a sexist rape culture, in which women are still slut-shamed for expressing sexual desires, and current discourse around consent, which puts the onus on women to know exactly what they want, ask for it clearly, reject things clearly, and still manage both men’s emotions and the fear of what happens if a man doesn’t take a rejection well. In a soon-to-be iconic, much-studied and discussed scene, Margot and Robert have sex, while a disassociated version of Margot watches herself, wondering why she’s going along with an encounter she doesn’t really want and isn’t enjoying.

”Everyone’s confused,” agrees Fogel. “We don’t have a language for talking about ambiguity and grey areas, and women are completely overburdened from their teens, from the age of consent, to be fully aware of what they want through an entire encounter and say what they want - but I don’t know many people who don’t have a much more dynamic mindset. Also, interactions are fluid and it can be about safety, but it can also be about placating, you know?

”It’s not that the only reason women don’t say ‘no’ is that they’re afraid for their safety. Sometimes it’s just not worth having to de-escalate an annoying conflict with a victimised man, or it’s not worth dealing with an encounter that’s hostile with a person you don’t know that well. It’s all of it, and the more we can talk about these things head on, the better.”

For Fogel, showing that Margot can want Robert’s attention, but not want to have sex with him, shows the complexity of navigating the world for women, who are taught to find their value in their looks and sexual desirability, but are also told not to use their sexual desirability, and to never be a prude or a tease.

”I have a very close friend who is an adolescent psychiatrist,” says the director, “and she saw the movie. She said it gave her the language to talk to one of her patients who kept getting in sexual situations that she didn’t want to be in. My friend said, ‘Okay, so I saw this movie and let me see if I can analyse what’s going on. You kind of want the validation because you walk around feeling invalidated. You kind of want the attention that feels really good. But when it comes to an actual in-person encounter, you’re not comfortable. So you cut it off, but you cut it off in a coy flirty way that’s not always perceived as a ‘no’. And then you end up in a sexual situation you don’t want to be in, and feeling some shame for having brought it on.’ The girl just said, ‘Yes, that’s exactly what I do.’”

In Cat Person, cinema itself plays a big role in how Margot and Robert both come to understand sex and relationships. Robert idolises Harrison Ford, and a montage of scenes from films like Star Wars and Indiana Jones show the romantic role-models Robert and men his age grew up with: arrogant male heroes who didn’t take ‘no’ for an answer, pushed women against walls and kissed them without permission - and got the girl. Porn is also obviously an influence on his sexual performance, which is vigorous and thoroughly disconnected.

For Margot, she often imagines how an encounter with a man will go in terms of movie tropes - at one moment, she’s the lead in a rom-com, in another she’s the Final Girl in a horror movie, in another she’s the victim in a true crime documentary. For Fogel, this speaks to women’s constant navigation of the world.

”The experience of being a woman always contains a base level of fear, because we’re we know we’re smaller and vulnerable. Period,” she says. “So that fear, and also years and years of seeing movies about women being victimised, mean those images are just in your head. But also, for most women, they’re not walking around the world in a horror movie. They also have the novel fun conversations with their friends. They also watch romantic movies and see sweeping stories of love. So women are constantly taking the data they’re getting and figuring out what the story is at any given moment.

“The most baffling reaction I’ve gotten from male critics is that this movie doesn’t know what genre it is. Is it scary? Is it funny? Is it romantic? Which is it? They have to decide which it is. No. Women live in the world without knowing which it is. That’s the point.”

Cat Person is in cinemas now.

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 21 Dec 25

My 2025: Corrina Brown - Best movie? " I really enjoyed Steve on Netflix"

- Film And TV

- 20 Dec 25

FILM OF THE WEEK: Avatar: Fire and Ash

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 19 Dec 25

Teaser trailer released for James Stewart biopic filmed in West Cork

- Film And TV

- 18 Dec 25

Final trailer released for Anaconda

- Film And TV

- 18 Dec 25

RTÉ to celebrate 100 years of broadcasting in 2026

- Film And TV

- 18 Dec 25