- Lifestyle & Sports

- 12 Sep 24

Riccardo Dwyer talks to a range of academics to understand how AI is currently impacting third level education – and the effects it might have in the future.

Everyone’s talking about artificial intelligence. It’s here to take our jobs and fastrack the downfall of humanity. Haven’t you seen 2001: A Space Odyssey, iRobot or all six Terminator films? Arnie won’t always be around to save us, you know.

The subject is particularly controversial in third level education, with much of the discourse centred around students’ use of popular Generative AI tool ChatGPT.

A survey in the UK conducted by the Higher Education Policy Institute earlier this year found that 53% of students used generative AI on graded assignments. Other surveys in the US and elsewhere have revealed similar statistics, with research conducted by Study.com in 2023 suggesting the percentage of students using ChatGPT on their homework is as high as 89%.

It’s not difficult to see why. You essentially feed it a prompt and it spits back convincing-looking answers, including entire essays, in seconds. Students – tired, under pressure and let’s face it, susceptible to laziness and distractions – make an obvious clientele.

As a new academic year looms, educators across various disciplines are rightly concerned. But how exactly does this stuff work? What makes it a threat to academic integrity? And should we, considering it’s not going anywhere soon, even embrace it?

Advertisement

“There’s a war raging in classrooms, because you can’t really ban students from using ChatGPT,” says Dr Arash Joorabchi, course director of natural language processing at University of Limerick, where ChatGPT and other generative models play an important role. “One of the biggest problems is what we call ‘Hallucinations’. The system is giving you what seem like eloquent answers, but a lot of the information just isn’t true, which is an issue when students are trying to learn.”

“There’s an illusion of intelligence,” UL colleague and module leader Dr Eoin Grua adds. “It’s essentially a very complex equation trying to predict which word goes after which. The model is scraping a load of data and coming up with predicted sentences. A common misconception is people thinking they can use ChatGPT instead of Google. But it just generates text, without caring whether it’s true or not."

“Therefore, in the sciences, it’s much easier to detect usage, as your answer is either right or wrong," continues Dr. Joorabchi. "If we’re talking about writing code or programming, it’s really easy for a lecturer to realise that a student has used a tool to produce that code too. When it comes to humanities, it becomes a greater challenge, as things are more subjective.”

Enter Dan Murphy. Perhaps best known to readers as the lead vocalist with Limerick outfit Hermitage Green, he also works at the Institute of Contemporary Music Performance in London as a tutor and module leader on their BA in Creative Musicianship.

After witnessing a rise in the use of AI in both professional settings and his classrooms, the artist and educator decided to run his own experiment.

Dan Murphy

Dan MurphyAdvertisement

“As you’d imagine, students are always looking for loopholes and shortcuts to get around assessments,” Murphy says. “We have safeguards in place that help detect if a student has used AI, but the thing about this conversation is that it’s all evolving so quickly. As a research project, I used AI to write a couple of songs, before having an assessor mark them. I used Loudly to generate tracks and ChatGPT for the lyrics and accompanying commentary.

“The songs themselves got 72%, which is a distinction, while the essay received 68%. I was shocked at how easy it was to drum up the whole thing. I thought the lyrics were hit and miss, but some of the tracks were really convincing. The results speak for themselves: the assessor didn’t pick up on it, which sums up where this is at.”

Murphy teases out the subject further.

“It’s pretty much inevitable that we’re going to marry with this technology,” he continues. “Writers will use it to generate ideas, or to get out of a dead-end if they’re stuck with writer’s block. I would encourage discourse around it. One of the building blocks of education is getting students to reflect on why they’re doing something. If you’re using AI to take shortcuts, you’re going to diminish your ability to learn and become a better version of yourself.

“You might not get caught, and sail through your degree by using ChatGPT, but you’re going to be a pretty complacent professional when you come out the other end.”

Diligence and honour among students is an obvious solution – if they don’t use AI, there’s no real issue. As Murphy notes, it’s their future that’s at stake. That said, the easy option is tempting when €2 Jager Bombs are on offer at the Union Bar and you’ve got an unfinished assignment lingering.

So what can teachers do to try and stop this from getting out of hand?

Advertisement

“It’s something people have been worrying about,” says Joel Walmsley, lecturer in Philosophy at UCC. “I’m pleased in a sense. It means educators have to think carefully about the kinds of assignments we’re providing. After all, if you assign the sort of essay that could be written well by a robot, maybe you didn’t assign a very good essay.

"Some have gone back to basics, placing more of an emphasis on written examinations under controlled conditions. Other approaches have included assignments which require self-reflective writing, or comparative pieces between highly unusual perspectives which ChatGPT wouldn’t be good at. You can also assign things based on recent events, like news, or other things that go beyond its training data set.”

Walmsley, who teaches a module on the philosophy of artificial intelligence, takes it a step further, getting students to incorporate generative AI into their assignments.

“One advantage is that this helps them learn how it actually works,” he explains. “Part of our job as educators is teaching students how to use new tools. It’s also difficult to cheat on an essay by using ChatGPT when the essay requires you to use ChatGPT. They’re supposed to explain why they chose certain prompts and give an analysis of the responses they get, using their texts and the concepts we’ve discussed in class. As a result, I’ve had essays from students which have been really original, creative and interesting.”

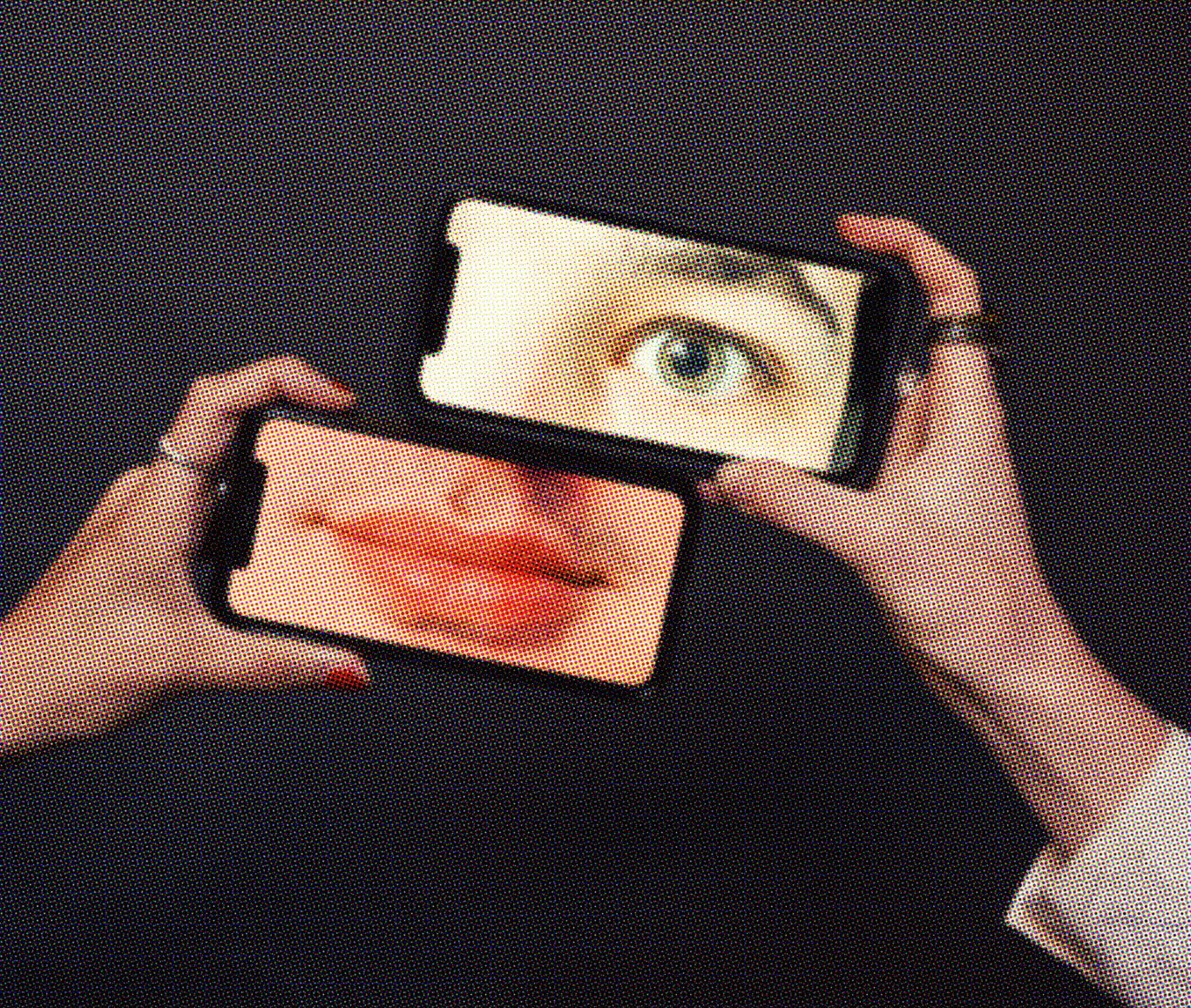

Photo: Miguel Ruiz

Photo: Miguel RuizThere’s also potential applications for generative AI as a useful supplementary study tool, as long as users avoid over-dependence.

Advertisement

“There are some things that ChatGPT is really good for, like brainstorming,” he suggests. “If you’re procrastinating, you can throw a few prompts into ChatGPT and generate ideas. It’s quite good for boring mechanical things too, like doing up bibliographies. I’d also advise students to be cautious about using it like a search engine.

“What it’s really doing is showing you what an answer to your question might look like. You’d have to fact check everything regardless. I find it easy to tell when an essay has been written by ChatGPT. There are various characteristics in the way that it phrases its answers, the expressions it uses. It writes very formulaic prose.”

Walmsley offers some final thoughts.

“But if a student has found a way to use AI to do something really cool, then I want to know how,” he says. “If you’re thinking of using AI, I recommend checking with a lecturer to see if it’s permissible. Explain exactly what you want to do and why, and use standard citation practices to give credit where it’s due.

“If we’re honest and open about it, but also cautious, then I’m inclined to think we can get people to approach it in the right way.”

Read the full Student Special in the current issue of Hot Press – out now: