- Lifestyle & Sports

- 21 Nov 23

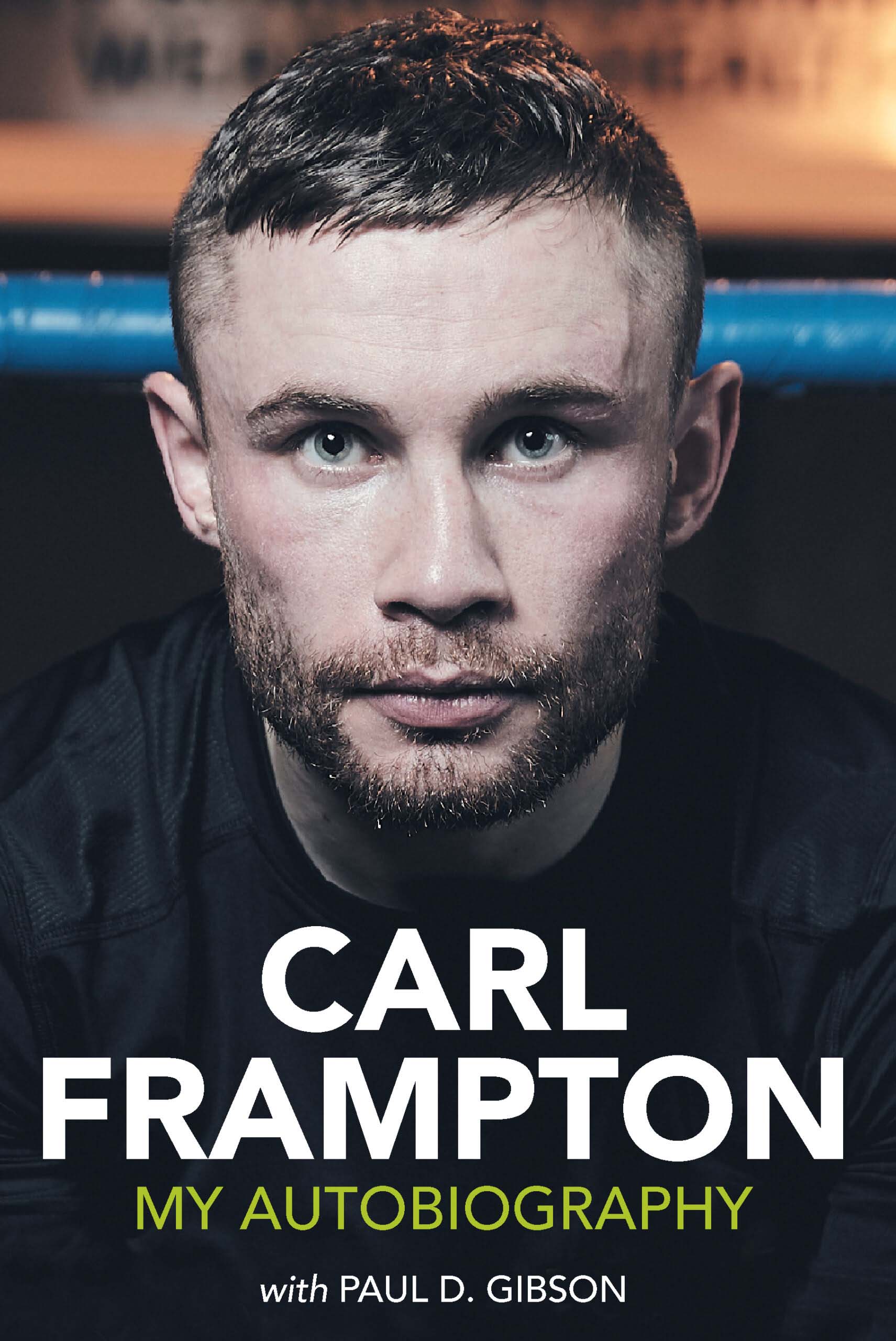

Renowned boxer Carl Frampton discusses his new memoir, becoming a world champion, falling out with Barry McGuigan and epic entrance songs.

Carl Frampton was born to box, something which Billy McKee, founder and head coach of the Midland Amateur Boxing Club in Belfast, immediately spotted when the future two weight world champion wandered into his gym, aged seven.

The kid could punch straight, hold up his hands, move, take punches and keep going; in addition, he possessed razor-sharp reflexes, agility and co-ordination. He made his ring debut that same year, kickstarting a three-decade glittering career in boxing. One of the most popular fighters in the history of Irish prize fighting, his career was star-studded. He held the IBF super-bantamweight and WBA featherweight world titles and was The Ring magazine Fighter of the Year in 2016.

No ordinary man, yet the person who meets Hot Press on a quiet Friday afternoon in Dublin’s Brooks Hotel appears just that – unassuming, down to earth, quick to banter. Learning I’m from Mullingar, he asks after his old friend and rival from their amateur days, David Oliver Joyce.

We chat about music and he tells me about the ring walk songs he chose during his career. They are an eclectic mix: James Brown’s ‘The Boss’; Florence & The Machine’s ‘Spectrum’; Jackie Wilson’s ‘Your Love Keeps Lifting Me Higher And Higher; Bjork’s ‘It’s Oh So Quiet’ and more.

Frampton is doing the media rounds to promote his autobiography and will appear on The Late Late Show later, before driving back to Belfast to bring his young son to football training in the morning. Family is everything to him. He speaks about his wife Christine and children – Carla, Rossa and baby Mila – regularly, in addition to tenderly talking about his parents and late grandfather.

Advertisement

His eponymous autobiography details his working-class roots in Tiger’s Bay, North Belfast. His depiction of the sectarian divide is erudite and enlightening, while his descriptions of his professional fights are illuminating even to the non-boxing fan. But let’s back up a little and ponder Carl clambering into the ring at the rowdy and smoke-filled Causeway Hotel in Portstewart, aged just seven.

“I was the only boxer that the Midland Boxing Club brought up – they must have saw a bit of talent, you know what I mean?” Carl laughs. “Look, I was good at sports, I was half-decent at football. I played a wee bit of rugby at school, I was a half-decent scrum-half, size let me down a bit. But I played everything. I was alright at table-tennis, I could play badminton if I wanted to, not at any level, but I was competent.

“I was an all-around sports person, but boxing was definitely the one for me. Billy’s perspective was, ‘When you have a seven-year-old kid, you’re not expecting Muhammad Ali. What you’re looking for is someone who can listen to instructions. The reaction when they get a punch in the mouth is important, because if he throws back rather than crying or turning away, then you might have something to work with.’”

MIdland Boxing Club

Carl lights up when he recalls those early days.

“I loved it,” he enthuses. “And the reason I loved it was because I was quiet. I was a shy kid that didn’t like conflict – if anybody raised their voice on the street, I would shy away. But the guys who I was afraid of on the street, they all at some point ended up in the boxing club and I used to beat the shite out of them. I liked that macho element of it. And I suppose being better than the next man.”

Advertisement

Carl grew up a stone’s throw from The Midland Boxing Club in 1990s North Belfast, in an interface area (zones where segregated Nationalist and Unionist residential areas meet). Boxing was a sport dominated by Catholics – Holy Family, Star, Belfast, Newington and the Dockers are all within a half-mile radius of one another and are all Catholic. I imagine it was more than a tad intimidating when you went there to fight.

“Not really” he says. “As I got older, no. I would feel comfortable boxing in a Provie drinking den in the middle of the Falls Road. I’ve boxed in The Felons, which was a republican club, I’ve boxed in the PD and these places. I’ve been up there at funerals of my wife’s family. It’s almost like I get a free pass. I can go anywhere I want really in the city, which is nice.”

TOP OF THE WORLD

Carl’s wife Christine is a Catholic girl from Poleglass in west Belfast. As with his former manager and mentor Barry McGuigan before him, Frampton is regarded as a symbol of hope and unity across both sides of the sectarian divide in Northern Ireland. However, Frampton and McGuigan’s personal and professional relationship went south, with the boxer suing the manager for withheld earnings, and the manager issuing a counter claim. The case was settled without judgement.

The papers will be full of the poignant story the morning after Carl talks about it on The Late Late Show, stating, “I understand that Barry is a hero to many people. He was a hero to me. But if you read this book, and still think he is a hero, you need to give your head a wobble.”

The boxer not getting his rightful share of the purse is an age-old story in boxing. Why is that?

“It’s always been a dirty business,” Carl explains. “Typically, boxers come from working-class areas, and they don’t really know about business and they just fight. They do what they’re told. I was very trusting and naïve. It’s a bit of a lawless society boxing, with no overriding, governing body. I think that’s one of the main issues. It’s a sport where you can call yourself a world champion, but so can three other guys in the same weight division. It’s a strange sport.”

Advertisement

The Frampton/McGuigan rift appears to have absolutely no chance of ever being healed. When I ask Carl about some of his fondest memories in boxing, he tells me, “I’ve got a photograph with my late grandfather, in the ring, the night I beat Kiko Martinez to win the European super bantamweight title… I’ve had to alter it a bit, because Shane and Barry McGuigan were also in the photograph, so I had to take them out of it. But yeah, I like that photograph, all the chaos going on and just me old granddad wiping a bit of sweat or blood off my face.”

Carl turned pro with McGuigan and they went to the top of the world together. Frampton beat Kiko Martinez in Belfast to win the IBF super-bantamweight title. The fight took place in a specifically constructed arena in the Titanic Quarter, from which Carl could see the roof-tops of Tiger's Bay.

Two years later, he defeated Scott Quigg to win the WBA super-bantamweight title and unify the division. Later that same year, the Irish turned Brooklyn green to watch Frampton beat Leo Santa Cruz for the WBA featherweight title. The Ring magazine awarded him Fighter of the Year, the Ballon d’Or of boxing, which he was only the fifth European to receive.

“Only the fifth European?” Carl asks. “I didn’t know that, that’s incredible. Tommy McCarthy said that to me: the Ballon d’Or of boxing, that was amazing. I had a good year obviously. I’d unified a division and moved up and beat Leo. I remember almost being embarrassed, because I’m sitting in the room with fighters that I know are better than me – Lomachenko, Terence Crawford. Previous winners include Ali, Ray Leonard, Tyson, Sugar Ray Robinson, Hagler, Mayweather and then Carl Frampton fired in the middle!”

Carl Frampton. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

LAST EVER FIGHT

Advertisement

Frampton later signed with MTK Global, the controversial, now defunct boxing promotions company linked with Daniel Kinahan, a decision which has been questioned in many quarters. But Carl has dismissed such criticisms and writes in his book, “MTK don’t pay their fighters. It’s the other way around. Their fighters pay them. Promoters get the cash from TV, sponsors and gate receipts and then pay boxers. Boxers then dole out the cuts to managers and trainers, etc. All MTK ever did for me and other fighters I know of is drive the hardest bargains they could to maximise the amount a promoter was willing to pay for a fight.”

Carl was just one fight from becoming a three-weight world champion, but was stopped by Jamal Herring in their WBO junior-lightweight title fight in Caesars Place, in Covid-era Dubai. It was his last ever fight.

“I’m glad I had a go,” Carl asserts. “Going into it, I was confident, because I sparred really well in camp. I was sparring a guy called Alex Dilmaghani, a tall southpaw. He had similar dimensions to Jamal Herring, I don’t think I lost a round against him. And I sparred another good fighter Anto Cacace, who can box southpaw as well, and don’t think I lost a round. But fighting and sparring are two different things completely.

“I remember sitting down on the stool after the first round and thinking this is going to be a hard night. My timing wasn’t what it used to be. My distance control and my explosiveness with my feet, getting in and out of range, wasn’t as good as it was. Everything just felt a little bit out of sync, that was a horrible feeling.

“But going into that fight, win, lose or draw, I was retiring. I had conversations with my wife and my kids and the team closest to me. I really broke down at the end, I can be emotional at the best of times, but watching it back, it was a bit embarrassing, a bit over the top. But I was away from my family, there was no one around, my career just finished in front of a few hundred people. And that was a bit strange.”

Does he miss it?

“I miss the camaraderie in the gym, training alongside the boys and you make some lifelong friends, I miss that,” says Frampton. “I don’t know if I miss anything else about it. People talk about the feeling of walking into the ring, but that’s not a nice feeling, you’re fucking shitting yourself at that stage. There are not many people that, in front of how many thousand people, would walk into the conflict. It’s a strange mentality to have, isn’t it? People talk about this amazing buzz, but you’re afraid, you do it because you have to.”

Advertisement

We talk about his plans for the future. Carl does punditry for TNT Sports, and has launched a whiskey, Stablemate, but he glows when talking about a recent documentary he made about young men’s mental health in Northern Ireland. I ask whether he might do more of that kind of work.

“Yeah,” he smiles, “this may be an exclusive for you, because I haven’t told anyone else about it. It’s at the early discussion stage, but the idea is, Philly McMahon coming up to teach and train me and a group of young Orangemen in Gaelic football for 12 weeks, to play a match against a Crossmaglen team. It would be good, but we’ll see what happens.”

• Carl Frampton: My Autobiography is out now.