- Lifestyle & Sports

- 19 Dec 22

Boxer Emmet Brennan drew a huge national response with his raw and emotional interview after the Tokyo Olympics. Following a difficult comedown from the event, when he struggled with drinking, he’s now plotting a hugely ambitious pro career Stateside. Can he join the ranks of Irish sporting immortals? Photography by Miguel Ruiz.

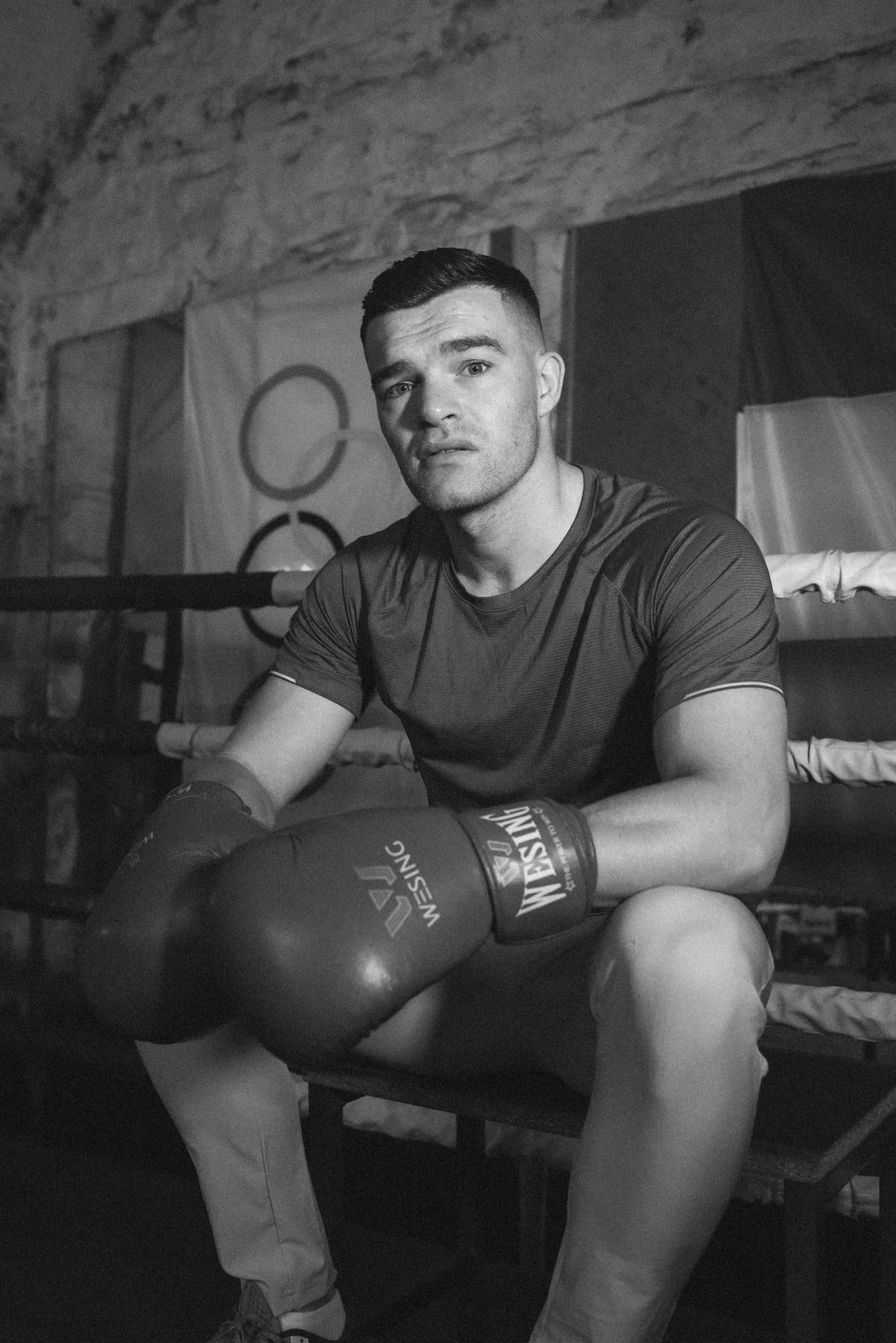

The Dublin Docklands Boxing Club in North Strand is empty, save for Tokyo 2020 Olympic athlete Emmet Brennan and our photographer. The 31-year-old local seems comfortable around the camera, but if he’s going pro, he’ll have to become adept at using the lens to his advantage.

In part, Brennan rose to national prominence for an on-camera interview with RTÉ just after his loss to Dilshod Ruzmetov in the men’s 81kg light-heavyweight division last July. His Cinderella Man story captured the hearts of a nation as he embarked on his Olympics journey, and he put up a hell of a fight against one of the best boxers in the world.

“It’s heartbreaking,” an emotional Emmet said directly after the fight, paying tearful tribute to his family. Support poured in after the interview circulated online, Brennan’s grief mingling with pride.

Since last summer, the genial Dubliner has experienced another rollercoaster year. Picking up a shoulder injury directly after the event, Emmet slipped into old vices as he headed to New York to secure a professional boxing contract.

Advertisement

Emmet Brennan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz, 2022.

Emmet Brennan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz, 2022.“Post-Olympics I fell back into drinking. I had that goal in my mind for five years, and it was the driving factor behind all my actions for that length of time. The second I stepped out of that ring and got beaten, I almost went back to who I was before I got into boxing,” Emmet tells me after his photoshoot, as we sit on the side of the ring.

He’s dressed in blue boxing gear, though today is a rest day. His shoulder is about “70 percent healed” after the injury resulted in surgery this past January.

“I drank in the Olympic village every day for the next two weeks,” he adds, candidly. “No one ever prepares for what’s after the Olympics, when you go home. I was lost. I went to New York in March, and my shoulder wasn’t recovering. My mother and my sister came to visit, and I turned up drunk.

“I realised that alcohol was a problem for me again, and promised myself I was going to give it up, and now I’m six months sober, which has been the best thing I’ve done in my life. I’ve just been so productive. The shoulder is healing, I’m about to start a professional career, opening two businesses and training, passing on my boxing skills to the kids in this club. Definitely, quitting alcohol has just shone a new light on my life. I’m proud of it.”

Ironically, bringing his mother and sister to New York was the ruse he presented to the Credit Union when requesting a loan for Tokyo 2020.

“They’ve been to New York now!” Brennan laughs. “I bought tickets for my ma’s 60th and my sister’s 21st, but it got called off over Covid. They came over this year, though. I had no choice but to get a loan for Tokyo, because I was working part-time instead of being a full-time athlete.

Advertisement

“I knew if I told the bank that I’ve €400 in my account and asked for a loan to go to the Olympics, they’d have said no. I told them it was for car insurance and the US holiday. The money came the next day.”

His Big Apple trip in the Spring was tainted slightly by his troubles with alcohol, he concedes, but it turned out to be a major wake-up call that led him down a new path.

“I knew I’d fucked up because I was out the night before until about 8am,” he reflects. “I was meeting my mother and sister at 2pm and I basically turned up from the night before. I could see the look of disappointment in their eyes, but they didn’t actually say anything to me.

“My ma’s a peculiar character, and I knew deep down that she was disgusted. Me being me, I had 10 days left in New York by myself and I knew I had to stop drinking when I got back to Dublin. I got it out of my system. That’s the way that I think, I’m all or nothing. I drank for 10 days straight, and I haven’t drank since. I don’t even have the urge.”

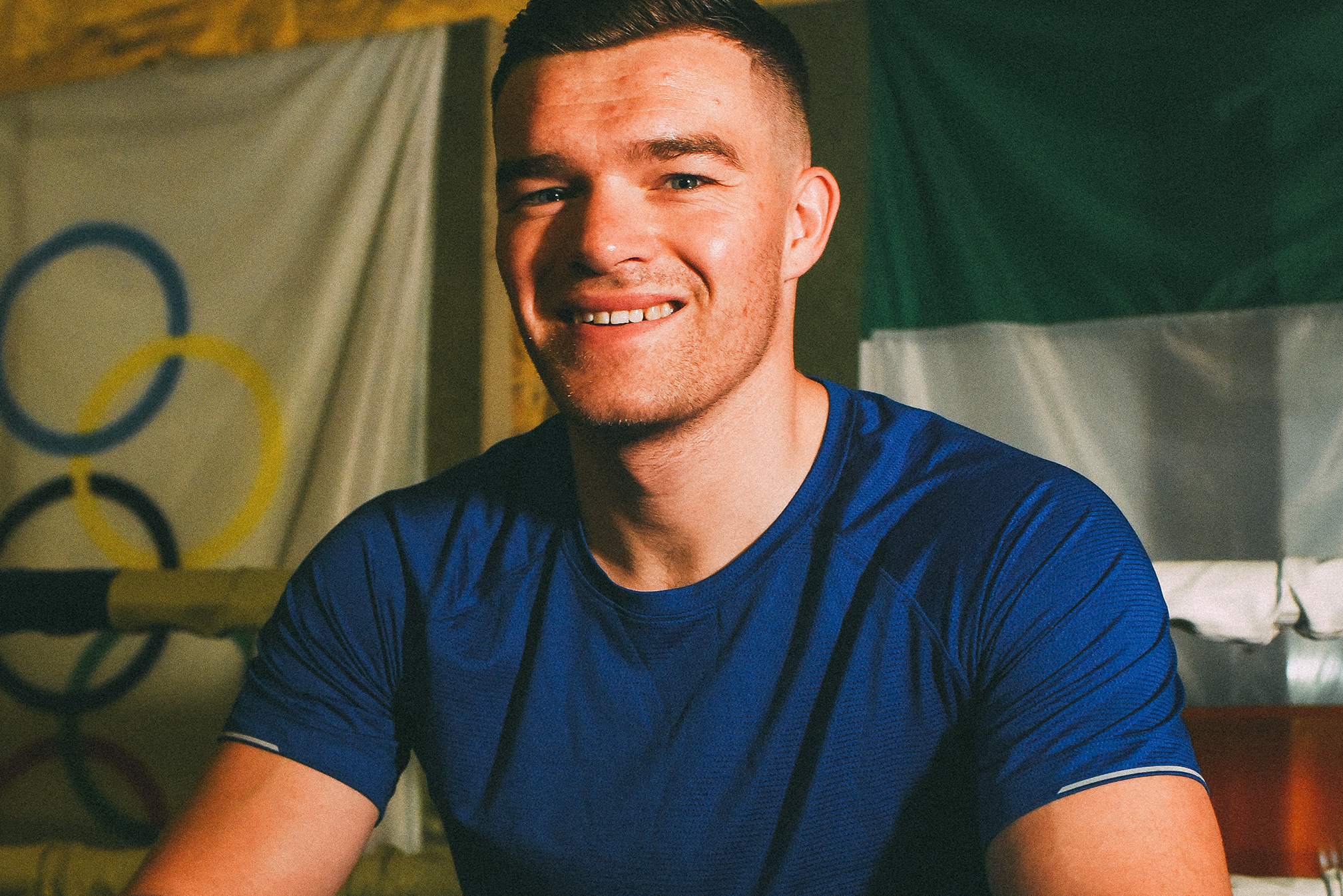

Emmett Brennan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Emmett Brennan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.He’s in a more positive frame of mind these days.

Advertisement

“I’m onto bigger and better things,” he says. “I’m definitely not an addict, but I’ve known that I’ve had drinking problems for a long time. I’m not young, but Eric Donovan is 37, and just became a European champion two weeks ago, and Dennis Hogan in Australia is 38 and became a world champion last weekend. Neither of them drink.

“They live a good life, and have won major titles at that age. I’ve still got seven or eight years until I get where they are. If I put my head down, I could be Irish, Celtic, European and World champion. That’s the mindset I’m in.”

Brennan didn’t have the usual entry into the world of boxing, returning to the sport at the relatively late age of 25, after finding himself dissatisfied with life.

“I was an apprentice pipefitter,” he recalls. “I started at 22 on €5 an hour. It was a very low-paying job. I did that until I was about 26, and then I got a job with Dublin City Council. I worked in a gym called The Markievicz. I could work my own hours around boxing, which is great, and go to Germany for training camps. That helped me financially.

“At the same time, you’re still working on top of being a full-time athlete. It was quite hard, but you have to do what you have to do. Up until 24 or 25, I just drank, worked, gambled and trained a little bit. You’re not bringing in a lot of money if you’re doing those things. I had no savings.

“By the time I got to 28, all my money was gone on training. Full-time athletes finished training on Fridays and rested for the weekend, but I was going straight to work before the Olympics. I was studying for a degree at the time in strength and conditioning online in Setanta College in Thurles. All I did was work, train and study for 12 hours a day.”

Emmet was a shy kid who found solace and clarity in boxing in St. Saviours Olympic Boxing Academy in Dublin, which has produced some of Ireland’s best fighters.

Advertisement

“I was always driven but very, very easily led,” he laughs. “When I was in my early twenties or late teens, I would have been emotionally weak, not nearly as strong-minded as I am now. There’s a lot of people that age who are lost and need direction in life. I lived a life of partying, but I’d take the hard graft of boxing - where you have goals in front of you - over hangovers, lying to your family and having no money.”

“My mother’s quite straight in her assessment of what I’d be doing, but at the same time, never really judged me. I probably gave her a lot of sleepless nights when I was out until 9am. There were times where she could have kicked me out of the house if she really wanted, but she always gave me a second chance. If I’m wrong, she’ll tell me, so I was surprised that she didn’t say it to me in New York. I knew she wasn’t happy. She’s a mother and she wants the best for me.”

Emmet Brennan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz for Hot Press.

Emmet Brennan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz for Hot Press.Brennan certainly appreciates her support.

“She’s been amazing in my boxing career, because I was 28, 29, 30 living at home rent free, getting meals cooked for me,” he notes. “Stuff that I shouldn’t be doing at that age, but she realised my dream was to go to the Olympics and become a successful boxer. I just didn’t have the time or money to give up. She came in and took the role, but in return, she wants me to be a good person. It’s not much to ask.”

Brennan describes his family as “tight knit”.

“When I went after the Olympics, my whole family sacrificed a lot for me,” he reflects. “Most athletes are selfish, and you have to be. That’s not really fair to ask of my family. It’s my dream, not theirs. They all helped out in their own way. My sisters were 25 and 22 at the time of the Olympics. I’m very grateful for what they and my brother have done for me.

Advertisement

“It shows a lot of love. My family was at home when I qualified, but I was in Paris. My mother never looks at the fights, so she and my sister went on a walk to the park. My dad rang them and told them to run home after the result for a video call – they were all jumping around the room! It’s a team effort, and they sacrificed as much as I did, so they were over the moon.

“They were probably a bit relieved as well because I went all in. I gave up finances, my personal life, a work life, my body… everything to get there. They knew if I didn’t get to Tokyo, I would have been very down for a couple of months. They were happy I got over the line.”

When he arrived back in Dublin it was on a rooftop bus with friend and gold medal winner Kellie Harrington. He speaks extremely highly of the Portland Row native.

JAMES CROMBIE/INPHO.

JAMES CROMBIE/INPHO.“I think Kellie will win the next Olympics. I’m very, very confident about that,” he asserts. “She looks happy with what she’s doing, so I’m not sure about whether she’ll turn professional. If she wins the Olympics next time around, she’ll be Ireland’s only two-time medal winning athlete. That’s enough motivation in itself to stay amateur. Whatever she does, she’ll do it to the fullest because she’s a great athlete.

“I still have people coming up to me on the street in my community just to say well done, and they always ask what’s next. There’s people looking to get behind me all the time. The locals were genuinely happy for me, which I didn’t realise. You’re away in a bubble, so you don’t really see the effects of what’s happening at home.

Advertisement

“It was quite a humbling experience, because I never expected it. There are a few kids in this club and their mothers had texted me to ask about the club’s opening times, do they take girls and boys of a certain age. That has a lasting effect on the community when you have more boxers walking through the door.”

Despite the warmth that flooded in, Emmet still felt a massive comedown after Tokyo 2020. The lack of available support for Olympians is something he speaks openly about, be it due to bitter disappointment or the sudden drain of adrenaline.

“I just wanted to forget about the result, drink, enjoy the Olympic village and be around other athletes, but I think there should be check-ins a few months and weeks after the event,” Emmet nods. “Not just ‘How are you feeling?’ If someone asks an Irish person, they always say they’re grand. You should have to go into the high performance unit, or even just give people the option. Looking back, I know that I wasn’t okay.

“I was looking for every distraction under the sun to forget about it. Normally you get a bit of exposure after the event, sponsors want to come on board. I didn’t get those chances. A lot of it was through my own fault of drinking, a shoulder injury and not having the right mind-frame. I was hit hard, because I couldn’t capitalise on the sacrifices myself and my family made to get there.”

After securing his Olympics spot against all odds (combatting injuries and a lack of sparring), Brennan is now ready to hang up the amateur singlet and set sail on a Stateside adventure in the professional ranks. Having spent time in the US working with John Duddy and Feargal McCrory earlier in the year, he believes that his future lies in the paid ranks of the sport.

Emmett Brennan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Emmett Brennan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Advertisement

Brennan’s plan is to base himself on the east coast for six weeks on, six weeks off, working his way up through the super middleweight division, while drawing on the massive Irish support in the five boroughs of NYC.

“As a pro, my plan is to go through Ireland first,” he tells me. “Normally with boxing, you start off by building up a bit of a record and get wins under your belt. Because I’m 31, I can bypass a lot of people. I’m going to try and get an Irish title within three or four fights, a Celtic title in six fights and within two years, I want to be European champion. I’d only be 33, so then I’ve got a few years left to get a world title and go up in the rankings. I don’t really care who’s in front of me, in terms of names.”

He elaborates further on his intended route.

“The plan with New York was to suss things out and see if I liked it,” he continues. “I also wanted to see if I could get a contract from a promoter over there, plus a following. There’s no point in moving across the pond if no one’s going to turn up to your fights. I loved it, the people were great. There’s a huge drinking culture in New York, so I’m not going to stay there full time.

“I got offered a contract over there, but it wasn’t good enough. I turned it down, which I’m very happy about. I didn’t want to be signed to a two, three, four year contract when it wasn’t worth enough money. I assumed that no one would know me, but I got noticed a few times by Irish people over there.

“I asked them if they’d come to my fights and it looks like I’d sell a few hundred tickets straight off the bat, and that gives me motivation to do big shows. It’s about making as much money as possible over the next few years.”

The business of pro-boxing isn’t worlds away from the music industry, where there are certain big names you don’t want to get on the wrong side of.

Advertisement

“With big promoters, you have to have some kind of backing behind you, or presence,” says Brennan. “At the same time, you have to say the right things. You’re not necessarily always going to be honest. For instance, a boxer failed a drug test at the weekend and a lot of people stayed silent on it, because he’s under the biggest promoter in the world.

“They didn’t want to piss him off, because they wanted to work for him. A lot of people were totally quiet, and that’s down to managers, commentators, ring announcers. If they talk badly about that promoter, it jeopardises their chances of working for him. I wanted to be open about everything, and going back to boxing helped me do that.”

Brennan reveals he had a desire to debut on the undercard of Katie Taylor and Amanda Serrano’s April 2022 Madison Square Garden fight. Fellow Dublin local (and Hollywood star) Barry Keoghan even tweeted his support.

Make @emmetbrennan91 happen @EddieHearn @MatchroomBoxing

Emmet I will walk you to the ring too brother 🥊🏅🇮🇪☘️— Barry Keoghan (@BarryKeoghan) February 13, 2022

“Coming from the likes of Barry Keoghan, if sponsors can see that, it’s huge,” he smiles. “They want clicks online and exposure. Realistically, sponsors are more than likely on your side because they like you, unless you have thousands of followers. They like your journey and where you’ve come from. Fortunately for me, my story was hard, but it’s something that a lot of people can recognise in themselves.

“In terms of Katie, she doesn’t have to go down the showmanship route or trash talk because she does it all in the ring. A lot of talk is cheap. I’ve had a year to look at the likes of social media and marketing, seeing what would work for me. Calling people out might be something for a 21-year-old but not someone my age.

Advertisement

“It’s entertainment for some people but I see it as a bit arrogant. Big names like Katie and Anthony Joshua don’t do that. It’s not about their personality as a tool.”

In terms of social media and clickbait, what did Emmet think of the Sky Sports interview with the Ireland women’s football captain Chloe Mustaki?

Photo by Mick O'Shea/Sportsfile

Photo by Mick O'Shea/Sportsfile“That’s the media in a nutshell, but the public probably plays a big part in it,” he says. “Personally I think it was taken completely out of context. They’ve just had a remarkable achievement, they’re the first Irish women’s team to make it to a World Cup. That should be celebrated, it shouldn’t be overshadowed by a video online, but unfortunately it has been. In terms of women’s sport in general here, this is the start of a golden generation.

“Women are killing it right now. It’s only going to get better. With boxing, women are ahead of their time. They’re getting funded the same as men, which is only right, and you’re seeing the results from that now. They encourage each other. If other sports follow through, you’ll see it across the board.”

Brennan has more observations to offer on the subject.

Advertisement

“The male boxers here aren’t as tight-knit of a community as the ladies!” he smiles. “With the Irish Olympic boxing team, I’ve been following them with a bit of envy because I’ve been on the sidelines. I’m obviously delighted for my team mates who are doing well for themselves, but I’m also jealous, and social media is bad for that.

“I’m happy for them, but being genuinely honest, you’re going green in the face because you’ve worked hard to get into a similar position. Aidan Walsh could go on and win Paris, which would be amazing. He got bronze last time. Kurt Walker has gone professional, and you’re looking at the likes of him and saying, ‘Jesus, that’s where I want to be’. It gives you encouragement.

“If I work as hard as I can and do all the right things, ticking the right boxes, six months down the line, I could be fighting as a professional, being on big shows, having good sponsors, being on television and seeing money coming in. I want to fight in front of the world.”

Read more Frontlines interviews in the new issue of Hot Press, out now.