- Lifestyle & Sports

- 21 Jul 20

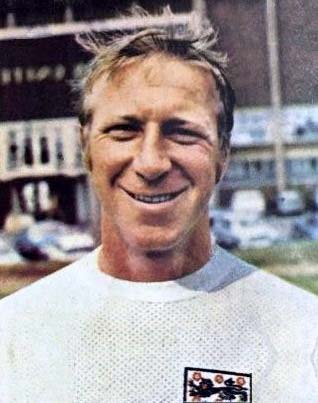

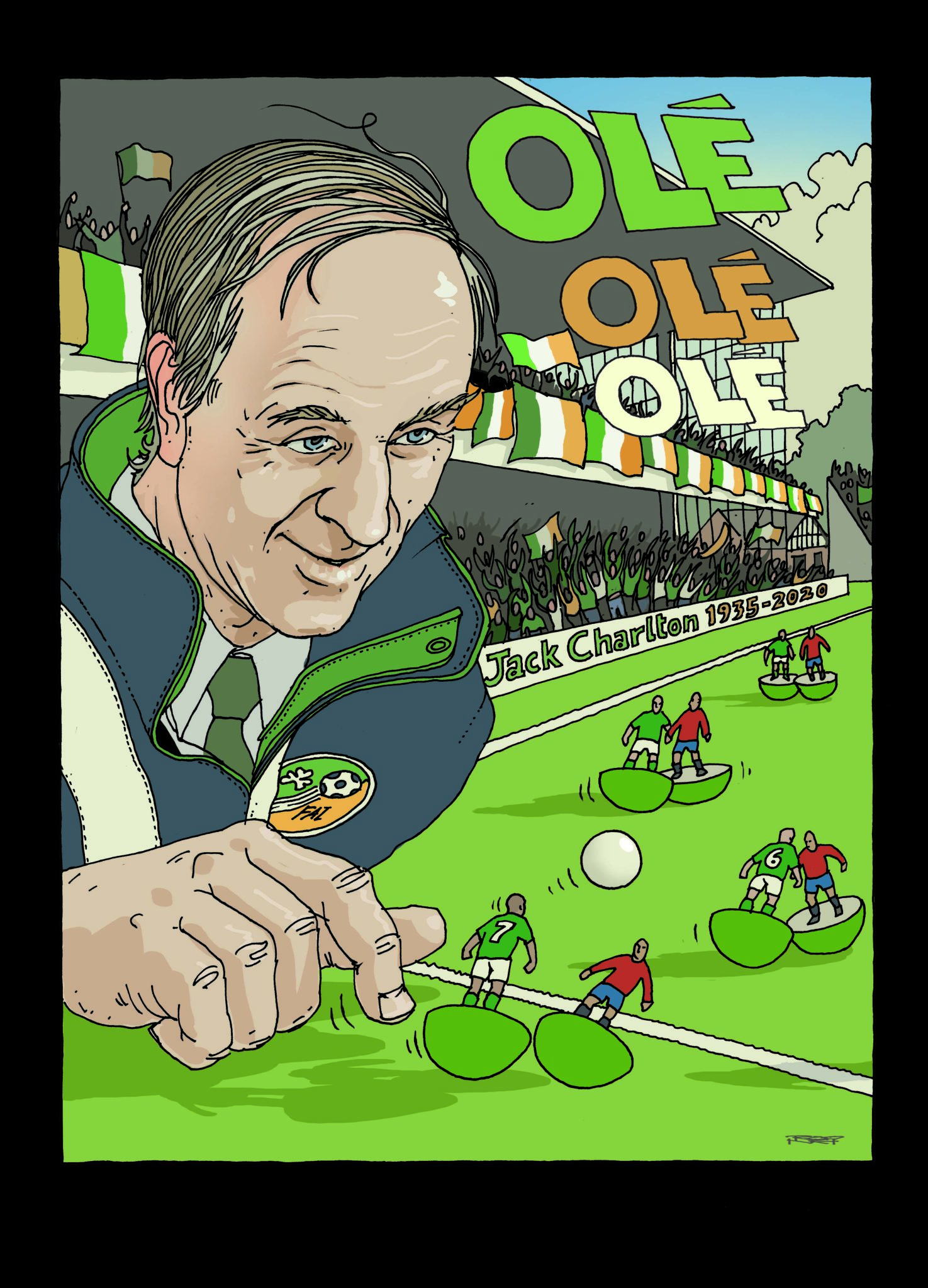

Jack Charlton (1935-2020): An Irish Legend

He was a World Cup winner with England in 1966. And yet it was during his extraordinary tenure as Ireland manager from 1986 to 1996 that the man they called Big Jack made his greatest impact – bringing joy unconfined to an entire nation, and contributing in a remarkable way to the modernisation of what had in so many ways been an introverted little place on the periphery of Europe.

Big Jack is dead. I know that sounds brutally direct but it feels right. Big fucking Jack is dead.

There is no room for misunderstanding in that simple sentence. And therein lies a deeper kind of truth. Because there might, of course, be any amount of room for misunderstanding if he – this particular rough-hewn English man – hadn’t had such a profound and lasting impact on the world as we in Ireland know it.

In Ecuador, Iceland, Saudi Arabia or Fiji, looking at this article, they might be thinking ‘Who is this Big Jack then?’ In Germany, France, Holland and Italy, the reaction might well be the same. Jack Charlton won a World Cup medal with England in 1966. They’d know that. But what did this man Big Jack ever achieve? What indeed!

As manager of the Irish team, did Big Jack win a major tournament? No. Did he adorn the beautiful game with football that will go down in the annals? Hardly! So go on, spit it out! What, really, did he achieve? Tell us.

Come gather around children, wherever you roam – and listen... do you want to know a secret? Do you promise not to tell? Closer: let me whisper in your ear...

It is a true story, of course it is: there are those who credit this surname-less wonder with transforming an entire country. With turning it inside out and upside down and getting the very best out of, more or less, an entire nation. I kid you not.

These modern folklorists may even be three-quarters right.

Certainly, Big Jack brought joy and celebration and – fuckit – oceans of sheer madness, on a scale that had never even been dreamt of before, to this historically troubled little island nation. He inspired us to laugh and dance and hug and sing. He made us appreciate how good it was to be alive, as long as you could fully immerse yourself in the sheer exuberant crazy pleasures of the nowness of the moment.

He took us, citizens of Ireland, out of a kind of collective torpor, an immiserating lethargy, that had hung over the place for the previous Jesus knows how many years. And he brought us, Pied Piper-like, into a footballing wonderland that was hard to describe back then, and is even harder to evoke now.

I wouldn’t want anyone to get the wrong impression. Jack never promised anyone a rose garden, and that’s not what we got either. He had his critics, the footballer-turned-pundit Eamon Dunphy most prominent among them. On occasion, I ended up on that side of the tactical fence, for what I still consider good reason. Let’s just say that the prevailing view among people who knew a bit about football was that Jack’s style was more agricultural than horticultural. Some argued that, with a different man in charge, we’d have gone even further in terms of success, and given Irish people a lot more to be proud of in the process.

But looking back now, what might have been pales into insignificance alongside what was actually achieved by Big Jack and the Irish team – or rather the Irish teams – he managed.

It is an incredible, and often very moving story.

UNLIKELY HERO

I’ve said it before here. I am a great believer in chaos theory. Small things can and do shape our destiny. That doesn’t mean that we should ever think of ourselves as being among the chosen ones, part of some kind of spurious elect, with an imagined divine presence out there intervening in human affairs on our behalf.

The opposite is the case. The great songwriter Guy Clark sang: “Let the chips fall where they will/ I’ve got boats to build.” But, of course, in that singularity of purpose, he was the exception. For a huge proportion of the people who end up in public life, or battling it out on one stage or another, a roll of the dice can play an immeasurable role. You get lucky and ride the wave as best you can. And thus it was with Jack.

He took over in 1986, leading Ireland into the Euro ’88 campaign. A mere eight countries made it to the finals back then. It was a horribly punishing competition and Ireland had a tough draw in Group 7, alongside Belgium (who had just come fourth in the 1986 Word Cup), Bulgaria and Scotland. In the 1980s, Scotland were a far more serious proposition than they have been for many years since. The same was true of Bulgaria.

We hadn’t done badly in the group games, most notably beating Scotland away in Hamden Park, courtesy of a rare Mark Lawrenson goal, and drawing twice with Belgium. But we still looked out for the count, with Bulgaria needing only a draw from their final home game against Scotland to win the group. The potential rewards for our Celtic cousins were non-existent. It had all the appearances of a shoo-in.

It may well have been that Bulgaria thought so too. It didn’t happen that way. A goal by the classic minor journeyman footballer, Gary Mackay, in the 86th minute of the game in Sofia gave Scotland a shock 1-0 win. With football logic thus turned on its head, completely against the odds, we topped the group. We were in the finals.

How many chances did Bulgaria miss? How often had Gary Mackay spurned similar opportunities in the past? And yet, that unlikely hero’s goal kick-started what would become a storied era. It was crazy stuff to begin with, and it would get far, far crazier.

There is a phrase in football: goals change games. Well, this one had changed far more than a game. Everything that Jack Charlton did, everything he represented – his better qualities along with his lesser ones – was seen in a more positive and forgiving light than would otherwise have been the case as a result of that initial almost accidental and certainly hugely fortunate success.

And in truth, in so many ways, Jack rose to the occasion. He grabbed the opportunity that had been presented to him with both of his big, fisherman’s hands. He became – deservedly so in very many respects – an Irish legend.

PUT ‘EM UNDER PRESSURE

The football arguments were only, it turned out, starting. Jack had a theory. As a defender of the old school, temperamentally he was firmly against taking risks. He didn’t want any of what he called ‘fannying about’ at the back: better that the ball be launched into Row 94 than allowed to bobble on the edge of your own penalty area. Keeping the ball wasn’t his thing. Upsetting the opposition was. Making them as uncomfortable as possible.

To carry out the game-plan, he wanted players in his team who would follow instructions.

His innovation, if that’s the right word, was to bypass midfield. Instead of picking up the ball from the goalkeeper or defence he wanted his middle four to fight for the scraps at the other end. And so Packie Bonner was told to go long with his kick-outs at every opportunity. To put it as high as possible, making it harder for the defenders to judge the flight of the ball. The full-backs were instructed to send it down the line. The strikers knew where it was going to go and could get a yard or two on the opposing centre-backs, more or less every time. Or that was the theory.

As a centre-half, Jack had hated having to turn: and so he instilled in Irish players the importance of forcing opposition defenders to turn by putting the ball in behind them.

Along the way, when the inevitable Irish long ball was hit down the middle, he instructed the Irish strikers to jump not to win it – he didn’t want it headed on to the opposition keeper – but to force a scuffed header from the defender that would be fodder for the Irish midfielders running onto it.

It was all simple stuff that eschewed creativity or inspiration. And in an era when Ireland had some of the best footballers in the English game, and Liam Brady was flourishing in Italy, to anyone who loved seeing the ball played on the ground, his style was anathema. Perhaps, with a different manager in place, bringing a different kind of best out of a squad that included some genuinely superb footballers, we’d have done as well or better. That is one of the great imponderables.

But it would be wrong to say that Jack Charlton was some kind of throwback to a neanderthal era. In one respect, he was ahead of his time. In addition to putting the ball behind defences and forcing them to turn, or going down what became known as Route One to get it into the opposition penalty box quickly, Jack was an early adapter to the idea of pressing from the front.

He wanted his forwards to act as the first line of defence. John Aldridge, one of the great goal poachers of the era in England, and a star in a very good Liverpool side, famously complained that he had to run his legs to stumps for Jack. He went 19 games without scoring for Ireland, and Jack didn’t mind. John did what he was told. He put ‘em under pressure – and the opposition hated it.

It is done now with greater sophistication by Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool, and by teams managed by Pep Guardiola, among others. It is an accepted part of the modern game. But Jack was the highest-profile early advocate of the principle: put the opposing defenders under pressure; win the ball high up the pitch – and you can do all sorts of damage.

And Jack’s Ireland did.

A GOOD HEART

The opening act of the Euro ’88 finals couldn’t have been any sweeter. We beat England 1-0 in Gelsenkirchen, courtesy of a Ray Houghton header. It was the beginning of a decade of glorious madness. We drew with Russia and were beaten by a brilliant Dutch side, only as a result of a goal that was the result of an unlucky defection. We didn’t make the semi-finals, but the Ireland football team had captured the hearts and the emotions of the Irish public.

Christy Moore wrote the marvellous epic ‘Joxer Goes To Stuttgart’ about the adventures of the Irish in Germany in 1988. And from that initial high, and the wild scenes that greeted the players on their return home, we rolled on through Italia ’90 and USA ’94. It was a golden era. But it was also a magical, extended moment in a wider sense.

It was as if that infamous, ancient inferiority complex, which had dogged Irish people over the decades, and maybe longer, was shed finally in the white heat of competing at the top level in international football. It coincided with U2’s ascent to the role of Biggest Rock Band on the Planet. Sinéad O’Connor and Enya proved that Irish women were as capable of hitting the heights as any of their male counterparts. And in December 1990, Mary Robinson was inaugurated as the President of Ireland, becoming the first woman to hold the office.

In many ways, these seismic events were the culmination of a process that had begun towards the end of the 1970s. There were other reckonings to be engineered too, most notably in relation to the twisted dominance exerted by the Roman Catholic Church over social and political life on the island. But the cumulative effect of the roller-coaster that started in 1988 was to engender a real feeling that Ireland had arrived in the modern era; that the days of isolationism and subservience were over.

It helped that, for all his stubborn-ness, Big Jack was a likeable character. He was honest and straightforward. He had a sense of humour. He was far more intelligent than his initial bluntness might have suggested. He was warm. And he had a good heart.

He came to love Ireland. And Irish people – or most of them, at any rate – loved him. The teams he managed – and there were three at least during his decade at the helm – developed a sense of camaraderie and collective spirit that was unique. And that fed on into the relationship he, and the players, enjoyed with the Irish public.

There were controversies, with Big Jack’s style being denounced entertainingly by Eamon Dunphy and forensically criticised by John Giles. But even that became part of the national pantomime. The RTÉ team were brilliant. They had a sense of humour. And they added to the feeling that Irish people could do it – whatever ‘it’ might be – as well or better than anyone else. Our pundits were, it turned out, also world class.

GUIDING PRINCIPLE

None of that matters much today, you might say. But that is not necessarily true. For a start, we are all benefitting now from the changes – hard fought-for over the preceding decades – that finally enabled the referenda on same sex marriage and abortion to be passed. The Irish football success story was, of course, just one of the catalysts along the way, that helped to open this country up to a stew of largely positive outside influences. It lifted the national mood. It helped to get Mary Robinson elected. It generated a new feeling of pride. It was a vital part of our finally growing up.

There was another side to it that is also worth remembering today. In so many respects, football is a microcosm of life. The ethos of Big Jack’s team was one of collective commitment. The prevailing attitude was positive. It was mutually supportive. It was based on the principle that we were – that we are – in this together. That divisiveness hurts us all. That negativity breeds deeper negativity. That fear is the enemy. That in solidarity we can achieve far more.

In a mixed-up, shook-up, and in so many ways, screwed-up world, that much remains true. For people in Ireland, it should be a guiding principle. Cruelty and the desire to punish: these are things that we had begun to leave behind. That’s where they belong. In the past.

Together we really are stronger. That was Big Jack’s guiding principle. It was Mary Robinson’s too. It is what won the referenda.

We should never forget it.

RELATED

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 06 Nov 25

Winter Distilling Special: Raise a glass and say “Sláinte!” to all of the brilliant distilleries out there

RELATED

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 22 Oct 25

Hot Flavours: Highlights from Dublin Beer Festival – plus Jess Murphy releases The Kai Cookbook

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 20 Oct 25

Discover European Mushrooms: Learn to make Chestnut Mushroom Soup with chef Eric Matthews of Kicky's

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 11 Oct 25

Special Report: Bohemian FC Women's Squad - Making Giant Strides

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 07 Oct 25

Report: Why We Must Not Fail On Climate Targets panel at Electric Picnic with Re-Turn and more

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 22 Sep 25