- Opinion

- 21 Dec 21

As part of our 12 Interviews of Xmas series, we're looking back at some of our unmissable interviews of 2021. Following the release of her acclaimed debut album, Skin, in November, Joy Crookes stopped off in her dad’s hometown of Dublin for a sold-out headline show at The Academy. Ahead of the gig, she sat down for a candid conversation about Irishness, gentrification, Blindboy, the Palace Bar, protest music, and more.

We all contain multitudes – that’s as true for you and me as it is for Joy Crookes. The vastness of the human experience, and the complexity of identity, are realities that have not only shaped her fearless debut album, Skin, released in October, but have largely informed her entire life – growing up in a multicultural area of South London, with a Bangladeshi mother and an Irish father.

As a singer and songwriter, the 23-year-old has embraced classic soul and jazz touches that hark back to decades past, while simultaneously rooting herself firmly in the world of modern pop. But with an ever-growing collection of accolades to her name, including a Rising Star nomination at the 2020 BRIT Awards, as well as streams in their hundreds of millions, she’s had to withstand increased efforts to apply oversimplified tags to her artistry – including, most notably, ‘the next Amy Winehouse’.

“That’s definitely part of the package,” she tells me, sipping on a bubble tea as we sit inside the currently empty Academy in Dublin. In just a few hours, she’ll be standing up on that stage in front of a sold-out crowd, serving up soulful ruminations on the political, the personal, and the overlap between the two.

But right now, still dressed against the Abbey Street cold in an oversized green jacket, she speaks with a grounded, sometimes world-weary calm that belies her relatively young years – offering up gems of hard-won wisdom in place of the typical unbounded idealism and optimism of other artists her age.

Advertisement

“When you’re a woman, regardless of what industry you’re in, you’re more likely to be compared,” she resumes. “Because, for some reason, the comparison is like a digestion tablet. It’s like Yakult, but for lazy human beings that can’t be arsed to go and check out what you do. So it’s much easier for journalists to put you into a box. For me, there are so many different boxes. There’s the Amy Winehouse box. There’s the ‘Oh my gosh, she’s Bangladeshi-Irish-British’ box. Or the South London box.

“What all of that screams to me is lazy journalism, to be honest,” she laughs. “People can sit with me, and have a conversation, and understand – after releasing an album called Skin – that we as human beings are not necessarily defined by where we come from. We’re defined by so many things. We’re so multifaceted. Our skin, so to speak, is made up of so many layers.”

It’s a truth Joy Crookes has been living since she was a teenager – balancing regular adolescent shenanigans with a double life as a songwriter. ‘Poison’, which features on Skin, was penned when she was only 15.

“I was just really angry,” she says of the track’s genesis. “It took me 10 minutes to write the song, and none of the lyrics have changed, apart from one word. I changed the word ‘because’ to ‘but’, and that was it.

“It’s weird, looking back on it,” she adds. “But at that time, it felt like the most natural thing to do. A lot of people have felt a natural inclination towards making music – especially in Ireland! – but they keep it as a hobby. I wasn’t trying to become a musician either.”

From those early years, she was also immersing herself in wider influences, including the protest songs of Nina Simone and The Clash. It’s a genre-spanning legacy she’s now found her own place within – as she tackles a whole new set of social ills through her music.

Advertisement

“If you look at both Irish culture and Bangladeshi culture, protest art is so important – and not even that long ago," she notes. "The songs that any child who grows up with an Irish parent might inevitably learn aren’t just telling a fictitious tale. It’s the actual history and lives of Irish people, over the last 800 years.

“I had an Irish dad, so I had to listen to all sorts,” she continues, with a reflective smile. “‘Raglan Road’. And different poets, like Seamus Heaney. And The Pogues. But also classic old songs.”

Those Irish roots remain strong. Last year she covered Van Morrison’s ‘Madame George’ as part of a special Hot Press series, while one of the earliest videos on her YouTube channel is a stripped back cover of The Pogues’ ‘A Pair of Brown Eyes’, recorded when she was just 14.

And despite having spent recent years rubbing shoulders with more than her fair share of international stars, she’s much more interested in praising the likes of Blindboy Boatclub and Gemma Dunleavy, both of whom she’s been messaging on her phone ahead of showtime.

“I fucking love Blindboy,” she enthuses. “I’ve messaged him for years, and he’s been really supportive. He’s not in Dublin at the moment, is he? I might actually ask him if he wants to come to the show, but I reckon he’s in Limerick...”

Another Irish artist she’s more than willing to rave about is Tallaght rapper Jafaris, who she collaborated with in 2019 on ‘Early’ – a single that has since clocked up over 16 million streams on Spotify. We rapidly come to a resounding agreement that he deserves to be arena-packing massive.

“We all think that,” she sighs. “I don’t understand what’s wrong with this country, in that respect. Jafaris is like one of my best mates.”

Advertisement

The pair shot the music video for ‘Early’ – “one of the funnest” she’s ever done – between the iconic Grogan’s pub, Phoenix Park and her gran’s house in Dublin. But her personal favourite spot for a pint in town?

“I love Palace Bar, that’s one of my favourites,” she reveals. “I like Grogan’s, but I never used to spend much time there. My dad used to take me to Palace Bar, and be like [launching into a hilariously cruel impression of his Irish accent], ‘All the writers and everyone would sit here and drink… Take it in!’ We used to drink on Meath Street as well – that was where my grandad would go. That’s proper Dublin!”

Will she be having a pint while she’s here?

“More than a pint, I think,” she smiles. “Bloody hell...”

She’s also in the market for a Claddagh ring during her time in Ireland.

“I’ve lost the one that my dad gave to my mum,” she says. “But I think that was semi-symbolic – because they didn’t last very long…”

Advertisement

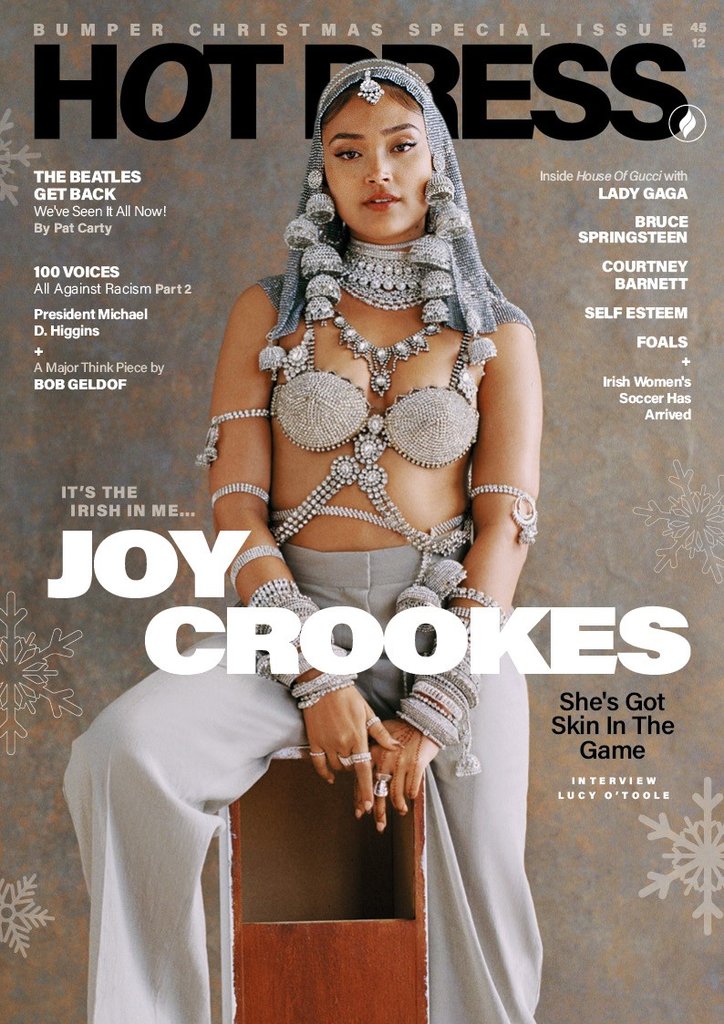

Joy Crookes at The Academy. Thursday 11th of November 2021. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Of course, off the tourist trail, Joy is well aware that there's another side to Ireland.

Whether derived from ignorance or something more overtly hateful, there’s too often been a tendency to equate ‘Irishness’ with ‘whiteness’ – particularly in conversations about Irish hip-hop. Despite the major success of Irish rappers of African descent – including Jafaris, JyellowL, and drill artists like Offica and A92 – it’s taken time for some listeners to accept their music as ‘real’ Irish hip-hop.

“I can see it,” Joy remarks. “Out of my own experience, of being someone who’s been boxed and labelled – and going from, ‘Ireland doesn’t fuck with me’, to, ‘Now Ireland fucks with me’ – I can see it. And I don’t think people realise I can see it, but I’ve noticed it for a long time. These are discussions I’d be having with Jafaris years ago.

“I am the only brown person in an Irish family,” she continues. “So it’s not even a thing that’s new to me. I’ve always noticed it, and I’ve always noticed being the odd one out. When you say ‘Irish’ you don’t think of Black Irish people or brown Irish people – when that’s just as much a part of the history as anything else.”

As an avid fan of The Blindboy Podcast, and a self-confessed history buff, Joy knows what she’s talking about.

Advertisement

“Bindboy has talked about Frederick Douglass coming to Ireland,” she reflects. “And Daniel O’Connell being like, ‘This man goes through suffering, and you, as Irish people who have been under Penal Laws for however many years, go through a similar – though not the same – suffering. You must respect everyone who looks like this man when you go over to America. When you emigrate, this is the man that you have to be kind to.’ Whenever any of that shit happens, I always think of that story of Frederick Douglass and O’Connell.”

Re-examining our definition of ‘Irishness’, she reckons, is crucial.

“The huge issue that I’ve always noticed is that white Irish people try to pardon themselves,” she begins. “Like in The Commitments, when they call themselves ‘the Blacks of Europe’. Not disregarding Ireland’s history – because I know a lot about Ireland’s history – but you can still walk down the street and present as a white man, before you open your mouth, and someone knows you’re Irish. What about when someone can’t hide the colour of their skin?

“Ireland is given this pedestal because of 800 years of colonisation,” she continues. “Understandably – Ireland has been through things! But there are people who say, ‘Irish people were slaves too!’ No, they weren’t. Yes, they were taken over as labourers, and yes, they were under British power – and wrongfully so. However, they could still work their way up to be slave masters.

“So the real issue is talking about what Irishness means. Do we lean too much into the fact that we have suffered, to then pardon our fuckeries?”

‘Feet Don’t Fail Me Now’, one of the highlights on Skin, finds Joy exploring similar questions, in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement – and how it can be easier to be a performative activist than to actually engage with these issues in a meaningful way: “Retweeting picket signs / Put my name on petitions, but I won’t change my mind / I’m keeping up appearances / The dark side of my privilege...”

Advertisement

“You have to hold yourself accountable first, before you hold anyone else accountable,” she posits. “Regardless of what race you’re from. And especially as a brown person, I need to hold myself accountable. Non-Black ethnic communities are just as guilty as everyone else. We’re all just as guilty as everyone else. If you’re the type of person to go around pointing fingers, you need to be pointing the finger at yourself first.”

Elsewhere on the album, ‘Kingdom’ finds her venting her frustrations with the Tories, while ‘Power’ is an exploration of the abuse of political force – inspired, she says, by “the inauguration of Trump.”

“I was 18, and he had just been elected,” she reflects. “I was wondering what that meant for the rest of the world, and sub-sections in society – so what it meant for women, or people that ‘lack power’, or have had power used against them.”

On ‘19th Floor’, meanwhile, she pays homage to her local area in London and the strength of her family – while also mourning how gentrification has “stripped the life out of these streets.”

“If gentrification happens in a city – which is inevitable, across every major city in the world – then you will be somehow affected, and there’s no control,” she says. “It’s the same as power, and the abuse of power. As much as you sign petitions, and whatever else, the problem with gentrification is that it happens literally in front of us. And we don’t even realise it until it’s over. It’s beyond our power.

“Gentrification starts with students,” she adds. “It’s really hard to blame students – because you wouldn’t turn around and go, ‘Students it’s your fault! You’re doing this!’ Because they’re just trying to get their education. But before you know it, your block of flats has turned into a student accommodation. And these students move in, and some of them can earn much more than any of the people that you know in your area.

“You know your area for being full of people who could only buy a Meal Deal for lunch. But then suddenly, there are these kids who want to eat more than a Meal Deal for lunch. And then you’ve got a Pret [a Manger] in your area. That’s a café we’ve got in London, which is the fucking indicator of gentrification. Or say you’ve got a Starbucks that’s opened. And you’re like, ‘What the fuck is a Starbucks doing in this area?’

Advertisement

“And before you know it, developers have come in, and they’ve bought private land,” she continues. “You’ve no control over that. They belong in the top 1%. So then what are you supposed to do? Fight with the top 1%? The whole point of the top 1% is that they’re indestructible. You can’t touch them.”

Alongside these major issues, Skin also finds Joy delving into personal relationships. Having previously addressed her own experiences with depression on the 2020 single ‘Anyone But Me’, she discusses her attempts to reach out to a loved one struggling with their mental health on the new album’s title-track.

“I wrote it for him, because I didn’t know how else to say that his life was worth living,” she reveals. “Again, my natural instinct when I was a teenager was, if I didn’t know how to say something, I’d probably end up writing about it.

“He didn’t know how to take it, though. What would you do, if you felt like you were on the fucking end of the earth, your life is over – and then the person you love comes and writes you a song? It’s strange. You don’t even know how to reply to that.”

Striking a balance between the personal and the political comes naturally to Joy.

“I just go into the studio and write whatever the fuck is bothering me that day,” she explains. “The bother can be a personal political, or a worldly political. Political songs in general are harder to write, because suddenly you’re not just talking on behalf of yourself. You might be talking on behalf of other people’s experiences. Not that you’re trying to represent other people, but whatever you say has affected other people before. So it’s harder to write – and it involves more sources and research and fact-checking than writing about just going to the fucking Burger King with your boyfriend and ordering a Whopper.”

Advertisement

That’s not to say there isn’t a time and place for a Whopper-inspired single, or the unbridled inspiration of a messy night out. Skin’s closing track, ‘Theek Ache’, for instance, was written after some day-drinking with Killing Eve star Jodie Comer.

“We got absolutely shite-faced at like four in the afternoon, drinking loads of Old Fashioneds,” Joy laughs. “She was on the Espresso Martinis. The next day at home, I sat down, and wrote this chord sequence on the piano. It felt like a song that was like, ‘Fuck it’. That’s what ‘Theek Ache’ is – a song about getting drunk, wearing shite heels, and being alright with it.”

With the album release behind her, she’s now facing into a busy few months of touring

“I want to make sure I’m eating well – I say with a fucking bubble tea in my hand,” she grins.

Control, or the lack thereof, is an issue that Joy has clearly spent time meditating on – whether she’s talking about touring, gentrification, mental health or the abuse of power. Over the last 20 months, the Covid-19 pandemic has been the biggest test of all for the artist, in that respect. But within the depths of lockdown, she found her strength by conquering the little things.

“When you’re so out of control, the best way to feel like yourself is by redeeming whatever control you can,” she says. “With me, I kept my music going, and I kept my routine going. I accepted that the world was going a certain way. And I needed to accept that. Because there was nothing I could do to change the world – but I could change my underwear, and maybe change a chord or two, and make a song...”

Advertisement

After that, the rest will follow.

•Skin is out now.

Read more of the 12 Interviews of Xmas here.