- Music

- 04 Jun 19

In 1989, The Cure were still riding high on the success of their 1987 album Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me. That sprawling and ambitious dose of pop-maximalism had marked the band’s first venture into the US Top 40 and produced their most successful single release to date in the form of the exhilarating, ‘Just Like Heaven’. Perhaps, as a reaction to the success of the poppier Kiss Me, their 1989 opus Disintegration saw Robert Smith and his imaginary boys lurch back into the shadows. A much darker, more introspective version of The Cure than their legions of new fans may have been familiar with, Disintegration nonetheless went on to be even more successful than its predecessor. Two months after the album’s release, the late-great George Byrne hit the road to Portugal to see the band in action and to sit down with Robert Smith for his first Hot Press cover story. Also in this issue of Hot Press (Vol. 13 No.14) we caught up with (now Labour leader) Brendan Howlin; talked global success and the Japanese’ love for the Donegal accent with Enya; and we cast our eye over albums by Prefab Sprout, Paul McCartney and The Stone Roses.

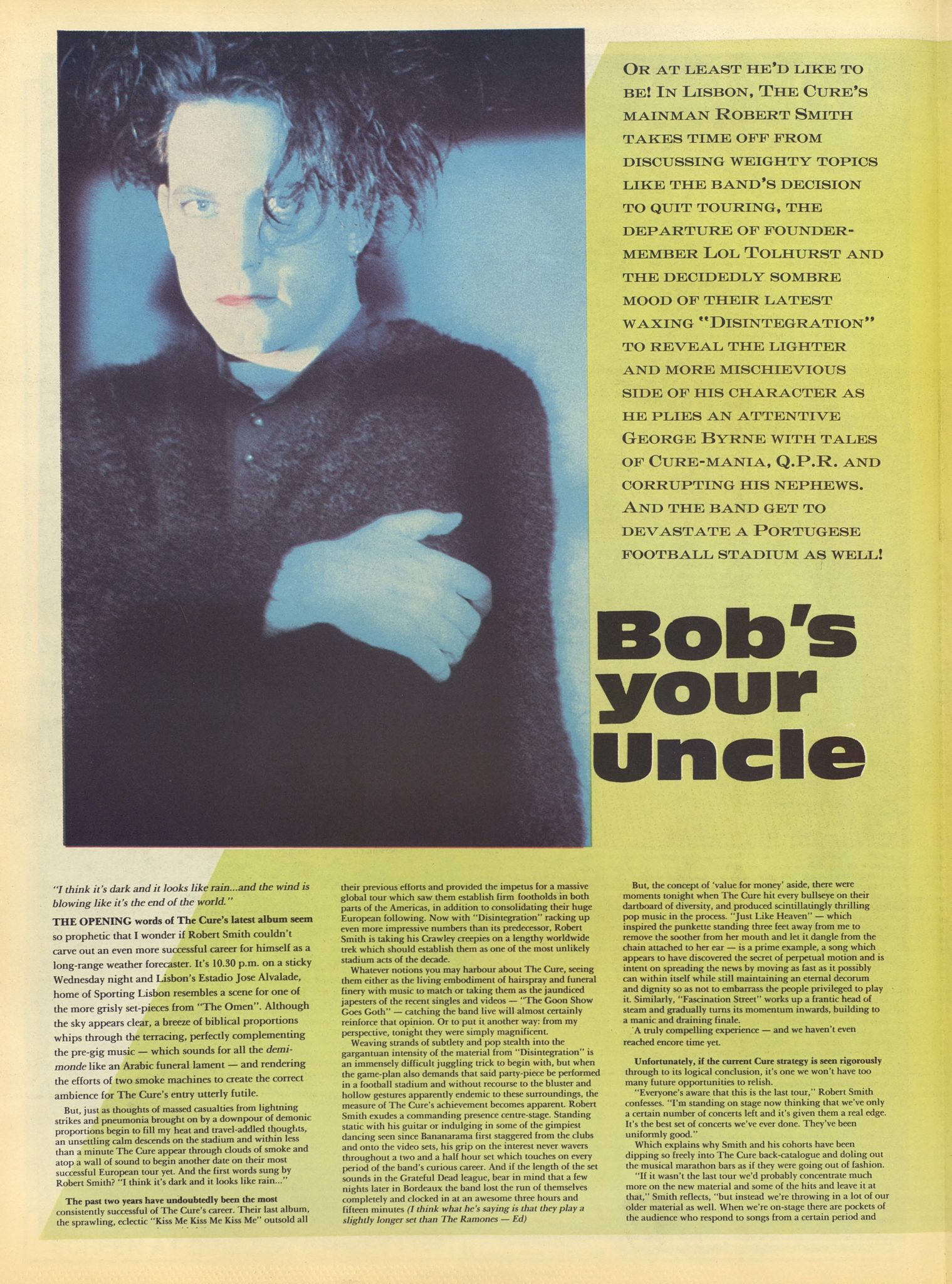

BOB’S YOUR UNCLE

Or at least he’d like to be! In Lisbon, The Cure’s main man Robert Smith takes time off from discussing weighty topics like the band’s decision to quit touring, the departure of founder-member Lol Tolhurst and the decidedly sombre mood of their latest waxing, Disintegration, to reveal the lighter and more mischievious side of his character as he plies an attentive George Byrne with tales of Cure-mania, Q.P.R. and corrupting his nephews. And the band get to devastate a Portugese football stadium as well!

"I think it’s dark and it looks like rain...and the wind is blowing like it’s the end of the world. ”

THE OPENING words of The Cure’s latest album seem so prophetic that I wonder if Robert Smith couldn’t carve out an even more successful career for himself as a long-range weather forecaster. It’s 10.30 p.m. on a sticky Wednesday night and Lisbon’s Estadio Jose Alvalade, home of Sporting Lisbon resembles a scene for one of the more grisly set-pieces from The Omen. Although the sky appears clear, a breeze of biblical proportions whips through the terracing, perfectly complementing the pre-gig music — which sounds for all the demi monde like an Arabic funeral lament — and rendering the efforts of two smoke machines to create the correct ambience for The Cure’s entry utterly futile.

But, just as thoughts of massed casualties from lightning strikes and pneumonia brought on by a downpour of demonic proportions begin to fill my heat and travel-addled thoughts, an unsettling calm descends on the stadium and within less than a minute The Cure appear through clouds of smoke and atop a wall of sound to begin another date on their most successful European tour yet. And the first words sung by Robert Smith? "I think it’s dark and it looks like rain...”

The past two years have undoubtedly been the most consistently successful of The Cure’s career. Their last album, the sprawling, eclectic Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me outsold all their previous efforts and provided the impetus for a massive global tour which saw them establish firm footholds in both parts of the Americas, in addition to consolidating their huge European following. Now with Disintegration racking up even more impressive numbers than its predecessor, Robert Smith is taking his Crawley creepies on a lengthy worldwide trek which should establish them as one of the most unlikely stadium acts of the decade.

Whatever notions you may harbour about The Cure, seeing them either as the living embodiment of hairspray and funeral finery with music to match or taking them as the jaundiced japesters of the recent singles and videos — “The Goon Show Goes Goth” — catching the band live will almost certainly reinforce that opinion. Or to pul it another way: from my perspective, tonight they were simply magnificent.

Weaving strands of subtlety and pop stealth into the gargantuan intensity of the material from Disintegration is an immensely difficult juggling trick to begin with, but when the game-plan also demands that said party-piece be performed in a football stadium and without recourse to the bluster and hollow gestures apparently endemic to these surroundings, the measure of The Cure’s achievement becomes apparent. Robert Smith exudes a commanding presence centre-stage. Standing static with his guitar or indulging in some of the gimpiest dancing seen since Bananarama first staggered from the clubs and onto the video sets, his grip on the interest never wavers throughout a two and a half hour set which touches on every period of the band’s curious career. And if the length of the set sounds in the Grateful Dead league, bear in mind that a few nights later in Bordeaux the band lost the run of themselves completely and clocked in at an awesome three hours and fifteen minutes (I think what he ’s saying is that they play a slightly longer set than The Ramones — Ed)

But, the concept of ‘value for money' aside, there were moments tonight when The Cure hit every bullseye on their dartboard of diversity, and produced scintillatingly thrilling pop music in the process. “Just Like Heaven” — which inspired the punkette standing three feet away from me to remove the soother from her mouth and let it dangle from the chain attached to her ear — is a prime example, a song which appears to have discovered the secret of perpetual motion and is intent on spreading the news by moving as fast as it possibly can within itself while still maintaining an eternal decorum and dignity so as not to embarrass the people privileged to play it. Similarly, 'Fascination Street' works up a frantic head of steam and gradually turns its momentum inwards, building to a manic and draining finale.

A truly compelling experience — and we haven’t even reached encore time yet.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, if the current Cure strategy is seen rigorously through to its logical conclusion, it’s one we won’t have too many future opportunities to relish.

"Everyone's aware that this is the last tour,” Robert Smith confesses. "I’m standing on stage now thinking that we’ve only a certain number of concerts left and it’s given them a real edge. It’s the best set of concerts we’ve ever done. They’ve been uniformly good.”

Which explains why Smith and his cohorts have been dipping so freely into The Cure back-catalogue and doling out the musical marathon bars as if they were going out of fashion.

“If it wasn’t the last tour we’d probably concentrate much more on the new material and some of the hits and leave it at that,” Smith reflects, “but instead we’re throwing in a lot of our older material as well. When we’re on-stage there are pockets of the audience who respond to songs from a certain period and others who respond to the hits, so we're playing to that. We never would have done that before but we’ve reached the point where the only reason to tour is to play to people."

That said, Smith has decided that The Cure shouldn’t hit the road again after ‘The Prayer Tour’ winds up later this year. His reasons for calling a halt are not uncommon — primarily a feeling that a band’s creativity is inevitably sapped as a result of spending over a year being shunted from hotel to venue and back again, not to mention having to say the same things ten times a day to people like me. In the context, Smith is determined that The Cure’s last worldwide jaunt will be remembered by their fans, with whom the band have an unusually close relationship. There’s the curious case of The Camera for example.

“Terry, who looks after us on the road, goes out into the audience with a video camera as they’re coming in and films people,” he explains. “We watch it in the dressing-room fifteen minutes later to see what songs they want to hear, what they look like, how old they are...it’s a bit absurd really. People still throw up requests for songs onto the stage on bits of paper and, if we can, we’ll do them.’’

In Lisbon, as it happens, there is a marked absence of what has become the stereotypical Cure fan, those cosmetically-created consumptives who seem to be silently praying for a plague as — in Dublin — they amble morosely down Grafton Street in search of sanctuary for their tortured souls, only to end up feeding the ducks in the Green. No, here the broad appeal of the band is manifest in a cosmopolitan collection of humanity, encompassing punks, bikers and a host of apparently normal people — including two girls in party frocks, who punctuate their evening by throwing up over a railing. It’s a diversity which Robert Smith can afford to revel in, as long as it lasts, confirming as it does The Cure’s ascension to the front rank of global pop bands.

“It’s always been very difficult talking about our audiences,” he says, "and it gets more difficult as the years go by because I find it’s very easy to be patronising. I listen to Paula Abdul and I listen to Mozart and I don’t see any reason why I should bracket people who come to our concerts into liking one particular aspect of what we do. Obviously they’re divided to a certain degree, between the younger, newer fans and the older ones but judging by the reaction of the people so far at most of the concerts, even the ones who were at school or in nappies when we first played in their particular country really like the old stuff and like to see it being performed.”

It may just be that The Cure have successfully mastered the crucial pop knack of being all things to all people — without damaging their credibility or integrity...

It’s certainly true that Disintegration represented a dramatic mood-change, from the playful pop eclecticism of Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me — back, as Robert Smith sees it, towards the more sombre tenor of their original stomping ground. Here were The Cure ten years on, sinking again into the deep dark waters of despair and emotional degradation, and for the most part taking their newly-won and initially more whimsically orientated pop fans with them.

There’s always been a vicious streak in Smith’s writing, a savagery which was displayed most uncomfortably on the harrowing Pornography, a record I can’t imagine anyone sitting through in its entirety precisely because the music matched the mood: harsh and extremely ugly. On the present album, however, the bleak vision has been deceptively couched in musical surroundings of an almost pastoral nature.

My initial reaction was one of severe disappointment but I’ve gradually been seduced by all of the first side and find myself creeping inexorably onto the flip, though the lyrics don’t exactly incite the desire for a knees-up ("I like you in that I like you to scream but if you open your mouth then I can't be responsible for quite what goes in or to care what comes out” — ‘Fascination Street’). So Bob, lie down and tell me about it.

“There’s obviously a wider variety of moods on Kiss Me but for Disintegration we weeded out the happier elements!” he laughs. “We actually demoed more songs for this album than the last one but at the start of the actual recording I wanted the project as a whole to have more of an intensity, which has translated into a kind of gloom. It’s very difficult to be happily intense, I think. But it’s a lopsided view. It’s not actually representative of how I feel at the moment.”

Which can be taken as an admission that Robert Smith, the Prince Of Pain, the Arch-Duke Of Angst, is actually happy?

“Yeah, but it’s always the way,” he smiles. “In the past, when I’ve felt the need to make a record of this type, like Faith or Pornography, as soon as it’s done I feel much better. But then I’ve got to live with it for 18 months, play concerts and explain it in interviews — it all gets a bit unreal.”

At the same time it’s important for Robert Smith to keep people guessing.

"I’m always very wary of us becoming one-dimensional,” he explains, “whether it be in a lightweight way or by being too intense. But with the Kiss Me album being so popular, and with hit singles and happy videos and stuff, I personally wanted to be involved in something that had a bit more substance to it. I really liked Kiss me, it was good fun, as was the whole two years surrounding it, but I didn’t really want to go through it all again.”

There were mutterings in some sections of the press that part of the reason for the relentless and sombre mood of Disintegration was to recapture ground that The Cure might have lost through their poppier forays of the past few years — ground swallowed up in print and vinyl terms by outfits like The Mission, All About Eve and Fields Of The Nephilim. It’s a suggestion which brings a thoroughly derisive laugh from Robert.

“There isn’t really any rationale behind it. To start off with, I was more concerned about the emotional intensity that was going to be on the record and that necessitates a certain style. For the first time since Pornography, the music was dictated by the words.

"But I never feel in competition with people. I went out and bought All About Eve’s album. I think they’re really good and write great songs. The Mission have played with us on about four bills out here in Europe — we invited them because they’re good live, although I’ve never liked them on record. Just because I’m in a group, I don't feel as if I’m competing with New Order or The Cocteau Twins when I go out and buy their records. I like listening to music and I like playing it. It’s as simple as that.”

Sometimes, it really is...

This bloke goes into the doctor and says ‘Doctor my brother thinks he’s an orange’. So the doctor says ‘Where is he?’ and the bloke says ‘He’s in my pocket’.”

O.K., O.K., it’s not exactly the kind of thing that’s likely to feature in a Steve Martin comedy anthology but it still managed to crack me up — due no doubt in part to the fact that Robert Smith delivered it to several thousand bemused Portugese fans when Roger O’Donnell’s keyboards went briefly on the blink. Humour is a word which rarely occupies the same paragraph as the band’s name but, for all the darkness in their songs, I find that it’s the inherent, although admittedly fairly well buried, mirth which makes The Cure such an attractive overall proposition.

“I don’t give a shit anyway if people get the wrong impression of us,” Robert Smith comments. “I mean, if after a video like ‘Why Can't I Be You?’ people still think we’re sombre then that’s fine for them. There’s a million criticisms you can level at any group if you want to, but I never pay much attention because we just do what we want, I enjoy what we do, and that’s it. We’re lucky in that each time we do something, more people like it than the last time.”

In terms of continuing that process of broadening their audience, one of the unwritten rules for successful bands at this stage would appear to revolve around that most desirable medium: film. There can hardly be a major band in recent years who haven’t at least released a live video, with varying degrees of ambition and success. Depeche Mode lead the pack by a mile with the D.A. Pennebaker — directed 101, which points to how the sporadically-successful Rattle And Hum should have been approached, but The Cure have also pitched their lent in the celluloid circus with 1987’s The Cure In Orange, a concert film directed by the man responsible for their inventive videos, Tim Pope.

“In retrospect I think we could have made more of it,” Robert confesses, “we ran out of time really and no-one was willing to commit an inordinate amount of money to the project. From our point of view we wanted it almost like a well-done home movie of us playing, because it had never been done and I didn’t want to leave it all behind. It was a perfect setting, the group was playing really well, and I wanted the film to be like a memento but it escalated into a full-scale film project that never actually reached full-scale thinking. It works really well in a cinema but a lot of people have said that they prefer watching it at home. Mainly so they can get completely out of it and don't have to worry about catching the last bus, I’d imagine, (laughs).”

If Robert Smith’s evident sense of humour does confound the expectations of die-hard, black-bedecked Cure fans then it’s a process he’s also been carrying through into his personal life.

Recently, Robert married his girlfriend Mary after a courtship of almost Irish duration, some sixteen years. He remains adamant however that his outlook on life will remain unchanged.

"I waited and Mary waited until we’d known each other for longer than we hadn’t known each other, and really I don’t believe in marriage at all — although Mary does, I think. It was just to have that day. The only time you ever get all your family around is either at a funeral or a wedding, unfortunately, and we just wanted that day to remember it — just an old-fashioned romantic day.”

What: Robert Smith an Old-Fashioned Romantic?

"It was the best day I’ve ever had so I must be. I don’t call her my wife, she laughs if I do, and she refuses to call me her husband so it hasn’t really changed anything. She’s kept her own name and I had the ring for ten years before we were married anyway!” he laughs.

Do you think you’d make a good father?

“Some days, but I don’t think I’m consistent enough really. I make a good uncle, or so my nephews tell me (laughs). It’s much more pleasurable being an uncle I think than a father, because you have all of the fun and none of the responsibility. You can actually be the one that encourages them to do the wrong thing and father has to tell them to stop it, ‘don’t listen to your Uncle Robert!’ (chortles).

"I can’t really find good reasons not to do things basically.”

If some key relationships have been coming to fruition for Robert Smith, then others have been sadly unravelling. Throughout their decade in the public eye and ear, The Cure have continually offered something of a moveable feast as regards their line-up, flitting between duo and sextet with scant regard for the sensibilities of compilers of band family-trees. However the last change, which saw them slim down to the five-piece currently on tour, took place at the start of the year and involved the departure of founder-member and long-time friend Lol Tolhurst.

One of the original Three Imaginary Boys, along with Smith and Michael Dempsey, Lol began as the band’s drummer before switching to keyboards. Credited with the enigmatic, ‘other instrument’ on the sleeve of "Disintegration” he now finds himself to be an imaginary member.

“It had been building up for quite a while,” explains Robert somewhat wearily, "really since the Kiss Me album. We got out of sync basically. There’s no acrimony there so it’s a bit of a non-story unfortunately. Everyone was really desperate for some juicy dirt but there wasn’t any. I’ve known him since I was five years old and it would be very difficult at this stage to start getting bitter. Basically, he just wasn’t playing any part in what the group was doing. He was being carried and he was aware of it but didn’t want to do anything about it because he was quite happy just to do nothing...which wasn’t satisfactory.”

Apart from the various musical roles he fulfilled, Lol was also frequently the unfortunate recipient of much abuse from the other members of the band. The butt of any jolly jape that was going, he invariably drew the short straw when it came to being humiliated in The Cure videos, a litany of which is available in the band’s official biography Ten Imaginary Years. So, with Lol gone, who's Robert Smith picking on these days?

"It’s actually worked to our advantage,” he says with alarming enthusiasm, "because we pick on other people these days. It’s like an Us against Them situation again, which is quite refreshing! The other thing is that Lol was no longer filling the need because that need had gone, the actual need for a scapegoat. We exhausted that possibility really, we know each other too well for there to be a scapegoat anymore.”

The Cure’s Us-and-Themness goes only so far however. Sponsorship is one of the eighties most striking off-shoots of rock success, with bands’ uniqueness and individuality often being put in service to less than worthy corporate causes. It’s something Robert Smith would happily become involved in — but only, he stresses, if the right offer came along.

“We have been approached in the past but there’s never really been anyone totally suitable,” he expounds. “We were sponsored in South America by Wrangler but unfortunately the first we knew about it was when we arrived. We didn’t actually get paid, they just decided to put their name over all the posters!

“We did actually try to get sponsored by Guinness on the Kiss Me tour. We wrote them a very nice letter but unfortunately they weren’t interested. We figured that it would be an ideal product to be endorsed by The Cure (makes sense when you think about it — G.B.), and also they were sponsoring Q.P.R. at the time which influenced our approach slightly (laughs). I even mentioned that in the letter but it didn’t hold any weight — and they dropped Q.P.R. the next season anyway!”

An unlikely looking soccer fan Robert Smith may be but he’s a passionate fan of the Trevor Francis-managed London side Queens Park Rangers. The suggestion that he might consider composing a Q.P.R. team song initially produces a bout of manic laughter followed by a more serious response.

“If they asked me, yeah,” he says. "I don’t think it’d be that catchy, but then they’re not that kind of team. The reason I like them is because they’re not like any other team — although the signing of Peter Reid has rather shaken my belief in Q.P.R. at the moment.” But not, apparently, sufficiently to prevent himself and bassist Simon Gallup strolling through Barcelona wearing matching Q.P.R. jerseys and black mini-skirts, an incident over which I feel we should draw a discreet veil as, doubtless, there was drink taken, your honour...

The football connections don’t end with an almost pathological devotion to the lithe leopards of Loftus Road. Back in the Jose Alvalde Stadium, as Smith emerges for the first batch of encores he steps up to the mike and humbly apologises for speaking in English all evening.

“I’m sorry, but I don’t know any Portugese,” he offers, before doing a quick double-take and continuing, "Hang on! I do know one word ‘Eusebio!’ For those of you old enough to remember!” He’s rapidly rewarded for his stunning linguistic prowess as the entire crowd respond to the mention of Portugal’s all-time finest soccer talent by bellowing that magic melody beloved of terrace types the world over ‘Ole! Ole! Ole! Ole! Coo-Ur! Coo-Ur!’ In response the band launch into a stunning sequence introduced by Smith as "pure pop ” with ‘Lullabye’, ‘Close To Me’, ‘Let’s Go To Bed’, ‘Why Can’t I Be You?’, ‘Love Cats’ and ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ following hard on one another’s heels, like six superb home-team strikes.

With the stars twinkling approvingly overhead, the breeze turning the smoke backdrop into a swirling mass reminiscent of the climactic scene from Raiders Of The Lost Ark and a sound both pristine and powerful filling the stadium with some of the most inspired and mischevious pop of the decade the thought struck me that The Cure wasn’t such an inappropriate name for Robert Smith’s lot after all...