- Culture

- 25 Nov 22

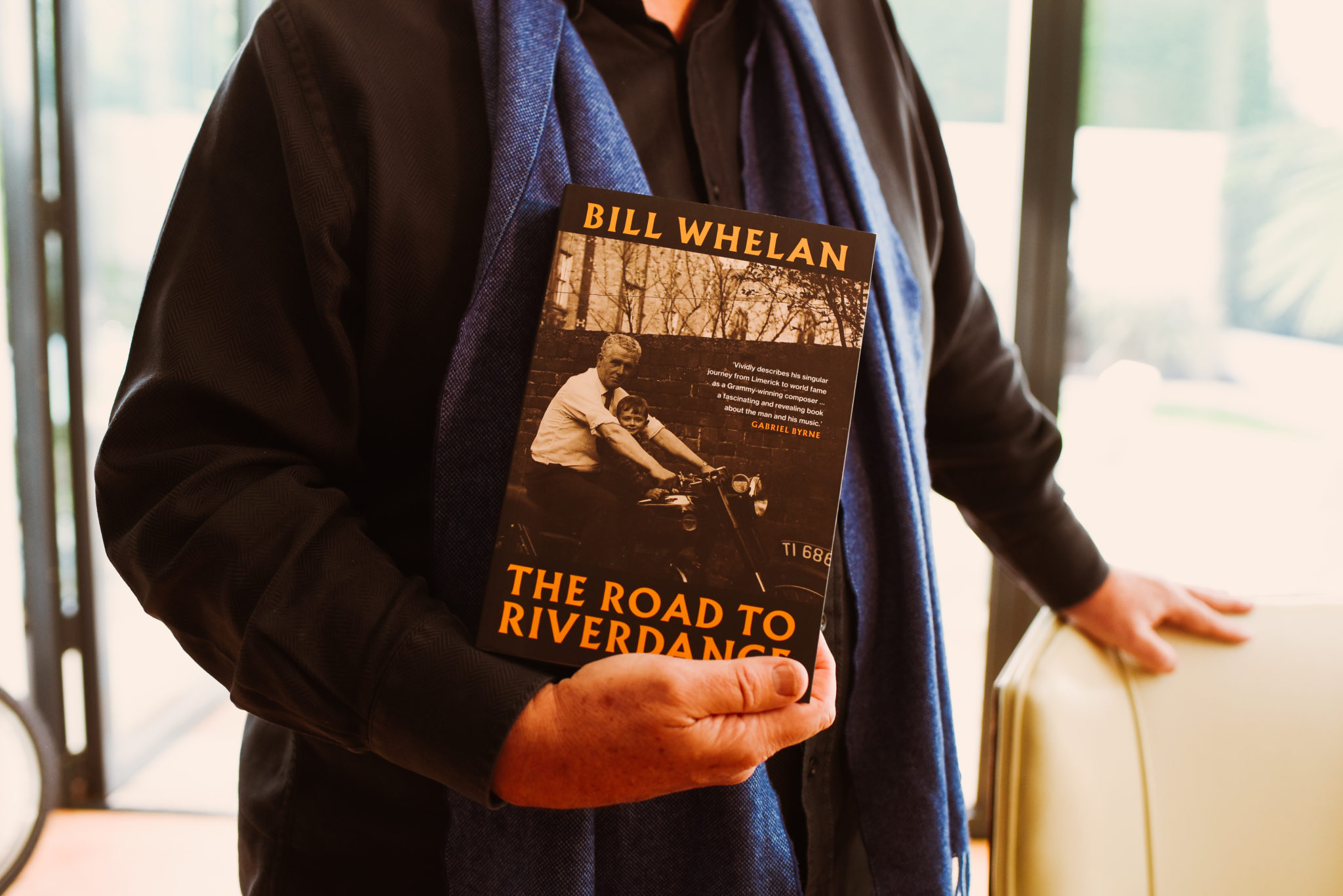

When Bill Whelan started to play drums with two knives and a biscuit tin as a kid in Limerick, he had no idea that he was embarking on a journey that would inspire – and consume – so much of his life and his work. In a career that began in the 1960s, he has worked with some the biggest names in Irish and international music and enjoyed many extraordinary highs – culminating in the global success of Riverdance, the show. Now, in The Road to Riverdance, he has written with fierce honesty about his remarkable, and sometimes troubled, musical and personal journey. Photography: Miguel Ruiz.

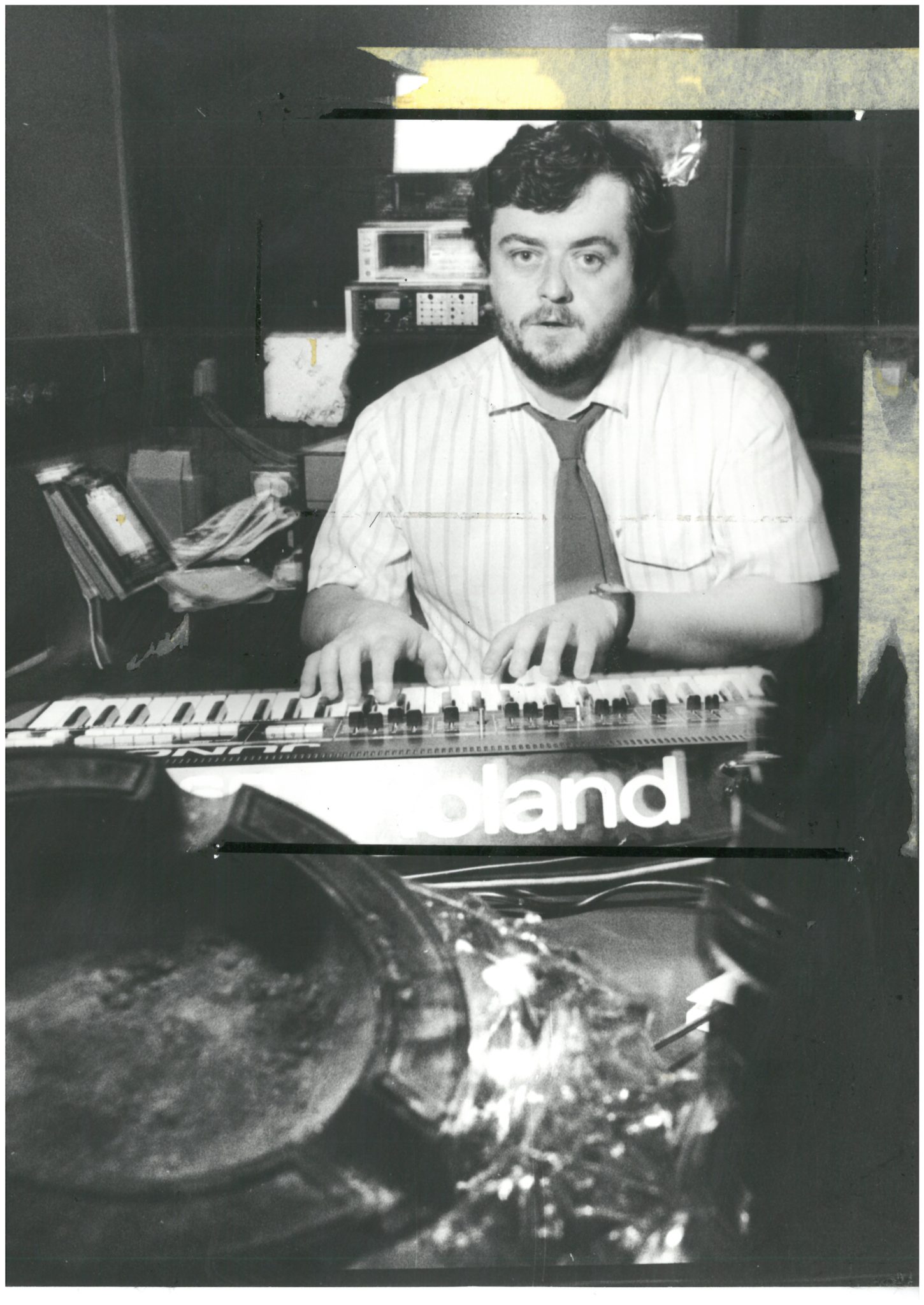

Bill Whelan is among the most important Irish musicians of the past 50 years. During a remarkable career he has produced and arranged records by U2, Kate Bush and Van Morrison, as well as Eurovision-winning performances by Johnny Logan – of ‘What’s Another Year’ (1980) and ‘Hold Me Now’ (1987). He has written scores for major Irish films like Lamb and Dancing at Lúghnasa. He composed original music for fifteen plays by William Butler Yeats, in the role of composer to the W. B. Yeats Festival at the Abbey Theatre.

He was a member of Planxty, produced albums by Andy Irvine and Stockton’s Wing, wrote major orchestral works The Seville Suite and The Spirit of Mayo, and composed the interval music twice for the Eurovision Song Contest, when the final was in Ireland. The first of these pieces was Timedance, written with Donal Lunny, in 1981. And the second was Riverdance, which as a seven-minute virtuoso compositional piece stole the Eurovision show in dramatic style in 1994, spawning the enormously successful full-scale stage version, premiered in Dublin on 5 February 1995, in the Point Theatre (now 3Arena).

Riverdance, the show, has since gone on to win Bill Whelan a Grammy for Best Musical Show Album in 1997 – and to capture the imagination of audiences all over the world. It has been seen by in excess of 25 million people, in the process redefining the potential of Irish dance and taking Irish traditional music into previously uncharted waters.

Bill Whelan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Bill Whelan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Advertisement

Bill Whelan was also heavily involved in the formation and launch, in 1988, of the Irish Music Rights Organisation, which wrested control of the collection and distribution of royalties in this country from the UK-based PRS. Also in the 1980s, he established Irish Film Orchestras, bringing the recording of top level film scores to Ireland and working with stars like Elmer Bernstein, Barry Manilow and Robert Redford, among many more. And, later, he was also involved in the establishment and promotion of Music Generation, a scheme to make musical instruments more widely available for music education in schools all over Ireland.

Inevitably, of course, that kind of breathless summary is only scratching the surface of the surface of a career which has known extraordinary highs, and occasionally severe lows. Which is what makes the publication of Bill Whelan’s autobiography The Road to Riverdance both timely and important. Far too often, Irish musicians have simply faded into the background, leaving their stories untold, and as a result there is scant understanding in the wider world here of just what it takes to set out on the road as an artist or a musician – and to stick with it, come hell or high water. For that, in essence, is what Bill Whelan did...

THEIR POLITICS WAS LABOUR

His wife Denise – perhaps the real hero of the book – had a vital role to play in making it happen.

“Denise had been at me for a while,” Bill confesses with a grin, “to put down a record of my life, for my children and my five grandchildren, so that they’d know a bit about what actually went on. I also wanted to put down a lot of memories of growing up in Limerick and how that influenced the way I went musically.”

Bill grew up an only child, in the centre of Limerick, where his parents ran a shop. His evocation of the sights and sounds of the city is one of the book’s unique strengths.

“I decided to start with the story of Jack Nash, the newspaper seller,” he says. “It brought me right back there. From a very early age, I was conscious of sounds, and the difference in sounds and silences. And what silences in Limerick were like, in evenings and in summer. Birds going around the houses. And people on the street. The musical language of Limerick people was something I grew to love.

“I worked in the family shop, which had a wide range of people coming in and out. So you got to understand people who were factory workers, and how they were different to, you know, the bank manager. Even though Limerick is sometimes painted as being sort of snobby, I was much less conscious of that growing up. I could see that some people were better off than us. People had a car, we didn’t have a car. I could also see that there were people who were clearly in trouble and poorer than us. But it all seemed to be part of the same kind of patchwork of life, and in a city.”

Advertisement

There were times, we learn, when the young Bill would wander off on his own, getting up to divilment of various kinds.

There were times, we learn, when the young Bill would wander off on his own, getting up to divilment of various kinds.

“My parents – and my mother particularly – were very protective,” he says. “So I might have actually just gone off when she wasn’t looking! I wrote in the book about going on the railway line – stuff that’s astonishing now, that you would let children wander around the railway line; and that it wouldn’t seem a bad thing for them to be getting into railway carriages with older men. But to me, it was just a great romance, that we were in trains. And we were blowing holes in walls with pipe bombs. I mean, what was that about?”

He smiles.

“I certainly never experienced anything negative about it.”

Is there a sense that children nowadays are too protected, and that it slows down the process of growing up?

“I think that is absolutely true. Now, it may be that there’s a need for it, I don’t know. But to be able to get up on the back of horses and stuff – there was a freedom to that. Now, you’ll hear, ‘Oh, my God, you could have been killed’ or blah, blah. But we weren’t. And I do think having that freedom to go around and observe and taste and see are all good. They’re really good for the imagination. And you know, I’d much prefer to see that for kids, than just staring into a screen all day.

“My father, I think, was in Leamy School, which is where the McCourts (Malachy and Frank, of Angela’s Ashes fame – Sub Ed) went. And he left probably when he was about 13 and got a job as a fitter. My mother had a longer spell of education. But now, you’re supposed to be making a choice, when they’re in the womb, what schools children are going to go to; what academic path they’re going to go along. It seems to me that an awful lot of the decision making – a child finding out about what they are and where they are – has been taken out of their hands.”

Advertisement

Limerick was known as Confraternity City – was there a pervasive religious influence?

“Yeah, it was a very religious city. The bells would be ringing out in the evening for the men’s Confraternity. And there was a lot of processions up and down streets. I often felt that if you were a non-Catholic, you definitely felt that the civic space was occupied by these people. And you were not part of it. My children are sometimes wide-eyed when I tell them, that when the Angelus rang out in Limerick, things stopped. People got off their bicycles. And they took off their hats. And they said their prayer in the street, no matter what they were doing. It wasn’t like, oh, the nicely, sort of Vaseline Lens stuff you see in the Angelus now on RTÉ, when people are staring off into some kind of metaphysical distance. This was tough. Get off your bike, and say your prayers. If you saw someone doing it now, you’d be ringing somebody to come and check them out.

“There were churches everywhere,” he adds. “Where I grew up, on the next block was the Jesuit church. On the block beside it, that was St. Joseph’s. Then there was ‘the Fathers’ which was what the Redemptorists church was called, which is where the Confraternity took place. I mean, you were never more than a couple of hundred yards from a church. The Sunday masses would be packed. And there was a great sense of the social order, even in the church. I remember seeing Donagh O’Malley’s wife Hilda, about whom Paddy Kavanagh wrote ‘Raglan Road’, who was very beautiful. It was around the time that Jackie Kennedy was very visible – and the Limerick women, of a certain status, including Hilda, would wear mantillas like Jackie.”

The book describes a tempestuous relationship between Bill and his mother. But his father was different, turning the standard narrative on its head.

“My father was just a calm person,” he recalls. “I never saw him really riled. Except one time when he hit me and I peed myself as it was such a shock. Whereas my mother was regularly reaching for the wooden spoon and I’d be whacked around the kitchen and on the legs. Yeah, it was the opposite of the expected thing.

“It’s only with hindsight that I can see what my mother was going through. First of all, she married late. So she had a narrow window to have a family, and then she lost a baby. So when I came along, like, I was only four pounds weight. So, from the very early days, my mother was very concerned about me. When I was a young fella, I was very thin. And she would be worried that I was going to get all kinds of diseases like TB. She was concerned about typhoid. She was terribly nervous about all kinds of things.”

There is a distinct absence of any sense of victimhood in the way Bill tells the story in The Road To Riverdance. But being an only child must have been difficult.

Advertisement

“I felt that I was alone. And then, as I got older, I put on weight and I got quite fat when I was in my mid-teens. And I felt different to other people. As I said, we didn’t have a car. We didn’t take a holiday. The shop never closed, except Christmas Day. And in fact, Christmas Day was the only day my parents and I sat together to eat. The rest of the time, it was me and my father, and then me and my mother. They sat together at night, when he came home from work, which could be 10 o’clock.”

The two sides of Bill’s family were also very different.

“They were all originally Dublin families. My mother was born in Parliament Street. There were ten kids in her family and five of them were born in Dublin and five of them in Limerick. My maternal grandfather was a tailor, who worked in MacBernie’s in Dublin. Then they moved and he worked in Todd’s in Limerick. He was the chief cutter. They were more middle-class and quite secure.”

There was a strong Republican element on the Whelan side, through his grandfather, also called Bill.

“Their politics was Labour. My grandfather was on the first Labour Council in Limerick. My father, and all of them, would have been Labour voters. They left school early, all worked labour jobs or whatever. But their politics were also very Republican in the late 1800s, early 1900s. My uncle Pat, the older brother, was very active. My father was younger, but he was still very active. And they all spoke about the kind of life they led at the hands of the Tans. I would have grown up with a lot of Republican memorabilia and iconography in the house – photos of Sean South – and we sold the Easter Lily in the shop. We sold all the Republican newspapers. So there was a very strong connection.”

THE COMPLETE SONGWRITER

Advertisement

Different as their backgrounds were, Bill’s parents had in common a love of music. It was, as they say, the makings of him. Unusually, he started out as a drummer.

“My father used to play the harmonica,” he recalls. “And I would sit in the kitchen with two knives and a biscuit tin. And I would play. I have a very firm memory of this – the makers on the biscuit tin were Callard and Bowser. And I remember sitting with the biscuit tin and playing along with my father. It got me really interested in drumming and rhythm. There was a commercial traveller who used to come into my father in the shop, and he was an amateur drummer, and he would bring his sticks with him. And my father brought me down to see how you did a paradiddle and how you did a roll. Da da da da. And I was like, wow, this is amazing.”

Bill went through a ‘snare and cymbal’ phase, before his father invested in a kit.

“He was the kind of father who, when he got something, it was partly for you and it was partly because he loved it himself. And so the two of us would play. All that was really important in terms of giving me a love of rhythm and percussion. I played drums in bands then.”

At home – much like Van Morrison’s experience a few years earlier, living in Hyndford Street, Belfast – Bill’s father encouraged him to listen to music that was wildly unconventional.

“My mother, being a good musician, had always encouraged me with music,” he says. “But my father’s taste included everything from Thelonious Monk to things like Dave Brubeck, and all those really interesting rhythms that he was playing. He was bringing that into the house. And I was hearing it and going, ‘Whoa, what’s that?’ I just thought, wow, this is really broad and open. Music – this thing I had in my life – was a free area.”

As a result, when he left to study at UCD in Dublin, he didn’t feel that he was escaping the limitations of life in Limerick.

Advertisement

“We were at a time when there was a great sense of social change,” he recalls. “In the ‘60s, we were hearing and seeing things that my parents never saw. So, we were definitely feeling part of a movement that was going away from that.

“I remember hearing ‘She Loves You’ for the first time,. And even though we’d heard Elvis Presley and Bill Haley and the Comets, there was something that happened with The Beatles. When, rather than just the boy meets girl, they started writing about things they observed and stuff, it was like totally fresh air. You know the way we always divided up into The Beatles and The Stones? I was a Beatles fan. They were a big, big influence on me. From the first time I heard the Beatles, when I was 13, or thereabouts, there really was something exciting happening.

“That led me on into the American end of things, Frank Zappa, and all of that – it was ‘Whoa, what was this stuff?’ And then growing up in Limerick with Granny’s Intentions and Reform. My son is a musician, and he says, ‘You guys, you had all the great stuff’ – and you know, we kinda did. We were living through an extraordinary time that delivered so much really powerful music from Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan on.

“I’ve just finished a biography of Joni Mitchell,” he adds. “It’s extraordinary. She had a whole connection to the folk thing. Then – rather like Dylan with The Band – she moved off with the LA Express and did the Court And Spark album and stuff. But to me she was the complete songwriter. Her lyrics were poetic, and approached things that really resonated for people. But then the music she composed to get those lyrics across was complex and yet accessible.”

Bill Whelan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Bill Whelan. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Bill talks about the aneurism Joni suffered in 2015, and the fact that it was three days before anyone found her.

Advertisement

“That knocked me off my feet,” he says. “It was just incredible that this extraordinary woman, who had an unbelievable life and more partners than you and I’ve had hot dinners – Leonard Cohen, David Crosby, Graham Nash. James Taylor, Jackson Browne, Larry Klein, all these men that she had during her life – and yet she lay on the floor for three days before anyone discovered her.”

In some ways, it took Bill time to adapt to college life.

“I believed things that I’d picked up through religion and through education,” he remembers. “And suddenly in 1968 and ‘69, the early days of a kind of a revolutionary period, in my first and second year in college, I was exposed to things that I would not have seen in Limerick. I remember feeling nervous about it. It took me a while to examine it without fear. Just hanging around with other guys in college, and then going to meetings and to sit-ins and all that happened in the late ‘’60s, early ‘70s – that was challenging, but it was also liberating.”

He was at the demonstration that led to the burning of the British embassy on 2 February 1972, in the immediate aftermath of Bloody Sunday, when the British Army shot 26 innocent civilians, killing 14 in Derry.

“I remember it very well,” he says. “I remember gathering with the enormous crowd at Merrion Square. And watching as the first sign of, I guess it was a petrol bomb or something, and the guys climbing up in the windows and stuff. We all felt the same. We felt angry. And I thought it was smart of the authorities to kind of let it happen. It almost was the safety valve. And, I mean, nobody died. But the building was wrecked.”

In the long run, the republicanism he had learned at home became more complicated.

“Particularly in the trad music scene, there was a strong association with, shall we say, the struggle in the North, and you were expected to take a position. I remember playing with Planxty, in Belfast, and we were escorted in and out of the venue by people who were obviously not officers of the State. And I felt a strong sympathy – it was the kind of message that made sense to me from where I came. But I still had the ambiguity that Paul Brady refers to in his book – we didn’t see what role music had in this. And because the arguments were quite subtle, I was very cagey about where I stood. While I was sympathetic to the hunger strikes, I still couldn’t make the jump to blowing up people in the street. And I still can’t, you know?

Advertisement

“The number of people who died in Northern Ireland in our lifetime, just because they were unlucky enough to be standing beside that car, or in that shop, or whatever. I still retain a hope in Martin Luther King’s great dream of learning to live together as brothers: ‘We’ve learned to fly the air like birds and swim the sea like fish. But we haven’t learned the simple art of living like brothers’. And that really bothers me. And we’re looking at it in Ukraine now. I’m not a hippie in the sense of Back to the Garden – but we must have something better than just killing people in their homes. For what?”

Amy Mae Dolan and Bobby Hodges dancing at the Riverdance gala performance at 3Arena. Sunday 9th of February 2020. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Amy Mae Dolan and Bobby Hodges dancing at the Riverdance gala performance at 3Arena. Sunday 9th of February 2020. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.YOU’RE NOT KATE BUSH

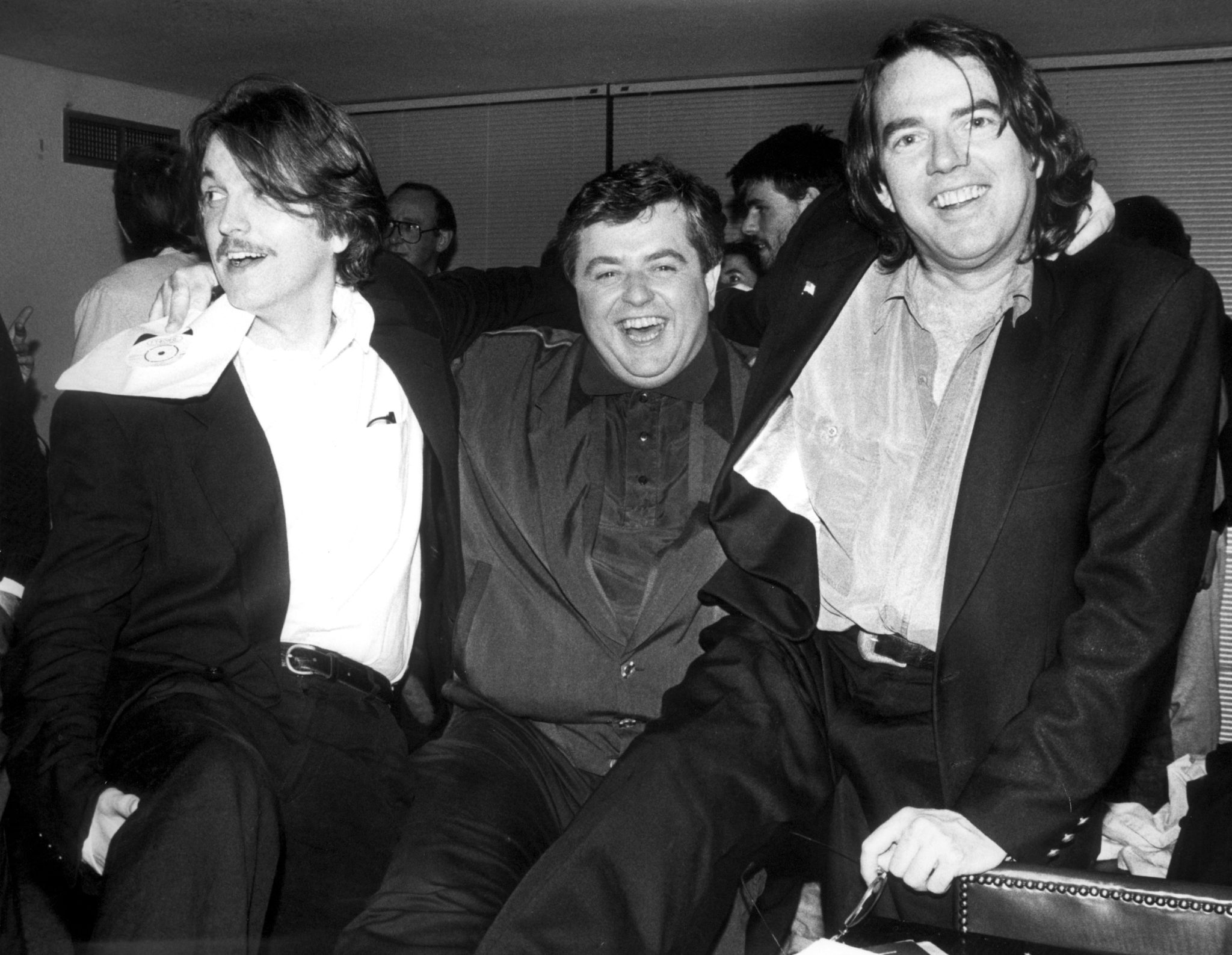

Straight outta Limerick! Bill Whelan’s first big musical adventure happened when he was a law student – not that he was the most diligent fella in the class – and it involved a famous Limerick actor.

“I was still going around walking into studios,” he admits, “knocking on the door, and saying, ‘Can I come in?’ Trying to find a door, either literal or metaphorical, that would get me into the music industry. And I was writing songs. And then one of several songs made it to Richard Harris’s office in London. And the next thing, I got a call to say that this piece of music I had written was going to be the theme for a Richard Harris movie, called Bloomfield.”

The year was 1970.

Advertisement

“You can imagine what that was like at 19 years of age,” he says. “I was sent an airline ticket to come to London. Niall Connery, who wrote the lyrics, and I were flown to London, met by a Rolls Royce, brought to parties, with Christine Keeler (the sex worker who achieved notoriety for her involvement in the Profumo scandal), The Bee Gees – Jesus, it was enough to turn anyone’s head. The film came out – Romy Schneider was in it. There was a premiere in Limerick – and then nothing happened. The film died. I thought it was in the fast-track lane to the music business. Instead, it was back to studying.”

A lot of people in rock ’n’ roll at the time, including Philip Lynott and Bob Geldof, viewed showbands as the enemy. Bill saw it differently.

“I would say that if you’d talked to any of the people who came through the showbands, like Arty McGlynn or Des Moore, or Dessie Reynolds, they learned their musicianship there. They had a really tough life. Those guys were going out on the road every night of the week and travelling from Dingle to Antrim, you know, and playing a lot of the stuff that they didn’t particularly like. But it was fantastic training.”

He was faster than most to understand that you could sell songs – with The Freshmen among those who bit.

“I’d never had an ambition to be upfront as the singer in the band,” he explains. “I just wanted to be like the people I admired – George Martin or Bones Howe. And the composers. A lot of the artists didn’t write songs in those days – they picked up songs from Holland-Dozier-Holland or whoever. The writers were there, and they were feeding the industry. So I thought: could I be that? The Freshmen recorded one of my songs, ‘Say You’re Sorry’. And The Pattersons, a ballad group, recorded one of my songs. And I just felt – that’s what I wanted to do, to get my songs away and be a songwriter, or a composer, that people will go to.”

Easier said than done.

“I remember taking my tapes around the record companies in England,” Bill recounts. “They’d listen to about 10 seconds of something and then say, ‘Roll on the tape. Yeah, well, we’ll give you a call’. And you felt really demoralised. These people were making the decisions. And you were just back out on the street. And even if a guy was chatting to you, he’d start telling you Irish jokes. It was tough. The condescension, the fact that they were looking at the showbands, and thinking that’s what Irish music is about. And they were saying, well, nothing any good will come out of that. And it was extraordinary how that turned around after the late ‘70s, and suddenly they were all coming here – after Windmill Lane and U2 and all of that.”

Bill was instrumental in driving the shift in perception, when he produced Johnny Logan singing the Shay Healy song ‘What’s Another Year’, which won the Eurovision Song Contest in 1980. Was there a sense then that the legendary sunny uplands beckoned?

Advertisement

“Shay sold us all on the sunny uplands! But, for me, with ‘What’s Another Year’, I had a No.1 record in the UK. That was ‘Wow!’ And then CBS were coming back to me to produce The Sutherland Brothers. And it looked like things were coming along nicely.”

Amy Mae Dolan and Bobby Hodges dancing at the Riverdance gala performance at 3Arena. Sunday 9th of February 2020. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Amy Mae Dolan and Bobby Hodges dancing at the Riverdance gala performance at 3Arena. Sunday 9th of February 2020. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Not on every level, mind. I’m thinking of the “Produced by Nicky Graham und Bill Whelan” incident...

“I’ll never forget it,” he laughs. “Because up to then Nicky Graham had been all sort of ‘Oh Bill, yeah, you got rid of Dave Pennyfather off the record in Ireland’. And I said, ‘Yeah, it was a bit embarrassing, but you know, it’s turned out fine’’. You can look back through Music Week over those three weeks: ‘What’s Another Year’ came in at No. 15 – and it had ‘Produced by Bill Whelan and Dave Pennyfather’.

What? And then at No.3, it’s produced by nobody. There’s no producer. And at No.1, it’s: ‘Produced by Bill Whelan’. And in those two weeks, there had been lawyers talking. So Nicky was all, ‘Yeah, well done, Bill’. And then – at his invitation – I’m riffling through his record collection in his office. I pull out one, and it’s the German release of ‘What’s Another Year’ – and it says on the label ‘Produced by Bill Whelan und Nicky Graham’. And I just thought: this industry will never cease to amaze me.”

There’s a chapter in the book entitled U2, Minor Detail and Dickie Rock. Bill produced ’The Refugee’ on the War album, released in 1983.

Advertisement

“That’s the book right there,” he exclaims. “The U2 session was amazing, because you could just feel the energy. It was the War album. And, you know, they’d already taken off, but they were starting to put on the afterburners, and it was really exciting to work with. Because of my background, and all the things we’ve discussed – folk music, orchestral music and everything – and here I was working with a rock band. I know, I did people like Paul Cleary, but this was like THE rock band. And this was the band that was going to put Ireland on the map. And that was incredible.”

Minor Detail – comprising John Hughes, who later managed The Corrs, and his brother Willie – were also a bit of a phenomenon.

“It was a direct signing from America, which was unheard of here at the time,” Bill recalls. “The A&R guys were flying in. One flew in on Concorde. And they were sitting in the studio waiting. We were a little bit theatrical – like we’d keep them out in the greenroom for a while. And then we’d bring them in, ‘Yes, you can sit and listen to two tracks, but we’re very, very busy’ – that kind of stuff. One guy from CBS said, ‘I’m listening to the new Simon and Garfunkel’. So they had the choice of any record company in America. Not before, nor since, have I ever seen that level of excitement.”

It’s an old record biz story. The A&R guy in the record company that signed them was fired.

“He was taken out by security,” Bill grins. “And his desk was emptied. I don’t know the circumstances, but they lost their champion. And then it fell apart. And then there was Dickie Rock. It seems an odd collection of people – but that’s the way my life was. My life was all about do this, do that. And I had the skills and I could do it. But I was unfocused still at that stage.”

The work that Bill did with Kate Bush remains a stand-out moment.

“Kate really was the strongest, yet most gentle presence in the studio and great fun,” he reflects. “I did three albums worth of work with her. And we laughed as much as we worked. We had all these little private jokes and stuff that she did. She’s quite mischievous with her humour, but you know, the public image that you had didn’t appear.”

Advertisement

Photograph: United Archives GmbH

Photograph: United Archives GmbHBill looks around the kitchen of his house, where we’re talking.

“We used to have a surround on the fireplace,” he says, “which Kate was sitting on. And my son Brian, who was about four, came in and I introduced them. I said, ‘this is my son, Brian, this is Kate’. And she said, ‘Hello, Brian’. She was very sweet. And he said, ‘Who are you?’ And she said, ‘I’m Kate Bush’. And he said, ‘Hmm’. And then he went out that door. And we were still chatting at the fire when he came back in holding the Dreaming album. And he sat down beside Kate Bush again. And he looked at the photo on the Dreaming album, which is Kate, sort of, obviously in a kiss or about to, and she’s got a ring, like a wedding ring, on her tongue. She looks beautiful. And, here, she was in jeans and a jumper. And he looked at her and he looked at the sleeve. He looked at her again. And he said ‘You’re not Kate Bush’. And she was knocked out with that. She was great to work with.”

She is often depicted as quintessentially English – but Kate was interested in exploring her Irish heritage.

“Her mother was from Waterford. And her brother, Paddy Bush, was a great collector of music from all kinds of places and he was a big fan of The Bothy Band. So he certainly would have introduced her to a lot of Irish music. And, you know, an individual like him would have gone deep into Irish trad music and exposed her to quite a lot of stuff. So she felt a kinship with Irish music. She loved working with Donal Lunny as well.”

MUSICAL AND CULTURAL LEGACY

Advertisement

If Bill felt that he lacked focus during the 1980s, he was about to find it. In The Road to Riverdance, he is unflinching in his discussion of alcohol, and the impact it had on his life.

“I’ve never talked about alcohol before,” he says. “Never talked about my family and my relationships – they’ve always been private things. And this is a little bit exposing. And I’m not madly comfortable about it. But at the same time, the long and short of it is, I feel at this age, I want to put it down. I want to write about it.”

In the book, he tells a story of driving the wrong way up Dawson Street and being hauled before the court. It was a mortifying experience. The judge, as it happened, was an aunt of his. Whether she recognised him or not, he never knew. She banned him from driving either way.

“It crept up on me,” he says now. “Like, if I turned up to a recording session, and I’d been drinking the night before, nobody batted an eyelid. Because everybody else had been drinking too, you know? And you’d go and have a pint at lunchtime and come back into a session in the afternoon. So there was a big acceptance of it.”

At home, he’d sit up playing music and drinking into the wee small hours.

“I’d still be there, at the old stereo, till two or three o’clock in the morning, having brandy after brandy listening to the LA Express or whatever it was, using it as a soporific, as some way to dull myself.

“Then, suddenly, I was having to have a drink to sort of steady myself. And then I went through all the usual like, ‘Oh, you’ve got to stop and only drink on Fridays, only drink at the weekend’, and all the other nonsense. Once that thing has got a grip, there’s only one way and that’s to ungrip it. And it took me a while and a bit of occasional relapsing. But I haven’t had a drink in a good while now. And I’m much, much happier. And as I said to you earlier, if I hadn’t stopped in ’89, none of those things would have happened. Not The Seville Suite. Not Riverdance. If I had kept drinking, I wouldn’t have done those things. I have to acknowledge that.”

Advertisement

It can’t have been easy making the decision to write about it.

“I spoke to Denise and I talked to the kids and said, ‘Look, I’m going to write about this, but I’m not going to publish it unless all of you are happy’. And they said, ‘Yeah, absolutely. And we’re proud if you go out and talk about it. Because people need to hear it’. I was talking to Adam Clayton the other day and he says the same: you kind of have go out and just talk about it, which he has done. The first step is to admit it to yourself, that you’re a bit out of control. And then to accept it: to say, well, this is me now. It’s not anyone else. I have to deal with it.”

He did. And Riverdance followed. When he was composing what was to become his signature achievement, was he hearing the dancers footsteps in his head?

“I was hearing the rhythms. What I was trying to do with the original seven-minute Riverdance piece, was to create music that would sound Irish, but would be rhythmically challenging for the dancers. When we did it, as the centrepiece, there was a slip jig. And then there was a piece with mixed rhythms, a reel and a jig together. So the reel is in four, and the jig is in three, and seven. And 6/8, 4/4 was where it ended up. I deliberately did that, because I felt, as dancers, they’d feel that this was something unusual, and they would have to invent steps to fit it. And then when we released into the full jig at the end, it was like: we’re coming down the track here, there’s nobody stopping us. But the tension was set up In the piece by the 6/8, 4/4.”

Michael Flatley and Jean Butler choreographed their own steps. And then came that dramatic finale with the line of dancers giving it their all, in marvellous unison.

“That line is the thing,” Bill says. “It was the creation of Mavis Ascot, who I’d worked with on Pirates of Penzance and HMS Pinafore. The dancers all do bits and pieces and then, suddenly, the line forms for the finale. And it’s like, WHOA! Still to this day, you get that rush. Riverdance was a real collaboration between the music – which had to happen first – and then what happened with the choreography and the line. We were so lucky that we had Mavis and so lucky that we had Michael.”

Advertisement

It was the producer Moya Doherty who had to dispense with the services of Michael Flatley just before the show opened in London. Was Bill unnerved when that happened?

“No,” he says. “Because I always believed that that it didn’t matter who danced it: Riverdance had enough power in it to survive, even losing somebody like Michael. And that was subsequently proven. Moya made the call. And she rang me on the day that she finally decided to let him go, and said, ‘I’m gonna let him go, what do you think’? And I said, ‘Well, I think we have a decision to make: whether we have a star, or we have a show. And I prefer to think of us as having a show, because the star would only last for a certain time anyway. And the music and the choreography is there for as long as it’s popular’. And here we are 27 years later, and it’s still out there.”

It brought him into contact with a different level of success – and its effects.

“The night that he left, which was the opening night in London, was a bit challenging to everybody’s nerves. Success is an extraordinary thing – and what it does to people. It’s interesting to watch all of us who’ve had a tremendous success in Riverdance – and to observe how we have or haven’t changed, or what it’s done to us. When I met him first – he would come into this house – Michael was an extremely shy, self-effacing guy, you know, polite in that American way of politeness. And then gradually he was playing to 5,000 people a night – it’s really only the strongest character that can not start to think that they’re responsible for the whole thing. It’s really requires a strong person to stand back and say, well, maybe this is not all me. So Michael was gonna go, no matter when it was. I’m happy that it happened when it happened, because the earlier we knew that we had a show, the better.”

We have covered the issue that arose between Bill and Moya Doherty (producer) and John McColgan (director), in relation to Riverdance credits before in Hot Press. In a sense, Bill was still the guy who had to fight his own order.

“It came as a bit of a shock to me, when I began to realise that I was actually being regarded as outside the core of Riverdance,” he says. “I thought I was in there, but when I gave out to Michael, when I thought he behaved unprofessionally – and I was whacked out at that stage, working every hour of the day – I was carpeted by people who I thought were my partners. Who could have said to me, ‘Listen, go easy on Michael’. Instead, they told me never to speak to the star of the show like that again. I kind of thought, hang on, I thought I was a partner here. It was really hurtful. And so yeah, I did feel isolated.

“I never had independent PR. It was always handled by the company. And consequently, my role – if you look at the earliest tickets, it was Riverdance composed by Bill Whelan. And that was it. That was gradually taken away. That was very unusual. In the entertainment business, the composer gets the credit. And that crept in, over the years. And that did make me feel: I thought I was in the tent. I wasn’t.”

Advertisement

That said, the musical and cultural legacy of Riverdance is undeniable, with a great opening up taking place here, inspired at least in part by Bill Whelan’s own experimentation.

“The great hope I see now,” he says, “is in the young Trad musicians, people like Hayley Richardson or Tara Howley, or whoever, who love the tradition, and who play the tradition, but are not afraid to improvise, experiment, listen to other music. They don’t have to immerse themselves in an exclusionary way in the culture – they can be of the culture, love it, and still listen and move out.”

A similar process has happened in Irish dance.

“The rules that bind Irish dance can be narrow, and that’s why I always wanted to have the Spanish and the Black Tap and the Eastern European elements in Riverdance. And of course it had an influence. The Irish dancers who have been working with Spanish dancers, working with Eastern European dancers, with black tappers, they’re examining their own modes of expression. And they’re saying, ‘Well, hang on, if we move a little bit differently, we can do this’.

“From the earliest days in Riverdance, to watch the Irish dancers looking at how the Russians would work out, how they do their physical exercises, even that had an immediate result. As a result of that mixture – with Flately, Butler, Mavis Ascot, all of that melange of stuff – Irish dance developed from being something that you did in a competition, or that you did in the kitchen, dancing around together, into a piece of theatre.”

Which sounds like a good place to end the story for now. Was it hard writing the book?

Advertisement

“I had a regimen. I’m inclined to rise early, so I got up and I was at the desk at six or 6.30am every day, and I would write till after lunch. And, in a very curious way, I began to have the same relationship with what I was writing on the page, as I have when I’m writing a piece of music. You might get 16 bars done some days, you might get two bars done another day. But it’s in your head, and when you go to bed at night it’s still living in there. That surprised me. I didn’t expect that to happen.”

But it did. And the resulting book, The Road to Riverdance – all 300-plus pages of it – makes for marvellous, revealing and very powerful reading. A brilliant addition to the canon, it offers a remarkable picture of a musical life lived to the full.

Hats off to its maker.

• The Road To Riverdance is out now, published by Lilliput

Read more music interviews in the new issue of Hot Press, out now.