- Music

- 01 Aug 23

Blur: "Every band had to have a political agenda, and there was this sixth form outlook on whether the bands meant it or not"

Back with their latest masterwork, The Ballad Of Darren, Britpop heroes Blur talk reinvention, Irish memories, ’90s chaos, Elvis, The Pogues and a whole lot more.

Summer is often known as the silly season in news media, but on the Saturday morning I’m due to meet Blur in Dublin city centre, it’s the opposite of a slow news day. The Ryan Tubridy payments controversy continues to rage – leading to Oireachtas hearings the following week – while in Russia, the Wagner group has commenced its ill-fated rebellion against the Russian government.

Remarkably, by the time Blur take to the stage in the grounds of Malahide Castle later that night, a truce has been brokered by Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, who’s also invited the Wagner leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin, into exile. Such tumult seems an especially long way away when I arrive in a virtually deserted Grand Canal Square, which is basking in glorious summer sunshine.

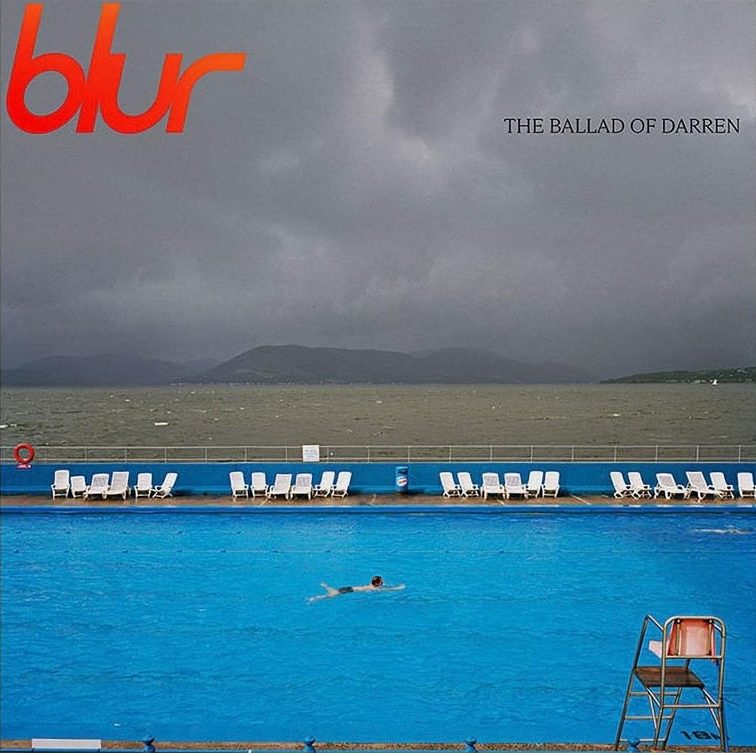

In the close-by Marker hotel, I’m greeted by a rep from Blur’s record company, who tells me the band will be down shortly. The brief wait allows me to focus in the reason we’re here: Blur’s ninth album, The Ballad Of Darren.

Their first LP since 2015’s The Magic Whip, it’s another brilliant collection of buzzing art-rock, catchy pop and elegiac ballads, confirming that the ever-prolific Damon Albarn’s quality control remains exceptionally high.

It also maintains Blur’s uncanny, career-long ability to capture the zeitgeist, whether on the withering social media commentary ‘The Narcissist’, or on the unsettling likes of ‘St Charles Square’ and ‘Barbaric’, which reflect the fraught times we live in. Another track, ‘Russian Strings’, gets its live debut at the Malahide show, with Albarn explaining that the day’s dramatic events prompted its inclusion in the set.

Eventually, the allotted time arrives and I’m led through to a quiet corner of the hotel lobby, where Blur’s guitarist, Graham Coxon, and drummer, Dave Rowntree, are sitting comfortably at a table. Though Dave and I have never met before, I first met Graham – frighteningly – almost 20 years ago at the Village in Dublin (now Opium Rooms), when he was promoting his solo album Happiness In Magazines.

I’ve also interviewed him a couple of times since, most recently last summer for his fine memoir Verse, Chorus, Monster! It’s here where I choose to start. At the end of the interview, I asked the inevitable question about a Blur reunion and a possible new album, to which the guitarist replied, “Probably in another five years or something.” I think it was the following day when the first “Blur to play Wembley” rumours surfaced.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry!” protests a contrite Coxon.

“For years, there had been vague plans to do something,” notes Dave. “For one reason or another, between the pandemic and so on, it just wasn’t possible. Then all of a sudden, I think the Wembley authorities took pity on us, and they agreed with the local council that they could release some more dates for bands to play. They rang our agent and gave us first dibs on one of these dates.

“So it went from, ‘Oh god, another year gone by with nothing happening’ to ‘Wow, we’ve got a date! And we’ve got to put the tickets on sale on Friday!’ Meanwhile, the office is on holiday and everybody’s on tour!”

Wembley would be Blur’s biggest headliner to date, and Graham alludes to the nerves he felt.

“It was pretty anxiety inducing,” he reflects between puffs on a vape. “Wembley stadium is big, so you’re going, ‘Can we do it?’ But it was like, ‘Let’s have a go and see if we can.’ In a healthy way, it was amazing that it sold out.”

The Wembley show was announced at the end of last year, with more live dates – including Malahide – quickly following. Given that the band had to rehearse the tour and assemble a live production, it was no mean feat to complete The Ballad Of Darren in the short time available.

“Something had to give, and in the end, it was rehearsing the tour,” laughs Dave. “We didn’t really do enough of that! But there wasn’t much time, and that’s why it was an open question as to what we’d do. We usually do some recording, so I was pretty confident we’d do something. But by the time we got to January, in order to get the album out by the end of the tour, we’d have to finish it in a couple of months.

“That’s not long at all, and we’d never really made an album in that short a period of time before. I don’t think it was a given that it was going to work out really. We had to come up with the goods pretty quickly and everything had to be right first time.”

Some artists make a virtue of speed in the studio, with David Bowie famously knocking out brilliant work at a dazzling rate. At the other extreme, Leonard Cohen would angst interminably over his compositions, especially the lyrics, sometimes for years at a time. Albarn and Blur definitely seem to lean toward the Bowie approach.

“In some respects, having deadlines can be quite creative,” suggests Rowntree. “You’re forced into making decisions and being assertive. The worst feeling is being stuck in that thing of, ‘Oh god, is this any good?’ You can sit in that forever. My Bloody Valentine have spent god knows how long on some records.”

“If you ask to ask if it’s any good,” adds Coxon, “it usually isn’t.”

“Well, I don’t know about you,” says Dave, “but I get crises from time to time going, ‘Maybe this is complete rubbish. Why have we even started to do this?’ That struggle with the blank page can just eat up pointless time. If you’ve got a deadline approaching, you’ve got to do something. You’ve got to do it now and it’s got to be good.”

Ideally, Graham says, he might have liked a bit more time with the album.

“In a perfect world, I’d like to have listened to what we thought was the finished record for another month,” he considers. “And then gone, ‘Hang on, let’s maybe do this.’ But getting things down the way we did was good for the spontaneity, and what happens when you’re going over and over the songs, and feeling your way through them.

“Stuff happens that you don’t know is going to happen. Getting things all tidy is a little bit boring too, so the Leonard Cohen approach, taking ages over it, is unnecessary. It’s like, do it and write something else. You can right your wrongs on the next album.”

ACCEPTABLE IN THE ’90s

The first gig I ever went to was Blur at the Point Theatre (now 3Arena) in November 1995, when they were touring The Great Escape. Recently, I saw for the first time B-Roads, a documentary on that period that went unseen for decades, but has recently surfaced online.

In between live clips and behind-the-scenes footage, the film takes some unusual diversions (hence the title), visiting suburban swingers and demolition derbies designed to keep teen joy-riders occupied. When I bring it up, Graham has forgotten the film and Dave has to remind him of the details, telling him, “It’s leaked onto YouTube.”

“Oh no!” cries Graham.

“It’s actually quite good,” says Dave. “At the time, we thought it was awful.”

It’s certainly a fascinating document of the ’90s, which leaves you wondering what the hell we were all thinking back then. Certainly, in a more tranquil socio-political era, the luxury we had to focus on bullshit was incredible (when I make this point, Dave erupts with laughter).

At the time of that ’95 Point gig, Blur were enjoying the first flush of superstardom, having beaten Oasis in a colossally hyped chart battle that summer, before scoring another mega-hit with The Great Escape, the follow-up to their era-defining third album, Parklife. They’d also become the first Britpop stadium act when they played Mile End in London, in addition to performing a famous headlining set at Feile in Cork’s Pairc Ui Chaoimh.

The band were most definitely in the eye of the hurricane.

“It was our first time being terribly fried and exhausted,” says Coxon. “And not quite knowing how to deal with that, I suppose.”

“It’s very different from the inside,” muses Rowntree. “Because I was living through it with the same people, doing the same things every day, I didn’t really get a sense of the import of it all until much later. You get very fixated on what the music press is writing about you that week and it’s very hard to see the big picture.

“A symptom of that is that almost all the ephemera to do with a being in a band simply got thrown in the bin, like the stage sets, the lyrics and that kind of stuff. It just got chucked away, cos it never occurred to us that at some point in the future, that would be the history of the band. At the time, the pace of everything just got more and more frenetic.

“The days got longer and the sleep got shorter. We’ve never recovered from that really, it’s stayed with us for the rest of our lives.”

At this point, a comedic dimension to the interview unfolds – a bird flies into the lobby of the Marker and swoops in low over the Blur duo, before fluttering around on the floor beside a nearby table. As I ask my next question, a man chases the bird around in the background, trying to corner the creature so he can release it outside. Forget Spinal Tap – this is Spinal Flap.

Forging ahead, I explain that I first became a Blur fan in early ‘95, when they delivered an electrifying performance of ‘Girls & Boys’ at the Brits, where they won a record four awards and went truly supernova.

“That’s great,” nods Graham as I relay the memory. “We were certainly trying to tear it up – we kind of knew that what we were doing was really good. But we also had a good idea of how absurd it was. It’s complicated. In a lot of ways, we were these scruffy oiks taking the piss. But obviously, we very serious about the music we were making, which in itself was a more artsy piss-taking.

“It always surprises me how scruffy the ’90s were. Maybe it’s so just different to how things are now, where everything is so perfected. It’s all about the business and looking good. I was watching the Arctic Monkeys at Glastonbury last night, and it’s really a lot of style. We’d chuck on a filthy old Fred Perry, some scruffy jeans, and a pair of desert boots or Vans.

“They were our working clothes and we would just play like our lives depended on it. But we were coming from a school of rock and roll that preceded us, and that’s not happening with bands now. We were coming from punk rock, new wave, The Who and those ’60s people we were all into. So it’s a completely different set of ideas, performance-wise.”

Thankfully, our avian friend has now been released by Blur’s security guard, also called Dave (“Wash your hands,” Graham advises him). Returning to our chat, another notable aspect of the ’90s was the cutting tone of the UK music press. They routinely published caustic reviews, albeit underscored by the kind of biting humour that’s now almost entirely disappeared from cultural criticism. I sometimes wonder if the critical climate of that decade forced bands to try harder.

“It definitely skewed what bands did,” says Dave. “When we started out, there were three, and there had just been four, weekly broadsheet music papers, all of which were desperate for – oh for fuck’s sake!”

I look up and see that another bird has flown into the lobby and over our table. There seems to be a flock nearby under the impression Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds are staying here. Once again, it’s left to the band’s security to capture the bird and release it outside. If it wasn’t so early in the morning, I could probably conjure some horrible metaphor for Blur here, so count yourselves lucky.

“For a band who wanted to move up to the next level, it meant the main task was finding some way to get written about in those papers,” resumes Dave. “So all the bands were constantly slagging each other off, and getting drunk and getting into fights. It just promoted the chaos of the whole thing. Every band had to have a political agenda, and there was this sixth form outlook on whether the bands meant it or not.”

“It did affect the music as well, though, in terms of the selling out thing,” adds Graham. “You couldn’t do a blues scale in a guitar solo, or even a guitar solo, really. There were a lot of rules. People would jump on you if you did anything like that.”

Rowntree sees further differences in today’s musical landscape.

“Bands spend all their time on social media now,” he observes. “That’s the gig when you’re not performing, you’ve got to be pushing yourself on TikTok and everything. In those days, bands had to be doing things that were press-worthy, to satisfy the voracious appetite of the music papers.”

Dave talks about his stint as a Radio X DJ, and says the quality of new music stopped him “falling into that middle aged rut, where you go on about how things were better in your day”. I take his point, but in the same way Tarantino wrote in Cinema Speculation about how much more exhilarating movie criticism was from the ‘60s to the ’80s, I still think music criticism was better in the ’90s.

“That was better then,” Dave concedes. “It’s terrible now. The temptation just to print the press release is overwhelming now, isn’t it? Because to do anything else means employing a journalist.”

“You just see the press release,” emphasises Graham. “Then you click on stuff and it’s another press release. There isn’t really such a thing as music journalists anymore, is there? It seems to be something that’s divvied out to whoever fancies doing it that week, and it’s not very intelligent. The thing about acts like Blur is that there’s such a lot of references – and quoting, nods to the past and mischief – that it’s completely lost on journalists, cos they’re either too young or too thick.”

ELVIS & THE POGUES

Another notable Irish Blur show came in summer 1996, when they wrapped up the Great Escape tour with an outdoor show at the RDS, in front of a teen crowd thrilled at having just completed their Junior and Leaving Certs. At the time, the band were experiencing a backlash in the UK, where Oasis were in the ascendant on the back of the all-conquering (What’s The Story) Morning Glory?, and about to play two sold-out nights in Knebworth.

But like Radiohead and Manic Street Preachers – their most serious rivals as the best UK rock act of the last 35 years – Blur have always drawn a lot of energy from going against the prevailing cultural grain. At the RDS, they debuted two new songs, the wailing punk thrash ‘Chinese Bombs’ and the grungy anthem ‘Song 2’ – eventually to become a staple at sports events the world over – as they embarked on another reinvention, which eventually came to fruition on their self-titled fifth album, released in early ’97.

“Other than a short period where a couple of records sounded a bit more similar than usual, all the records have sounded very different from one another,” says Rowntree. “That’s quite deliberate, we’ve never been particularly interested in doing the same thing twice.”

“On Blur we were thinking a bit more experimentally,” Coxon recalls. “I was listening a lot more to American stuff. On the next album, 13, we made a choice to go with William Orbit and then things got really free-form. We could take advantage of digital recording and the DAW situation had a lot to do with all of that.

“With the first few albums, we had to be really rehearsed and know our stuff – we couldn’t take a chorus and stick it on the end as an outro to see how it worked. But when Stephen Street brought in the Radar system on Blur, we could start to make loops and be a bit more experimental.”

The band would play the Point on both the Blur and 13 tours, while the itinerary for 2003’s Think Tank – completed without Coxon, who exited during the fraught recording – included a number of dates at Dublin’s Olympia. With the guitarist back onboard, Blur headlined Oxegen in Kildare during their wildly successful 2009 reunion tour, while The Magic Whip excursion found them topping the bill at Electric Picnic.

Sandwiched in between was a 2013 show at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham, the week of which also saw IMMA host a Blur exhibition, featuring artwork, photography and design from throughout their career. Of course, the four members always keep busy with on the extracurricular front too, with Albarn involved in numerous projects alongside the enormously popular Gorillaz; bassist Alex James making cheese and hosting the Big Feastival bash at his Oxfordshire spread; and Coxon composing soundtracks and playing in The Waeve alongside Elinor Rose Dougall.

Rowntree, remarkably, arguably outdoes them all. A qualified solicitor who has also served as a Labour councillor, during lockdown, he also found time to host his own music podcast on Spotify. A comment he made on one of those shows particularly caught my attention.

Reflecting on the radical reinvention Blur underwent between their baggy/shoegaze-influenced 1991 debut Leisure, and their 1993 sophomore effort, Modern Life Is Rubbish – a virtual anthology of late 20th century British rock and pop styles – the drummer said the band felt compelled to explore their English roots, in much the same way The Pogues dived into the Irish folk tradition.

Ironically, as an Irish person, my musical journey took me in entirely the opposite direction. The Pogues never made sense to me at all, whereas Blur – and their peers in Pulp and Suede – captured my experience very directly.

In the way they wrote about provincial towns, where you grew up inundated with pop culture but unable to escape, those groups spoke to my generation in a way the Irish folk tradition never could. We felt rootless and lacked identity, whereas The Pogues were about nothing but identity.

As Dave notes, Modern Life Is Rubbish grew out of a disastrous 1992 tour of America, where Blur found themselves severely out of kilter with the prevailing grunge zeitgeist.

“That experience in America definitely changed us as a band,” he remembers. “It was the first time any of us had been away from home for any considerable period of time. That changes you, there’s a lot of growing up involved in doing that. It gives you perspective on where you come from, so we definitely started to have those kinds of conversations.

“Damon talked a lot about it in interviews later, and explained how he was thinking, ‘What would music be like had Elvis not had the overwhelming influence that he’d had?’ It’s like asking, ‘What would music be like if The Beatles hadn’t had that overwhelming influence?’ But because we were in America, it was like, ‘Well, if you subtract Elvis, what’s left from popular music? What direction might it have taken?’

“That’s a really creative way to think about music, I think. Being away from home gave us the perspective to think about what we did and didn’t like about England. When you’re immersed in it, it’s harder to have those thoughts. Even though some aspects of that American tour were fucking horrific, in some ways that was the making of us, because we came back with a completely different mindset about pop music.”Dave offers a final thought on the band’s relationship with Ireland.

“Dublin’s always special for us because of Leo Finlay, who’s the journalist who discovered Blur,” he says. “We played just down the way at his wedding in the very early ’90s. He used to say similar things about The Pogues – it didn’t resonate with him at all, because he listened to all those bloody songs for years in the pubs growing up.

“It’s like, ‘I don’t want to hear them again when I go to a gig!’ But I was always entranced by The Pogues, because I hadn’t heard those songs before. It wasn’t clear to me which songs Shane had written and which were traditional folk songs. But that attitude of taking something and giving it – it’s a terrible thing to say – a punk ethos, I found really appealing. I thought it was just great.”

A look at some of the band’s most legendary Irish gigs

Feile, 1995

At what has become one of the most famous ever Irish festival line-ups, Blur headlined in Pairc Ui Chaoimh along with The Stone Roses and The Prodigy. Elsewhere, the bill boasted a Britpop who’s who (Elastica, The Boo Radleys, Menswear etc), as well as a remarkable trio of dance headliners in Massive Attack, The Chemical Brothers and Underworld. A large part of Blur’s set was broadcast on RTE television, with the peak arriving during a uproarious ‘Girls & Boys’, which found Damon Albarn bounding around the stage with a huge umbrella.

Point Theatre, 1995

The following November saw Blur hitting Dublin on the Great Escape tour. An instant sellout, the show was originally supposed to be followed by a second gig the following night, but a clash with the MTV Europe awards ruled it out. As well as the rapturously received hits, Blur also played the Great Escape fan favourite ‘Best Days’ for one of the only times ever.

RDS, 1996

Blur wrapped up the Great Escape era with this huge outdoor show, which was broadcast on radio all around Europe. Supported by Supergrass and Happy Mondays offshoot Black Grape, the band chose this show to debut the soon-to-be-iconic ‘Song 2’. Elsewhere, they were also joined by the late Terry Hall for a rendition of The Specials’ ‘Nite Klub’.

Oxegen, 2009

The band performed their first Irish gig in six years at the Oxegen festival in Punchestown. As with all shows on their reunion tour, it was a dazzling greatest hits set with songs from all stages of the quartet’s career. Before the customary finale of ‘The Universal’, Albarn dedicated the song to the late Irish showband legend Joe Dolan, who’d included the song on an album of cover versions.

Electric Picnic, 2015

Returning to the midlands, Blur hit Laois to perform a headlining set towards the end of the Magic Whip tour. The first half of the gig was broadcast on RTE television, with Albarn prompting an outburst of ‘Ole Ole’, after informing the crowd that a recent test had revealed him to be “11 percent Irish!”

• The Ballad Of Darren is out now.

RELATED

- Music

- 27 Apr 25

10 years ago today: Blur returned with The Magic Whip

- Music

- 30 Sep 24

Oasis announce North American leg of reunion tour

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 09 Sep 24

West End play to retell story of Blur vs Oasis battle

- Music

- 26 Jul 24

Blur release trailer for Blur: Live At Wembley Stadium film

- Music

- 26 Jul 24

Album Review: Blur, Live at Wembley Stadium

- Film And TV

- 07 May 24