- Music

- 05 Oct 21

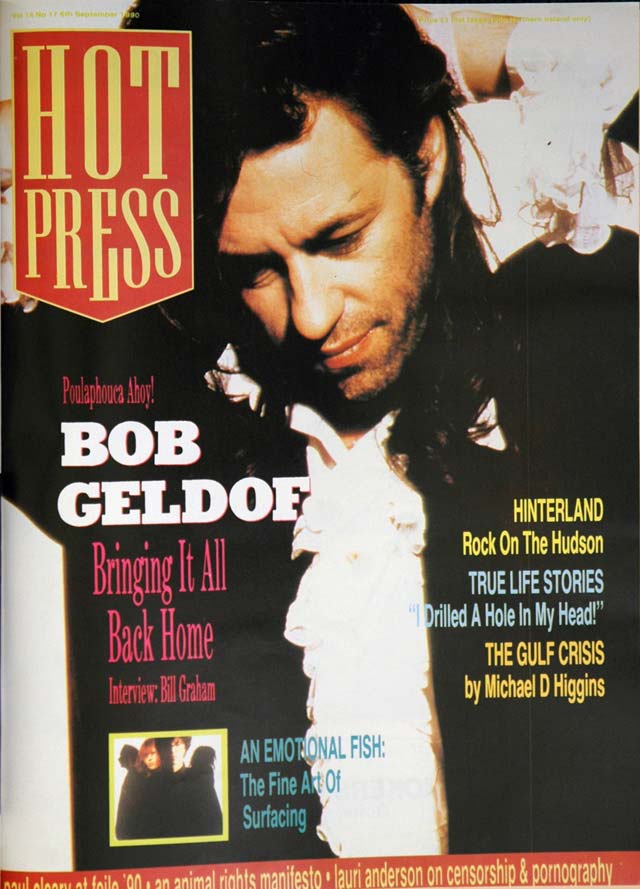

Bob Geldof at 70: Revisiting a Classic Interview

Happy 70th Birthday, Bob Geldof! To celebrate, we're revisiting the Irish icon's classic interview with the late, great Bill Graham – originally published in Hot Press in 1990.

With his upcoming concert in Poulaphouca marking his solo Irish debut, it's been all too easy in the recent past to overlook Bob Geldof's standing as a musical and lyrical artist. The lines connecting the youthful Dun Laoghaire blues and Dylan aficionado with the creator of The Vegetarians Of Love are rarely traced in media-bytes that prefer to concentrate on Modest Bob, Live Aid Bob and Saint Bob. Here, Bill Graham, who knew the schoolboy, takes musician Bob on a freewheeling trip from then to now.

In the Princess Grace suite of the Shelbourne Hotel, a lanky man in black plucks at a guitar and explains how it all began in secondary school over twenty years ago when he borrowed a friend's acoustic.

"The first song I played on Justin Fawsitt's guitar, I was trying to work out chords and he wouldn't let me change the strings around because I was left-handed, so I did this (strums) and then I did that (strums) and it was a Who song."

"So," continues Bob Geldof, for of course it is he, "there's not much difference between that person, someone who wrote 'Looking After No. 1' a year before Tom Wolfe's 'The Me Decade', someone who wrote 'Do They Know It's Christmas' and someone who wrote 'The Great Song Of Indifference'."

The point of this trawl through his past is that Bob Geldof would like it known that he now wishes to be seen as a working musician. Not Boomtown Bob, Modest Bob, Sir Bob, Saint Bob or any other of the host of personae the media have projected on him. Just Bob Geldof, a middling successful Mercury recording artist.

I'm at one with his wish, I'm not in his hotel suite to adjudicate on world politics or sustain the discontinuities between the original punk/pop iconoclast, the later rock philanthropist and the solo artist before me. Instead I want to trace the continuities.

I have one advantage. I know who Justin Fawsitt is because I was in that same Blackrock school year. Nine years before the mast when this B.G. followed that B.G. in the school roll. Not that we were ever intimate. While Geldof disrupted - and his autobiography Is That It? is an entirely accurate account of those years - this boarder hid his own growing pains, conformed and survived, till I passed my Leaving Certificate and could taste the freedom of University.

So I conformed to the code of a school which made an absurd and unhealthy fetish out of sport and especially rugby - unlike Geldof who was always knees and elbows, the most manically, physically uncoordinated adolescent ever. In the compulsory schoolyard seven-a-side soccer tournaments which even that confirmed sports-hater couldn't always escape, Bob Geldof was always the last of the last to be picked, to be then immediately exiled to the opponents' penalty area where he could cause the least damage to his own team.

But I was on the fringes of the musical circle that included him since like so many school sports victims, Geldof found his refuge in music. But Geldof and his friends weren't proto-hippies. Instead back in '67, they shared a common allegiance to the blues and as raw and authentic as they could find. Blue Horizon was the hip label and albums by exotic names like the piano-player Roosevelt Sykes got passed around. Indeed the first album I ever bought, by the country blues sage, Mississippi John Hurt, was one I'd first heard from the Geldof group.

So when Bob Geldof discarded pop and changed his style for The Vegetarians Of Love, it wasn't some late Pauline conversion. Unlike U2, Bob Geldof doesn't come from a generation that had scorned blues and other roots music. So musically, The Vegetarians Of Love really is an album that completes a circle.

Again let's trace continuities, especially since we who can still take our media weather from London, can perceive Bob Geldof's solo career as an untidy epilogue to Live Aid. As Geldof himself insists in almost the first breath of our interview, his debut solo album, Deep In The Heart Of Nowhere, sold over a million copies throughout Europe - it's primarily in the British and Irish music media that Bob Geldof and The Boomtown Rats remain an embarrassment to punk archivists. In 1990, you can commemorate original inspirations like Iggy Pop, survivors like Debbie Harry and fashionable Manchester influences like The Buzzcocks, but the Rats weren't a Stones, Who or Kinks, more their era's Manfred Mann, capably adapting to the tides of fashion who nonetheless maintained a sturdy independence in the lyrics and attitude. But London style arbiters condemned the Rats as unhip and Bob Geldof is still trapped by that verdict.

He immediately concedes the point: "We were always desperately uncool so I find it hard now to be even vaguely credible with this album, which completely bewilders me. I've never been cool, I've never been credible, I ve never sought to create an aura of mystery or an enigma."

Simultaneously with The Vegetarians Of Love, unbeknownst to Bob, a live video of the Rats was released. Accepting the weight of received wisdom, its NME reviewer, Stephen Dalton damned the Rats though in truth, he later had the grace to partially approve them. But "the Showaddywaddy of punk" isn t that the sort of one-liner that continually debars Bob Geldof from artistic credibility?

"Of course, I'm sure that's how people perceive me," he responds. "But I don't give a shit, ever - that period, before or now. But the plain fact of the fucking matter is, as I stated then, we were not punks. I had nothing in common with that attitude but what irritated them about me was that I wouldn't play that game. I thought the Stones were great and Dylan was brilliant. If I had half or even a quarter of the voice of Van Morrison, I'd be a lucky man."

As ever, the combative advocate in Geldof warms to his statement of defence. "This profoundly irritated them because it was Stalinist in that you had to revise history for the new boys. I also blew the whistle, in my opinion, on The Clash. I thought they were The Bay City Rollers. These people today forget I was there and The Clash were tailored out in clothes that were meant to be rock chic and they were given attitudes that they had to mouth and they were second-hand. And the only one, as I said then, who I believed to be genuine was Johnny Rotten, who was beyond Malcolm McLaren's machinations in the end. And it doesn't mean I don't like those people now. In actual fact, I do. But I didn't at the time and they didn't like us.

"I'm not harping on this because it's not fair, but you must remember we were Irish," he points out. "We were outsiders. If we'd come from Cornwall, it would probably have been the same. But we were a bunch of guys living in one house in Chessington, (near the zoo in Surrey) and you can check with BP Fallon on this, the reality was that we were gathered together for safety. We were babes in arms, not intellectually, but in this field. And we were uncool but we were getting massive audiences."

"And," he continues, hitting his punchlines, "this was not quite what was meant to happen. I was saying things that were not part of the NME gestalt which was dictating that gestalt." He remembers one incident, a London party for The Ramones with whom the Rats had just played: "Gen X, the Pistols, The Clash, The Jam, everyone was there and they wouldn't let us in."

That rebuff revived earlier London memories. After Blackrock, he'd worked one summer in a Peterboro pea-canning factory and he says: "I came down to London, looking for digs and I was seeing signs "No Dogs, No Irish" and no matter what way you cut it, that's what was going on. Not because we were Irish but because we were beyond the Pale and didn't join in. Not (adopts the era's street-cred Cockney punk accent) facking Lahndan scene."

Why so little in common?

"Well," he answers, "it boiled down to the fact that I did not believe that Top Of The Pops was the main problem with the world and they did. Of course, they d all say they didn't want to be on Top Of The Pops when I knew for a fact they were all trying desperately to get on and as soon as the Pistols got a chance to be on, they were on. Then everybody turned around and said it was a great victory."

Thus Bob Geldof would style himself as the pragmatist who scorned the posturing in punk. Reality Man with the Shit Detector. In fact, the truth is more complex than can be gleaned from his comments on one side of a C90, since the Rats couldn't but partake of punk's energies and opportunities. Still as Geldof rightly claims, they were the first to win the chart sweepstakes.

"Forgive me if this sounds immodest, it's not meant to be, but after a year and a half, we were dictating what pop music was, we were setting the agenda for it. In pop music terms, we were where it was at. Other bands would look and say, that's the standard. Our production, our sound, the live stuff, the videos, it was all working.

"But," he concludes, "after that, like I said in the book, what happens to a pop band? What are you meant to do after your platinum albums?"

For one, everyone who's been waiting for you to stumble gets their revenge. All your own more sarcastic asides get repaid in spades. Once synth bands, like the Human League and the original New Romantic groups like Spandau Ballet and Duran Duran emerged, the Boomtown Rats were summarily ejected from the charts.

Actually, their earlier inability to crack America may have been the killing blow. The story is oft told - of how the subject-matter of 'I Don 't Like Mondays', its story that of a girl who'd taken her revenge on her school-mates by shooting them, had confounded the prissy sensitivities of American radio, and how, earlier, Geldof and manager Fachtna O Kelly had foolhardily wound up CBS promotion staff and radio programmers at a record company convention.

Whatever, an entree to America might conceivably have sent the Rats back to their original R'n'B influences and established a more durable base for their future. Geldof himself might have reverted to Springsteen and Dylan as his models. Instead he could sometimes seem an awkward cut-price Irish Bowie, flirting with the new dance market. And that was his and the Rats' downfall.

He defends Mondo Bongo, their fourth album but, to my mind, it's the Rats' worst and certainly most disjointed. They switched producers to work with Tony Visconti, Thin Lizzy and Bowie's studio majordomo. The guitars of Gerry Cott and Garry Roberts went AWOL and Visconti's treatment of Geldof's and the group's harmony vocals lacked the rigour of their earlier treatments of their initial producer, Mutt Lange.

It wasn't that the songs themselves were crap. Rather Mondo Bongo sounds the work of a band and producer without the common judgement, discipline and refreshed creative energy to nail their ideas down. Geldof's reggae diatribe against Ireland, 'Banana Republic', charted in the slipstream of their earlier hits but the rest was chart and radio silence.

Yet my low opinion of Mondo Bongo is irrelevant. Even if I thought it a masterpiece, the record was out of time. No crooner, Geldof's own vocals got by in the punk era while noisy, intrusive guitars reigned, but hears alongside the smoother New Romantic choir-boys like Simon Le Bon, Tony Hadley and Phil Oakley, he grated.

So I probe, perhaps the Rats would never have been successful if they had all been five years younger and started around 1980? Perhaps even Bob Geldof himself might have been disinterested and instead sought his fortune in some realm of the communications business?

"There's too many factors at work," he rightly responds to my hypothetical-with-hindsight question. "One, R n B would have to have been acceptable again. In 1982 that was definitely not the case. Like, there had been for us, Eddie And The Hot Rods and Doctor Feelgood, and the Feelgoods I adored. We actually started before them but when I heard Fachtna playing me their records, I actually said what is the point of doing this? "

He briefly enthuses about the Feelgoods before returning to the theme: "So yes, you could argue that maybe I might have done with the others in 1982 but it wouldn't have been successful. But maybe if I hadn't gone to the pub, Fitzgerald's in Sandycove, the night Johnny Fingers and Gary Roberts were there, I wouldn't have done it either. So, it's a useless speculation but the conditions may not have been as ripe for the Rats to have been successful in any other period but that. Certainly Ireland wasn't so far removed from general attitudes and feelings that in 1975, a lot of people weren't fed up with the local band scene with its endless rehashings of the Doobie Brothers."

Bob Geldof, October 1990.

Bob Geldof, October 1990.As for the Rats' slide, Bob Geldof's own interpretation is that Mondo Bongo was a relatively successful exercise in shedding their previous pop format and finding a new rhythmic base that wasn't RnB. But then prior to their next album,V Deep, he says, "I did The Wall and then we all fucked off to India and basically I think the time had changed.

Hitless but hardly listless and again produced by Tony Visconti, V Deep was a much tighter affair than its predecessor. Geldof says of it: "I remember Never In A Million Years , which is a track I like very much and which had that big, huge production. I still like that sort of maelstrom of sound, but it wasn't a hit. So at that stage, we were no longer in the swim. We weren't the Human League and pop music is unforgiving and I understood that. It wasn't that I was bitter at the time."

So what was your own creative mood then?

"That was the worst, V Deep, because financially, we were in desperate straits because it did fuck all. We had to regroup seriously. So Fachtna left around that time and we had no money and I remember rehearsing up in Acton in this fucking miserable, cold room and nobody came around to see what we were doing. And we rented Denis Bovell's studio in Southwark and it kept going slow so the next day, you'd come in, do overdubs and it would slow down and you'd have to scrap the tracks.

"Yet," he insists, "we made some great records in that period and I always sort of believed that if you did a good song, you'd get in the English charts. And, we made this album, In The Long Grass, for about 30,000 and without question for me, it's the absolute best of the Rats records.

But then Geldof saw Michael Buerk's BBC report on the Ethiopian famine and Band Aid was born. So he concludes: "We had to literally kill that record and sit on it really because it would have been seen to be exploitative had we not." So also were the Boomtown Rats finally exterminated.

Really, there's no sense in repeating questions and answers about Live Aid . What more intrigues me is why Bob Geldof alone responded to Michael Buerk's newscast from Korea. But maybe he actually partially anticipated the script before Band Aid from The Fine Art Of Surfacing: They saw me there in the square when I was shooting my mouth off/About saving some fish/Now that could be construed as some radical's views or liberal's wish .

The only thing remotely Green about punk was snot and gobbing, yet at the peak of the Rats fame, Geldof again wandered off the plot to speak at a Save The Whale rally in Trafalgar Square, potentially exposing himself to punk jeers and accusations of backsliding pro-hippie tendencies. Given that one major effect of Live Aid was its stimulus of the Greening of rock, that early gesture again shows a continuity in Bob Geldof's values.

Even his later Rats' lyrics show his lack of rock parochialism with a raft of picaresque references to Third World countries and situations. You can even speculate about the itchy feet of the Geldofs, who were, after all, a Belgian family removed to Ireland with his elder sister Lynn, the Irish Times correspondent in Cuba.

At 16, he was no saviour, working out his bitterness, baiting the French teachers, most often Holy Ghost priests invalided off the missions for physical or psychological reasons. Or did the fact that the Holy Ghost Fathers were a missionary order unconsciously open up some circuit in him?

Probably not since he almost gleefully relishes reminding me of his precocious political radicalism and my own typical teenage conservatism. "Me and Mick Foley (not of the Irish Times) started up young CND in south Dublin and then the two of us were specifically involved in the Anti-Apartheid Movement at 14 and then I got browned off with gesture policies so at 15, given my home circumstances which was that there wasn't anyone at home, so I didn't have to do any homework, I just bunked off at night and worked with the Simon Community.

" And," he continues smiling, "you were in the debating society and you actually voted that the Americans stay in Vietnam and I was the sole dissenting voice," though not by the 283-1 minority, misquoted or misprinted in a recent Face feature. It was 28-1, more likely.

Swiftly changing tack, I ask about family and other school influences but he makes a more general response. "I really think the Irish are the European Jews. They've got a greater diaspora, almost. Without question, their contribution to 20th century intellectual life is enormous. I mean the idea that the Irish leave is embodied in us. The other thing was that I was raised Catholic and you never rid yourself of the voodoo. And the Irish look out, they re not insular, they must do."

He's still casting around for explanations: "I've always been bothered by other people. Nearly all my songs like 'Rat Trap' and 'Joey' are about other people. It's no big deal but in the end, talking about 1977, I would question who was the one who kept remaining part of that whole thing, who kept questioning, shouting and took it to its logical conclusion and actually went right up to the top."

"But," he says bashfully, "I can't answer that question. You and people outside of myself have to answer that and say he was influenced by that whole Black Babies thing or not. That isn't what angered me. What angered me was the intellectual absurdity and moral evil of it."

So Bob Geldof claims it's he who most kept faith with the spirit of '76. That's exactly the sort of unqualified assertion that once had the media descending on his carcass to rend his reputation. Indeed, it's wide open to objection insofar as both Punk and New Wave appealed to the non-joiners who would never be conscripted into the Boy Scouts and Girl Guides.

Indie fans will also angrily argue that Live Aid betrayed punk codes by re-establishing the stadium hierarchy. Yet as the Rats' own decline proves, the New Romantics and their contemporaries had already quashed the punk revolt and reintegrated British music into that self-same hierarchy long before Live Aid.

And awkwardly knees and elbows as ever, Bob Geldof does have a point. You can argue the toss from a variety of aesthetic and political positions but Geldof can claim that Live Aid temporarily re-empowered popular music by dragging it out of the cultists ghetto and re-connecting it to a real cause.

Meanwhile, Geldof's own iconoclasms remain unquenchable. For instance, he'll dispute the long, grim slide theory of popular culture. And needle those who automatically criticise the corporate Eighties in comparison to the previous decades.

"Really, 'Looking After No. 1' was a calling card. People characterise the Eighties as being this greedy, yuppie Wall Street thing. But for me, it was the opposite, it was characterised by overwhelming kindness and generosity. Also I think a lot of bollocks is talked about the Seventies. In the Eighties, a bunch of young kids who talked (goes Cockney again) loike that got to work on the stock exchange and they were 18. Now since when does an 18-year-old not want a big car or to have money for clothes or to spend it irrationally?"

"That's what yuppies are . . . and yes, I understand that the value they put everything on was money. But, nonetheless, there's an awful lot of bollocks about the Seventies. The late Seventies were immensely selfish and greedy and you had Britain brought to its knees by a bunch of cunts who wouldn't even bury dead people. Like I lived there when the streets were piled up with litter for a half-per-cent extra pay. That's greed. It isn't revolution no matter what way you cut it."

"Now I was in Ireland when I wrote 'Looking After No. 1' and there was a definite atmosphere of selfishness, and I disliked the whole hippie thing of Tune In, Drop Out because that inevitably led to an intense selfishness in the Seventies. And a year after I wrote the song, Tom Wolfe wrote The Me Decade , the most brilliant polemic of its generation, and ' Looking After No. 1' was the same thing."

With Geldof, themes whistle past like freight-cars and you can't really profitably interrupt when you disagree with his overstatements. Yet it is all, ultimately, bracing 'specially since all rock theorising, including the new hedonism, has to be veiled in falsely radical guise.

His unorthodoxy means that Bob Geldof will also finger pop's sublime indifference to Eastern Europe. "Pop music," he'll insist, "if it is to survive as an entity, must be the expression of its time and what I hear now is indifference. As I said ' I Can Dance Away' but 1989 was one of the most important years of the 20th century, if not the modern age, when the world quite literally changed. And with that comes all the tension and potential dangers that are inherent in the optimism. And I've been around now and there' s just this level of apathy, with the obvious exception of Germany.

"My point," he concludes rather pessimistically, "is that there doesn't have to be a track about China but the music should be of its time. But maybe it actually is. Maybe the songs are so fucking bland that that is the time."

Once, Geldof used to be taunted for such generalisations. But now with his protective celebrity, his critics prefer to immunise and quarantine him. Yet surely it s wrong-headed to disclaim the expert witness of the man who created Live Aid on the meaning of Pop. Indeed it s almost as if Bob Geldof has become some mythical heraldic beast in the pop zoo, to be admired from afar by the visitors but never to be freed and let loose on their pockets.

He's said it before and he says it now again: "Personally, Live Aid was an emotional, financial and professional disaster . . . though now I've had the time to resume my financial, professional and emotional career, things have stabilised, thank fuck!"

Certainly The Vegetarians Of Love is a less stressed and more upbeat album than its predecessor, Deep In The Heart Of Nowhere, Bob Geldof sounds much more comfortable within himself.

"It's obviously radically different," he reflects, "because it was made under radically different circumstances. Deep In The Heart Of Nowhere I like very much when I listen to it, mainly because it's unerringly accurate about what I felt like at that period- which was deep in the heart of nowhere."

"But, subsequent to that, it did relatively well for me and I toured in Europe with this band and got great reviews which restored my confidence. And then I got browned off as normal and went off and did other things. It seems necessary for me. I seem to take two years per album and I seem to require that amount of time to either have different experiences or to view the same things differently."

"With this one, there's several factors which give the atmosphere of being comfortable with myself," he continues, "one is my renewed sense of confidence. Possibly the second is that, being without the politics of being in a band, it's far more personal since I could completely dictate the course of events and I wanted spontaneity which is the key thing to it."

"Like there are times when I m half not-singing and there s also this crappy guitar playing which is the way I would write songs and play it to the Rats. This I think you can take as the first solo album whereas Deep In The Heart Of Nowhere was obviously an interregnum.

He says he told the players he wanted something with the spontaneity of cajun . Before recording The Vegetarians of Love, he'd gone to Lafayette deep in the heart of Louisiana and got entranced by cajun music. "As you know, I always liked the blues and here in Lafayette was this great drinking, driving music but so passionate people were singing about their lives and it was not stupid. "

Again Bob Geldof traces the continuities: "I felt very like in '75 when you put on the radio and you heard the Bay City Rollers and disco . . . Because House, Hip-Hop and Kylie and Jason are all well and good and I like dancing to House music but after half-an-hour, I m going yeah, well, maybe I ll go and have a drink . . . It doesn't satisfy me in any way, spiritually or intellectually. So my ear wanted to hear this other music."

"In retrospect, I guess 'This Is The World Calling' is a Live Aid song because my mind was crammed with imagery of despair, personal despair and the confusion of wondering what the fuck would I do next. So it was a desperate acknowledgement and a plan for beauty. Like there was one verse which goes, I'm on a train, now, I'm moving through the yellow fields of rape, there' s so much beauty, I wish that I believed enough to pray . Well I don't and I envy those who believe enough to pray. You could blame so much on external forces if you did believe enough to pray."

But Live Aid surely offered him transforming experiences not granted other songwriters. Earlier, his ironies and sarcasms could carry a taint of coat-trailing attitudinising, which is no longer the case. I throw him an archival quote from the Village Voice's Robert Chrisgau, who in a thumbnail review of The Fine Art Of Surfacing, wrote "Geldof has a journalist's gift. He makes terrific topical songs if only he believed in something." Is there a difference between Bob Geldof then and now?

He disagrees. I don't get that. Then he laughs: "It's fucking awful. I'm not going to make such a fucking rash declaration at this point but I do believe that man is good. I'm optimistic about the world. I do believe that 95% of people are good. I said this to Charles Shaar Murray the other day - and he said the other 5% are journalists, boom boom!"

Levity aside, he continues his declaration of faith: "My value system is largely based on that I wished for God. I wished I believed in God so that when I opened my eyes, I could just say so be it, that what god wants. But I don't believe that. I believe that man has created most of his own problems so therefore, it s soluble by man. But having said that, I m, not a cynic. I think cynicism is unhealthy, while scepticism is necessary. Until the day I die, I'll be saying why or why not? I will not accept received wisdom, be it from the establishment or the counter-establishment."

He returns to The Vegetarians Of Love: "On this album, I don't think I'm reiterating a value system. I don't think it's any more personal than the others but people seem to think so. And that's mainly because of the delivery of the voice or because it's so spare."

But 'Thinking Voyager 2 Type Things' has a special positivism?

"I'm glad you picked up on that," he responds, "because somebody gave that as an example of: do I ever stop being a miserable fuck? And I thought, wait a moment, that's the opposite of what I was saying. Voyager 2 is this little piece of steel with a camera on it that man threw out like a skipping stone across the water. For me it's an object of the ingenuity of this animal and the curiosity of this species. So I thought here's this animal who can make this wonderful thing, just skip it around the planets, close up and take pictures and beam them back to us from billions of miles away.

"And in this little blueball, for all we know, all our experience is contained... And then I thought, it ' probably loaded with microbes and it will crash into some asteroid and then life will begin again. And that point of impact is the line: this is the moment when we come alive. And of course, I was wearing my Brendan Behan teeshirt."

Of course, the new album also removes Bob Geldof from Pop and with his own self-styled "crappy" guitars, takes him back to New York's Greenwich Village folk scene. But yet again let's trace the continuities. After all, didn't the Boomtown Rats' title come from Woody Guthrie?

That comparison hits paydirt. For Geldof, the final track 'The End Of The World' is patterned on Woody Guthrie in the phrasing. Then he gets exasperated by misinterpretations of that closing comic turn.

"That's a funny song yet it's so weird. Does this happen to other people in that they like to examine the runes and take me so seriously? It's self-evident that's a highly ironic song but I get stuff like - "Bob, are you comparing yourself with the Buddha?" I've got letters from people asking me, "who do you think you are?" and they haven't even heard the fucking thing."

But in his typical switchback way, he finally homes in on my original question as to whether he has or had two musical characters, pop Bob, and roots Bob. He sees no conflict: "Back at school, I could go out and buy my twelve and sixpenny Lightin Hopkins album on Music For Pleasure and the next day get 'Substitute' by The Who and I could see a direct correlation. But now I don't hear that passion. It's not that I'm trying to relive my youth, but what I hear now is..."

He says it again, "...indifference."

So is Bob Geldof out of time and out of place? Not according to one beguiling anecdote. After his recent London showcase date at the Town And Country Club, a 19-year-old guy approached him to sign his guitar. Then he recounts with relish: "I asked this guy was he in a band and what was his name? Yeah, it s called Twenty Four Night. And I said that's a good name. Yeah, he said, it's from one of your songs. And I was (self-mocking) intensely flattered. And I said what do you do? And he said we do all Rats songs. And I said, are you sure that's a wise career move?

"So I thought that was weird. And the week before, I was with the lead singer in James, Tim Booth, and he said to me, I interviewed you twelve years ago. And I said, no doubt it was a brilliant interview. And he said it was, you gave more time than the NME. And I said that's fair enough, I'm consistent at least.

"And then I said did you go to the gig? And he said, yes, it was brilliant. So I said, no doubt a seminal influence. And he said, you're right. Two days later I began writing songs."

RELATED

RELATED

- Music

- 04 Nov 25

On this day in 1991: My Bloody Valentine released Loveless

- Music

- 27 Oct 25

On this day in 2006: Amy Winehouse released Back To Black

- Music

- 21 Oct 25