- Opinion

- 24 Nov 20

"Influencing others with his words was what he wanted, and that is what he got." Casey Rae argues for William Burroughs as "a clandestine agent in the development of rock n' roll."

He didn’t look very rock n’ roll. Perhaps the regulation shirt and tie, sometimes augmented by a trilby, were worn in order to infiltrate and blend in with the world around him, all the better to battle control, to fight the men – and the aliens – who would work the soft machine. Look, there he is in the background on the Sgt Pepper album cover, sandwiched between Marilyn Monroe and Sri Mahavatara Babaji, hiding in plain sight, fighting the power.

Casey Rae’s rather excellent book isn’t a straight biography of William Burroughs, one of the holy trinity of the beat movement, and the man Norman Mailer – who rarely had a good word to say about anyone but himself – called “perhaps the most talented writer in America,” as much as it is a Venn diagram that highlights Burroughs intersections with the world of rock n’ roll, and the bookish oddballs that created some of its most vital output.

Despite the eternal outsider status, Burroughs was born into money. His grandfather invented an adding machine and his parents sold up just before the great depression hit, meaning that for years, as Burroughs roamed the earth in search of experience, he did so with a monthly stipend of $200 in his arse pocket. That’s not to knock what he achieved, it just made buying the ticket – that exploded – a bit easier.

It’s not a straight biography, but Rae does fill us in on the blanks before rock n’ roll gets going. There were early forays with drugs and booze at Los Alamos Ranch School in New Mexico, where his sexual preferences were already in place. Rae puts in like this, “he was somehow convinced he was unlovable, which drove him to be attracted to men who were not in a position to reciprocate. Either they were straight, or mostly straight, or not interested for other reasons.”

After his parents sent him to Europe for his graduation, he enrolled in a Vienna medical school and then married Ilse Klapper so she could get a green card. Burroughs' longings were elsewhere, illustrated by his Van Gogh-like removal of the tip of his finger because of a boyfriend called Jack Anderson. He tried for the navy in 1939, but physical shortcomings got in the way. More intriguing is the near miss when he interviewed for the OSS – the precursor to the CIA – but was nixed by a former Harvard housemaster. The time travelling, shape shifting secret agent Inspector Lee in The Soft Machine would be as close as he’d get.

Advertisement

The Beat(en) Generation

In the New York of the early 1940s, he meets Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, the other two members of The Beat Generation’s big three, he starts using morphine, and he begins his relationship with Joan Vollmer, who is as fond of amphetamine as he is of opiates. She lives as his common law wife as he moves back first to St. Louis where his parents were, and then to Texas, where their son William junior is born in 1947. Burroughs flees – possibly from the law – to Mexico. Vollmer and the children – she had a daughter from her previous marriage – follow. This proves disastrous as Burroughs chases men while Vollmer takes to the bottle.

At a party in the Bounty Bar in Mexico City, a pissed up Burroughs announces that it’s time for their 'William Tell act'. Vollmer puts a shot glass on her head, and Burroughs puts a bullet in her skull. He would change his story later, claiming he dropped the gun and it accidentally went off. Vollmer’s daughter was shipped to her grandparents, while William Jr goes to live with Burroughs' parents. Bribes are paid, bail is secured, Burroughs skips town.

Vollmer’s death was seen by Burroughs as the event which prompted him towards being a writer, although his first novel, Junkie, had, for the most part, been written before the incident, and the follow-up, Queer, which wouldn’t see publication until 1985, finds the narrator in pursuit of another man, rather than relating anything explanatory. Despite the subject matter, both of these novels betray a certain conventionality when compared to what came next. That being said, Lou Reed, as Rae points out, used Junkie like a road map. “The Velvet Underground’s ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’ captures the anxiety of the addict and is a direct descendant of Junkie. Even more obvious is ‘Heroin’, a micro-symphony of self destruction.” Rae quotes Reed on Burroughs when he said he was, “the person who broke the door down… he alone had the energy to explore the interior psyche without a filter.”

It’s hard to argue with Rae’s assertion that the artist Brion Gysin was “probably as important to Burroughs’ work as Burroughs himself.” Burroughs attributed the cut-up technique to his friend, who he watched create art when they both stayed in Paris’ ‘Beat Hotel’ on Rue Git-le-Coeur. Gysin apparently stumbled across the technique by accident in 1958 when he was trimming a canvas and cut up some newspapers by mistake. When he rearranged these cuttings, he saw something that he thought would suit the writings of his friend.

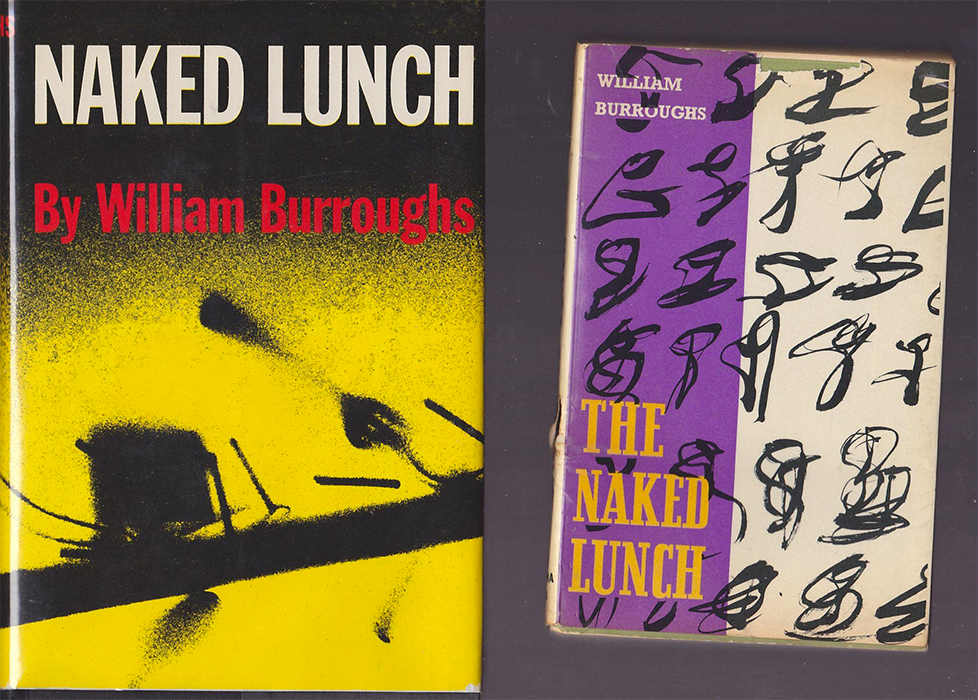

Burroughs was in Paris after leaving Tangier, and his most famous work, Naked Lunch, would comprise of vignettes composed in the Moroccan city, and then pieced together – and rent apart – in the French capital. An influence on everyone from Steely Dan to Bomb The Bass, it is, if you haven’t read it, just as out there as its reputation suggests. William Lee, Dr. Benway, Hassan’s orgy, the black meat, Interzone; Rae sums up the unsumupable, pointing out that, “as exploratory as rock music would get in the coming decades, it still pales in comparison to the headfuck that is Naked Lunch.” Carrying a paperback copy of it around helped me get my leg over - once - as a young undergraduate in the early nineties, such is its enduring talismanic power. It's possible I even read some of it at the time.

Advertisement

Thru' These Architects Eyes

The great and the good - and the not so good - intersect with Burroughs at various points from here on out. Bob Dylan was given a copy of Naked Lunch in 1959 and although they would meet only once, Burroughs’ techniques were certainly an influence when he jumped from folky troubadour to hippest man in the world sometime in 1965 and birthed his electric trilogy – Burroughs is there on ‘Tombstone Blues’, as Iggy Pop pointed out - and his influence permeates Bob's unintelligible ‘novel’ – the real mid-sixties Dylan accident – Tarantula.

Burroughs would also brush up against the decade's other rock n' roll godheads. He followed electronics wiz and object of his affection Ian Sommerville from the Beat Hotel to London and ended up in Ringo Starr’s old flat, recording his spoken word/cut-up/experiments on machinery left behind by Paul McCartney. There, he would witness Macca putting ‘Eleanor Rigby’ together, inspiring one of the great understatements of all time when he would later say of the Beatle genius, “I could see he knew what he was doing.” McCartney spoke at length with Burroughs about cut-ups and they even made some tapes together, although none of them survive. You can listen to ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ for yourself, to see if McCartney was paying attention.

Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka is an oddity in The Rolling Stones catalogue but it was a favourite of Burroughs for the rest of his life, who described it as "the primordial sounds of a 4,000 year-old rock n’ roll band” and would favourably compare Led Zeppelin to that sound when he reviewed Page and Co for Crawdaddy in the seventies. Jones and the other Stones had been drawn to Morocco in part by Burroughs’ adventures, and Gysin had been a fan of the Master Musicians since the fifties. Perhaps less well known is Jagger’s acknowledged use of the cut-up technique on Exile On Main St’s ‘Casino Boogie’ and the influence of Burroughs’ Cities Of The Red Night on ‘Undercover Of The Night’. Jagger even turned up as a character in the latter parts of Burroughs’ Red Night trilogy.

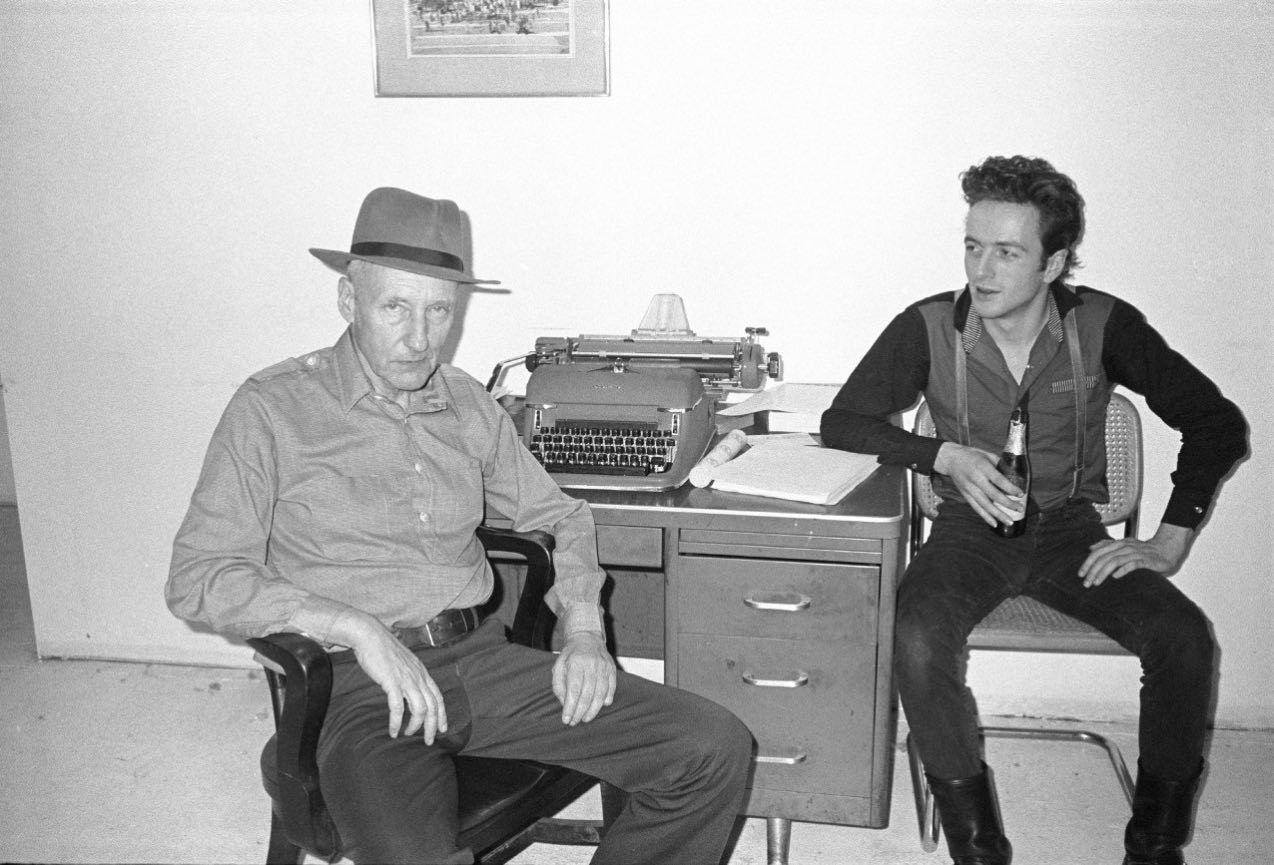

Both Dylan and Lou Reed are celebrated on Bowie’s Hunky Dory, so it’s possible Mr Jones found out what was happening from those sources. What is certainly true is that Burroughs’ techniques were a huge influence on the man, who used cut-ups on everything from Diamond Dogs to Blackstar, even going so far as to commission a computer programme to take the donkeywork out of it for 1. Outside, an album that reunited him with Brian Eno in 1995, another man who surely had some Burroughs in his library. Bowie and Burroughs met to interview each other for Rolling Stone in 1974, for they had a lot in common, not least their interest in both the occult and narcotics, a pass time that nearly sent Bowie sailing for the western lands, decades before his appointed time of departure.

Advertisement

Call Mr Lee

Burroughs’ was holed up in his bunker in New York in the second half of the seventies, which put him in close proximity to the likes of Richard Hell and Patti Smith. The Johnny in Smith’s ’Land’ is the same one in Burroughs’ The Wild Boys, although not Johnny Yen from The Ticket That Exploded, who would turn up a short while later in Iggy Pop’s ‘Lust For Life’. Smith would become a life-long friend and would visit and sing to Burroughs in Kansas near the end of his days.

There are many more stories, of course, involving the great – Tom Waits collaborated with Burroughs on The Black Rider – and the not-so-great – Duran Duran’s 'Wild Boys’ song and fairly preposterous video were supposed to serve as a trailer for a proposed full-length movie based on the novel of the same name. Even when Burroughs had settled in the red house in Kansas, because it was cheap and it was quiet, he would still be visited by Sonic Youth, Michael Stipe, and Kurt Cobain (Burroughs and Cobain collaborated on 'The "Priest" They Called Him', released shortly before Cobain's death). His final filmed appearance would be as part of U2’s video for ‘Last Night On Earth’ in 1997.

A passing knowledge of Burroughs’ work, his obsessions, and his philosophy – and all are expertly explained by Rae – make the connections sought and made by these musicians easy to understand, for Burroughs' subversive life-long battle against the forces of control, using his art as his weapon, is the very stuff that rock n’ roll claims to be made of. Burroughs kicked against the pricks with both the written word and his influential audio recordings – just like the ones in Ringo’s flat. “When you cut into the present,” he said “the future leaks out.” It doesn’t even have to be true – although it quite possibly is – because it sounds cool, which is always a good half of the battle. Taken to another level, Burroughs correctly predicted the world we live in today, “I advance the idea that in the electronic revolution, a virus is a very small unit of word and image.” If you can’t recognise our meme and slogan driven reality in that, then you too might be under the forces of control. Fight the power.

William S. Burroughs And The Cult Of Rock N' Roll is published by White Rabbit Books.