- Music

- 12 Nov 20

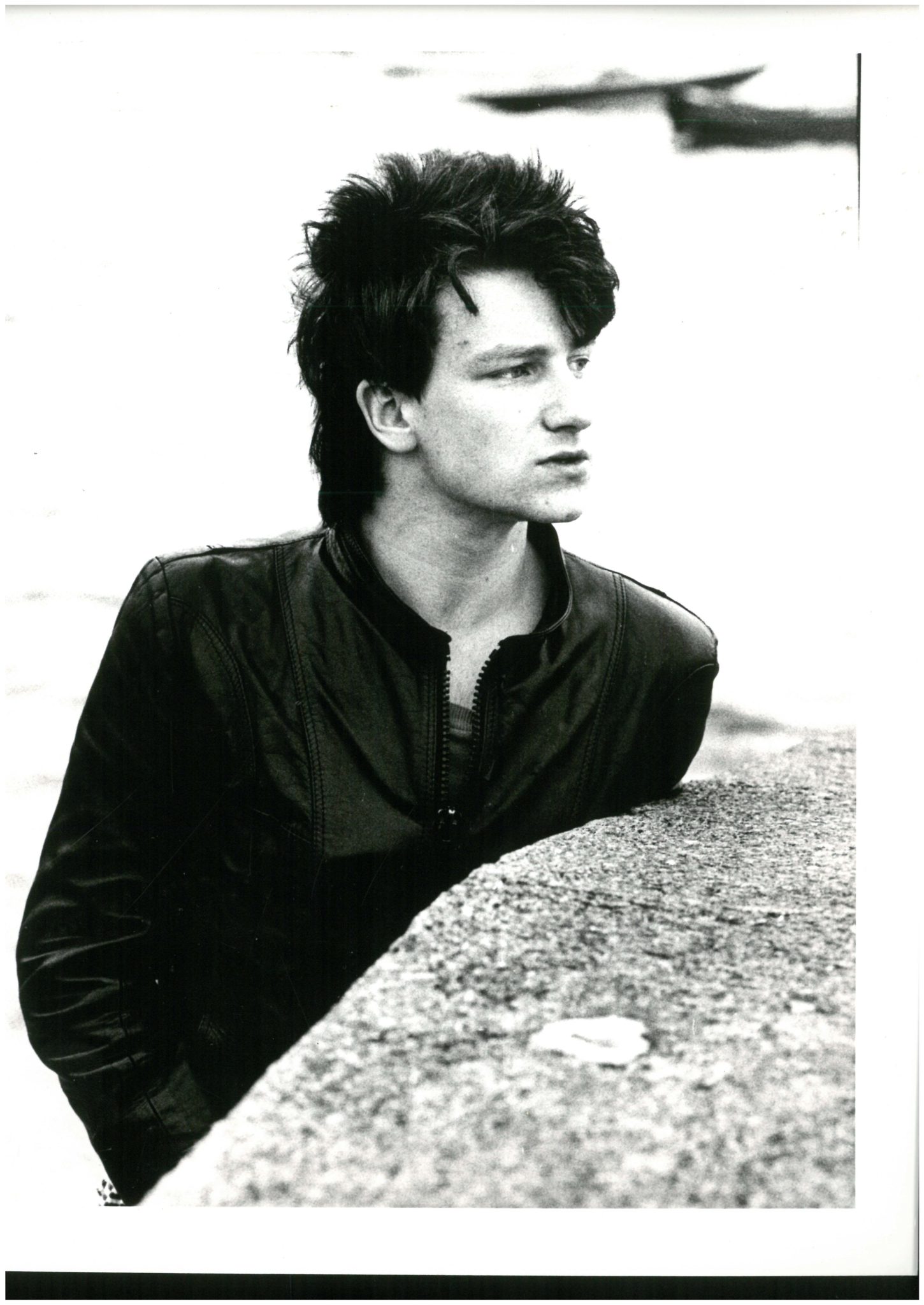

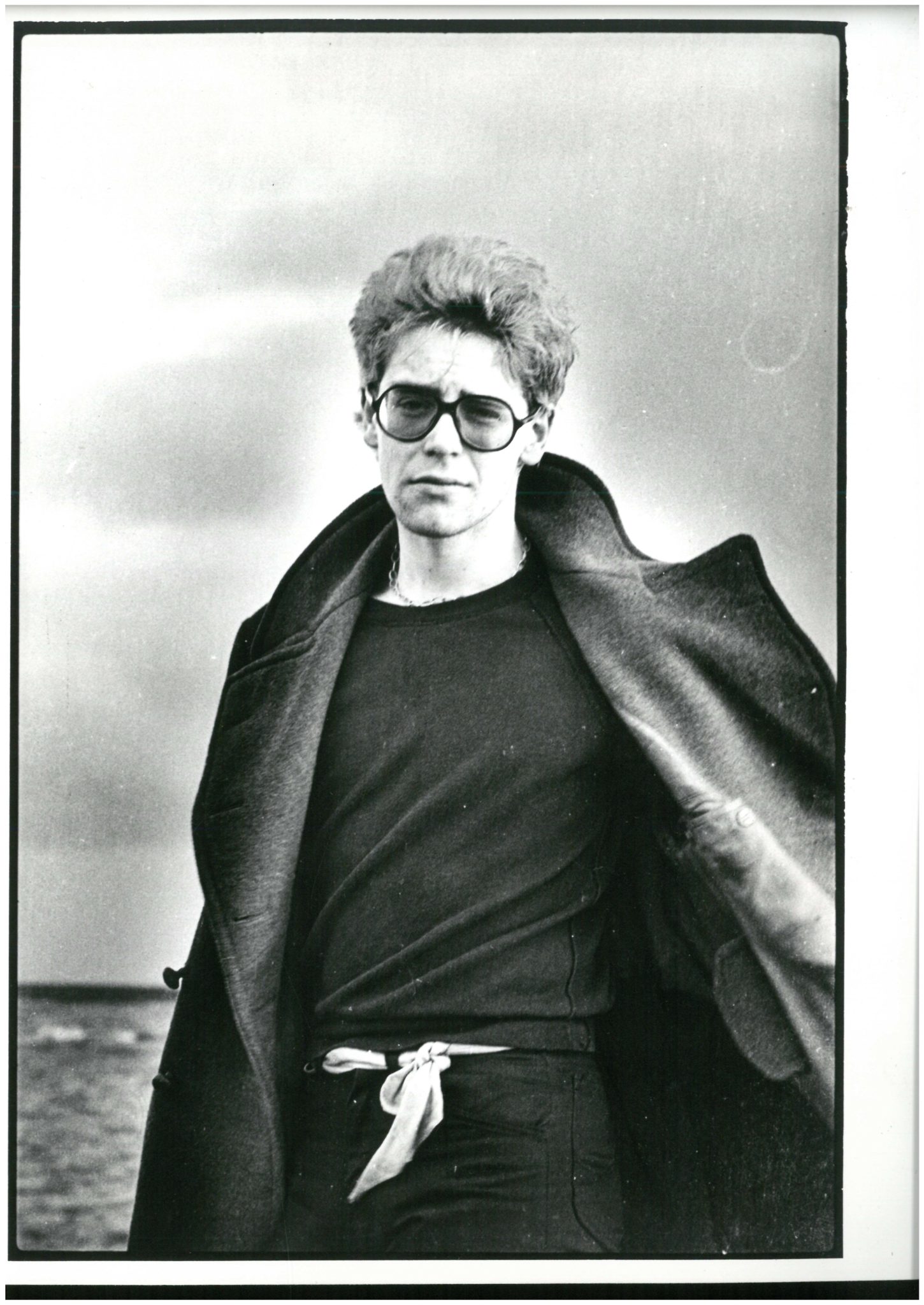

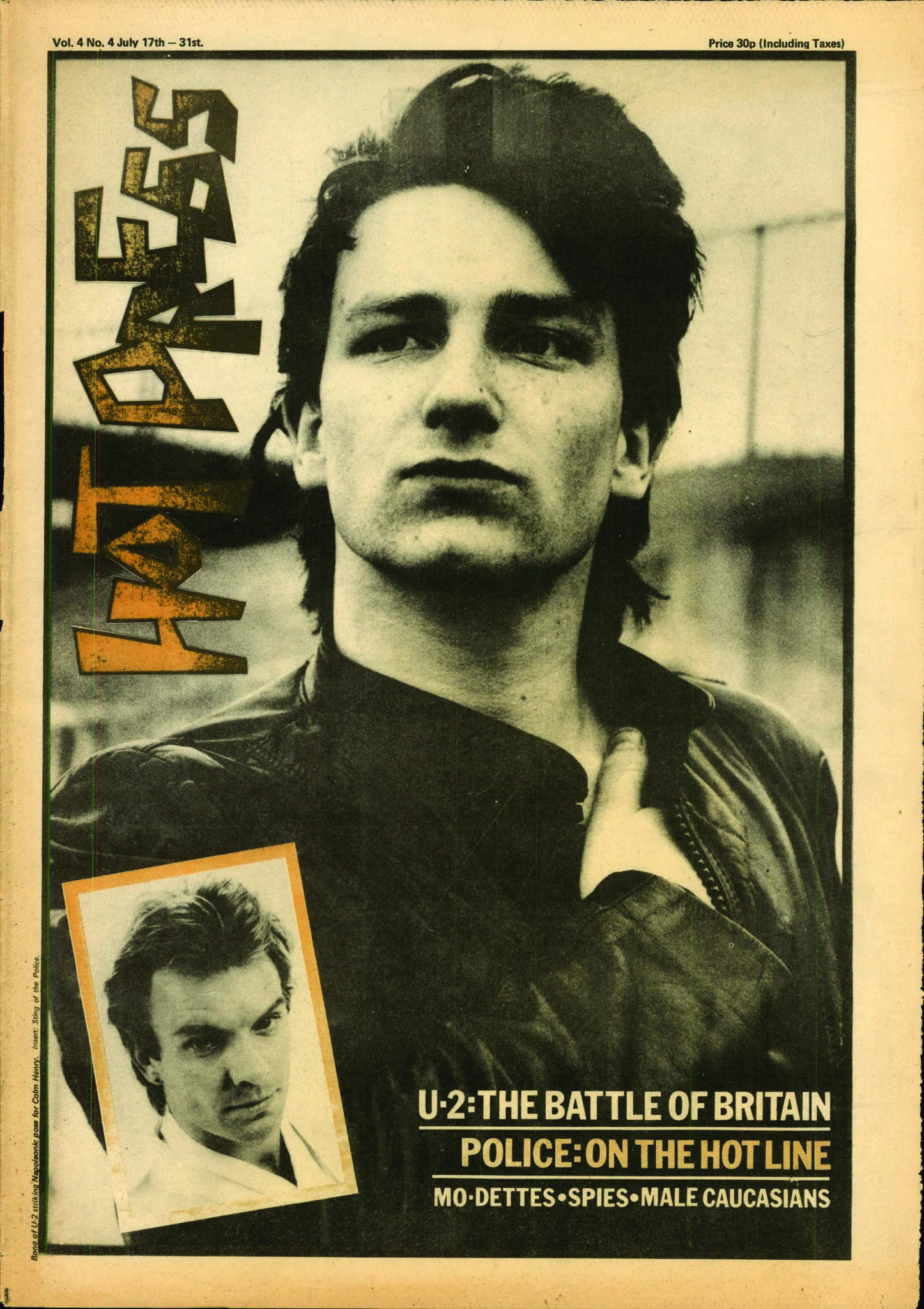

'The Battle Of Britain'. That was the cover headline Hot Press used to entice fans of the big beat to read about the young Dublin four-piece U2 in the early part of 1980 – after they had signed to Island Records but before they had recorded their stunning debut album Boy. It is a powerful and in many ways prophetic ‘on the road’ piece, which highlights so many of the nascent themes that would later become important to U2 – and ultimately to fans of the band. It was written by the late Bill Graham.

Twilight, another time another place, where emotions will touch, collide, jostle and electrify into tantalising shapes. Into the twilight zone where this temporary lodger strives to maintain detachment. Into a twilight zone between two countries and two cultures go U2. Into this twilight zone and you realise how mistaken it is to measure magic.

It’s the endlessly replayed battle between print and music. And can Bono’s ideal child read?

Recollected in tranquility are three totally dissimilar nights wherein U2 were disturbed, then contented and finally erupted.

You get scared and exhilarated. worried and enthralled and then so protective of the U2 child. You know he’s long past the walking stage, you know he’s restless and impatient to cavort and provoke. You know he wishes to will miracles, to change darkness into light. And you get unnerved and forsee the grey forces that abound and bide their time.

Stunned, you simultaneously admire and are alarmed by U2’s ambition. Some bands have a tryst with rock‘n’roll destiny and U2 could conceivably be one of those. Robert Fripp speaks of rock‘n’roll being the encounter between innocence and history. Unadorned, undistracted, U2’s themes are precicely that.

Advertisement

Let’s take the boat to England.

VISION OF UNWASTED YOUTH

We’ve arrived and to what?

Mucho publicity courtesy of Sounds magazine and a photo and accompanying paragraph in Time Out that’s a prestigious and encouraging recognition. This is essential because U2’s current game is “find the audience.” They’ve played London before, and built up the first traces of a following, but amid the competing tribes of the Capital, they’ve got to mark out, advertise and populate their own parish. None among us doubt the band’s capacity to win over any audience that arrives with open-hearted curiosity towards U2 – rather it’s getting them to appear that’s crucial.

And the following Thursday night at the Clarendon in Hammersmith, the gameplan appears to go awry. Afterwards we commiserate and realise that the date has not been publicised by Time Out and that Thursday is the low day before the weekend – but there’s a discouraging and unbalanced turn-out.

The Clarendon is a first floor fixture in a hotel of Victorian vintage and it’s rather like a miniature version of the Trinity Examination Hall with the same high ceiling and echoing acoustics. It requires about 500 to pack it but only 200 arrive and that’s including a high guest-list quota of interested bands and Island records staff. I wander around looking for teenagers – they’re hard to find.

And the combined circumstances of environment and audience make for a struggling, emotionally naked gig. There’s nothing inaccurate or unfeeling about the band’s playing, but the confrontation between band and the worldliest audience of the tour has its moments when the daredevil comes close to desperation. With wild determination, Bono keeps bringing his toys to them, keeps demanding ‘Look at this’ – but the chemistry is odd and you know he knows it. The audience has come to measure U2 against their burgeoning reputation as “At least this week’s thing” and won’t be willed into enjoyment. And at moments I’m wondering if some aren’t inwardly tut-tutting at Bono for lowering his front and making a disgracefully unreserved exhibition of himself. He reveals himself to the core, he shows his want; that isn’t playing the game according to the rules of that modern spectator sport called rock‘n’roll. It’s madness, another category entirely.

Advertisement

I feel small clouds of bemusement in the atmosphere and partially understand Sounds writer Dave McCullough’s anger at a similar date at The Nashville, where under-20’s weren’t permitted – the empathy necessary for shared euphoria is absent. Despite a small crowd bopping around the front, Bono just can’t feel the audience. Each number gains applause, but it isn’t enough. It isn’t nearly enough.

The lack is answered. Suddenly out of this unsettled climate wafts a moment of sublime dignity. A sequence of guitar chords – the linking passage between two new songs, ‘An Cat Dubh’ and ‘The Heart Of A Child’ – stealthily spirals upwards and for once the acoustics assist. Soothing, a peace offering, this vision of unwasted youth that sounds like ‘Albatros’ as reinterpreted by Eno transforms the mood and when the song is over there’s a muted, sighing cheer of recognition. Such sweet thunder!

Doubt diminishes, though Bono’s still fraught on the encore ‘I Will Follow’ and a triplet of fans joins them on stage. One wears a tee-shirt of Sid Vicious, the man whose manipulated, inauthentic, self-detonating rebellion represents all U2 stand against. A small stubborn step forward for U2 has been achieved.

BONO IN HIS UNDERPANTS

“It was tense, it was wrought iron, it was big because of the volume and the echo. It was vast. It was most peculiar. The audience were tense because I think they were in a place they weren’t used to being in. It was cold – it was a peculiar place upstairs in a hotel, a large dancefloor with light-shades, at the same time bare. It was the unknown, and the unknown is always very interesting. Last night was more of emotion, of the band relaxing into the audience and into the music.”

Bono can be the band’s best reviewer.

The first two dates are a complete contrast. At the Half Moon Club in Herne Hill, south of the Thames, a warm and comfortable pub where the dressing-room is the manager’s living room, U2 gain a full house and Paul McGuinness smilingly ambles across to inform me that this is a landmark night, the first time U2 have sold out in an English venue.

Advertisement

It shows in the music also. U2 play a much more contented, less abrasive set, their ardour somewhat cushioned in this cosy pub. I like the set, I smile more than the previous night but it’s not an environment to bring out the performing extremes in Kid Galahad and his companions, even though for the encore Bono leaps off stage to serenade the audience from the raised enclosure where the mixing desk and us flunkies are located. It’s a good gig, well done boys and all that, an opportunely-timed confidence-builder for the remaining two dates at the Moonlight Club and then at the Marquee, supporting The Photos.

About this point it’s customary to relate the on-the-road antics and anecdotes of the band in question. With U2 however, one isn’t dealing with a band whose alcoholically and/or otherwise-induced acts of privileged delinquency keep their publicists merrily feeding the gossip columns with froth. With the exception of Adam Clayton, who twice escorts manager Paul McGuinness in pursuit of nocturnal revelry, U2 aren’t tempted by the bright lights. For a rock band they are early risers and early sleepers – U2’s cautious rationing of distractions is further evidence of their dedication and the manner in which their energy is channelled so concentratedly into their music.

We’re also unlucky on the two nights we venture out. After Herne Hill, we drive to the Belgravia Carnival only to discover we’ve been misinformed. It finished the previous night. Then there was the great Lookalikes party mystery.

Friday, tour manager Jim Nicholson meets their drummer Mike Mesbur and elicits the information that The Lookalikes will be holding a party on Saturday night in their Wandsworth house. So at the appointed time off drives the whole party to discover a totally darkened and vacated house. Tails between the tyres of our Mercedes van, we return to the Earls Court apartment the band have rented for the duration, and ring around to learn that the list of social victims extends to The Tearjerkers, Moondogs and The Lookalikes publisher. Someone excuses The Lookalikes by suggesting they’ve probably overshot on their day’s recording session but as the unofficially nominated shop-steward for the disappointed, I can say that only a fully signed and witnessed statement will be accepted in explanation.

So all I can tell you and Dr. Conor Cruise O’Brien, on his Thames house-boat, is that Bono talks to The Observer in his underpants.

Saturday morning in the common room of the flat, everyone’s making or eating their breakfast and immune to the chatter around him, there’s Bono in his white y-fronts nattering away on the phone to Robin Denselow, writer of the Upfront rock snippets in The Guardian colour supplement. Readers of a sensitive disposition can rest assured that both he and the rest of the band were fully clothed for the Hot Press interview which follows...

Advertisement

YOUNG AND WIDE-EYED

U2 are rebelling against many things, but the school they all attended, Mount Temple Comprehensive, doesn’t appear to be among them.

“Mount Temple allowed a freedom to think out things,” Bono reflects, “because we got to know about things like girls and how they interacted with boys at an early age. So that didn’t become a hang-up.

“Obviously smoking wasn’t encouraged but at the same time – and I can only really see it now – it was not so authoritarian to make us feel, right we’re going out to smoke. We’re going down the pub at lunchtime to get drunk against these people, these oppressive faces – because they weren’t oppressive so what was the point?”

U2’s chemistry deriving from their beginnings as a school band may be their secret ingredient, but the receptacle for that chemistry, Mount Temple Comprehensive appears to have been a very special school. As Ireland’s first comprehensive, its pupils suffered none of the totalitarian emotional suffocation which has disfigured so much of Irish education. Nor were they conscripted into a religious system of joy; U2 come carless from their school.

“Adam really knows the two sides of the coin because he was also in another style of school,” advises the Edge – and Adam who went to prep school and then as a boarder to St. Columba’s till he was 16 confirms the difference of experiences.

“To be perfectly honest I rebelled against the privileged society (in St. Columba’s) even though I was part of it – which is totally hypocritical, I suppose. But I just thought there were a lot of people who weren’t really very important human beings. They were just living on something else, the fact they were part of that society was what gave them importance. And I don’t think it worked.”

Advertisement

Refer to Bob Geldof and his embittering experiences in Blackrock College. Refer coincidentally in this issue of Hot Press to Joey Barry of the Spies and his comments about the Christian Brothers – and marvel at U2’s fortune. They haven’t had to waste energy in emotion-consuming and distorting campaigns against Church and teacher. They hadn’t to suffer the confusion induced by a system that claims to teach people to be saints but in reality compels and trains them to be rebels. It also explains the odd angle from which U2 approach rock, and its notions of rebellion.

“That’s half the thrill of teenage drinking,” says Bono. “I can remember drinking because it was an exciting thing to do at an early age. It was something you weren’t supposed to do. At the same time I got very bored very quickly with it, whereas many of my counterparts in other schools around Dublin didn’t.

“No, I’m not from the same privileged background as Adam. He lived in Malahide whereas I lived in Ballymun, and the people around me didn’t get so bored with it so easy. I questioned even things like smoking. Obviously I used to smoke paper or whatever it was. But I got bored very easily with those terms of rebellion because, unlike my neighbours, I wasn’t being told all the time not to do this.

“I wouldn’t question anybody’s leisure time if there’s been a decision behind it. But I’m afraid where I’ve come from, there’s a very definite thing which is drinking tonight, drinking tomorrow night, drinking Thursday night, drinking Friday night. That is the trend of people at 18.

“Why? Because they’ve nowhere to go. Why? Because they can’t really think of anything else to do. Why? Maybe because things are apathetic now, so other forms of leisure – even football – are declining. That is a pattern they’re falling into and they’re not so much thinking about it as just wandering there, being headed there. And it’s a safe thing.”

And he continues by criticising the double standards of Governments that promote Health Education campaigns against drink and nicotine whilst simultaneously raking in vast revenues from the habit. Matters of attitude, the means to avoid contamination of the spirit and will – these are the points Bono is arguing, though he is careful not to be perceived as a crusading misanthropic puritan.

He adds: “I’m not anti-drink... all of us drink occasionally. But I don’t think we’re involved in what I call rock‘n’roll masturbation, which is that you’re in a band, you get wrecked with other members of other bands and it gets in the papers and everybody laughs ho ho ho.”

Advertisement

It was this exact refusal to participate in the rock‘n’roll swindle and to be manoeuvred into a sub-culture of gratuitous wasteful squabbling and easily policed and controlled rebellion that made U2 controversial through ‘78 and ‘79. They weren’t to be re-routed by the tyranny of fashion. Although it must be stated that U2 were lucky. It isn’t every individual who finds, as these four did, the right chemistry of friends, allies and circumstances.

Nonetheless Bono’s point about their differences with other factions in Dublin remains: “We are anti-laziness, we are anti-apathy with no direction. I am really glad to see that some people with whom we’ve had previous disagreements are actually doing something positive themselves. I’ve no time for cynicism with no direction. I’ve no time for people who complain and sit around looking into space. There’s a guy in Dublin who we all know, Brummie, who’s at least trying to arrange concerts. Whatever. I still can’t relate to the guy himself but I like that – that I can appreciate. But I’ve no time for people who are casual rebels. They remind me of the hippies of the past who would get stoned and sink into the day.”

The Edge enters with his contribution, the guitarist talking about the ‘pregnant’ Irish author: “It’s a term I’ve heard in literary circles and because he’s always in the middle of his novel he can always slag off everybody else’s. And you know he’ll always be in that position telling everybody what they’re doing wrong.”

Bono contrasts such attitudes with their own: “A lot of people knocked U2 at the start because we were young and wide-eyed and they weren’t doing anything themselves. At least U2 realised we had problems. We realised we were wide-eyed. We realised we must find people who did know and find out – and we worked hard and that’s the point.”

And Adam tells of his incredulity about ‘A ridiculous discussion with another Dublin band. “I was shocked,” he avers, “because they were advocating that the only way to get on in Dublin or the music business anywhere was by crapping on people.”

Saving that band’s embarrassment by naming them, his story concerns an incident wherein said outfit played petty power games to headline. Adam was arguing that “Goodwill among Dublin bands had been sacrificed” by their methods – but he was met by the counter-assertion that it was a victory, the band had headlined and ‘it was more important than the goodwill of people’. “And I said, if you’re thinking like that, it’s no wonder you‘re still in the position you are in Dublin. Because I think that’s terrible and it’s even worse to admit it.”

Bono takes up the theme: “Maybe it was sent down from the Rats that, to get on, you go your own way, you have a direction and you fight to get there. But we were never like that. We realised that as a self-sufficient band we couldn’t break through. Let’s accumulate knowledge, let’s talk to the people in the different areas and find out. And we found out knowledge, we discovered knowledge. We went to the right people at the right time. We got the right manager and that’s always been the way. And in music we always put in the same effort.”

Advertisement

But not everybody was sympathetically responding.

DEMORALISED AND BROKE

There was a crisis point when U2 almost crashed to earth, when the bravado of their idealistic plans met the music industry in recession and cynical turmoil. The six months before U2 finally came to reside with Island Records became a period when the organisation was under severe financial pressure.

As manager, Paul McGuinness’ assets have included not only his ability and prior experience, but also his lucrative career as a director of advertising films, a factor which both allowed him to invest money in U2 beyond their contemporaries and to approach his bank manager with more self-confidence than other managers when circumstances required.

But when, last Autumn, U2 planned their first venture to England, they were shook by their first taste of short-sighted London Machiavellianism. Their dates were meant to be financed by the advance of a publishing deal, but the company involved, at the last and most pressurising moment, halved the advance in the hope of swinging a cheaper deal. McGuinness put down the phone and in 48 hours he and the band made up the shortfall by borrowing £3,000 from friends and family.

A blow parried – but at the start of the year it was followed by the EMI debacle. Negotiations had already fallen through with both CBS Records and A&M, but EMI – through the advocacy of their A&R man, Tom Nolan – were taking a much more serious interest. Two other EMI executives travelled with Nolan to Dublin, whereupon the party sat down at the back of the Baggot Inn – and then departed to watch The Specials on the Old Grey Whistle Test!

Advertisement

The ironies of the incident were black, and morale-shattering. EMI, who despite Nolan’s insistence had already passed on The Specials, sacked him – and U2 retired to recover.

“We were demoralised and we were broke. What should we do then? Lie in our own self-pity?” Bono asks rhetorically.

“No,” he answers himself. “We decided what we were going to do. We were going to play a headlining concert tour around Ireland, and we were going to headline at the National Stadium and that was our way of fighting against the pressures, to go in exactly the opposite way and to show people we were full of confidence.”

And it was at the Stadium that Bill Stuart of Island arrived and according to Bono ‘offered us a deal on the spot’: “Which, and this should be noted, we complained about. We still knew what we wanted and we disagreed with this, this and this, like it or lump it, we’re going. And if they had left, where were we? But we believed, because we weren’t going to be second, we weren’t going to drop our aim. And in fact they have honoured that.”

But the soul of a band must be finally located in its music. The same application and dedication informs their working methods. At this point U2 could justifiably relax but each available week-day in Dublin, they trek out to their Malahide rehearsal room to continue their course of musical self-improvement.

This results in U2 possessing an intimidating amount of songs – over forty by their estimate – when the time arrives to decide on material to record for their debut album this August. And such prolific creation also means a set that is in a state of constant flux – so here in London, besides the affecting ‘An Cat Dubh/Heart Of A Child’ pairing, U2 are also debuting ‘Saturday Night’ and ‘I Will Follow’.

The Edge likens their work methods to that of a sculptor in his studio: “We get a block, or if you like three pieces of rock, and you’ve just got to chisel away with them and get them into shape.”

Advertisement

Larry Mullen who’s been sitting quietly so far explains a key change in his role: “Adam and Dave and Bono used to write songs and say Larry you come down at four and we’ll put drums to it. And in fact in a review by Peter Owens in Hot Press, he said, ‘I saw U2 before and I thought the drums were the weak link’. And that was very true because Dave, Adam and Bono were writing songs and I was coming down to put the drums on and I wasn’t seeing how the songs were being made. So now myself and Adam are writing songs together, so the bass and drums are working in a way they weren’t before.”

One detail, one anecdote, one teacher left – Mannix Flynn. This person remembers wandering through Stephen’s Green one Sunday lunchtime to find Bono and Gavin of the Prunes with their drama tutor. Bono flares with affection when I mention Mannix.

“Mannix Flynn is a guy I respect. I just love him, his whole thing. He’s Dublin to me – he’s great. He’s evolved from a very rough part of town. He has no cynicism – like he wouldn’t resent Adam because Adam lives in Malahide. He’s quite open on all areas, and he treats people like people. He has a cut of knowledge about the ‘space’ which is what he calls the stage. And how to be on that stage and how your body is on that stage and how to talk to people with your body. And we studied mime with him and with people that he knows.”

Adam concurs about the importance of Mannix, the former Project actor, collaborator in ‘The Liberty Suit’, ex-borstal inmate and occasional shop steward of Grafton St.

“I think in terms of somebody to talk to, he was crucial because his ideas and perspective on life are really important.”

Bono adds: “That was an important area for us. That’s why we studied the mime, to loosen us up, to try and perform on stage – and we’re only at the beginning of that."

As London finds.

Advertisement

A DYNAMO IN SEARCH OF A DESTINY

It was a rising at the Moonlight. A superlative, extraordinary affair that prompted Paul McGuinness to honour it by buying the band a bottle of champagne, a rare ritual for very special performances. The ‘Find The Audience’ game was over, the house was packed forty minutes before U2 took the stage, with Adam having to embarassedly placate a late-coming group of fans who’ve arrived from Herne Hill. U2 just raped, pillaged and plundered the Moonlight.

It was Bono’s instinct again. I don’t believe his associates ever wavered from the same level throughout the three dates – if anything they made more mistakes tonight than in the other two – but the theme of this tour is how Bono reacted with such intuitive accuracy to each environment.

He conducts and re-generates the mood, and tonight any anxiety or temptation to relax is passed. Every ploy in the book, including the Iggy swan-dive into the audience, works. He just energises through to that well-nigh fanatical power of rock, where you don’t know whether to savour, be exalted or frightened, now that the beast is roaming the hall.

You feel a rare power and intensity, one that doesn’t hide itself or role-play within accepted styles. You feel exhilaration, obvious pride and then shudder, because unlike 99.99% of the company, you know this is only the beginning. In Ireland, U2 and Bono have existed in a well-protected enclave; they can’t look back now.

Such is the emotion – the details are secondary.

You saw Larry smiling openmouthed like never before, you felt a band and a performer whose existential grasp of the drama of rock could push and shape this entertainment into shapes not previously premeditated.

Advertisement

You got careful, you got too fearful, too protective, too grave. You note an intensity, a desire for communion that extends far beyond matey, laddish revelry or anguished mutual therapy. A force unleashed, a force controlled, a dynamo in search of a destiny.

And a destiny in search of a new dynamo! Afterwards in the flat I ask Adam about the dressing-room comments. What did the fans say? What was their line? He says they were wary, they thought we’d be superstars.

And Peter Owen’s lady Linda suddenly gets embarrassedly reverent. She implies I almost shouldn’t be talking to Adam, elevates him as if by some unconscious media-induced instinct. And we all know she knows better; and I know she said she was too old to feel like that about a band.

Hell, we couldn’t even get to a Lookalikes party.

* * * * * *

GLOSSARY

Sounds Magazine:

Advertisement

Conceived in 1970 as a “left-wing Melody Maker”, Sounds was one of the ‘big three’ rock inkies in the UK at the time, alongside that paper and NME. It was generally outshone by the latter in terms of assumed hipness, but – as with the poppier Record Mirror – it provided valuable early UK support for U2. Among its star writers was fiery Northern Irish man Dave McCullough. Sounds closed in 1991.

Robert Fripp:

Originally guitarist with prog rock maestros King Crimson, Robert is regarded as one of the greatest players ever, going on to work with Brian Eno and David Bowie, Peter Gabriel and David Sylvain.

Robin Denselow:

Music critic with The Guardian, Robin also reported for the BBC on politics and international conflicts, winning awards for his coverage of Gulf War Syndrome in 1993.

The Lookalikes:

A talented Dublin band, Billy Gaff (manager of Rod Stewart and owner of Riva Records) famously came to Dublin to see U2 and signed The Lookalikes. They moved to London to make their debut album, but sadly never achieved commercial lift-off.

Advertisement

Joey Barry/ The Spies:

Joey was lead singer with The Spies, a band from Howth close to where Adam Clayton and The Edge lived. He went on to front Thee Amazing Colossal Men – which also featured sometime U2 producer and mixer, Garret ‘Jacknife’ Lee. The Spies also included guitarist Gerry Leonard, later MD with David Bowie.

Eno:

As the tenor of this article confirms, Bill Graham (who also lived in Howth) was extraordinarily prescient. Among the details here is – with the benefit of hindsight – a truly remarkable reference to ex-Roxy Music man Brian Eno, a whole four years before he worked with U2 as producer of The Unforgettable Fire. There were, indeed, times when Bill surpassed even himself...

CBS Records:

U2’s first EP, U23 was released by CBS Records in Ireland. But – hard as he tried – Jackie Hayden (later of Hot Press) couldn’t convince the company’s UK bosses to make U2 a proper offer. Until The Unforgettable Fire album, U2 records were released on CBS in Ireland. CBS was later subsumed into Sony Music.

The National Stadium:

Advertisement

Ireland’s largest music venue throughout the ‘70s, and regarded as the pinnacle of what an Irish rock band could aspire to: it hosted extraordinary gigs by Rory Gallagher, Thin Lizzy and Horslips, among others. Including it in their Irish Tour was a brave move by U2, who attracted more than 1,000 people. It was a seminal moment for them.

Then and Now:

Revisiting an article of this kind, from 40 years ago, presents all sorts of potential dilemmas. For one, do you go with the original headline or not? In this case, we have applied the headline that we used on the front cover, rather than the one that accompanied the article inside. There are also other minor tweaks: the cross-heads are new, adding a bit more structure to the article than we were capable of back in the day. There was another, more significant dilemma. Towards the end of the piece, Bill describes U2’s performance in what we might call Viking terms that none of us would dream of applying now. It was the language of the time, used by Bill with what I can say with conviction was complete innocence. Rather than changing it, the feeling is that it should be left as it was – with this acknowledgement that the awareness which has since developed of how implicitly sexist language can be is hugely important and welcome. As Bono acknowledges more than once in the article, we live and – hopefully – learn.

With two anniversaries rolled into one, 2020 is an important moment for U2 – marking 40 years since their extraordinary debut album Boy, and 20 years since their marvellously resonant All That You Can’t Leave Behind. To celebrate, we released the Hot Press U2: 80-00-20 Special – out now!