- Music

- 23 Apr 19

Before it was released and before it came to be considered one of the best albums ever recorded, there was the painstaking process of writing, redrafting and editing the songs that would constitute Blood On The Tracks. As the new box set More Blood, More Tracks demonstrates, Bob Dylan was extraordinarily meticulous and intense in his dedication to painting this masterpiece. But there’s more: in a world exclusive, Hot Press gets the first ever opportunity to view additional private notebooks, in which Dylan’s unique, perfectionist approach to his art is dramatically revealed.

“Now somebody else is going to be allowed to see what I said to myself.” Bob Dylan to Paul Robbins, 1965

Bob Dylan said this about his novel Tarantula, which was not officially published until 1971. One reason for the delay was that Dylan didn’t want it released; already a famously private public personality, perhaps he’d had second thoughts about letting anyone else see what he said to himself.

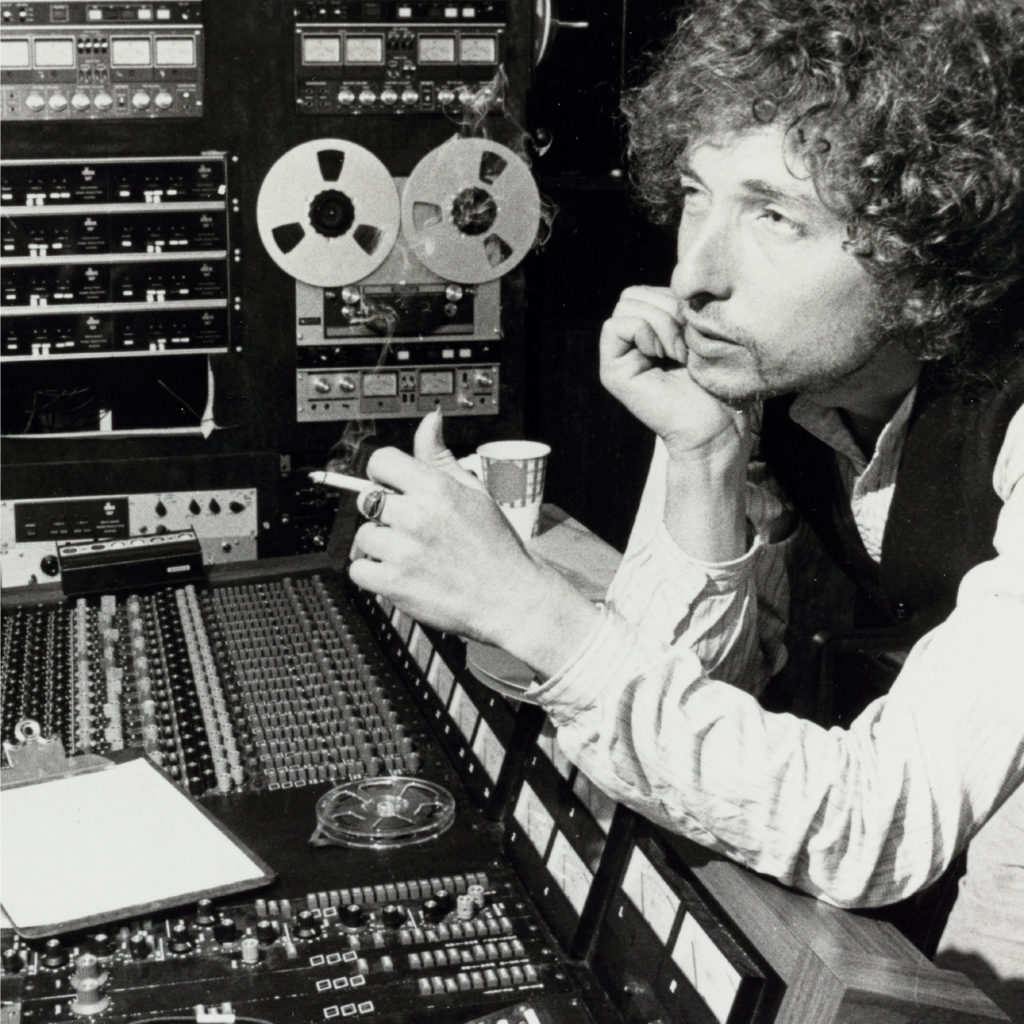

Literary archives are the most intimate way for a scholar to gain access to a writer’s creative process. The Bob Dylan Archive in Tulsa, Oklahoma, now open for research on a strictly regulated basis, provides astonishing revelations about Dylan’s care in drafting, revising, rewriting, and perfecting. In pristine acid-free grey boxes and brand-new mylar sleeves rest notebooks, shards of note pads, hotel stationery, business cards, even bits of brown paper bags, covered in Dylan’s small, hard-to-read handwriting. As James Joyce did, Dylan writes on anything and everything to hand, when the words and phrases strike, which seems to be any time, all the time. I could absolutely have stayed forever and never realised the time, but my purpose, on a first visit, was to review the Blood On the Tracks song drafts written in two spiral notebooks that have, until now, been inaccessible.

Blood On The Tracks was released in January 1975, after a brief but convoluted recording history. Dylan worked on the songs through 1974, writing lyrics in a series of tiny spiral notebooks. In September 1974, Dylan took what he’d been writing to the A&R Studios in New York, where, with producer Phil Ramone, he made what could have been a solo acoustic blues record. Then, in Minnesota that December, with the help of his producer brother David Zimmerman, Dylan assembled a group of local Minneapolis musicians and re-recorded the songs with rock and roll soul.

Advertisement

Five from the New York sessions and five from the Minnesota sessions ended up on the record. Some tracks from the sessions have long been bootlegged, but all the takes — clean and clear, and unveiling the raw blues Dylan once composed — have now just been released by Sony/Columbia/Legacy on the new official Dylan bootleg, the box set More Blood, More Tracks: The Bootleg Series Vol. 14.

In April 1975, promoting the album, Dylan gave his first radio interview in nearly a decade to a friend, Mary Travers (of Peter, Paul and Mary). After she told him how much she enjoyed Blood On The Tracks, Dylan replied, “A lot of people tell me they enjoyed that album. It’s hard for me to relate to that. I mean, that, people enjoying the type of pain, you know.” Blood On The Tracks contains some of Dylan’s best-known, and best-loved, songs: “Tangled Up In Blue,” “Simple Twist of Fate,” “Idiot Wind,” “Shelter From the Storm.” There is the bright “Buckets of Rain,” the lament “You’re A Big Girl Now,” and the long ballad-cum-Hollywood western that plays its scenes just like a moving-picture show, “Lily, Rosemary, And The Jack of Hearts.” From its release, critics and fans have called Blood On The Tracks a breakup record. It was indeed composed during Dylan’s initial separation from his wife, Sara, and their family together (he and Sara remained married until 1977), but is also an artistic project, and forcing any one-on-one correspondence with autobiographical fact is a seductive, and inappropriate, game. The notebooks tell a story of layers of life in upheaval, all rolled together in a fiercely, even terrifyingly, creative torrent. When the singer of “Maggie’s Farm” (1965) says “I got a head full of ideas / That are drivin’ me insane” that feels about right, as one reads Dylan’s drafts for this album.

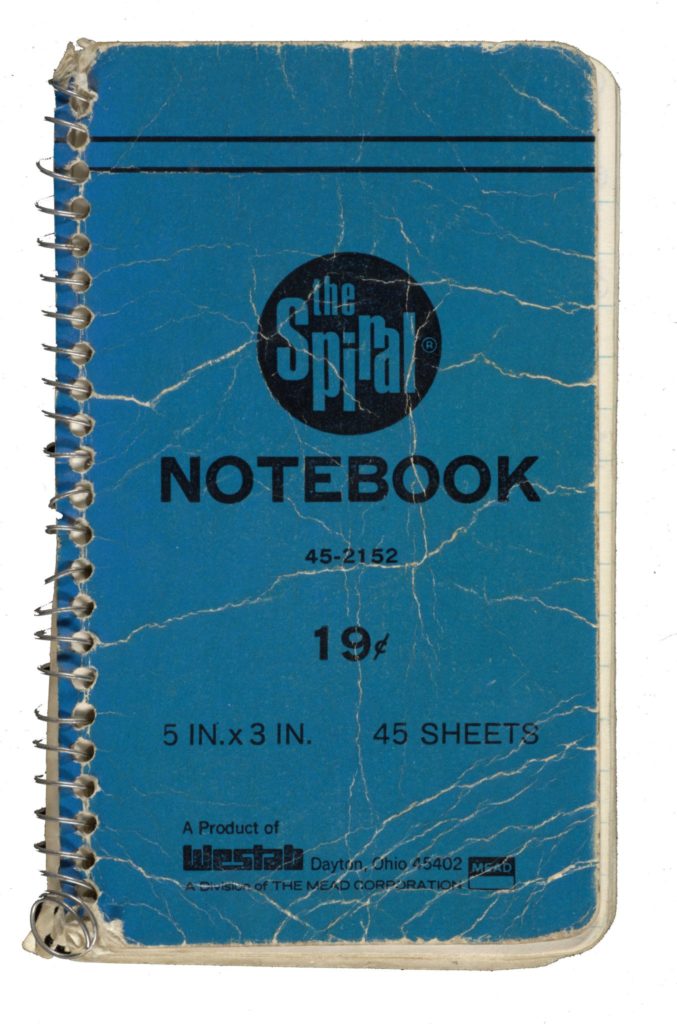

There are three Blood On The Tracks notebooks of which we are now aware, in which Dylan drafted, revised, and scrapped songs for the record. All are the same kind — “the Spiral” notebooks, made by Westab (a division of the Mead Corporation, then based in Ohio), three inches by five, and sold in the 1960s and 1970s for nineteen cents. Thin spiral wire runs up the left-hand side; the paper is lined. You could shove them in a hip pocket, and from the condition of these, Dylan clearly did, and sat on them often, too.

____________________

One notebook, with a tomato-red cover and long out of Dylan’s hands by means unknown, is at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City. This has long been referred to as “the” Blood On The Tracks notebook. I have been working with this notebook since 2014; it has now been reproduced in full in the deluxe edition of More Blood, More Tracks (four pages accidentally omitted from the printing are available at bobdylan.com).

But the Dylan Archive holds two more, and these virtually unknown and unpublished twins are my topic here. One is coverless, though the ghost of a red-orange edge remains trapped beneath the wire. Very battered and fragile, it is a working book of lyrics but also of lists of art supplies, thoughts and telephone numbers, observations, addresses, and reminders of various kinds. The other is pale marine blue, and is a gold mine, a quarry, a map of creating, a veritable trove of compositional ferment. Taken together, they show Dylan’s drafting process and artistic creation in a richness and detail that it has not been possible to chart until now.

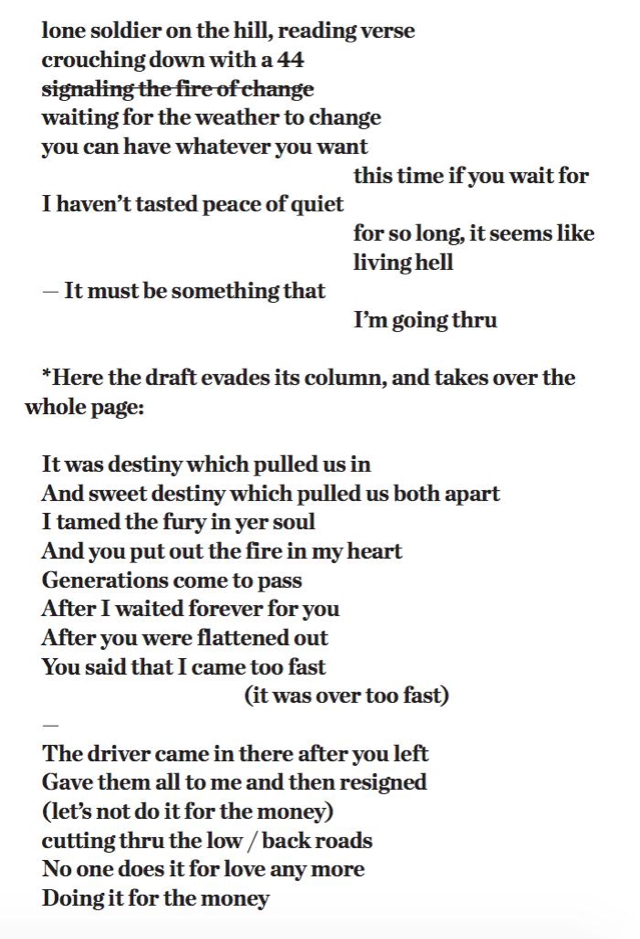

The two Tulsa notebooks, catalogued simply as Notebook 5 (the coverless one) and Notebook 6 (the blue one), are undated, with few clues as to exactly when or where they were written. Almost every page of them is heavily revised, with sometimes scarcely legible scribbles above, below, and in the margins next to the lines, in the middle of the pages, that were presumably written first. Dylan uses plain black or blue ballpoint most often, with corrections and changes in the same colour. Sometimes he uses a pencil, and the legibility worsens. His words, phrases, parentheticals spill out in the same thought-go, or were maybe added an hour, a day, or months later. The extent of his revising is staggering; and one thing pouring out of his songwriting is the perfectionism. Even his fellow Nobel laureate W.B. Yeats’s convoluted drafts are not so ubiquitously utterly changed.

Advertisement

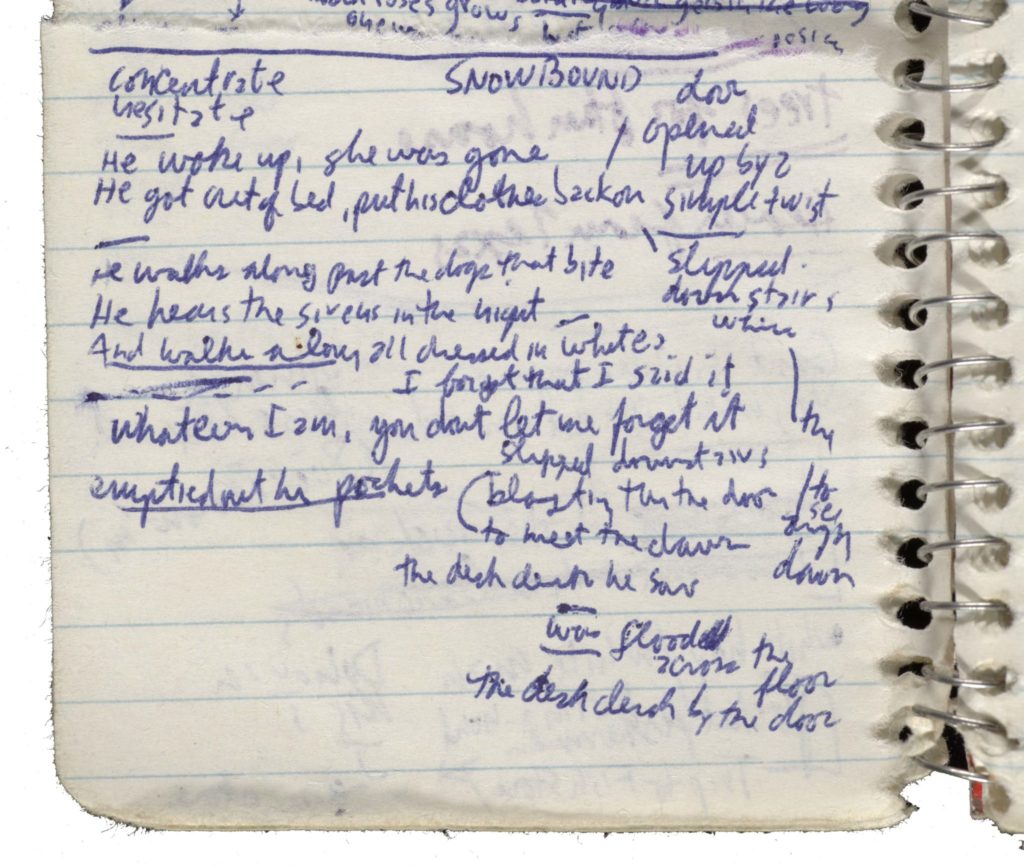

In places Dylan’s tiny printing is as tidy as if he had already planned the lines in his head, while in others he melts into a swifter, far harder-to-decipher semi-cursive. What is clear, however, is the astonishing fact that Dylan was conceiving and composing multiple songs at the same time — in the same breath, same thought. In many instances, he does not separate songs, or will do so rudimentarily, with a dash or in a parallel column on the same page. He veers from “Simple Twist of Fate” to “Tangled Up In Blue,” to “Meet Me In the Morning” and back again. Everything is happening in his head at once.

_____________________

Some songs come easier than others. “You gonna make me lonesome when you go” is a rush of neatly written, little-altered lines down the early pages of the blue Notebook. Yet even here, bright couplets come to him so thickly that not all can be retained. They fly by as Dylan thinks, edits, changes the song even as it is assuming the shape, and rhythmic sound, he wants. “My mind’s been in a maze / From holdovers and bygone days” gets left behind, as does the dramatic, painterly “But now we’re in the 2nd Act, / More real, less abstract.”

Art terms abound, which is unsurprising, since Dylan was painting seriously at the time. In his 2004 autobiography Chronicles Vol. 1, Dylan credits artist, activist, and author Suze Rotolo for inspiring him to begin drawing regularly, in their apartment on West 4th Street, in 1961: “I actually picked up the habit from Suze[.]” A native New Yorker from a left-wing family, Rotolo also introduced him to New York’s art museums, theater scene, and her politically active friends. During the summer of 1974, Dylan took painting classes in the Carnegie Hall studio of Norman Raeben, and has acknowledged, long ago, the way those classes influenced his songwriting.

He was also in between movies. Dylan survived Sam Peckinpah and Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid, which was filmed under wild, fraught conditions in and around Durango, Mexico in November 1972. Playing the role of “Alias,” Dylan also composed the soundtrack, and the project very much suited his imagination, fed on the Hollywood westerns of his boyhood and the ballads of the range, from those of anonymous 19th-century cowboys to Hank Snow and Johnny Cash. Shortly after Blood On The Tracks was released, he would begin the Rolling Thunder Revue tour and concurrent filming of Renaldo and Clara, the performance-art documentary/mockumentary he starred in and produced. Blood On The Tracks is the most thematically visual, and cinematic, of all Dylan’s albums; and indeed, it was announced in October 2018 that Luca Guadagnino will be making the record into a film, with a screenplay by Richard LaGravanese.

A lot of the camera’s work has already been done by Dylan’s words. The bootheels and hoofprints of Pat Garrett are strong in a song like “Lily, Rosemary And The Jack Of Hearts,” and the arthouse cobalt shades, days and nights on the road again, and costumed alter egos of Renaldo are presaged in “Tangled Up In Blue.”

Advertisement

“Tangled Up In Blue” is the side A, first track of Blood On The Tracks. A long liquid ballad of a love affair broken and resumed, broken and sought anew (or at least again), it is a song Dylan has still not finished. New lyrics appear in his live performances — a personal favorite of mine is “She was working in the Tropicana / I stopped in for a beer / I told her I was headin’ down to Atlanta / She said, “I’m gonna stay right here.

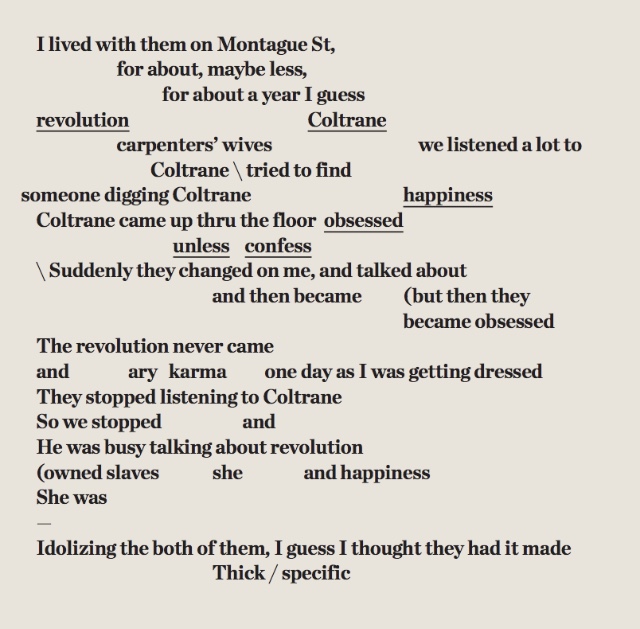

” For Mondo Scripto, his current show of writings and drawings at London’s Halcyon Gallery, Dylan has released a much-revised version of the song — one that has some roots in his earliest drafts. On the first page of the coverless Notebook, with mentions of a movie trailer, a Volvo, and daily appointments, are the words “2 miles off Delacroix” and then a draft of what would become the sixth verse of the alternate “he/she” version of “Tangled Up In Blue,” released on The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3: Rare & Unreleased 1961-1991. Eighteen pages later, it reappears, and Dylan is working on the same verse:

Dylan doesn’t specify what John Coltrane record is on the turntable, but anything by Coltrane intimates revolution, from the swiftly classic Blue Train (1958) through his avant-garde jazz, recordings of chant and prayer, to the wild Ascension (1966). In the earliest takes recorded of “Tangled Up In Blue,” the song is so blue it’s almost a dirge, Dylan’s voice low and rich, fading almost to a whisper and filling out to emphasize the phrasing. Perhaps with Coltrane’s tenor saxophone still in his mind, he drops onto the page a few lines, featuring another kind of horn, that would find their way into “Idiot Wind”:

I been double — mind

I’ll kiss the howling beast goodbye and roll the dice

While trumpets blow and imitators steal me blind

And, then, Dylan draws a line horizontally across the page and concludes with an inning from a goofy baseball game, a little sketch reminiscent of Abbott and Costello’s “Who’s on first?” in which characters called Zero, Joe Luck and Parka all get hits.

Advertisement

When he gets back to the song featuring Delacroix and Montague Street, Dylan plays with titles: “Blue Carnation I,” “Blue Carnation Blues,” “Dusty Country Blues,” and “Dusty-Blues.” A blue carnation is such a 1970s flower, unnaturally dyed and far from the coded 1890s zing of a green carnation. It’s also a prom flower in America, a cheap boutonniere worn by teen boys on their way to the dance. On the page in the blue Notebook where a title first appears, Dylan begins “Blue Carnation I” with the lines:

You were married when we first met

Soon to be divorced

If only I would’ve

Using too much force

I helped you out of a jam I guess

But I used a little too much force

And we drove Til we ran out of gas out west

And we split up on the side of road (sad night)

Both agreed it was

And I was walkin I turned around

Wondering what you’d do

If I turned and I’d only listened to the voice inside

On the right-hand side of the page, next to these lyrics, he has written: “Tangled Up in Blues / Guess I always been too Tangled / up in Blues.” Another draft page is topped with dashed rhyming possibilities: “—Jew — who — few — clue — do — flew — grew — new — rue — sue — too — you — zoo — slue — glue — this view[.]” This is just one of many instances where Dylan spins out a line of rhymes, testing words to find the one he likes best.

Shards of never-completed songs, a long Beat-style rap story about having his ego cleaned at the “laundrymat,” and significant work on “Simple Twist of Fate,” “Idiot Wind,” and “Lily, Rosemary And The Jack Of Hearts” intervene. Dylan’s next prolonged effort at the blues number is called “Dusty-Blues”:

And I was walking by the side of the road

Rain falling on my shoes

Headin’ out to the old east coast

Lord knows I paid some dues

Wish I could lose, these dusty sweatbox blues.

The deep personal attention to the I (not “he,” though Dylan continues to shift the pronouns in performance of “Tangled Up In Blue,” just as he did throughout the drafts) culminates in being settled down somewhere in a cheap hotel and “listening to James Brown.” “I got somebody’s mind working in me / But I don’t know whose” is the last line of “Dusty-Blues.” After this powerful statement of strange collaboration referring to whose thoughts are composing the blues, Dylan draws a line across the page, and rolls right back into “Lily, Rosemary And The Jack Of Hearts.”

Advertisement

_______________________

Slipping, sliding pronouns are a hallmark of many of the song drafts in the notebooks. “I” is romantic, or rather Romantic, for the subject, and pulls one in closer, as does “you,” making you the object of what’s being sung. Third person pronouns have a built-in distance that protects. In the notebooks, Dylan will initially commit to using, say, an “I,” but qualifies it almost instantly with “he” or “she” or sometimes “you” in parentheticals, preserving his options. Sometimes, less often, he alters the third person to the first. The turn in his released versions of “Tangled Up In Blue” where “he” becomes “I,” in the verse beginning “She was working in a topless place,” makes for a significant difference in the song. In 1978, Dylan told an interviewer in Australia, “The he and the she and the I and the you, and the we and the us — I figured it was all the same anyway — I could throw them all in where they floated right — and it works on that level.” However, his professionalism says something else, as you listen to Dylan recording rather than giving a quotation to a reporter. More Blood, More Tracks includes a take in which Dylan sings “He was married…” instead of “She.” Immediately he stops, says, “Aw, she was married.” They start the whole song over again.

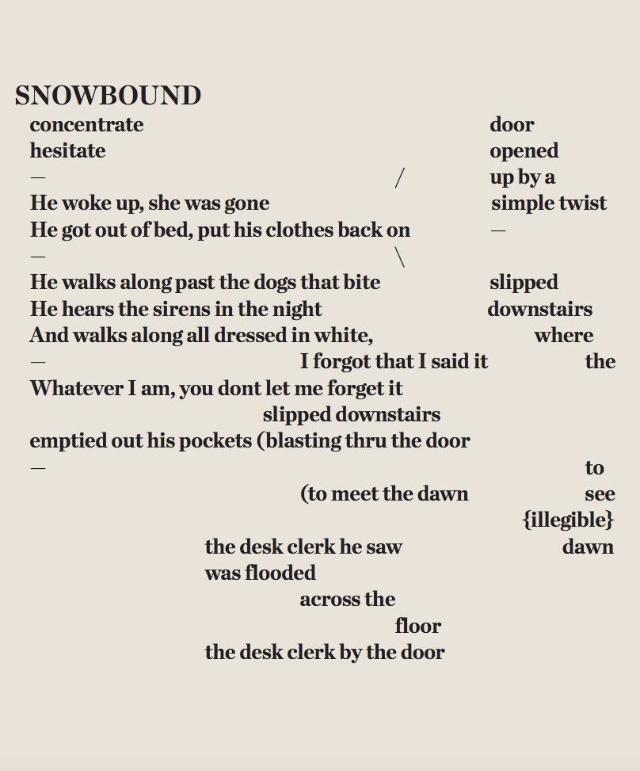

The drafts for “Simple Twist of Fate” are poignant and nostalgic. The song first appears as “Snowbound,” though the words “door / opened / up by a / simple twist” are in the right-hand margin. Dylan later titles it “4th Street Affair,” recalling the address of the apartment where he and Rotolo began to live together in early 1962. The song is not directly about her, though, or any other particular she. Dylan may be a romantic, but he’s also a pragmatist. He changed the title to hide the song’s “true” meaning? More likely he changed it because he’d already used a “4th Street” in a song title already. He also tests the titles “SCARLET WIND” and “STREETS OF THE WORLD” — these preceding a draft of the “hunts her down by the waterfront” verse that includes a condemnatory “She’d gone back to the streets.” However, Dylan gives the most space to the morning-after verse:

Decades later, on a piece of stationery now in Tulsa from the Hotel Drei Könige am Rhein in Basel, Dylan redrafted “Simple Twist of Fate” almost entirely. He concluded the verses “People tell me it’s a crime / To feel it for too long a time / She shoulda caught me in my prime / She woulda /stead of [.]”

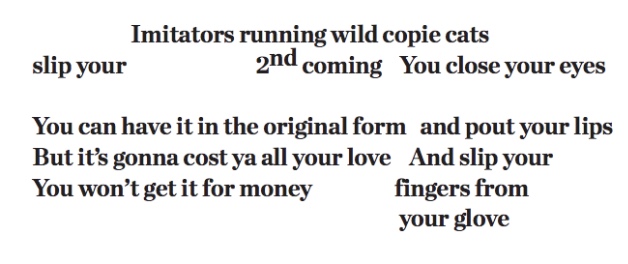

The idea of imitators and people stealing from him, coupled with the image of a proud, rejecting woman, are the kernels that generate “Idiot Wind.” Early in the blue Notebook, Dylan muses:

Advertisement

The repeated complaint that “I’ve had so much stolen from me, I just about lost my mind” often turns assertive in the end: “The original is still the best.” He seems to have no doubt, here, about what or who that original is. However, you really can see Dylan talking to himself, often deprecatingly, in this stretch of the blue Notebook: “How easy it is to fool (people) yourself — You’re still out of cigarettes and yr still in California.”

After a draft of “Up To Me” that focuses on possibilities for end rhymes, Dylan announces on the next page of the blue Notebook the title “FISHING ON A MUDDY BANK.” However, “Idiot Wind” is still on his mind. In the right-hand margin he adds, in a swift scribble,

buttons of

our coats

that we wrote

letter

dust — shelves

Dylan often shorthands a line he’s got in the form in which he wants it, as seen in the “dust — shelves.” He then starts something else, beginning “Long legged fox in a blue silk dress,” that, alas, goes nowhere. Nor does the start of an interesting train story that reads more like a diary entry, Dylan en route home to Woodstock, not so long before: “A fellow next to me looking at his watch surely he saw what I was carrying and suddenly bolted up and moved to the next car. Just then a conductor came in and told me I’d have to get off at Poukeepsie.”

Opposite this column, carefully divided off with a line drawn down the middle of the page, is the start of another section of “Idiot Wind”:

Advertisement

Dylan continues writing the song with figure of a soldier, alone and in company; the Red Cross store; and throws in the I Ching, circling crows, prisoners of love. He labors over the “haven’t tasted peace and quiet” line, and reiterates the concepts of mistaken identity, trust, and the deprecations of the addressee — “you said I was a flash in the pan”; “and that nothing about me would ever last”; “you said I was pretty bad[.]” His frustration with, but also acceptance of, destiny is constant, and leads to a sort of reconciliation, at one point:

I’d conquered time & space

If I hadnt taken your advice

But I don’t cry over spilt milk

We’d a conquered t & s if we only couldve seen where it went

But it was destiny that called to us, nothing in this life’s an accident

Set off in the left-hand margin is a couplet, and an endpoint that will survive in the final version:

blowin

the circles

of your eyes /

hot and dusty skies

—

Dust upon the shelf

We’re idiots babe

it’s a wonder we can

even feed ourselves

Quick as his thoughts, Dylan is on to the song that would become “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go,” and, next, the start of another song called “You Were Good To Me.”

1) You were good to me

I’ve never known it in my life

I been too long without a wife

And you were good to me

You were all there

2) No strings attached

Everything about it seemed to match….

Advertisement

He’s swirling, hurrying, and the loosening handwriting shows it — he starts another song called “Blind Alley,” puts in some stray lines from “Don’t Want No Married Woman,” and nails a couplet: “And the gypsy played his violin / And a thousand people stood soaked to the skin.”

“Idiot Wind,” though, is the song that won’t go away. It weeps into all the others, particularly “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome.” Sequential page 12 of the blue Notebook is practically a mash-up of the two, with “It’s been so long since I’ve tasted peace & quiet / I can’t even recall the smell / And Jesus Christ could burn ^ could be^ in hell” jarring against “lonesome for the {world} that never was and lonesome for the snow / You gonna make me lonesome when you go[.]” Later, “Idiot Wind” ends up pushing aside a draft of “Simple Twist of Fate” in which Dylan is shifting pronouns and who does what to whom. He also can’t decide the name of the man to be shot, nor the country to which the wife is taken, nor the circumstances of the money:

They say I shot a man named Grey ^(Hemp

(Kemp

And took his wife to Japan Italy

She inherited a million bucks

I took it from

And when she died, it went to me

A flash of temper, gentled by sympathy, follows. “They’re so confused by what they’ve read / Wishful thinking / They think I’m someone I’m supposed to be…. I don’t know / Maybe it’s the same for you.”

Dylan kept changing these songs up to and even past the versions submitted for copyright. The copyright pages for the Blood On The Tracks songs are rife with dashes left for words, even entire lines, most likely because Dylan’s offices knew better by then than to call lyrics a final version; and these must have been transcribed from recorded versions, in any case. “Check with Bob” and “ask Bob” in various handwritings abound. Some of these can engender a laugh in the library. In the copyright pages for “Shelter From The Storm,” for instance, someone has hazarded, clearly from a sung version, the line “A preacher boy to form.” Dylan has patiently printed the correction “A creature void of form.”

“Up To Me” didn’t make it onto Blood On The Tracks, even though Dylan worked hard on it, and revised it extensively in the Morgan Notebook. It was recorded for the album; there are nine takes of it on More Blood, More Tracks. “Call Letter Blues,” alternately “Church Bell Blues,” was also left off (both songs were released later). “Blind Alley,” “Blazing Star,” “Sketches,” and other possible titles start unfinished pages. Gems scatter, and are simply left behind. Some are full verses:

Advertisement

Perhaps you’ve seen me walking

On the highway in yr mind

Had some big ambitions

But they all broke like glass

Always done my duty

And tried to be kind

I couldn’t stop the progress

Of a nation going blind

Many are couplets; Dylan has acknowledged his appreciation for Shakespeare and Byron, and it has always shown. Surely it does here:

Dolores was (standing)^{cooking}^ with the Ace of Spades

She opened the window and I climbed up on her braids

I busted my balloon just to see it bleed

The writing’s on the wall but I never did like to read

Been all around the world and I was nearly on the verge

of wandering forever but I didn’t have the urge.

Single lines resonate all on their own:

“Too many worlds and they’re all too alike” ;”I feel like an actor, and the midnight train is loading”; “Blood On the Ice (cant lose what ya never had)”; “Poet of no Return”

Advertisement

Card-playing scenes and hands dealt by fate, fate, destiny, beauty, God, wry phrases, comments on never wanting to see another Bergman movie, and on contemporary politics, golden couplets, and so much more — the Blood On The Tracks notebooks can only be glanced at in an essay of this length. One thing is for certain sure: Dylan is still revising today, in performance, and in the texts he’s just released publicly for his Mondo Scripto show. He’s using words and phrases that might be brand new, or that he might have written in these notebooks four decades ago. Read his changed lyrics at the Halcyon Gallery, and listen to the versions on More Blood, More Tracks, to hear for yourself what is old, what’s new, what might be borrowed, and a whole lot of blues.

These days, when Dylan sings “Tangled Up In Blue” with the instruction “memorize these lines and remember these rhymes,” he’s grinning at you. As soon as you’ve gotten them set in your head, he’ll change them on you. Those songs you know by heart? He’s been knowing them longer, and has plenty more to put into them — lines he created in 1974, and lines he’s written some time since. He’s The Joker, The Riddler, both masks he loves to wear on stage. His lyrics for not just the songs in these notebooks, but for others, remain protean; he’s still revising and shifting. Self-proclaimed purists who love their favorite songs and gripe about Dylan’s changes after concerts, beware: these might not, in fact, be “new,” but might just be Dylan’s initial ideas that he’s decided, only now, to share with us. He’s been revising forever, reworking his songs since they were “finished.” He is a Nobel Laureate “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition,” and he’s keeping it new, or, in a Modernist directive, taking his own art and making it new.

Dylan’s lifelong refusal to be categorized or canonized applies to his individual songs, too. He doesn’t want his lyrics carved on monuments or tattooed on your bodies. He’d rather they be alive in his own mind and in your ears, writ in water, blowing in the wind. The Notebooks are a goldmine revealing much of how the songs of Blood On The Tracks first came into being, and, as intimately as we’ll ever see it, both the fertile welter and professional perfectionism of Dylan’s creative process.

*Author’s note: Where round brackets or parentheses occur within quotations, these are Dylan’s own. In the case of an illegible word, or my best effort at a transcription of which I cannot be certain, the word is printed in {curly brackets}.

Copyright © 1974 Ram’s Horn Music. Renewed, 2002 Ram’s Horn Music. Additional lyrics, Copyright © 2018 Ram’s Horn Music. Courtesy of THE BOB DYLAN ARCHIVE® Collections, Tulsa, OK.